Thursday, December 16, 2021

Tomb of Three Freedmen

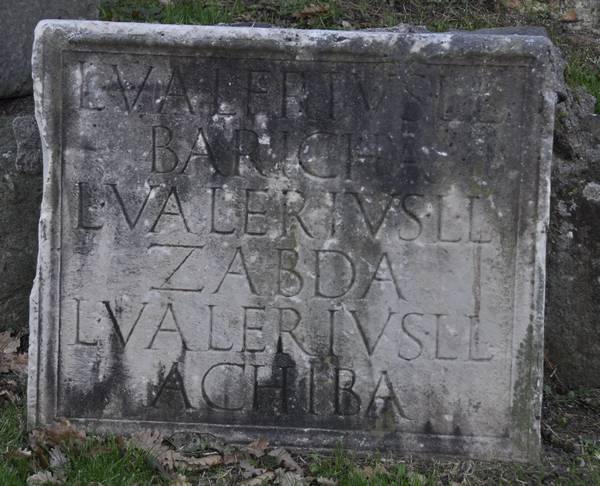

Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum VI 27959:

Newer› ‹Older

L(ucius) Valerius L(uci) l(ibertus) / Baricha / L(ucius) Valerius L(uci) l(ibertus) / Zabda / L(ucius) Valerius L(uci) l(ibertus) / AchibaRobert A. Kaster, The Appian Way: Ghost Road, Queen of Roads (2012; rpt. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014), pp. 43-44:

While some freedmen chose to be interred with their former masters, many arranged for tombs of their own. One of my favorite examples along the Appia is found near the fifth milestone, on the right side of the road as you’re heading away from town. There you will see the core of what used to be a substantial tower tomb, a tall pillar of conglomerate stone perhaps twenty-five feet high, set upon squared blocks of the volcanic tuff that’s plentiful in the area. At the base of the tower is a well-cut inscription on a block of the same stone. The inscription is in the usual all-capitals style, with the raised dots (“interpuncts”) used to separate words: the initial L in the first, third, and fifth lines stands for “Lucius,” a very common Roman first name, and the abbreviation L·L at the end of the same lines stands for “L(ucii) l(ibertus),” “the freedman of Lucius.” Three men, then, who were all once the slaves of a Lucius Valerius and took his name in the usual way, after they were freed. But it’s the names on the second, fourth, and sixth lines that rivet the attention: Baricha, Zabda, and Achiba. Plainly Semitic and probably Jewish, the names all but invite you to imagine a story about their owners, or at least to ask some questions. Were the three men brothers or fellow townsmen before they were taken in slavery? How were they taken? Were they captured when Titus, son of the emperor Vespasian and future emperor himself, sacked Jerusalem in 70 CE, part of the loot that we see soldiers hauling off in the scenes carved on Titus’s arch in the Forum? Or were they brought to Rome still earlier, on a slave dealer’s ship? (Inscriptions like this one are very hard to date: first century CE seems to be the consensus, but nothing can be said beyond that.) Were they among a number of Lucius Valerius’s freedmen buried in the same tomb? Or if so costly a tomb was theirs alone, how did they come to afford it? Had they been business partners in the years after slavery? In fact, might the Lucius Valerius Zabda recalled on this inscription be the same man as the Lucius Valerius Zabda mentioned on another first-century inscription from Rome — a former slave who became a slave dealer in his turn? But the mute stone, as spare and dignified in its own way as the marble plaque on Caecilia Metella’s tomb, provides no answers to satisfy modern curiosity.