Wednesday, December 31, 2014

Live for Today

Antiphon the Sophist, fragment 53a Diels (tr. Kathleen Freeman):

There are some who do not live the present life, but prepare with great diligence as if they were going to live another life, not the present one. Meanwhile time, being neglected, deserts them.

εἰσί τινες οἳ τὸν παρόντα μὲν βίον οὐ ζῶσιν, ἀλλὰ παρασκευάζονται πολλῆι σπουδῆι ὡς ἕτερόν τινα βίον βιωσόμενοι, οὐ τὸν παρόντα· καὶ ἐν τούτωι παραλειπόμενος ὁ χρόνος οἴχεται.

An Empty Bubble

Logan Pearsall Smith (1865-1946), Unforgotten Years (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1939), p. 278:

I shall not preach the ephemeral nothingness which Bossuet found beneath all hope and joy: the world may be an empty bubble, as the moralists tell us; but to me, as fear and hope, desire and belief, depart, the iridescence of that bubble grows lovelier every year.

To Loaf

Hal Borland (1900-1978), This Hill, This Valley (1957; rpt. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990), pp. 281-282:

I hear that the social planners are after us leisure-wasters again. We seem to be a menace to society. And our reformation depends entirely on our adopting hobbies. It's a sin to loaf. Not a mortal sin, maybe, but a sin against society. Besides, the social planners need something to do or they will have leisure to waste.James Russell Lowell (1819-1891), The Biglow Papers. Second Series (Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867), p. lvi:

I have tried to run down the etymology of the word loaf in the sense of taking it easy; but even the lexicographers seem unable to trace it. I have a hunch that it goes back to some language even earlier than Sanskrit, and I also have a hunch that the cryptographers who unravel the mysteries of ancient hieroglyphics will eventually find a clay tablet, perhaps from ancient Sumer, with a social planner's complaint about loafers. The planners and the loafers have been at it for a long, long time.

The heartening thing about it, to me, is that man continues to cherish his leisure and to insist on using it as he wishes. Also, I get great comfort from knowing that some of the best thoughts of all time have been generated by men who would be classified by the social planners as loafers and leisure-wasters. I'd as soon be a member of an ant colony as of a society in which a man didn't loaf now and then, just sit and think or, if he chose to, just sit.

To loaf: this, I think, is unquestionably German. Laufen is pronounced lofen in some parts of Germany, and I once heard one German student say to another, Ich lauf' (lofe) hier bis du wiederkehrest, and he began accordingly to saunter up and down, in short, to loaf.Oxford English Dictionary s.v. loaf v.2:

Etymology: Of obscure origin.Josef Bihl, "'Yokel' and 'Loaf'," Modern Language Review 23 (1928) 340:

Lowell's conjecture (adopted in recent Dicts.) that the verb is < German dialect lofen = laufen to run, is without foundation; the German verb has not the alleged sense 'to saunter up and down'. German landläufer (= land-loper n.) has a sense not very remote from that of loafer, but connection is not very probable.

N.E.D. is perhaps right in rejecting Lowell's conjecture that the word loaf is an adaptation of Ger. dial. lofen = laufen, but there can be little doubt that loaf, verb and noun, does go back to the German etymon lauf, the root being Teut. hlaup > Gothic hlaupan, A.S. hleapan, O.H.G. hlauffan. The German verb laufen not only means 'run,' but also 'saunter.' The nomen agentis, läufer, Suabian loafer, means 'a man who likes lounging about,' 'a vagrant.' N.E.D. quotes Leland to the effect that loaf, when it first began to be popular in 1834 or 1835, meant 'pilfer.' In this sense the word was already used by Luther. Mencken writes that an American authority said that loafer originated in a German mispronunciation of lover, i.e. as lofer. I should suggest an explanation just the other way round. There was a German dialect word lofer which became loafer in American. By the way, in the south of Germany, laufen sometimes means 'go to see one's sweetheart.' The only difficulty is whether American loaf, which, like yokel, was introduced into the United States by the German emigrants of the eighteenth century and afterwards migrated to England, is to be derived from the German verb or the nomen agentis. The sense of laufen (läufer) and loaf (loafer) is so much the same that connexion is not only probable but almost certain. The change of au, oa in Ger. dial. laufer, loafer into a long open English o is easy and natural: cp. Suabian loab (= standard German laib) and loaf.Related posts:

- Kayf

- Slackers

- Planet of the Apes

- Ode to Indolence

- The More Idle, the More Deserving

- Work and Leisure

- Praise of Laziness

- Lazy Man's Song

- Exquisite Pregnant Idleness

- How Can I Work?

- Dolce Far Niente

- Weekdays of Unfreedom

- The Dreary Vacuum of Idleness

- Idleness and Business

- Archilochus on the Idle Life

- Idleness

- Futile Work

- Otium Cum Dignitate

Tuesday, December 30, 2014

Life

Antiphon the Sophist, fragment 51 Diels (tr. Kathleen Freeman):

The whole of life is wonderfully open to complaint, my friend; it has nothing remarkable, great or noble, but all is petty, feeble, brief-lasting, and mingled with sorrows.

εὐκατηγόρητος πᾶς ὁ βίος θαυμαστῶς, ὦ μακάριε, [καὶ] οὐδὲν ἔχων περιττὸν οὐδὲ μέγα καὶ σεμνόν, ἀλλὰ πάντα σμικρὰ καὶ ἀσθενῆ καὶ ὀλιγοχρόνια καὶ ἀναμεμειγμένα λύπαις μεγάλαις.

Beatus Vir

Logan Pearsall Smith (1865-1946), Unforgotten Years (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1939), pp. 229-230:

What mortal is happier after all than the complacent, self-satisfied, self-applauding prig?

Research

Logan Pearsall Smith (1865-1946), Unforgotten Years (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1939), pp. 187-188:

This ideal of endowment for research was particularly shocking to Benjamin Jowett, the great inventor of the tutorial system which it threatened. I remember once, when staying with him at Malvern, inadvertently pronouncing the ill-omened word. "Research!" the Master exclaimed. "Research!" he said. "A mere excuse for idleness; it has never achieved, and will never achieve, any results of the slightest value." At this sweeping statement I protested, whereupon I was peremptorily told, if I knew of any such results of value, to name them without delay. My ideas on the subject were by no means profound, and anyhow it is difficult to give definite instances of a general proposition at a moment's notice. The only thing that came into my head was the recent discovery, of which I had read somewhere, that on striking a patient's kneecap sharply he would give an involuntary kick, and that by the vigor or lack of vigor of this "knee jerk," as it is called, a judgment could be formed of his general state of health.

"I don't believe a word of it," Jowett replied. "Just give my knee a tap."

I was extremely reluctant to perform this irreverent act upon his person, but the Master angrily insisted, and the undergraduate could do nothing but obey. The little leg reacted with a vigor which almost alarmed me, and must, I think, have considerably disconcerted that elderly and eminent opponent of research.

Monday, December 29, 2014

Gleaners

Ernest G. Sihler (1853-1942), From Maumee to Thames and Tiber: The Life-Story of an American Classical Scholar (New York City: The New York University Press, 1930), p. 215:

Jean-François Millet, Des glaneuses

There is a famous French canvas, "the Gleaners"—peasant women bending down to their humble work in the stubbly field. What, after all, are we, the classicists of these later times, but gleaners?

In Honor of Silvanus

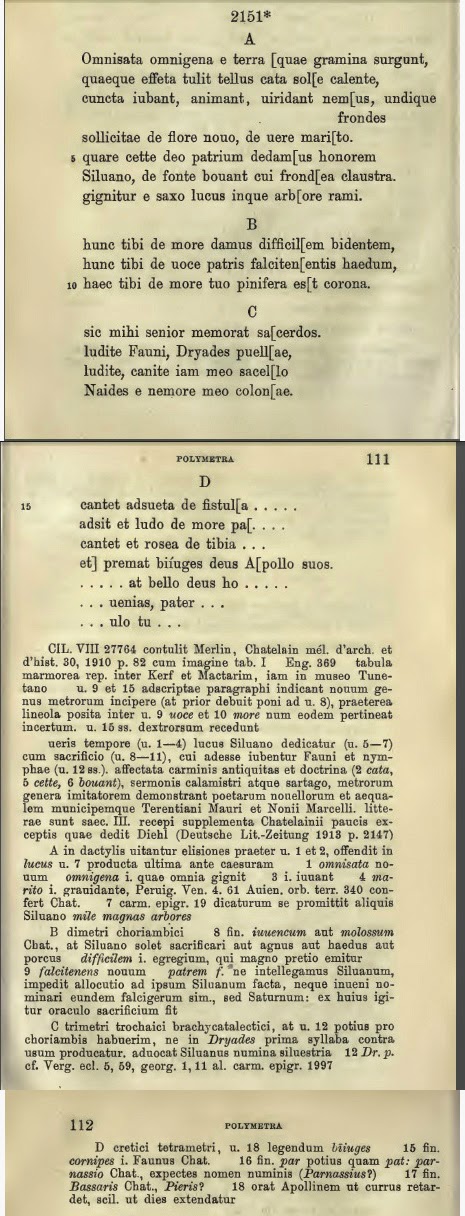

Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum 8.27764 = Carmina Latina Epigraphica 2151 (tr. E. Courtney):

Carmina Latina Epigraphica, III: Supplementum, ed. Ernest Lommatzsch (Leipzig: B.G. Teubner, 1926), pp. 110-112:

Bibliography:

Vegetation of all kinds which rises from the multi-planted earth, and the plants (?) which the ground, exhausted by the hot sun, has produced, all gladden, animate, give greenery to the grove; on all sides is foliage, anxious about the new flowers and about spring, its spouse. So, come along, let us give to the god Silvanus his ancestral honour; he has leafy bowers rustling from the spring, a grove growing from rock, and buds on the trees.Latin text (from Courtney):

According to custom we give you this intractable [ ], according to your sickle-bearing father's utterance we give you this (goat); according to custom you have this garland of pine.

The aged priest says this to me: 'Disport yourselves, Fauns, and, Dryad maidens, disport yourselves; Naiad dwellers, sing now from my temple out of my grove'.

Let [ ] make music from his usual pipe, and according to custom let Pan (?) attend the sport, and let [ ], rosy from playing the pipe, make music, and let divine Apollo halt his chariot. Let the god (Mars) cease from wild war, and you, father, come...

Omnisata omnigena e terra [quae gramina surguntCourtney tentatively translates his conjecture sata instead of the stonecutter's cata in line 2.

quaeque effeta tulit tellus cata sol[e calente,

cunta iubant, animant, uiridant nem[us; undique frondes

sollicitae de flore nouo, de uere mari[to.

quare cette deo patrium dedam[us honorem 5

Siluano, de fonte bouant cui frond[ea tecta,

gignitur e saxo lucus inque arb[ore gemmae.

hunc tibi de more damus difficil[em ˘¯x

hunc tibi de uoce patris falciten[entis haedum,

haec tibi de more tuo pinifera es[t corona. 10

sic mihi senior memorat sa[cerdos:

ludite Fauni Dryades puell[ae]

ludite, canite iam meo sacel[lo]

Naides e nemore meo colon[ae.]

cantet adsueta de fistul[a 15

adsit et ludo more pa.[

cantet et rosea de tibia [

et] premat biíuges deus A[pollo

desi]nat bello deus ho[rrido

tuque] uenias pater [ 20

Carmina Latina Epigraphica, III: Supplementum, ed. Ernest Lommatzsch (Leipzig: B.G. Teubner, 1926), pp. 110-112:

Bibliography:

- Louis Châtelain, "Le culte de Silvain en Afrique et l'inscription de la plaine du Sers (Tunisie)," Mélanges d'archéologie et d'histoire 30 (1910) 77-97

- G.B. Pighi, "Sul metro e sul significato di CIL VIII 27764 CE 2151," Epigraphica 5/6 (1943/1944) 40-44, rpt. in his Studi di Ritmica e Metrica (Torino: Bottega d'Erasmo, 1970), pp. 380-393 (non vidi)

- E. Courtney, Musa Lapidaria (Atlanta: Scholar's Press, 1995), pp. 144-147 (text and translation), 353-354 (commentary)

- Rocío Carande Herrero, "Huellas del estilo métrico" Habis 33 (2002) 599-614 (at 612-614)

Important Events of the 1950's

Eric Handley (1926-2013), "Lampada Tradam" (a speech delivered by Handley on the occasion of the celebration of his 80th birthday at Trinity College, Cambridge), p. 7:

The important event of the 1950's, apart from the ascent of Everest, the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, and the decipherment of the Linear B script by Michael Ventris, was the recovery, towards the end of the decade, of a lost play by Menander from a papyrus codex bought for the Bodmer library in Geneva.Hat tip: Alan Crease.

Sunday, December 28, 2014

The Function of a University

Alston Hurd Chase (1906-1994), letter to the editor of the Harvard Crimson (January 31, 1934), rpt. in his Time Remembered (San Antonio: Parker Publishing Inc., 1994), pp. 157-159:

I should be very grateful to you if you would allow me a perhaps inordinate amount of space in your columns to discuss what seem to me two great and lamentable fallacies in President Conant's report as you print it this morning. I make no apologies for so sharp a disagreement with Mr. Conant; his views and mine represent two completely hostile theories of the function of a university, and it seems to me that this is a proper moment for a clear definition of these divergent beliefs.

In the first place, Mr. Conant has more than once frankly expressed his conviction that a university is primarily a group of scholars dedicated to the pursuit and perpetuation of learning. I believe, on the contrary, that a university is an institution supported by society primarily for the purpose of educating young men and young women to take a useful and happy part in the life of their community, of their country, and of the world. Certainly this was the purpose in the mind of the great majority of those who have left endowments from their own property or who have voted special privileges and state support to the universities. The subordination of the educational function of a university to any other interest constitutes a betrayal of the implicit or explicit agreement contained in the acceptance of such aid. Such a betrayal is particularly regrettable today, when the fate of democratic institutions is in the balance, when the need for men trained not in factual minutiae but in the art of thought is greater than ever before.

Scholarship pure and unapplied is the game of a certain class, and such scholarship in a faculty is of no more ultimate importance than the powers of the university football team. By a process of diligent mystification, the learned classes have hood-winked society into believing that such scholarship is really important. With a good memory, a certain amount of industry, a talent for choosing obscure fields and perverse points of view one may become a famous scholar and console oneself in the polemics of the study for one's realized inferiority in other fields. There is no harm in such scholarship; it is a pleasant and, to a certain degree, a necessary thing, but to place it first among the functions of a university is, I repeat, a betrayal of the trust placed in us by society. It is to mistake a privilege for an inalienable right, exactly as the nobility and clergy of France forgot that their feudal privileges were merely payment for their services of protection and consolation and continued to demand those privileges long after they had ceased to do their duty. Society today is little tolerant of useless shibboleths. If we demand our privileges and refuse our duties we cannot expect so long a shrift as was granted the "ancien régime," and we can only hope that our fall may be, not less sudden, but less fatal.

I know that Mr. Conant insisted that scholarship and teaching ability should be combined, but the direction of his thought is clear from these words in which he explains that to be a good tutor or a good lecturer is not enough. When he does not say that it is not enough to be a good scholar, I find his silence eloquent.

The second fallacy in his position springs from his education as a scientist. Minute research is necessary in science, and is sometimes useful or, as in chemical warfare, fatal to society. In the field of the arts, however, this type of research is absolutely inappropriate. Most of the necessary cataloguing and indexing has been done. There will always remain, however, a place for books upon great authors and upon movements of profound importance. But such books are the fruit of a lifetime of patient and understanding contemplation, during which the scholar has become the very flesh and blood of his subject. The scientific method of minute research has only a subordinate place here, and calls for no great ability. Yet the arts have been striving for years to imitate the sciences and have filled Widener with their petty lucubrations upon dead themes. This is the second fallacy, to expect of the arts a type of scholarship proper only to science, to require this scholarship from young men, and thereby to discourage them in that leisurely, deep, and sincere study of their field which might bring forth works of real profit to mankind.

The scholarship which universities need is that which is born of a profound love of its subject, which is nourished by years of thought in the company of other minds, especially in classroom and conference, which is tested by teaching, and which is matured at last as a book which shall enable men to live with greater charity and nobility. Socrates, the greatest teacher men have known, said that no one knew a thing if he were unable to impart it to others. Countless lecture rooms bear ineloquent testimony to the ignorance of scholars.

At the risk of being found sentimental, I dare confess that I think that teaching is a mission. We are not here merely to create other puny scholars in our own image, but to send out into life men who shall, in the words of Pericles, be most completely and most gracefully self-sufficient in the face of the most varied circumstances. I know that I am not speaking for myself alone when I say that I had rather send forth one such man than be the lauded agent in dragging the poor bones of the dead from the oblivion to which they are committed by time's kindly hand.

Saturday, December 27, 2014

What's a Man Got Brains For?

Elias Canetti (1905-1994), Auto-da-Fé, Part II, Chapter I (tr. C.V. Wedgwood; Fischerle speaking):

A person who can't play chess, isn't a person. Chess is a matter of brain, I always say. A person may be twelve foot tall, but if he doesn't play chess, he's a fool. I play chess. I'm not a fool. Now I'm asking you; answer me if you like. If you don't, don't answer me. What's a man got brains for? I'll tell you, or you'll be worrying your head about it, wouldn't that be a shame? He's got brains to play chess with. Do you get me? Say yes, then that's that. Say no, I'll explain it all over again, for you.

Morning Walks of a Sinologist

Elias Canetti (1905-1994), Auto-da-Fé, Part I, Chapter I (tr. C.V. Wedgwood):

There is nothing else I can do, he said at last; he stepped aside into the porch of a house, looked round — nobody was watching him — and drew a long narrow notebook from his pocket. On the title page, in tall, angular letters was written the word: STUPIDITIES. His eyes rested at first on this. Then he turned over the pages; more than half the note-book was full. Everything he would have preferred to forget he put down in this book. Date, time and place came first. Then followed the incident which was supposed to illustrate the stupidity of mankind. An apt quotation, a new one for each occasion, formed the conclusion. He never read these collected examples of stupidity; a glance at the title page sufficed. Later on he thought of publishing them under the title 'Morning Walks of a Sinologist'.

Friday, December 26, 2014

Holidays

Gilbert K. Chesterton (1874-1936), Utopia of Usurers and Other Essays (New York: Boni and Liveright, 1917), pp. 31-32:

To anyone who knows any history it is wholly needless to say that holidays have been destroyed. As Mr. Belloc, who knows much more history than you or I, recently pointed out in the "Pall Mall Magazine," Shakespeare's title of "Twelfth Night: or What You Will" simply meant that a winter carnival for everybody went on wildly till the twelfth night after Christmas. Those of my readers who work for modern offices or factories might ask their employers for twelve days' holidays after Christmas. And they might let me know the reply.

Supreme Days in the Classicist's Life

Alston Hurd Chase (1906-1994), Time Remembered (San Antonio: Parker Publishing Inc., 1994), p. 96 (on Charles Burton Gulick):

I recall his telling us that there were two supreme days in the Classicist's life, that when he began to read Homer and that when he began to read Plato, each in the original Greek.

The Progress of American Education

Alston Hurd Chase (1906-1994), Time Remembered (San Antonio: Parker Publishing Inc., 1994), p. 3:

I must make one other comment upon my grandfather and his brothers. I recently found a number of their letters to their father and to one another. The orthography is faultless, the style, though slightly formal by modern standards, is natural and always clear. This provokes some musing upon the progress of American education, for these men had no schooling beyond that of a simple, one-room country schoolhouse, whereas vast numbers of today's graduates from our large and costly high schools are unable to write a simple declarative sentence or correctly maintain a checking account.

Thursday, December 25, 2014

Let Us All Be Merry

George Wither (1588-1667), "A Christmas Carroll," stanzas I-II:

So, now is come our joyfulst Feast;

Let ever man be jolly.

Each Roome, with Ivie leaves is drest,

And every Post, with Holly.

Though some Churles at our mirth repine,

Round your foreheads Garlands twine,

Drowne sorrow in a Cup of Wine.

And let us all be merry.

Now, all our Neighbours Chimneys smoke,

And Christmas blocks are burning;

Their Ovens, they with bakt-meats choke,

And all their Spits are turning.

Without the doore, let sorrow lie:

And, if for cold, it hap to die,

We'll bury 't in a Christmas Pie,

And evermore be merry.

The Dreaded Infant

John Milton (1608-1674), "On the Morning of Christ's Nativity," stanzas XIX-XXV:

XIX

The Oracles are dumm,

No voice or hideous humm

Runs through the arched roof in words deceiving. 175

Apollo from his shrine

Can no more divine,

With hollow shreik the steep of Delphos leaving.

No nightly trance, or breathed spell,

Inspire's the pale-ey'd Priest from the prophetic cell. 180

XX

The lonely mountains o're,

And the resounding shore,

A voice of weeping heard, and loud lament;

From haunted spring and dale

Edg'd with poplar pale, 185

The parting Genius is with sighing sent,

With flowre-inwov'n tresses torn

The Nimphs in twilight shade of tangled thickets mourn.

XXI

In consecrated Earth,

And on the holy Hearth, 190

The Lars, and Lemures moan with midnight plaint,

In Urns, and Altars round,

A drear, and dying sound

Affrights the Flamins at their service quaint;

And the chill Marble seems to sweat, 195

While each peculiar power forgoes his wonted seat.

XXII

Peor, and Baalim,

Forsake their Temples dim,

With that twise-batter'd god of Palestine,

And mooned Ashtaroth, 200

Heav'ns Queen and Mother both,

Now sits not girt with Tapers holy shine,

The Libyc Hammon shrinks his horn,

In vain the Tyrian Maids their wounded Thamuz mourn.

XXIII

And sullen Moloch fled, 205

Hath left in shadows dred.

His burning Idol all of blackest hue,

In vain with Cymbals ring,

They call the grisly king,

In dismall dance about the furnace blue; 210

The brutish gods of Nile as fast,

Isis and Orus, and the Dog Anubis hast.

XXIV

Nor is Osiris seen

In Memphian Grove, or Green,

Trampling the unshowr'd Grasse with lowings loud: 215

Nor can he be at rest

Within his sacred chest,

Naught but profoundest Hell can be his shroud:

In vain with Timbrel'd Anthems dark

The sable-stoled Sorcerers bear his worshipt Ark. 220

XXV

He feels from Juda's land

The dredded Infants hand,

The rayes of Bethlehem blind his dusky eyn;

Nor all the gods beside,

Longer dare abide, 225

Nor Typhon huge ending in snaky twine:

Our Babe, to shew his Godhead true,

Can in his swadling bands controul the damned crew.

Greek and Latin

Gabriel Setoun, pseudonym of Thomas Nicoll Hepburn (1861–1930), Robert Urquhart (New York: R.F. Fenno & Company, 1896), p. 33:

"Is he no college-bred after a'?" he asked.

"Ou, he's college-bred richt enough."

Michael felt relieved.

"He'll be able to read Greek an' Latin then, like his mother-tongue."

"Greek an' Latin!" Watty joined in the conversation, hurling out the words with a vehemence that startled his friends. "Ye say the words as if they were sacred, makin' to yoursel's gods o' godless languages. An' what's your M.A.'s an' your B.A.'s after a', but empty shibboleths, that no mair distinguish the learned frae the onlearned, than the names their fathers ga'e them. Gold's stampet because it is gold, no because it has come through the meltin' pat."

Wednesday, December 24, 2014

The Same Fate

Homer, Iliad 9.318-320 (tr. Samuel Butler):

He that fights fares no better than he that does not; coward and hero are held in equal honour, and death deals like measure to him who works and him who is idle.The same, tr. Richmond Lattimore:

Fate is the same for the man who holds back, the same if he fights hard.The same, tr. Alexander Pope:

We are all held in a single honour, the brave with the weaklings.

A man dies still if he has done nothing, as one who has done much.

Fight or not fight, a like reward we claim,The Greek:

The wretch and hero find their prize the same.

Alike regretted in the dust he lies,

Who yields ignobly, or who bravely dies.

ἴση μοῖρα μένοντι καὶ εἰ μάλα τις πολεμίζοι·

ἐν δὲ ἰῇ τιμῇ ἠμὲν κακὸς ἠδὲ καὶ ἐσθλός·

κάτθαν᾽ ὁμῶς ὅ τ᾽ ἀεργὸς ἀνὴρ ὅ τε πολλὰ ἐοργώς.

More Hexameters Consisting of Words in Asyndeton

Greek Anthology 5.51 (tr. W.R. Paton):

Greek Anthology 5.135 (an address to a wine-jar; tr. W.R. Paton):

For similar examples in Latin and Greek see:

I fell in love, I kissed, I was favoured, I enjoyed, I am loved; but who am I, and who is she, and how it befel, Cypris alone knows.The first line, a hexameter, consists entirely of a series of verbs in asyndeton.

ἠράσθην, ἐφίλουν, ἔτυχον, κατέπραξ᾿, ἀγαπῶμαι·

τίς δέ, καὶ ἧς, καὶ πῶς, ἡ θεὸς οἶδε μόνη.

Greek Anthology 5.135 (an address to a wine-jar; tr. W.R. Paton):

Round, well-moulded, one-eared, long-necked, babbling with thy little mouth, merry waitress of Bacchus and the Muses and Cytherea, sweetly-laughing treasuress of our club, why when I am sober are you full and when I get tipsy do you become sober? You don't keep the laws of conviviality.The first line, a hexameter, consists entirely of a series of vocative adjectives in asyndeton.

στρογγύλη, εὐτόρνευτε, μονούατε, μακροτράχηλε,

ὑψαύχην, στεινῷ φθεγγομένη στόματι,

Βάκχου καὶ Μουσέων ἱλαρὴ λάτρι καὶ Κυθερείης,

ἡδύγελως, τερπνὴ συμβολικῶν ταμίη,

τίφθ᾽ ὁπόταν νήφω, μεθύεις σύ μοι, ἢν δὲ μεθυσθῶ,

ἐκνήφεις; ἀδικεῖς συμποτικὴν φιλίην.

For similar examples in Latin and Greek see:

- Some Lines in Lucretius

- Asyndeton Filling Hexameters

- Asyndeton Filling Hexameters in Sidonius

- Verse-Filling Asyndeton

- Verse-Filling Asyndeton: Some Greek Examples

- Another Greek Example of Verse-Filling Asyndeton

- More Examples of Asyndeton Filling Hexameters

- Asyndeton Filling Hexameters in Corippus

- Twelve Gods

- Seven Cities

- A Hexameter Consisting of Nouns in Asyndeton

Tuesday, December 23, 2014

A Particular Dialogue

Ronald A. Knox (1888-1957), "A Particular Dialogue," The Salopian (July 1918), rpt. In Three Tongues, ed. L.E. Eyres (London: Chapman & Hall, 1959), pp. 133-134:

If you put your ear to the chink under the door of the Upper Sixth on the night before June the 21st, you can hear the Greek particles talking on the floor. Each of them must chip in once, and none more than once, for fear of being scratched out; so it is rather like a debating society. This is what I heard when I listened.Hat tip: Ian Jackson.

'Well, as I was saying', began Mentoinun, 'I don't see any use in continuing to exist, when we make no real difference to the prose we live in.'

'Yes, but' interposed Allaoun 'you must confess that we make some difference; the prose would be poorer without us'.

'Well, what about it?' said Timeen, 'I don't see the point of enriching, by our presence, these vulgar nouns and bloated verbs'.

'Be that as it may' said Deoun 'I think in their heart of hearts they do recognize our value'.

'And what's more', added Kaideekai in a great hurry, 'they're coming to recognize it more and more every day'.

'As a matter of fact', said Kaigar, 'I hear they're quite likely to pass a vote of thanks to us'.

'More likely to crush us out of existence', grunted Menoun.

'You don't mean to say', cried Oumeenge, 'that we're faced with an Asyndeton?'

'Suppose, if you like', said Kaidee, 'that they did crush us out of existence, we should still have been, and our memory would still be a sort of protest against sheer materialism'.

'I suppose we should all admit', said Deepou meditatively, 'that posterity will recognize its debt to us'.

'Not but what', suggested Oumeenalla a little doubtfully, 'I think a little asyndeton would be good for some of us'.

'Of course', added Menpou, 'we are not of any great practical value'.

'And proud not to be, I hope', said Kaige.

At this moment, by the merest ill luck, I coughed behind the door.

'Hush' said Kaimeen 'there's somebody coming'.

Monday, December 22, 2014

Assumptions

E.B. White (1889-1985), "Coon Tree," The Points of my Compass (New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1962), pp. 61-75 (at 68-69):

Many of the commonest assumptions, it seems to me, are arbitrary ones: that the new is better than the old, the untried superior to the tried, the complex more advantageous than the simple, the fast quicker than the slow, the big greater than the small, and the world as remodeled by Man the Architect functionally sounder and more agreeable than the world as it was before he changed everything to suit his vogues and his conniptions.

A Child of Nature

Bradford Torrey (1843-1912), "December Out-of-Doors," The Foot-Path Way (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1892), pp. 36-66 (at 40):

It was good, I thought, to see so many people out-of-doors. Most of them had employment in the shops, probably, and on grounds of simple economy, so called, would have been wiser to have stuck to their lasts. But man, after all that civilization has done for him (and against him), remains at heart a child of nature. His ancestors may have been shoemakers for fifty generations, but none the less he feels an impulse now and then to quit his bench and go hunting, though it be only for a mess of clams.

Heresy

Derwas J. Chitty (1901-1971), The Desert a City: An Introduction to the Study of Egyptian and Palestinian Monasticism under the Christian Empire (1966; rpt. Crestwood: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, n.d.), p. 56 (on Epiphanius):

For him, anything he could not understand must surely be heresy.

Saturday, December 20, 2014

Where Shall We Hear Better Preaching?

Bradford Torrey (1843-1912), "In Praise of the Weymouth Pine," The Foot-Path Way (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1892), pp. 232-242 (at 232-233):

Ivan Shishkin, Forest Reserve, Pine Grove

I could never think it surprising that the ancients worshiped trees; that groves were believed to be the dwelling places of the gods; that Xerxes delighted in the great plane-tree of Lydia; that he decked it with golden ornaments and appointed for it a sentry, one of "the immortal ten thousand." Feelings of this kind are natural; among natural men they seem to have been well-nigh universal. The wonder is that any should be without them. For myself, I cannot recollect the day when I did not regard the Weymouth pine (the white pine I was taught to call it, but now, for reasons of my own, I prefer the English name) with something like reverence. Especially was this true of one,—a tree of stupendous girth and height, under which I played, and up which I climbed till my cap seemed almost to rub against the sky. That pine ought to be standing yet; I would go far to lie in its shadow. But alas! no village Xerxes concerned himself for its safety, and long, long ago it was brought to earth, it and all its fair lesser companions. There is no wisdom in the grave, and it is nothing to them now that I remember them so kindly. Some of them went to the making of boxes, I suppose, some to the kindling of kitchen fires. In like noble spirit did the illustrious Bobo, for the love of roast pig, burn down his father's house.Id. (at 237-239):

The solitary pine, unhindered, symmetrical, green to its lowermost twig, as it rises out of the meadow or stands a-tiptoe on the rocky ledge, is a thing of beauty, a pleasure to every eye. A pity and a shame that it should not be more common! But the pine forest, dark, spacious, slumberous, musical! Here is something better than beauty, dearer than pleasure. When we enter this cathedral, unless we enter it unworthily, we speak not of such things. Every tree may be imperfect, with half its branches dead for want of room or want of sun, but until the devotee turns critic—an easy step, alas, for half-hearted worshipers—we are conscious of no lack. Magnificence can do without prettiness, and a touch of solemnity is better than any amusement.

Where shall we hear better preaching, more searching comment upon life and death, than in this same cathedral? Verily, the pine is a priest of the true religion. It speaks never of itself, never its own words. Silent it stands till the Spirit breathes upon it. Then all its innumerable leaves awake and speak as they are moved. Then "he that hath ears to hear, let him hear." Wonderful is human speech,—the work of generations upon generations, each striving to express itself, its feelings, its thoughts, its needs, its sufferings, its joys, its inexpressible desires. Wonderful is human speech, for its complexity, its delicacy, its power. But the pine-tree, under the visitations of the heavenly influence, utters things incommunicable; it whispers to us of things we have never said and never can say,—things that lie deeper than words, deeper than thought. Blessed are our ears if we hear, for the message is not to be understood by every corner, nor, indeed, by any, except at happy moments. In this temple all hearing is given by inspiration, for which reason the pine-tree's language is inarticulate, as Jesus spake in parables.

Capitalism

G.K. Chesterton (1874-1936), Utopia of Usurers and Other Essays (New York: Boni and Liveright, 1917), p. 81:

By all the working and orthodox standards of sanity, Capitalism is insane. I should not say to Mr. Rockefeller "I am a rebel." I should say "I am a respectable man and you are not."

Reaction to the Higher Criticism

Thomas Hardy (1840-1928), "The Respectable Burgher on 'The Higher Criticism'":

Since Reverend Doctors now declare

That clerks and people must prepare

To doubt if Adam ever were;

To hold the flood a local scare;

To argue, though the stolid stare,

That everything had happened ere

The prophets to its happening sware;

That David was no giant-slayer,

Nor one to call a God-obeyer

In certain details we could spare,

But rather was a debonair

Shrewd bandit, skilled as banjo-player:

That Solomon sang the fleshly Fair,

And gave the Church no thought whate'er;

That Esther with her royal wear,

And Mordecai, the son of Jair,

And Joshua's triumphs, Job's despair,

And Balaam's ass's bitter blare;

Nebuchadnezzar's furnace-flare,

And Daniel and the den affair,

And other stories rich and rare,

Were writ to make old doctrine wear

Something of a romantic air:

That the Nain widow's only heir,

And Lazarus with cadaverous glare

(As done in oils by Piombo's care)

Did not return from Sheol's lair:

That Jael set a fiendish snare,

That Pontius Pilate acted square,

That never a sword cut Malchus' ear

And (but for shame I must forbear)

That ——— did not reappear! ...

—Since thus they hint, nor turn a hair,

All churchgoing will I forswear,

And sit on Sundays in my chair,

And read that moderate man Voltaire.

Thursday, December 18, 2014

Some Remnant of the Primitive Man

John Burroughs (1837-1921), Winter Sunshine (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1904), p. 23:

How one lingers about a fire under such circumstances, loath to leave it, poking up the sticks, throwing in the burnt ends, adding another branch and yet another, and looking back as he turns to go to catch one more glimpse of the smoke going up through the trees! I reckon it is some remnant of the primitive man, which we all carry about with us. He has not yet forgotten his wild, free life, his arboreal habitations, and the sweet-bitter times he had in those long-gone ages. With me, he wakes up directly at the smell of smoke, of burning branches in the open air; and all his old love of fire and his dependence upon it, in the camp or the cave, come freshly to mind.

The Golden Mean

Greek Anthology 5.37 (by Rufinus; tr. W.R. Paton):

I briefly considered λεπτὸν for λεῖπον in the last line, but it was a bad idea—λεῖπον (present participle of λείπω) balances πλέον perfectly and reprises λείπει in the preceding line.

Take not to your arms a woman who is too slender nor one too stout, but choose the mean between the two. The first has not enough abundance of flesh, and the second has too much. Choose neither deficiency nor excess.Denys Page in his commentary calls this "the feeblest of Rufinus' epigrams."

μήτ᾿ ἰσχνὴν λίην περιλάμβανε μήτε παχεῖαν,

τούτων δ᾿ ἀμφοτέρων τὴν μεσότητα θέλε.

τῇ μὲν γὰρ λείπει σαρκῶν χύσις, ἡ δὲ περισσὴν

κέκτηται· λεῖπον μὴ θέλε μηδὲ πλέον.

I briefly considered λεπτὸν for λεῖπον in the last line, but it was a bad idea—λεῖπον (present participle of λείπω) balances πλέον perfectly and reprises λείπει in the preceding line.

Not Worth Doing?

T.R. Glover (1869-1943), The Influence of Christ in the Ancient World (1929; rpt. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), p. 21:

Many things have been done by later men, which the man of Periclean Athens could not have done, but a large proportion of these things they might not have thought worth the doing.

Wednesday, December 17, 2014

Turtles

E.B. White (1899-1985), "Turtle Blood Bank," Writings from the New Yorker 1927-1976 (New York: HarperPerennial, 1991), pp. 12-13:

Medical men, it seems, are interested in turtle blood, because turtles don't suffer from arteriosclerosis in old age. The doctors are wondering whether there is some special property of turtle blood that prevents the arteries from hardening. It could be, of course. But there is also the possibility that a turtle's blood vessels stay in nice shape because of the way turtles conduct their lives. Turtles rarely pass up a chance to lay in the sun on a partly submerged log. No two turtles ever lunched together with the idea of promoting anything. No turtle ever went around complaining that there is no profit in book publishing except from the subsidiary rights. Turtles do not work day and night to perfect explosive devices that wipe out Pacific islands and eventually render turtles sterile. Turtles never use the word "implementation" or the phrases "hard core" and "in the last analysis." No turtle ever rang another turtle back on the phone. In the last analysis, a turtle, although lacking knowledge, knows how to live. A turtle, by its admirable habits, gets to the hard core of life. That may be why its arteries are so soft.Related post: Lessons from Animals.

Tuesday, December 16, 2014

Paradise

The Cynic's Breviary: Maxims and Anecdotes from Nicolas de Chamfort. Selected and Translated by William G. Hutchinson (London: Elkin Mathews, 1902), p. 50:

Duclos was speaking one day of the paradise that everyone imagines for himself in his own way. "Here are the ingredients for yours, Duclos," said Madame de Rochefort; "Wine, bread, and cheese, and the first woman who might come on the scene."In French:

Duclos parlait un jour du paradis, que chacun se fait à sa manière. Madame de Rochefort lui dit: «Pour vous, Duclos, voici de quoi composer le vôtre: du pain, du vin, du fromage et la première venue.»

He Can Endure No Noise

Ben Jonson (1572-1637), Epicoene, or The Silent Woman, Act I, Scene 1:

TRUEWIT. I met that stiffe peece of Formalitie, his Vncle, yesterday, with a huge Turbant of Night-Caps on his head, buckled over his eares.Id.:

CLERIMONT. O, that's his custome when he walkes abroad. Hee can endure no noyse, man.

TRUEWIT. How do's he for the Bells?Related posts:

CLERIMONT. O, i' the Queenes time, he was woont to goe out of Towne euery Saturday at ten a clocke, or on Holy-day-eues. But now, by reason of the sicknesse, the perpetuitie of ringing has made him deuise a roome, with double walles, and treble seelings; the windores close shut, and calk'd: and there he liues by Candle-light. Hee turn'd away a man last weeke, for hauing a paire of new Shooes, that creak'd.

Amber and Spice

Anne Wilkinson (1910-1961), "Amber and Spice," from "Notes on Robert Burton's 'The Anatomy of Melancholy'," in The First Five Years: A Selection from The Tamarack Review, ed. Robert Weaver (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1962), pp. 58-62 (at 58):

If the brain be cool and moist,A friend suggested to me that Wilkinson's notes could use their own notes. The source of this poem is Burton's Anatomy of Melancholy, Part. II, Sect. IV, Mem. I, Subs. IV:

Amber and spice, amber and spice.

But should the brain be hot and dry

Amber and spice will your wits away.

Amber and Spice will make a hot brain mad, good for cold and moist.

Monday, December 15, 2014

Epitaph of Quintus Aelius Apollonius

Année Épigraphique 1947, 31 (tr. E. Courtney):

Some bibliography:

To a man is given life that is slippery, shaky, fleeting, fragile, good or bad, treacherous, hanging on a slender thread through a variety of chances with no clearly-marked finishing-post. Live to the full, mortal, while the Fates grant you time, whether the country embraces you or cities or a military camp or the sea. Love the flowers of Venus, pluck the benign gifts of Ceres and the generous gifts of Bacchus and the viscous gifts of Athena; cultivate a serene life, calm because of your clear conscience. Speedily a boy and a youth, speedily a man and then worn out by old age, you will be like this in the tomb, with no memory of the honours of men alive on earth.The epitaph is an acrostic (Lupus fecit). The gifts of Ceres, Bacchus, and Athena (lines 6-7) are bread, wine, and olive oil.

Lubrica quassa levis fragilis bona vel mala fallax

Vita data est homini, non certo limite cretae,

Per varios casus tenuato stamine pende(n)s.

Vivito, mortalis, dum dant tibi tempora Parc(a)e,

Seu te rura tenent, urbes seu castra vel (a)equor. 5

Flores ama Veneris, Cereris bona munera carpe

Et Nysii larga et pinguia dona Minervae;

Candida(m) vita(m) cole iustissima mente serenus.

Iam puer et iu(v)enis, iam vir et fessus ab annis,

Talis eris tumulo superumque oblitus honores. 10

Some bibliography:

- Wolfgang Schmid, "Contritio und 'Ultima Linea Rerum' in neuen epikureischen Texten," Rheinisches Museum für Philologie 100(1957) 301-327 (at 315-327)

- Wilhelm Seelbach, "Zu lateinischen Dichtern (Catull c. 4, Horaz c. I 28, Lupus von Aquincum)," Rheinisches Museum für Philologie 106 (1963) 348-351 (at 350-351)

- E. Courtney, Musa Lapidaria (Atlanta: Scholar's Press, 1995), pp. 186-187 (text and translation), 398-399 (commentary)

- Paolo Cugusi, "Carmina Latina Epigraphica e novellismo: Cultura di centro e cultura di provincial contenuti e metodologia di ricerca," Materiali e discussioni per l'analisi dei testi classici 53 (2004) 125-172 (at 156-158)

- Werner Eck, "Tod in Raphia: Kulturtransfer aus Pannonien nach Syria Palaestina," Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 184 (2013) 117–125, rpt. in his Judäa - Syria Palästina (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2014), pp. 284-295

Sunday, December 14, 2014

The History of Nonsense

Saul Lieberman, quoted in Benjamin Isaac, The Invention of Racism in Classical Antiquity (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004), p. 150, n. 376:

Nonsense is nonsense, but the history of nonsense is scholarship.Sometimes attributed to others.

A Hexameter Consisting of Nouns in Asyndeton

Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum 5.7781 = Inscriptiones Latinae Selectae 735 = Carmina Latina Epigraphica 893, line 5:

cives tecta forum portus commercia portasIf portus is construed as accusative plural (with E. Courtney, Musa Lapidaria, p. 258) rather than as genitive singular depending on commercia (with F. Bücheler, Anthologia Latina sive Poesis Latinae Supplementum, Pars Posterior, Fasciculus II, p. 413), then this is a hexameter consisting entirely of nouns in asyndeton. For other examples in Latin and Greek see:

- Some Lines in Lucretius

- Asyndeton Filling Hexameters

- Asyndeton Filling Hexameters in Sidonius

- Verse-Filling Asyndeton

- Verse-Filling Asyndeton: Some Greek Examples

- Another Greek Example of Verse-Filling Asyndeton

- More Examples of Asyndeton Filling Hexameters

- Asyndeton Filling Hexameters in Corippus

- Twelve Gods

- Seven Cities

Saturday, December 13, 2014

Samuel Johnson's Last Words

Dear Mike,

The dying words of 'blinking Sam' Johnson were uttered 230 years ago today, St. Lucy's Day, but what were they? On the premise that biographers and pious witnesses are either shameless ventriloquists or wilfully embellish and reorder events for their own purposes, I opt for the most banal of the three versions recorded. 'Iam moriturus' would have to have been shouted from bedroom to dining-room by a patient in severe respiratory distress*, and as last words, 'God bless you' have a conventional piety about them that arouse suspicion, although they may well have been spoken that day. The third version, John Hoole's — 'he said something upon its [a cup of warm milk] not being properly given into his hand' — is made doubly insipid as dying reported speech. Presumably, Frank or someone else attending Johnson, had put the cup directly to his lips and so 'encumber[ed] him with help'. And perhaps the dying man, momentarily irked, had struggled to marshal his ebbing strength to grasp the cup himself, as he had done countless times daily for decades with his beloved cups of tea. The metaphor of 'holding onto life' has its corollary in this last simple act of will on the part of a man helplessly bedridden. Exactly what the speech-act consisted of we will never know, but it brings into focus Johnson's quintessential humanity no less than any studied utterances of blessing or foreboding.

* see Mary Jane Hurst, "Samuel Johnson's Dying Words," English Language Notes 23 (1985) 45-53

Best wishes,

Eric [Thomson]

The dying words of 'blinking Sam' Johnson were uttered 230 years ago today, St. Lucy's Day, but what were they? On the premise that biographers and pious witnesses are either shameless ventriloquists or wilfully embellish and reorder events for their own purposes, I opt for the most banal of the three versions recorded. 'Iam moriturus' would have to have been shouted from bedroom to dining-room by a patient in severe respiratory distress*, and as last words, 'God bless you' have a conventional piety about them that arouse suspicion, although they may well have been spoken that day. The third version, John Hoole's — 'he said something upon its [a cup of warm milk] not being properly given into his hand' — is made doubly insipid as dying reported speech. Presumably, Frank or someone else attending Johnson, had put the cup directly to his lips and so 'encumber[ed] him with help'. And perhaps the dying man, momentarily irked, had struggled to marshal his ebbing strength to grasp the cup himself, as he had done countless times daily for decades with his beloved cups of tea. The metaphor of 'holding onto life' has its corollary in this last simple act of will on the part of a man helplessly bedridden. Exactly what the speech-act consisted of we will never know, but it brings into focus Johnson's quintessential humanity no less than any studied utterances of blessing or foreboding.

* see Mary Jane Hurst, "Samuel Johnson's Dying Words," English Language Notes 23 (1985) 45-53

Best wishes,

Eric [Thomson]

Books as Sedatives

Frederic Harrison (1831-1923), The Choice of Books and Other Literary Pieces (1885; rpt. London: Macmillan and Co., Limited, 1899), pp. 88-89:

Now I suppose, at the bottom of all this lies that rattle and restlessness of life which belongs to the industrial Maelström wherein we ever revolve. And connected therewith comes also that literary dandyism, which results from the pursuit of letters without any social purpose or any systematic faith. To read from the pricking of some cerebral itch rather than from a desire of forming judgments; to get, like an Alpine club stripling, to the top of some unsealed pinnacle of culture; to use books as a sedative, as a means of exciting a mild intellectual titillation, instead of as a means of elevating the nature; to dribble on in a perpetual literary gossip, in order to avoid the effort of bracing the mind to think—such is our habit in an age of utterly chaotic education. We read, as the bereaved poet made rhymes—

"For the unquiet heart and brain,We, to whom steam and electricity have given almost everything excepting bigger brains and hearts, who have a new invention ready for every meeting of the Royal Institution, who want new things to talk about faster than children want new toys to break, we cannot take up the books we have seen about us since our childhood: Milton, or Molière, or Scott. It feels like donning knee-breeches and buckles, to read what everybody has read, what everybody can read, and which our very fathers thought good entertainment scores of years ago. Hard-worked men and over-wrought women crave an occupation which shall free them from their thoughts and yet not take them from their world. And thus it comes that we need at least a thousand new books every season, whilst we have rarely a spare hour left for the greatest of all.

A use in measured language lies;

The sad mechanic exercise,

Like dull narcotics, numbing pain."

A Priamel by Asclepiades

Greek Anthology 5.169 (by Asclepiades; tr. Kenneth Rexroth):

It is sweet in summer to slakeThe same, tr. W.R. Paton:

Your thirst with snow, and the spring breeze

Is sweet to the sailors after

The stormy winter, but sweetest

Of all when one blanket hides two

Lovers at the worship of Kypris.

Sweet in summer a draught of snow to him who thirsts, and sweet for sailors after winter's storms to feel the Zephyr of the spring. But sweeter still when one cloak doth cover two lovers and Cypris hath honour from both.The same, tr. J.W. Mackail:

Sweet is snow in summer for one athirst to drink, and sweet for sailors after winter to see the Crown of spring; but most sweet when one cloak hides two lovers, and the praise of Love is told by both.The Greek:

ἡδὺ θέρους διψῶντι χιὼν ποτόν, ἡδὺ δὲ ναύταις

ἐκ χειμῶνος ἰδεῖν εἰαρινὸν Στέφανον·

ἥδιον δ᾽ ὁπόταν κρύψῃ μία τοὺς φιλέοντας

χλαῖνα, καὶ αἰνῆται Κύπρις ὑπ᾽ ἀμφοτέρων.

2 Στέφανον codd.: Ζέφυρον Alph. Hecker, Commentationis Criticae de Anthologia Graeca Pars Prior (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1852), p. 213

Friday, December 12, 2014

If You Want to Know Everything

Ausonius 6.5.2 (my translation):

If you want to know everything, read the Odyssey from start to finish.Out of context, I realize, but I like the idea.

perlege Odyssean omnia nosse volens.

Make Haste and Read All These Things

Charles James Fox, letter to Richard Fitzpatrick (September 22, 1767):

For God's sake learn Italian as fast as you can, if it be only to read Ariosto. There is more good poetry in Italian than in all other languages that I understand put together. In prose, too, it is a very fine language. Make haste and read all these things, that you may be fit to talk to Christians.

Know-It-Alls

Plautus, Trinummus 199-211 (tr. Paul Nixon):

There's certainly nothing more silly and stupid, more subdolous and voluble, more brassymouthed and perjured than these city busybodies called men about town. Yes, and I put myself in the very same category with 'em, swallowing as I did the falsehoods of fellows that affect to know everything and don't know anything. Why, what each man has in mind, or will have, they know; know what the king whispers to the queen; know what Juno chats about with Jove. Things that don't exist and never will—still they know 'em all. Not a straw do they care whether their praise or blame, scattered where they please, is fair or unfair, so long as they know what they like to know.Id. 217-222:

nihil est profecto stultius neque stolidius

neque mendaciloquius neque argutum magis, 200

neque confidentiloquius neque peiurius,

quam urbani assidui cives, quos scurras vocant.

atque egomet me adeo cum illis una ibidem traho,

qui illorum verbis falsis acceptor fui,

qui omnia se simulant scire neque quicquam sciunt. 205

quod quisque in animo habet aut habiturust sciunt,

sciunt id quod in aurem rex reginae dixerit,

sciunt quod Iuno fabulatast cum Iove;

quae neque futura neque sunt, tamen illi sciunt.

falson an vero laudent, culpent quem velint, 210

non flocci faciunt, dum illud quod lubeat sciant.

Ah, if we only went to the root of everything they hear and tell about, and demanded their authority, and then fined and punished our tittletattlers if they didn't produce it—if we did this, we'd be doing a public service, and I warrant there'd be few people knowing what they don't know, and quite a lull in their blitherblather.There is a lesson here for journalists, bloggers, talk show hosts, and the like.

quod si exquiratur usque ab stirpe auctoritas,

unde quidquid auditum dicant, nisi id appareat,

famigeratori res sit cum damno et malo,

hoc ita si fiat, publico fiat bono, 220

pauci sint faxim qui sciant quod nesciunt,

occlusioremque habeant stultiloquentiam.

Thursday, December 11, 2014

Persistence in Unrequited Love

Terence, The Mother-in-Law 343-344 (tr. John Barsby):

To love someone who's taken a dislike to you is stupid twice over, if you ask me: you're wasting your own time and you're causing annoyance to the other person.

nam qui amat quoi odio ipsus est, bis facere stulte duco:

laborem inanem ipsus capit et illi molestiam affert.

Monastic Tippling

Benediktinermönch mit Wein beim Frühschoppen

Sarah Foot, Monastic Life in Anglo-Saxon England c. 600-900 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), pp. 238-239:

Conviviality could, however. be taken to extremes and there were concerns in various quarters about the excesses of English religious and clergy, particularly in their consumption of alcohol. Bede complained about the behaviour of episcopal communities in his letter to Ecgberht, bishop of York:

It is rumoured abroad about certain bishops that they serve Christ in such a fashion that they have with them no men of any religion or continence, but rather those who are given to laughter, jests, tales, feasting and drunkenness, and the other attractions of a lax life. and who daily feed the stomach with feasts more than the soul on the heavenly sacrifice.280The vice of drunkenness particularly disturbed Boniface, who writing to Archbishop Cuthbert lamented 'it is said that the vice of drunkenness is far too common in your parochiae and that some bishops not only do not prohibit it. but themselves drink to the point of intoxication'. He thought this habit peculiar to the heathen and the English: 'neither the Franks, nor the Gauls, nor the Lombards, nor the Romans, nor the Greeks practise it', he claimed.281 Writing to a bishop of Lindisfarne, Alcuin recommended him to surround himself with 'such men as are always learning and who rejoice more in learning than in being drunk'.282 His most famous and outspoken statement on the subject came in a letter to 'Speratus', long identified with Bishop Higbald of Lindisfarne but shown by Bullough in fact to have been addressed to Unuuona (bishop of Leicester 781x785-801x803). Alcuin urged the bishop to pay more attention to his performance in church than to the pomp of his banquets:

What kind of praise is it that your table is loaded so high that it can hardly be lifted and yet Christ is starving at the door? ... It is better that the poor should eat at your table than entertainers and persons of extravagant behaviour. Avoid those who engage in heavy drinking, as blessed Jerome says, 'like the pit of Hell' ... Splendour in dress and the continual pursuit of drunkenness are insanity ... May you be the example of all sobriety and self-control.An indication of the extent of the problem in the early English church is provided by the first chapter of the penitential canons attributed to Archbishop Theodore, which was concerned with 'excess and drunkenness'. Bishops and ordained clergy could be removed from office for persistent drunkenness.284 A brother who drank to the point of vomiting was to do penance for thirty days, but if he drank to excess because he had previously been abstinent for some time or because he had been celebrating a saint's day or one of the greater festivals such as Christmas or Easter (and if he had drunk no more than his seniors had recommended him), then he was to be let off the penance.285 At Clofesho in 747, monks and clerics were advised to avoid the vice of drunkenness as a deadly poison, and also recommended to ensure that they did not allow others to drink intemperately, but rather to have wholesome and sober entertainments lest they bring disrepute on the habit that symbolised their religious status.286 Yet, in other contexts, both Alcuin and Boniface could be more relaxed about the dangers of alcoholic drink. While visiting York, Alcuin wrote to Joseph, an Irish pupil of his on the continent, complaining that his hosts were running out of wine and the bitter beer was playing havoc with his stomach, but he hoped that Uinter, medicus, was soon going to send him two cartloads of best clear wine from Francia.287 Boniface sent two small casks of wine to Ecgberht of York, 'so that you may have a merry day with the brethren'.288 Whatever the difficulties its provision might cause, it is clear that alcohol was drunk in Anglo-Saxon minsters throughout our period even if certain notably holy men and women chose to be abstinent.289 Some houses may have been able to make their own wine: there were a number of vineyards in southern England in 1066 and at least one minster, Glastonbury, is known to have owned one in the tenth century.290

280 Bede, EpEcg, ch. 4 (p. 407).

281 Boniface, Ep. 78 (pp. 170-1). The force of that last remark is somewhat weakened by the charge of drunkenness Boniface had laid on the Frankish episcopate in an earlier letter to Pope Zacharias: Ep. 50 (p. 83).

282 Alcuin, Ep. 285 (p. 444). Compare Epp. 20, 21, 230, 290 (pp. 58, 58-9, 374, 448). See Donald Bullough, Friends, Neighbours and Fellow-Drinkers: Aspects of Community and Conflict in the Early Medieval West (Cambridge: Department of Anglo-Saxon, Norse and Celtic, 1991), pp. 9-10.

283 Alcuin, Ep. 124 (p. 183); translated by Donald Bullough, 'What has Ingrid to do with Lindisfarne?', Anglo-Saxon England 22 (1993), 93-125, at p. 124.

284 Theodore, Penitential, I.i.1 (ed. Finsterwalder, p. 288). Bullough, Friends, Neighbours and Fellow-Drinkers, p. 10, n. 18; Campbell, 'Elements in the background', p. 12.

285 Theodore, Penitential, I.i.2; I.i.4 (p. 289).

286 Council of Clofesho, AD 747, ch. 21 (H&S III, 369).

287 Alcuin, Ep. 8 (p. 33).

288 Boniface, Ep. 91 (p. 208).

289 Cuthbert was said to have abstained from all intoxicants: Bede. VSCuth. ch. 6 (pp. 174-5). See further Magennis, Images of Community, pp. 57-9.

290 S 626 (AD 956).

Wednesday, December 10, 2014

Cool Out of a Cellar a Mile Deep

Dear Mike,

Brecht's Pleasures (the book or the bathing or both) put me in mind of this brief vita-beatior reverie from one of Keats' letters. Also a short poem by classicist Luis Alberto de la Cuenca inspired by the passage (translation mine).

Hyder Edward Rollins, ed., The Letters of John Keats, Vol. II: 1819-1821 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1958, rpt. 2011), p. 56 (1 May(?) 1819):

Best wishes,

Eric [Thomson]

Brecht's Pleasures (the book or the bathing or both) put me in mind of this brief vita-beatior reverie from one of Keats' letters. Also a short poem by classicist Luis Alberto de la Cuenca inspired by the passage (translation mine).

Hyder Edward Rollins, ed., The Letters of John Keats, Vol. II: 1819-1821 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1958, rpt. 2011), p. 56 (1 May(?) 1819):

O there is nothing like fine weather, and health, and Books, and a fine country, and a contented Mind, and a Diligent habit of reading and thinking, and an amulet against ennui—and, please heaven, a little claret-wine cool out of a cellar a mile deep—with a few or a good many ratafia cakes—a rocky basin to bathe in, a strawberry bed to say your prayers to Flora in, a pad nag to go you ten miles or so; two or th[r]ee sensible people to chat with; two or three spiteful folkes to spar with; two or three odd fishes to laugh at and two or three numskuls to argue with—instead of using dumb bells on a rainy day...Luis Alberto de Cuenca (b. 1950), Por fuertes y fronteras (Visor, 1996), p. 65:

Sobre una Carta de John KeatsAs a topos, isn't 'Haec sunt' a sanguine cousin of and antidote to 'Ubi sunt'?

Un dios por quien jurar. El buen tiempo (supongo).

La salud. Muchos libros. Un paisaje de Friedrich.

La mente en paz. Tu cuerpo desnudo en la terraza.

Un macizo de lilas donde rezar a Flora.

Dos o tres enemigos y dos o tres amigos.

Todo eso junto es la felicdad.

On a Letter by John Keats

A god to swear by. Fine weather (I suppose).

Health. Plenty of books. A Friedrich landscape.

A contented mind. Your unclothed body on the terrace.

A clump of lilacs for the worship of Flora.

Two or three enemies and two or three friends.

All that together is happiness.

Best wishes,

Eric [Thomson]

Tuesday, December 09, 2014

Pleasures

Bertolt Brecht (1898-1956), "Pleasures," in Poems. Part Three 1938-1956 (London: Methuen, 1976), p. 448 (I don't have the book and don't know who did the translation):

The first look out of the window in the morningThe German ("Vergnügungen"), from his Gesammelte Werke, Bd. 10 (Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp, 1967), p. 1022:

The old book found again

Enthusiastic faces

Snow, the change of the seasons

The newspaper

The dog

Dialectics

Taking showers, swimming

Old music

Comfortable shoes

Taking things in

New music

Writing, planting

Travelling

Singing

Being friendly.

Der erste Blick aus dem Fenster am MorgenHat tip: Alan Crease.

Das wiedergefundene alte Buch

Begeisterte Gesichter

Schnee, der Wechsel der Jahreszeiten

Die Zeitung

Der Hund

Die Dialektik

Duschen, Schwimmen

Alte Musik

Bequeme Schuhe

Begreifen

Neue Musik

Schreiben, Pflanzen

Reisen

Singen

Freundlich sein.

Health Tip

Pliny the Elder, Natural History 28.17.62 (tr. W.H.S. Jones):

Moreover to refrain from talking is healthful for many reasons.

iam et sermoni parci multis de causis salutare est.

Cider

Vivian Rowe, Return to Normandy (London: Evans Brothers Limited, 1951), p. 52:

Every traveller, every guide book, will tell you that cider is the drink of Normandy, that when in Rome you should do as the Romans, that you should always drink the drink of the country you are in. In a sense, cider is the drink of Normandy, but there is never traveller or guide-book to tell you when it is to be drunk. Certainly it is not to be drunk with fine dishes; honest wine is cheap all over France, and Normandy is no exception to that rule, even though the vine does not flourish there.Related post: Cider.

No, cider is to be drunk when you are thirsty, after a long walk or ride along a dusty road. Its pleasant sharpness drives away thirst, its deceptively imperceptible strength overcomes fatigue, the natural virtue of the fruit restores the elasticity of tired muscles. It is a splendid refresher between meals, but makes a deplorable mésalliance with delicate foods. It is sold in two forms, corked (bouché) or uncorked; the only difference I have ever been able to find between the two, save for a slight variation in price in favour of the latter, is that the uncorked has its sediment at top and bottom, and the corked, if any, at the bottom only.

You will meet, as I have done, the Englishman who turns up his nose at Norman cider as thin sour stuff not worth the trouble of drinking, then you will know that he has been brought up on the fabricated, gassy stuff, all but tasteless and non-alcoholic, which all too often goes by the name of cider in England and which appeals to palates of those who have never passed beyond a teen-age appreciation of sugared and aerated liquids prepared by commercial laboratories. Be tactful with him, for he errs from ignorance. Do not laugh him to scorn or hold him up to contempt, but rather lead him quietly to a more mature appreciation. By doing so, you will probably add years to his life and greatly increase the pleasure he derives from it.

Monday, December 08, 2014

Dumb and Dumbest

Plautus, Bacchides 1087-1089 (tr. Wolfgang de Melo):

All the weakheads, thickheads, fatheads, mushrooms, idiots, drongos, cretins, wherever they are, were, or will be hereafter, all these I alone surpass by far in idiocy and stupid habits.I need a dictionary for the English as much as for the Latin. What is a drongo? Oxford English Dictionary, s.v., sense 3:

quiquomque ubi sunt, qui fuerunt quique futuri sunt posthac

stulti, stolidi, fatui, fungi, bardi, blenni, buccones,

solus ego omnis longe antideo

stultitia et moribus indoctis.

A simpleton, a stupid person; see also quot. 1942. Hence as adj., silly, foolish. Austral. slang....1942 A.G. Mitchell in Southerly Apr., Drongo, an R.A.A.F. recruit.

The Greatest of All Earthly Calamities

John Forster, Walter Savage Landor: A Biography (London: Chapman and Hall, 1874), p. 142:

Hat tip: Eric Thomson.

The letter of January 1809, in which he told Southey that he had a private bill coming up before parliament, replied likewise to an invitation from his friend to the Lakes [....] 'I wish I had settled in your country. I could live without Bath. As to London, its bricks and tiles and trades and fogs make it odious and intolerable. I am about to do what no man has ever done in England, plant a wood of cedar of Lebanon. These trees will look magnificent on the mountains of Llananthony unmixt with others; and perhaps there is not a spot on the earth where eight or ten thousand are to be seen together.'Id., p. 143:

He had matters greatly troubling him at the same date. Though hardly yet in complete possession of the abbey [Llananthony], his 'uninterrupted series of vexations and disappointments in connection with it' had already begun. Not only his Welsh neighbours had been doing him some mischief, but one of his own servants had cut down about sixty fine trees, lopping others; and this, which he considered as the greatest of all earthly calamities, as he told Southey in a letter from Bath, had confined him to the house for several days. 'We recover from illness, we build palaces, we retain or change the features of the earth at pleasure—excepting that only! The whole of human life can never replace one bough.'Malcolm Elwin, Savage Landor (New York: MacMillan, 1941) p. 385:

They [Thomas De Quincey's daughters] "found him delightful company," and related of him a characteristic Boythornism. When he remarked on some trees in the garden, their aunt replied that they were now less beautiful than they had been, having been recently lopped.Among Landor's last works are Last Fruit off an Old Tree (1853) and Dry Sticks, fagoted by Walter Savage Landor (1858).

On this Mr. Landor immediately said "Ah! I would not lop a tree; if I had to cut a branch, I would cut it down to the ground. If I needed to have my finger cut off, I would cut off my whole arm!" lifting up that member decisively as he spoke.

Hat tip: Eric Thomson.

Labels: arboricide

Sunday, December 07, 2014

She is a Happy Ship

[Warning: The following is probably of no interest to anyone except my family.]

My expatriate grandfather died in Shanghai in January, 1941. Had he lived longer, he might have shared the fate of his Russian-born wife (my step-grandmother), who was afterwards imprisoned in a Japanese internment camp. There were seven such civilian internment camps in Shanghai, and I don't know in which one she was confined. Included in a prisoner exchange, she sailed from Shanghai to Mormugao, Goa, aboard the Teia Maru (departed September 20, arrived October 15, 1943). An exchange of Japanese and allied civilian prisoners took place at Mormugao. She then sailed from Mormugao to New York aboard the Gripsholm (departed October 22, arrived December 1, 1943), after which I can find no trace of her.

Here is the route taken by the ships Teia Maru and Gripsholm, from The Shanghai Evening Post, American Edition (Dec. 3, 1943), p. 1:

Here is a photograph of the Teia Maru:

Here is a photograph of the Gripsholm:

The prisoner exchange was a prominent news story during late 1943. See e.g.

My expatriate grandfather died in Shanghai in January, 1941. Had he lived longer, he might have shared the fate of his Russian-born wife (my step-grandmother), who was afterwards imprisoned in a Japanese internment camp. There were seven such civilian internment camps in Shanghai, and I don't know in which one she was confined. Included in a prisoner exchange, she sailed from Shanghai to Mormugao, Goa, aboard the Teia Maru (departed September 20, arrived October 15, 1943). An exchange of Japanese and allied civilian prisoners took place at Mormugao. She then sailed from Mormugao to New York aboard the Gripsholm (departed October 22, arrived December 1, 1943), after which I can find no trace of her.

Here is the route taken by the ships Teia Maru and Gripsholm, from The Shanghai Evening Post, American Edition (Dec. 3, 1943), p. 1:

Here is a photograph of the Teia Maru:

Here is a photograph of the Gripsholm:

The prisoner exchange was a prominent news story during late 1943. See e.g.

- Shelly Smith Mydans, "Letter from Mormugao," Life Magazine (November 29, 1943) 11-12, 14

- Carl and Shelly Mydans, "Tomorrow We Will Be Free," Life Magazine (December 6, 1943) 106-108, 111-114

- "Americans Return", Life Magazine (December 20, 1943) 87-93

Ritus

John Scheid, "Graeco Ritu: A Typically Roman Way of Honoring the Gods," Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 97 (1995) 15-31 (at 17-18):

To our way of thinking, a ritual is a religious—or at least public—celebration. As a traditional set of gestures and behavior, it is currently opposed and subordinated to the interior and spiritual approach to the divine. I shall not go into details, but this definition of ritual and consequently of ritus is a construction of modern times whose origin reaches back, let us say, to the Reformation. Anyway, this was not the precise meaning of ritus. This did not define the content of a divine service, but only the general custom, the rule followed in celebrating this service. Ritus is not equivalent to sacra, caerimoniae, or religiones, but to mos, the way of doing something, the τρόπος or the νόμος. You have the mos of birds, of horses, of human beings or of Romans, Albans, Greeks, barbarians, and so on. In the religious field, the difference did not lie in the content of the celebration itself, but in the way of celebrating the ceremonies, whatever they were. The meaning of ritus is to be referred to the notion which the ancients had of religion. There was not a true and a false religion. National religion was not radically different from foreign religions. Even the religions of the barbarians were not substantially different from the religions of civilised people. Everywhere people made sacrifices, prayers, and vows, celebrated sacred games, and built sanctuaries. The same terminology was used for the description of all these celebrations, not to mention the net of interpretation which connected the gods of the oikoumene. But one thing made the difference between the religions of the world: the governing rules, those small details, choices, and postures which gave each system its originality, on occasion its perversion. Some individuals or people were qualified as superstitious, not because they venerated the wrong gods or celebrated ridiculous ceremonies, but because they performed their cult in the wrong way; this means for example that they did it in an excessively fearful way, an attitude which did not accord with the dignitas of a god or a citizen. The Celts of Gaul were classed as barbarians, not because they adored idols or celebrated sacrifices, but because their rules did not restrain them from sacrificing human victims: the ritus of these barbarians consisted in offering human beings, not in the other proceedings of the sacrifice. In short, the ritus was the special posture and prescription which gave all public celebrations a special, recognizable tonality—I would compare it to the musical modes: you had the ritus of the Romans, the ritus of the Greeks, the ritus of the barbarians, and so on.

Saturday, December 06, 2014

An Economy of Time

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882), Society and Solitude. Twelve Chapters (Boston: Fields, Osgood & Co., 1870), p. 175:

'Tis therefore an economy of time to read old and famed books. Nothing can be preserved which is not good; and I know beforehand that Pindar, Martial, Terence, Galen, Kepler, Galileo, Bacon, Erasmus, More, will be superior to the average intellect. In contemporaries, it is not so easy to distinguish betwixt notoriety and fame.Cf. his Journals (September, 1838):

Be sure, then, to read no mean books. Shun the spawn of the press on the gossip of the hour.

It is always an economy of time to read old and famed books. Time is a sure sifter. Nothing can be preserved that is not good, and I know beforehand that Martial, Plautus, Terence, Pliny, Polybius; or Galen, Kepler, Galileo, Spinoza, Hobbes, Bacon, Hooker, Erasmus, More, etc. will be superior to the average intellect. In contemporary merits, it is not always possible to distinguish betwixt notoriety and fame.

In Very Small Doses

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882), Society and Solitude. Twelve Chapters (Boston: Fields, Osgood & Co., 1870), p. 12:

But the people are to be taken in very small doses. If solitude is proud, so is society vulgar.

Res Pro Rei Defectu: Some Examples

E. Courtney, Musa Lapidaria (Atlanta: Scholar's Press, 1995), pp. 227-228 (on Carmina Latina Epigraphica 9, line 3: quoiei uita defecit, non | honos, honore(m)):

Courtney, op. cit., p. 305 (on Carmina Latina Epigraphica 949, line 5: quod spes eripuit, spes certe redd[i]t amanti):

Related post: Res Pro Rei Defectu.

We therefore have an elaborate pun, 'whose life-span, not (lack of) respect, denied him office'; honos is an instance of the idiom res pro rei defectu (Madvig on Cic. De Fin. 2.73; C.F.W. Müller in Friedländer's note on Juv. 2.39, Kühner-Gerth, Gr. Gramm., Satzlehre 2.569-70), cf. on 91.5; τιμή at Eur. Hipp. 1402 signifies 'lack of honour'.I can't find anything on this idiom in Madvig's commentary on Cicero, De Finibus 2.73. I've quoted Müller on Juvenal 2.39 here.

Courtney, op. cit., p. 305 (on Carmina Latina Epigraphica 949, line 5: quod spes eripuit, spes certe redd[i]t amanti):

In 5 the first spes means 'lack of hope'...These meanings of honor and spes aren't recognized in the Oxford Latin Dictionary or in Lewis and Short, s.vv. Likewise in Liddell-Scott-Jones, s.v. τιμή, there is no citation of Euripides, Hippolytus 1402 τιμῆς ἐμέμφθη, where W.S. Barrett in his commentary translates "found fault with, was dissatisfied, over the (lack of) honour paid to her".

Related post: Res Pro Rei Defectu.

Labels: auto-antonyms

Friday, December 05, 2014

A Roadside Café

Elizabeth David (1913-1992), French Provincial Cooking (1960; rpt. New York: Penguin Books, 1999), pp. 151-152:

I vividly remember, for instance, the occasion when, having stopped for petrol at a filling station at Remoulins near the Pont du Gard, we decided to go into the café attached to it, and have a glass of wine. It was only eleven o'clock in the morning but for some reason we were very hungry. The place was empty, but we asked if we could have some bread, butter and sausage. Seeing that we were English, the old lady in charge tried to give us a ham sandwich, and when we politely but firmly declined this treat she went in search of the patron to ask what she should give us.

He was an intelligent and alert young man who understood at once what we wanted. In a few minutes he reappeared and set before us a big rectangular platter in the centre of which were thick slices of home-made pork and liver pâté, and on either side fine slices of the local raw ham and sausage; these were flanked with black olives, green olives, freshly washed radishes still retaining some of their green leaves, and butter.