Monday, October 31, 2022

Epitaph of Quintus Caelius and Camidia Aphrodisia

Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum X 5371 = Carmina Latina Epigraphica 118 = Inscriptiones Latinae Selectae 7734 (lnteramna, Republican era):

On the epitaph see Alfredo Mario Morelli, "Di alcuni carmi epigrafici in senari giambici nel Latium Adiectum," in Heikki Solin, ed., Le Epigrafi della Valle di Comino. Atti del quattordicesimo convegno epigrafico cominese. Atina - Palazzo Ducale, 27-28 maggio 2017 ([San Donato Val di Comino]: Associazione "Genesi", 2018), pp. 111-121, and Gregory Bucher, "We all die, so have a drink while you can," Συγγράμματα (February 18, 2022).

There is a complete misunderstanding of the epitaph in Judson Allen Tolman Jr., A Study of the Sepulchral Inscriptions in Buecheler's Carmina Epigraphica Latina (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1910), p. 96:

Vivit Q(uintus) Caelius Sp(uri) f(ilius) Vivi(us) architectus navalis, vivit uxor Camidia M(arci) l(iberta) Aprhodisia.Photograph of the stone: There is a translation of the inscription in Brian K. Harvey, Roman Lives: Ancient Roman Life as Illustrated by Latin Inscriptions, corr. ed. (Indianapolis: Focus Publishing, 2015), p. 172 (with his notes):

Hospes resiste et nisi molestust, perlege.

noli stomachare. suadeo, caldum bibas.

moriundust. vale.

He lives: Quintus Caelius Vivius(?), son of Spurius,1 naval architect.2 She lives: his wife, Camidia Aphrodisia, freedwoman of Marcus. Friend, stop and read unless it is annoying (to stop). Do not be irritated. I ask that you drink a hot beverage. It is the kind of thing that passes away.3 Goodbye.But caldum isn't just "a hot beverage," but rather vinum cum aqua calida mixtum, i.e. wine mixed with hot water — see Ernst Diehl, Vulgärlateinische Inschriften (Bonn: A. Marcus und E. Weber, 1910), p. 56 (inscription number 633). And moriundust is "we must die", rather than "it is the kind of thing that passes away". On -ust for -umst or -um est see Manu Leumann, Lateinische Laut- und Formenlehre (Munich: C.H. Beck, 1977), p. 123 (§ 134, 2).

1 Vivius was freeborn, but he married a freedwoman.

2 Vivius designed and built ships.

3 It was quite common on tombstones to encourage the reader to enjoy life in some particular way which the deceased enjoyed, because life was seen as fleeting.

On the epitaph see Alfredo Mario Morelli, "Di alcuni carmi epigrafici in senari giambici nel Latium Adiectum," in Heikki Solin, ed., Le Epigrafi della Valle di Comino. Atti del quattordicesimo convegno epigrafico cominese. Atina - Palazzo Ducale, 27-28 maggio 2017 ([San Donato Val di Comino]: Associazione "Genesi", 2018), pp. 111-121, and Gregory Bucher, "We all die, so have a drink while you can," Συγγράμματα (February 18, 2022).

There is a complete misunderstanding of the epitaph in Judson Allen Tolman Jr., A Study of the Sepulchral Inscriptions in Buecheler's Carmina Epigraphica Latina (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1910), p. 96:

Inscription 118 is peculiar. The reader is advised to drink cold water if reading the monument makes him angry.

Destructible

Aëtius, Placita 2.4.7 (tr. Jaap Mansfeld and David T. Runia):

Anaximander Anaximenes Anaxagoras Archelaus Diogenes Leucippus (say that) the cosmos is destructible.

Ἀναξίμανδρος Ἀναξιμένης Ἀναξαγόρας Ἀρχέλαος Διογένης Λεύκιππος φθαρτὸν τὸν κόσμον.

We Go On Looking

Gustaf Sobin (1935-2005), Luminous Debris: Reflecting on Vestige in Provence and Languedoc (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), p. 17:

We read on. We go on looking, as we've always looked, not so much for them as for ourselves, our own, obscure traces. Reading books, visiting museums, or simply stopping short before the vast, gold umbrella of some chestnut tree in mid-autumn, aren't we always, in a sense, looking for ourselves? A lonely species by nature, made even more so today by the loss of any commonly shared vision—any collectively accepted referent—we wander through galleries, archival tumuli, and archeological vestige, hoping to discover, at any given instant, the key, the tiny, metallic glint in the midst of our own shadows. Call it, if you will, the breath at the very heart of our own empty mirror.

Taphophilia

A grave yard in Ireland:

Hat tip: A friend, who writes:

I'm beginning to realize how much of my time is spent in grave yards on excursions. And you seem to have taken seriously to epitaphs on the blog. An unhealthy preoccupation, my mother would say.

Giving Credit Where It's Due

Apuleius, Florida 18.32-35 (on Thales; tr. H.E. Butler):

Even when he was far advanced into the vale of years, he evolved a divinely inspired theory concerning the period of the sun's revolution through the circle in which he moves in all his majesty. This theory, I may say, I have not only learned from books, but have also proved its truth by experiment. This theory Thales is said to have taught soon after its discovery to Mandrolytus of Priene. The latter, fascinated by the strangeness and novelty of his newly acquired knowledge, bade Thales choose whatever recompense he might desire in return for such precious instruction. 'It is enough recompense,' replied Thales the wise, 'if you will refrain from claiming as your own the theory I have taught you, whenever you begin to impart it to others, and will proclaim me and no other as the discoverer of this new law.' In truth that was a noble recompense, worthy of so great a man and beyond the reach of time. For that recompense has been paid to Thales down to this very day, and shall be paid to all eternity by all of us who have realized the truth of his discoveries concerning the heavens.Benjamin Todd Lee on 18.32 (with a typographical error corrected):

idem sane iam proclivi senectute divinam rationem de sole commentus est, quam equidem non didici modo, verum etiam experiundo comprobavi, quoties sol magnitudine sua circulum quem permeat metiatur. id a se recens inventum Thales memoratur edocuisse Mandrolytum Priennensem, qui nova et inopinata cognitione impendio delectatus optare iussit, quantam vellet mercedem sibi pro tanto documento rependi. 'satis,' inquit, 'mihi fuerit mercedis,' Thales sapiens, 'si id quod a me didicisti, cum proferre ad quospiam coeperis, non tibi adsciveris, sed eius inventi me potius quam alium repertorem praedicaris.' pulchra merces prorsum ac tali viro digna et perpetua; nam et in hodiernum ac dein semper Thali ea merces persolvetur ab omnibus nobis, qui eius caelestia studia vere cognovimus.

Lit. "how many times in respect to its own size the sun measures the orbit that it travels." This calculation related the sun's diameter to its apparent orbit, a ratio of 1:720. For this calculation cf. Diels Vorsokratiker I2 p3; Vallette 165n1 with Diogenes Laertius 1.24; for more cf. A. Wasserstein, "Thales' determination of the diameters of the sun and the moon," JHS 75 (1955), 214-216.I have seen this several times, in the corporate world and elsewhere — people taking undeserved credit for work that others have done. It always strikes me as especially low and despicable behavior, an odious blend of falsehood and theft.

Sunday, October 30, 2022

Epitaph of Titus Cissonius

Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum III 6825 = Carmina Latina Epigraphica 243, from Antioch in Pisidia, 1st century AD, tr. William C. McDermott, "Milites Gregarii,"

Greece & Rome 17.2 (October, 1970) 184-196 (at 188):

Titus Cissonius, son of Quintus, of the Sergian tribe, a veteran of the fifth Gallic legion. (He says):McDermott adds disapprovingly:

"While I lived, I drank freely; you who are alive, drink".

Publius Cissonius, son of Quintus, of the Sergian tribe, his brother, constructed (this tomb).

T(itus) Cissonius Q(uinti) f(ilius) Ser(gia) vet(eranus) leg(ionis) V Gall(icae).

dum vixi, bibi libenter; bibite vos qui vivitis.

P(ublius) Cissonius Q(uinti) f(ilius) Ser(gia) frater fecit.

Parallels are not far to seek: Petronius (35) and a myriad pseudo-sophisticated pseudo-Epicureans from every generation. Titus Cissonius and his brother Publius are exemplars of a universal, timeless frivolity.Photograph (not a very good one) of the stone:

Honor Thy Mother

"The Instruction of Any," tr. Miriam Lichtheim, Ancient Egyptian Literature, Vol. II: The New Kingdom (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973), pp. 135-146 (at 141):

Double the food your mother gave you,Hat tip: Mrs. Laudator.

Support her as she supported you;

She had a heavy load in you,

But she did not abandon you.

When you were born after your months,

She was yet yoked (to you),

Her breast in your mouth for three years.

As you grew and your excrement disgusted,

She was not disgusted, saying: "What shall I do!"

When she sent you to school,

And you were taught to write,

She kept watching over you daily,

With bread (8, 1) and beer in her house.

Saturday, October 29, 2022

Civilization

G.K. Chesteron, The Napoleon of Notting Hill (London: John Lane, The Bodley Head, 1904), p. 42:

"Many clever men like you have trusted to civilisation. Many clever Babylonians, many clever Egyptians, many clever men at the end of Rome. Can you tell me, in a world that is flagrant with the failures of civilisation, what there is particularly immortal about yours?"

An Oracle

Dio Cassius 57.18.4-5 (tr. Earnest Cary):

They were furthermore disturbed not a little by an oracle, reputed to be an utterance of the Sibyl, which, although it did not fit this period of the city's history at all, was nevertheless applied to the situation then existing. It ran:"When thrice three hundred revolving years have run their course,λόγιόν τέ τι ὡς καὶ Σιβύλλειον, ἄλλως μὲν οὐδὲν τῷ τῆς πόλεως χρόνῳ προσῆκον, πρὸς δὲ τὰ παρόντα ᾀδόμενον, οὐχ ἡσυχῇ σφας ἐκίνει· ἔλεγε γὰρ ὅτι·

Civil strife upon Rome destruction shall bring, and the folly, too,

Of Sybaris . . ."τρὶς δὲ τριηκοσίων περιτελλομένων ἐνιαυτῶν

Ῥωμαίους ἔμφυλος ὀλεῖ στάσις, χἁ Συβαρῖτις

ἀφροσύνα.

A Saying Attributed to Thales

Diogenes Laertius 1.33 (tr. R.D. Hicks):

Hermippus in his Lives refers to Thales the story which is told by some of Socrates, namely, that he used to say that there were three blessings for which he was grateful to Fortune: "first, that I was born a human being and not one of the brutes; next, that I was born a man and not a woman; thirdly, a Greek and not a barbarian."Plutarch, Life of Marius 46.1 (tr. Bernadotte Perrin):

Ἕρμιππος δ' ἐν τοῖς Βίοις εἰς τοῦτον ἀναφέρει τὸ λεγόμενον ὑπό τινων περὶ Σωκράτους. ἔφασκε γάρ, φασί, τριῶν τούτων ἕνεκα χάριν ἔχειν τῇ Τύχῃ· πρῶτον μὲν ὅτι ἄνθρωπος ἐγενόμην καὶ οὐ θηρίον, εἶτα ὅτι ἀνὴρ καὶ οὐ γυνή, τρίτον ὅτι Ἕλλην καὶ οὐ βάρβαρος.

Plato, however, when he was now at the point of death, lauded his guardian genius and Fortune because, to begin with, he had been born a man and not an irrational animal; again, because he was a Greek and not a Barbarian; and still again, because his birth had fallen in the times of Socrates.Lactantius, Divine Institutes 3.19.17 (tr. Mary Francis McDonald):

Πλάτων μὲν οὖν ἤδη πρὸς τῷ τελευτᾶν γενόμενος ὕμνει τὸν αὐτοῦ δαίμονα καὶ τὴν τύχην, ὅτι πρῶτον μὲν ἄνθρωπος, εἶτα Ἕλλην, οὐ βάρβαρος οὐδὲ ἄλογον τῇ φύσει θηρίον γένοιτο, πρὸς δὲ τούτοις, ὅτι τοῖς Σωκράτους χρόνοις ἀπήντησεν ἡ γένεσις αὐτοῦ.

That theory of Plato's is not dissimilar, because he said that he was thankful to nature, first, because he was born a man rather than a dumb beast; then, because he was a man rather than a woman, a Greek rather than a foreigner; and, finally, because he was an Athenian and of the time of Socrates.Related post: Distinctions.

non dissimile Piatonis illud est, quod aiebat 'se gratias agere naturae: primum quod homo natus esset potius quam mutum animal, deinde quod mas potius quam femina, quod Graecus quam barbarus, postremo quod Atheniensis et quod temporibus Socratis.'

Friday, October 28, 2022

The Bomford Cup

Attic black-figure drinking cup, ca. 520 BC, at Oxford, Ashmolean Museum (inv. no. 1974.344):

I don't have access to John Boardman,

"A Curious Eye Cup," Archäologischer Anzeiger (1976) 281–290. See Beth Cohen, The Colors of Clay: Special Techniques in Athenian Vases (Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2006), pp. 258-259, from which I borrowed the photographs.

Rebel

G.K. Chesterton, "Tennyson," Varied Types (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1915), pp. 249-257 (at 252):

He is only a very shallow critic who cannot see an eternal rebel in the heart of the Conservative.

A Bereaved Family

Reinhold Merkelbach and Josef Stauber, Steinepigramme aus dem griechischen Osten, Bd. 2: Die Nordküste Kleinasiens (Marmarasee und Pontos) (Munich: K.G. Saur, 2001), pp. 123-124 (08/08/12, from Hadrianoi pros Olympon; click once or twice to enlarge):

The Greek, followed by my translation:

[ π]αίδων ἀώρ[ων ]There is a Latin translation of the epitaph in Ed. Cougny, Epigrammatum Anthologia Palatina cum Planudeis et Appendice Nova Epigrammatum Veterum ex Libris et Marmoribus, Vol. III (Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1890), pp. 187-188 (number 589, reading στονάχησει with Le Bas and Waddington in line 10):

[καὶ θ]ρῆνος γονέων ἀπαρήγορον ἐνθάδ' [ἀθρ]ήσας·

γνῶθι τέλος βιότου· διὸ παῖζε τρυφῶν ἐπὶ κόσμῳ,

πρὶν σῶν παίδων πένθος τοῖον ἀθρῆσαι ἐπὶ τύμβοις·

τίς ἡμετέρων γονέων παρήγορος ἔσται ἐνὶ οἴκῳ 5

ἢ θρῆνος παύσει πολυώδυνον ἐν βιότοιο;

τίνα χερσὶν πατὴρ ἢ περιπτύξεται ἢ τίνα κλαύσει;

Μηνόφιλον θρηνεῖ· Τερτύλλαν παρήγορον ἕξει;

ἢ Μαιάδιν τὸν ἄριστον; πλείω πένθος ὤπασε τούτοις·

πάνγεος καὶ δῆμος ἡμετέρους γονεῖς στονάχη[σεν], 10

τοὺς πολύπαιδας ἄπαιδας ἐν στέρνοις ἰὸν ἔχοντας,

ὧν βίος ἠμαύρωται παίδων χάριν ὧν τέκον αὐτοί·

καὶ θρῆνος βαρύδουπον ἔχει πατὴρ Εἱλάσιος οἴκοις

σὺν φιλίῃ συνεύνῳ, ἡμετέρῃ μητρὶ Σωφρονίῃ·

λείψατε νῦν θρήνους, γόους, στοναχάς, ἱκνούμεθα νε[κροί], 15

καὶ σκέπ[τεσθε κε]νοῖς Μαιαδίου λείψανον οἴκ[οις,]

τεχθεῖσαν Πρισκιανὴν πενταμηνιαῖον κατ[αθήκην].

... of the children who died prematurely ...

and having looked upon the inconsolable lamentation of the parents here.

Recognize the end of life; therefore play, enjoying yourself in the world,

before looking upon such sorrow on your children's graves.

Who will be a comforter in the house of our parents

or who will end their very painful lamentation in life?

Whom will our father embrace in his arms or whom will he mourn?

He laments Menophilos; will he have Tertulla as a consolation?

Or Maiadios, the best? He increased their sorrow;

The people holding the whole earth sighed for our parents,

who had many children but are childless and have an arrow in their breasts,

whose life is weakened because of the children they produced.

Our father Heilasios has loud-sounding lamentation in the house

together with his dear wife, our mother Sophronie;

now leave off lamentations, wailings, sighings, we the dead beseech you,

and in the empty house look upon Maiadios' relict,

Priskiane, born five months ago, entrusted to you.

. . . . . de liberis intempestivum . . . .Georg Kaibel, Epigrammata Graeca ex Lapidibus Conlecta (Berlin: Reimer, 1878), p. 135 (on lines 5-9):

et lamenta parentum quae solatium-non-capiunt hîc intuitus,

nosce finem vitae: quamobrem lude deliciis-indulgens in mundo,

prius tuorum liberorum luctum talem quam videas in sepulcris.

Quis nostrorum parentum consolator erit in domo,

aut lamenta excludet aerumnosa e vita?

Quem manibus tenebit (parens uterque) aut amplectetur aut quem flebit?

Menophilum luget; Tertullam consolatricem habebit

aut Maeadum optimum? majorem luctum dedit iis.

Omne genus et populus omnis nostros parentes miserabitur,

qui multos-liberos habuere liberorum-orbos, in pectore telum habentes,

quorum vita obscurata est liberorum gratia, quos genuere ipsi.

Et lamenta graviter-sonantia habet pater Ilasius

cum dilecta conjuge, matre nostra, Sophornia.

Linquite jam lamentationes, gemitus, querelas, obtestamur mortui,

et tueamini Maeadii reliquias viduis in aedibus

partam Priscianam, quinque-mensium depositum.

quem pater deflebit? quem consolantem habebit? flet Menophilum: num Tertulla eum consolabitur aut Maeadius? Maeadio et Tertullae uxori vel plura dedit lugenda mala fortuna (πένθος), quippe qui non parentibus solum filii, sed etiam filiolae parentes erepti sint.

Thursday, October 27, 2022

A Stern-Minded Lady

Chester G. Starr, "The History of the Roman Empire 1911-1960,"

Journal of Roman Studies 50.1-2 (1960) 149-160 (at 149):

History is the study of past events, but it is written and rewritten by men and women living in the present. However secluded we may be in library, study, or lecture hall, however oblivious the scholar may appear to the rush of contemporary life, our views of the past are deeply affected by our concerns in the present and by our expectations for the future....Among the recent events which have affected men of reflective minds, the demands of fiercely insistent political creeds have often had unpleasant results. Conscious or unconscious disregard of those historical standards which are one of our greatest inheritances from the nineteenth century can be found even in the product of good scholars.Id. (at 151):

The study of any part of past human development which is directly motivated by present concerns often lies on, or close to, the lunatic fringe of scholarship, whether it be religious, nationalistic, or ideological in impetus.Id. (at 152):

The fundamental unity of modern Western civilization is a concept about which much nonsense, and a little firm thinking, now revolves; and many of us realize that the Western outlook is not the only possible view of the world.Id. (at 153):

Historians of the Empire have been affected not only by changing views of the place of Western civilization but also by new developments within it. I shall take up here only one example, which may serve for many others. The creation, thus, of new techniques for social research and the proliferation of the social studies have attracted a host of practitioners, many of whom still try recurrently to turn themselves into complete scientists. Those of their techniques which are based upon polls, anthropological field studies, high-speed computers, and the like cannot be applied in any degree to the Roman Empire; and a stubborn conservative, bred in the tradition of individual contemplation, may be grateful that this is true.Id. (at 153-154):

I would not have the reader judge that I belong to the school of subjective, idealistic historiography. History, though fashioned by men who inevitably react to contemporary passions and concerns, is basically a reconstruction of past actuality. Clio is a stern-minded lady, who insistently drags her followers back to concrete facts, specifically located in time and space; and our effort must ever be to reanimate those facts soberly, yet with imagination.Id. (at 158):

The study of intellectual history, I fear, sometimes looks too easy. It cannot be treated by cataloguing authors or establishing the existence of sententiae which are borrowed and adapted from generation to generation. The activity of an age cannot be understood if it is chopped into neat segments, labelled Social Life, Religious Movements, and the like. Investigators in this field must have firm general ideas as a basic framework, but must support their concepts by very extensive and very precise detailed investigation. And they ignore political and economic developments only at the great risk of producing spineless, weak interpretations.Id. (at 159, footnote omitted):

Too many students in this field have taken refuge in the treatment of detailed problems solely for their own sake. This is a common characteristic of contemporary scholarship in many areas. In a world so beset by uncertainty, in which old standards have tottered, many of us have sought to gain our own security of mind by working in parvo. The consequences are dangerous. As specialists in numismatics, epigraphy, military archaeology and a host of other narrow ranges, we grow less able to speak to each other on a general common ground.

A Little Classical Anthology

Karl Maurer (1948-2015), An Introduction to Robert Frost: A Talk with Notes. Edited by Adam Cooper and Taylor Posey (Asheville: Taylor Posey, Publisher, 2021), p. 30:

Alcman's description of the world asleep at night (frag. 1); the magical opening lines of Xenophanes' poem about a symposium, which simply names objects in the hall (frag. 89); many quiet passages in Vergil, in which he describes the night (e.g. Aen. 5.835 ff.); the first stanza of 'Poverty' by Thomas Traherne; Coleridge's snapshots in 'Frost at Midnight'; a hundred places in Borges, that do nothing except describe the passing hour. These places, which I love above all others in literature, are those that most embarrass analytical criticism.Alcman, fragment 58, tr. C.M. Bowra, Greek Lyric Poetry (1961; rpt. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), pp. 70-71:

The peaks and the gullies of the mountains are asleep, the headlands and the torrents, the forest and all four-footed creatures that the black earth nourishes, the wild beasts of the mountains and the race of bees and the monsters in the depth of the dark-blue sea, and the tribe of the long-winged birds are asleep.Xenophanes, fragment 1, lines 1-12 (tr. M.L. West):

εὕδουσιν δ' ὀρέων

κορυφαί τε καὶ φάραγγες,

πρώονές τε καὶ χαράδραι

ὕλά θ' ἑρπέτά θ' ὅσσα

τρέφει μέλαινα γαῖα,

θῆρές τ' ὀρεσκῷοι

καὶ γένος μελισσᾶν

καὶ κνώδαλ' ἐν βένθεσσι πορφυρέας ἁλός,

εὕδουσιν δ' οἰωνῶν

φῦλα τανυπτερύγων.

For now the floor is clean, and everybody's handsVergil, Aeneid 5.835-839 (tr. Allen Mandelbaum):

and cups; a servant garlands us with wreaths;

another offers fragrant perfume from a dish;

the mixing-bowl's set up, brimful of cheer,

and further jars of wine stand ready, promising

never to fail—soft wine that smells of flowers.

The frankincense sends out its holy scent all round

the room; there's water, cool and clear and sweet;

bread lies to hand, gold-brown; a splendid table, too,

with cheeses and thick honey loaded down.

The altar in the middle's decked about with flowers;

festivity and song pervade the house.

νῦν γὰρ δὴ ζάπεδον καθαρὸν καὶ χεῖρες ἁπάντων

καὶ κύλικες· πλεκτοὺς δ᾽ ἀμφιτιθεῖ στεφάνους,

ἄλλος δ᾽ εὐῶδες μύρον ἐν φιάλῃ παρατείνει·

κρητὴρ δ᾽ ἕστηκεν μεστὸς ἐϋφροσύνης·

ἄλλος δ᾽ οἶνος ἑτοῖμος, ὃς οὔποτέ φησι προδώσειν,

μείλιχος ἐν κεράμοις, ἄνθεος ὀζόμενος·

ἐν δὲ μέσοις ἁγνὴν ὀδμὴν λιβανωτὸς ἵησιν,

ψυχρὸν δ᾽ ἔστιν ὕδωρ καὶ γλυκὺ καὶ καθαρόν·

παρκέαται δ᾽ ἄρτοι ξανθοὶ γεραρή τε τράπεζα

τυροῦ καὶ μέλιτος πίονος ἀχθομένη·

βωμὸς δ᾽ ἄνθεσιν ἀν τὸ μέσον πάντη πεπύκασται,

μολπὴ δ᾽ ἀμφὶς ἔχει δώματα καὶ θαλίη.

And now damp Night had almost reached her midpoint

along the skies; beneath their oars the sailors

were stretching out on their hard rowing benches,

their bodies sinking into easy rest,

when, gliding lightly from the stars of heaven,

Sleep split the darkened air, cast back the shadows...

iamque fere mediam caeli Nox humida metam

contigerat; placida laxabant membra quiete

sub remis fusi per dura sedilia nautae:

cum levis aetheriis delapsus Somnus ab astris

aëra dimovit tenebrosum et dispulit umbras...

Ancient Times

Paul MacKendrick, The Mute Stones Speak: The Story of Archaeology in Italy, 2nd ed. (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1983), p. 281:

Maximilian, later to be Emperor of Mexico, when he visited Pompeii in 1851, found it terrible, its rooms like painted corpses. Since then, modern archaeological methods (scientific, not miraculous) have brought the corpses to life. What archaeology has presented to us here, as at its best it always does, is not things but people, at work and play, in house and workshop, worshiping and blaspheming, and after their fashion patronizing the arts. So vividly does archaeology reveal them that we are moved to say with Francis Bacon, "These are the ancient times, when the world is ancient, and not those which we account ancient, by a computation backwards from ourselves."

Wednesday, October 26, 2022

Three Types of Men

Hesiod, Works and Days 293-297 (tr. Glenn W. Most):

The man who thinks of everything by himself, considering what will be better, later and in the end—this man is the best of all. That man is fine too, the one who is persuaded by someone who speaks well. But whoever neither thinks by himself nor pays heed to what someone else says and lays it to his heart—that man is good for nothing.Livy 22.29.8 (Minucius speaking; tr. J.C. Yardley):

οὗτος μὲν πανάριστος, ὃς αὐτὸς πάντα νοήσει

φρασσάμενος τά κ' ἔπειτα καὶ ἐς τέλος ᾖσιν ἀμείνω·

ἐσθλὸς δ' αὖ καὶ κεῖνος, ὃς εὖ εἰπόντι πίθηται· 295

ὃς δέ κε μήτ' αὐτὸς νοέῃ μήτ' ἄλλου ἀκούων

ἐν θυμῷ βάλληται, ὃ δ' αὖτ' ἀχρήιος ἀνήρ.

'I have often been told that the best man is he who gives helpful advice, that the man who accepts good advice stands next to him; and that the most inadequate man is he who cannot give advice, but cannot accept it from another, either.'

"saepe ego" inquit, "audivi, milites, eum primum esse virum qui ipse consulat quid in rem sit, secundum eum qui bene monenti oboediat; qui nec ipse consulere nec alteri parere sciat, eum extremi ingenii esse."

A Source of Error

Chester G. Starr, "An Overdose of Slavery,"

Journal of Economic History 18.1 (March, 1958) 17-32 (at 18):

When an erroneous view about some aspect of history is widely and tenaciously held, we may expect to discover compelling reasons of an extraneous character. In particular, the work of the scholar often reflects the ideological currents of the day.Id. (at 31):

[O]ne must be cautious in accepting ancient aristocratic accounts of the immorality of the early Empire. The Roman was a moralist who could not withstand sin but had delightful shudders while committing it.

Miscellany

Aulus Gellius, Attic Nights praef. 2 (tr. J.C. Rolfe):

From Graham Asher:

But in the arrangement of my material I have adopted the same haphazard order that I had previously followed in collecting it. For whenever I had taken in hand any Greek or Latin book, or had heard anything worth remembering, I used to jot down whatever took my fancy, of any and every kind, without any definite plan or order; and such notes I would lay away as an aid to my memory, like a kind of literary storehouse, so that when the need arose of a word or a subject which I chanced for the moment to have forgotten, and the books from which I had taken it were not at hand, I could readily find and produce it.Id. 5-9:

usi autem sumus ordine rerum fortuito, quem antea in excerpendo feceramus. nam proinde ut librum quemque in manus ceperam seu Graecum seu Latinum vel quid memoratu dignum audieram, ita quae libitum erat, cuius generis cumque erant, indistincte atque promisce annotabam eaque mihi ad subsidium memoriae quasi quoddam litterarum penus recondebam, ut quando usus venisset aut rei aut verbi, cuius me repens forte oblivio tenuisset, et libri ex quibus ea sumpseram non adessent, facile inde nobis inventu atque depromptu foret.

[5] For since they had laboriously gathered varied, manifold, and as it were indiscriminate learning, they therefore invented ingenious titles also, to correspond with that idea. [6] Thus some called their books "The Muses," others "Woods", one used the title "Athena's Mantle," another "The Horn of Amaltheia," still another "Honeycomb," several "Meads," one "Fruits of my Reading," another "Gleanings from Early Writers," another "The Nosegay," still another "Discoveries." [7] Some have used the name "Torches," others "Tapestry," others "Repertory," others "Helicon," "Problems," "Handbooks" and "Daggers." [8] One man called his book "Memorabilia," one "Principia," one "Incidentals,", another "Instructions." Other titles are "Natural History," "Universal History," "The Field," "The Fruit-basket," or "Topics." [9] Many have termed their notes "Miscellanies," some "Moral Epistles," "Questions in Epistolary Form," or "Miscellaneous Queries," and there are some other titles that are exceedingly witty and redolent of extreme refinement.Clement of Alexandria, Miscellanies 6.2.1, pp. 422-423 Stählin (tr. J.M.F. Heath):

[5] nam quia variam et miscellam et quasi confusaneam doctrinam conquisiverant, eo titulos quoque ad eam sententiam exquisitissimos indiderunt. [6] namque alii Musarum inscripserunt, alii Silvarum, ille Πέπλον, alius Ἀμαλθείας Κέρας, alius Κηρία, partim Λειμῶνας, quidam Lectionis Suae, alius Antiquarum Lectionum atque alius Ἀνθηρῶν et item alius Εὑρημάτων. [7] sunt etiam qui Λύχνους inscripserint, sunt item qui Στρωματεῖς, sunt adeo qui Πανδέκτας et Ἐλικῶνα et Προβλήματα et Ἐγχειρίδια et Παραξιφίδας. [8] est qui Memoriales titulum fecerit, est qui Πραγματικὰ et Πάρεργα et Διδασκαλικά, est item qui Historiae Naturalis, et Παντοδαπῆς Ἱστορίας, est praeterea qui Pratum, est itidem qui Πάγκαρπον, est qui Τόπων scripserit; [9] sunt item multi qui Coniectanea, neque item non sunt qui indices libris suis fecerint aut Epistularum Moralium aut Epistolicarum Quaestionum aut Confusarum et quaedam alia inscripta nimis lepida multasque prorsum concinnitates redolentia.

So just as in the meadow the flowers blossom in variety and in the paradise garden the planting of the trees that produce fruits on their top branches does not have each of the different species separated according to its kind (the way also some people, picking out blossoms in variety, put together in written form Meadows and Helicons and Honeycombs and Mantles, compilations that delight in learning), the form of our Stromateis has been variegated like a meadow with the things that came by chance to my memory, and that have not been thoroughly purified either by arrangement or by diction, deliberately scattered pell-mell.Many words meaning "miscellany" are etymologically related to food. The Spanish expression olla podrida and its French equivalent pot pourri, translated literally, mean "rotten pot," a kind of stew composed of whatever ingredients are at hand. Metaphorically, they mean any disorganized collection. The word pot is also hidden in English hodge podge, a variant of which is hotch potch, originally hotch pot. In Latin, a lanx satura (whence our satire) means "full platter," and Italian salmagundi is a salad made of various ingredients. Italian pasticcio ("medley," "pastry cake," from pasta) is also behind our pastiche. Gallimaufry comes from French galimafrée, a hash or ragout. Farrago is a direct borrowing from a Latin word meaning "medley, mix of grains for animal feed," itself from far = "grain".

ἐν μὲν οὖν τῷ λειμῶνι τὰ ἄνθη ποικίλως ἀνθοῦντα κἀν τῷ παραδείσῳ ἡ τῶν ἀκροδρύων φυτεία οὐ κατὰ εἶδος ἕκαστον κεχώρισται τῶν ἀλλογενῶν (ᾗ καὶ Λειμῶνάς τινες καὶ Ἑλικῶνας καὶ Κηρία καὶ Πέπλους συναγωγὰς φιλομαθεῖς ποικίλως ἐξανθισάμενοι συνεγράψαντο)· τοῖς δ´ ὡς ἔτυχεν ἐπὶ μνήμην ἐλθοῦσι καὶ μήτε τῇ τάξει μήτε τῇ φράσει διακεκαθαρμένοις, διεσπαρμένοις δὲ ἐπίτηδες ἀναμίξ, ἡ τῶν Στρωματέων ἡμῖν ὑποτύπωσις λειμῶνος δίκην πεποίκιλται. καὶ δὴ ὧδε ἔχοντες ἐμοί τε ὑπομνήματα εἶεν ἂν ζώπυρα, τῷ τε εἰς γνῶσιν ἐπιτηδείῳ, εἴ πως περιτύχοι τοῖσδε, πρὸς τὸ συμφέρον καὶ ὠφέλιμον μετὰ ἱδρῶτος ἡ ζήτησις γενήσεται.

From Graham Asher:

[M]y eye was caught by the strange collocation "Handbooks" and "Daggers", translating Ἐγχειρίδια et Παραξιφίδας.

But Ἐγχειρίδια itself can mean 'daggers', and the fact that 'daggers' comes next suggests that the two titles are variations on the same thing...

Tuesday, October 25, 2022

A Lion in the House

Aeschylus, Agamemnon 717-736 (tr. Richmond Lattimore):

Once a man fostered in his houseSee Bernard M.W. Knox, "The Lion in the House (Agamemnon 717–36 [Murray])," Classical Philology 47 (1952) 17–25.

a lion cub, from the mother's milk

torn, craving the breast given.

In the first steps of its young life

mild, it played with children

and delighted the old.

Caught in the arm's cradle

they pampered it like a newborn child,

shining eyed and broken to the hand

to stay the stress of its hunger.

But it grew with time, and the lion

in the blood strain came out; it paid

grace to those who had fostered it

in blood and death for the sheep flocks,

a grim feast forbidden.

The house reeked with blood run

nor could its people beat down the bane,

the giant murderer's onslaught.

This thing they raised m their house was blessed

by God to be priest of destruction.

ἔθρεψεν δὲ λέοντος ἶ-

νιν δόμοις ἀγάλακτον οὕ-

τως ἀνὴρ φιλόμαστον,

ἐν βιότου προτελείοις 720

ἅμερον, εὐφιλόπαιδα

καὶ γεραροῖς ἐπίχαρτον.

πολέα δ' ἔσκ' ἐν ἀγκάλαις

νεοτρόφου τέκνου δίκαν,

φαιδρωπὸς ποτὶ χεῖρα σαί- 725

νων τε γαστρὸς ἀνάγκαις.

χρονισθεὶς δ' ἀπέδειξεν ἦ-

θος τὸ πρὸς τοκέων· χάριν

γὰρ τροφεῦσιν ἀμείβων

μηλοφόνοισι μάταισιν 730

δαῖτ' ἀκέλευστος ἔτευξεν,

αἵματι δ' οἶκος ἐφύρθη,

ἄμαχον ἄλγος οἰκέταις,

μέγα σίνος πολυκτόνον.

ἐκ θεοῦ δ' ἱερεύς τις ἄ- 735

τας δόμοις προσεθρέφθη.

Animal Dedicatees

Dedication of Josiah Ober, Demopolis: Democracy before Liberalism in Theory and Practice (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017):

"Walls of Roman houses at Vaison-la-Romaine (photo by the author)" in James C. Anderson, Jr., Roman Architecture in Provence (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013): Related posts:

Id., pp. 91-92:For Denise, Spike, Stella, Blanche, Bindi, and Enki.

They pounced.

The intuition that animals suffer if they are denied any opportunity to exercise their constitutive capacities (as well as if they are deprived of food, shelter, etc.) is, I suppose, at the core of many people's beliefs about acts constituting cruelty to animals. If that intuition is correct, a cat possessing all other goods (food, shelter, etc.), but denied any opportunity to exercise its capacity to pounce, whether on prey or prey analogues (toys, teasers, etc.), could not reasonably be said to have flourished over the course of its life as a cat. Those responsible for keeping cats in small cages over the course of their lives are blameworthy, in that they do harm to those cats. The cat that lives out its life in a cage suffers a deprivation that ought not, under ordinary circumstances, be suffered by any cat. There may be some consequentialist justification for someone to keep some cats in small cages. But the fact remains that the cat in a cage lives a fundamentally less good life than does the cat with an opportunity to pounce, all other things being equal.Of the animals in the dedication the first four were ferrets, the last two Bengal cats (Josiah Ober, per litteras).

"Walls of Roman houses at Vaison-la-Romaine (photo by the author)" in James C. Anderson, Jr., Roman Architecture in Provence (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013): Related posts:

Hot Love

Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, Erinnerungen 1848–1914, 2. Aufl. (Leipzig: K.F. Koehler, 1928), p. 104 (my translation):

The ultimate task of philological-historical scholarship is, through the power of the scientifically trained imagination, to resurrect past life, feeling, thought, belief, so that all that is of invigorating power in that past may continue to have an effect on the present and future. For this, the head must be cool, but hot love must burn in the heart. Only Eros leads to the contemplation of truth and the eternally vital.

Die letzte Aufgabe der philologisch-historischen Wissenschaft ist, durch die Kraft der wissenschaftlich geschulten Phantasie vergangenes Leben, Fühlen, Denken, Glauben wieder lebendig zu machen, auf daß alles, was von belebender Kraft in jener Vergangenheit ist, auf die Gegenwart und Zukunft fortwirke. Dazu muß der Kopf kühl sein, aber heiße Liebe im Herzen brennen. Nur der Eros führt zum Anschauen der Wahrheit und des ewig Lebendigen.

Inequality

Chester G. Starr, The Aristocratic Temper of Greek Civilization (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992), p. 4:

Elites these days are universally scorned even by academic elites.

This is odd. When one examines ancient literature rather than modern surveys, aristocrats are always in the foreground historically, philosophically, and artistically. They at least had no doubt that they were the most important element in society and established its attitudes and values; slaves on the other hand were only occasionally considered. For the sake of clarity I should offer here a preliminary definition of the term "aristocrats" as being those who shared a cultured pattern of life and values consciously conceived and upheld from generation to generation. In all Greek states such groups were limited in numbers but firmly considered themselves the "best"; their claims were normally accepted, even cherished by other, lower classes.

[....]

Modern opinion has so exalted the demand for egalitarianism in recent years that the historical existence of social inequality over centuries is muffled or denied; in consequence the aristocrats of ancient Greece too often have been placed in an unwarrantedly hostile light. Here, as in virtually every aspect of their culture, the Greeks were brutally clear-headed in their acceptance of the fact that not all men and women were equal, though one may feel that they at times carried this acceptance to extremes in exploiting their privileged political, economic, and social status.

Monday, October 24, 2022

Two Medical Oaths

Oath sworn by University of Minnesota Medical School's Class of 2026 (White Coat Ceremony, Friday, August 19, 2022, Northrop Memorial Auditorium):

With gratitude, we, the students of the University of Minnesota Twin Cities Medical School Class of 2026, stand here today among our friends, families, peers, mentors and communities who have supported us in reaching this milestone. Our institution is located on Dakota land. Today many indigenous people throughout the state, including the Dakota and the Ojibwe, call the Twin Cities home; we also recognize this acknowledgment is not enough.Members of the Oath Writing Committee:

We commit to uprooting the legacy and perpetuation of structural violence deeply embedded within the healthcare system. We recognize inequities built by past and present traumas rooted in white supremacy, colonialism, the gender binary, ableism, and all forms of oppression. As we enter this profession with opportunity for growth, we commit to promoting a culture of antiracism, listening and amplifying voices for positive change. We pledge to honor all indigenous ways of healing that have been historically marginalized by Western medicine. Knowing that health is intimately connected with our environment, we commit to healing our planet and communities.

We vow to embrace our role as community members and strive to embody cultural humility. We promise to continue restoring trust in the medical system and fulfilling our responsibility as educators and advocates. We commit to collaborating with social, political and additional systems to advance health equity. We will learn from the scientific innovations made before us and pledge to advance and share this knowledge with peers and neighbors. We recognize the importance of being in community with, and advocating for, those we serve.

We promise to see the humanity in each patient we serve, empathize with their lived experiences, and be respectful of their unique identities. We will embrace deep and meaningful connections with patients, and strive to approach every encounter with humility and compassion. We will be authentic and present in our interactions with patients and hold ourselves accountable for our mistakes and biases. We promise to communicate with our patients in an accessible manner to empower their autonomy. We affirm that patients are the experts of their own bodies, and will partner with them to facilitate holistic wellbeing.

We will be lifelong learners, increasing our competence in the art and science of medicine. We recognize our limits and will seek help to bridge those gaps through interprofessional collaboration. We will prioritize care for the mind, body and soul of not only our patients, but of our colleagues and selves With this devotion, we will champion our personal wellness and bring the best versions of ourselves to our profession. We will support one another as we grow as physicians and people. We are honored to accept these white coats. In light of their legacy as a symbol of power, prestige and dominance, we strive to reclaim their identity as a symbol of responsibility, humility and loving kindness.

Divya Alley, Haley Brahmbhatt, Dawson Cooper, Eva Elder, Zuag Paj Her, Michael Hernandez, Olivia Kaus, Christina Lan, Logan L. Lineburg, John Mallow, Braeden Malotky, Sanjana Molleti, Heba Sandozi, Cassandra Sundaram, and Colin WhitmoreLudwig Edelstein's translation of the Hippocratic Oath, with the ancient Greek interspersed:

I swear by Apollo Physician and Asclepius and Hygieia and Panaceia and all the gods and goddesses, making them my witnesses,Related post: Ancient Oaths.

Ὄμνυμι Ἀπόλλωνα ἰητρὸν, καὶ Ἀσκληπιὸν, καὶ Ὑγείαν, καὶ Πανάκειαν, καὶ θεοὺς πάντας τε καὶ πάσας, ἵστορας ποιεύμενος,

that I will fulfill according to my ability and judgment this oath and this covenant:

ἐπιτελέα ποιήσειν κατὰ δύναμιν καὶ κρίσιν ἐμὴν ὅρκον τόνδε καὶ ξυγγραφὴν τήνδε·

To hold him who has taught me this art as equal to my parents and to live my life in partnership with him, and if he is in need of money to give him a share of mine, and to regard his offspring as equal to my brothers in male lineage and to teach them this art—if they desire to learn it—without fee and covenant;

ἡγήσασθαι μὲν τὸν διδάξαντά με τὴν τέχνην ταύτην ἴσα γενέτῃσιν ἐμοῖσι, καὶ βίου κοινώσασθαι, καὶ χρεῶν χρηΐζοντι μετάδοσιν ποιήσασθαι, καὶ γένος τὸ ἐξ ωὐτέου ἀδελφοῖς ἴσον ἐπικρινέειν ἄῤῥεσι, καὶ διδάξειν τὴν τέχνην ταύτην, ἢν χρηΐζωσι μανθάνειν, ἄνευ μισθοῦ καὶ ξυγγραφῆς,

to give a share of precepts and oral instruction and all the other learning to my sons and to the sons of him who has instructed me and to pupils who have signed the covenant and have taken an oath according to the medical law, but no one else.

παραγγελίης τε καὶ ἀκροήσιος καὶ τῆς λοιπῆς ἁπάσης μαθήσιος μετάδοσιν ποιήσασθαι υἱοῖσί τε ἐμοῖσι, καὶ τοῖσι τοῦ ἐμὲ διδάξαντος, καὶ μαθηταῖσι συγγεγραμμένοισί τε καὶ ὡρκισμένοις νόμῳ ἰητρικῷ, ἄλλῳ δὲ οὐδενί.

I will apply dietetic measures for the benefit of the sick according to my ability and judgment; I will keep them from harm and injustice.

διαιτήμασί τε χρήσομαι ἐπ' ὠφελείῃ καμνόντων κατὰ δύναμιν καὶ κρίσιν ἐμὴν, ἐπὶ δηλήσει δὲ καὶ ἀδικίῃ εἴρξειν.

I will neither give a deadly drug to anybody who asked for it, nor will I make a suggestion to this effect.

οὐ δώσω δὲ οὐδὲ φάρμακον οὐδενὶ αἰτηθεὶς θανάσιμον, οὐδὲ ὑφηγήσομαι ξυμβουλίην τοιήνδε·

Similarly I will not give to a woman an abortive remedy.

ὁμοίως δὲ οὐδὲ γυναικὶ πεσσὸν φθόριον δώσω.

In purity and holiness I will guard my life and my art.

ἁγνῶς δὲ καὶ ὁσίως διατηρήσω βίον τὸν ἐμὸν καὶ τέχνην τὴν ἐμήν.

I will not use the knife, not even on sufferers from stone, but will withdraw in favor of such men as are engaged in this work.

οὐ τεμέω δὲ οὐδὲ μὴν λιθιῶντας, ἐκχωρήσω δὲ ἐργάτῃσιν ἀνδράσι πρήξιος τῆσδε.

Whatever houses I may visit, I will come for the benefit of the sick, remaining free of all intentional injustice, of all mischief and in particular of sexual relations with both female and male persons, be they free or slaves.

ἐς οἰκίας δὲ ὁκόσας ἂν ἐσίω, ἐσελεύσομαι ἐπ' ὠφελείῃ καμνόντων, ἐκτὸς ἐὼν πάσης ἀδικίης ἑκουσίης καὶ φθορίης, τῆς τε ἄλλης καὶ ἀφροδισίων ἔργων ἐπί τε γυναικείων σωμάτων καὶ ἀνδρῴων, ἐλευθέρων τε καὶ δούλων.

What I may see or hear in the course of the treatment or even outside of the treatment in regard to the life of men, which on no account one must spread abroad, I will keep to myself, holding such things shameful to be spoken about.

ἃ δ' ἂν ἐν θεραπείῃ ἢ ἴδω, ἢ ἀκούσω, ἢ καὶ ἄνευ θεραπηΐης κατὰ βίον ἀνθρώπων, ἃ μὴ χρή ποτε ἐκλαλέεσθαι ἔξω, σιγήσομαι, ἄῤῥητα ἡγεύμενος εἶναι τὰ τοιαῦτα.

If I fulfill this oath and do not violate it, may it be granted to me to enjoy life and art, being honored with fame among all men for all time to come;

ὅρκον μὲν οὖν μοι τόνδε ἐπιτελέα ποιέοντι, καὶ μὴ ξυγχέοντι, εἴη ἐπαύρασθαι καὶ βίου καὶ τέχνης δοξαζομένῳ παρὰ πᾶσιν ἀνθρώποις ἐς τὸν αἰεὶ χρόνον·

if I transgress it and swear falsely, may the opposite of all this be my lot.

παραβαίνοντι δὲ καὶ ἐπιορκοῦντι, τἀναντία τουτέων.

Inappropriate Adjectives

Frederick M. Combellack, "Two Blameless Homeric Characters,"

American Journal of Philology 103.4 (Winter, 1982) 361-372 (at 361; footnote omitted):

A familiar feature of Homer's use of adjectives is what has come to be called the "generic" use. The adjective refers to what the character or the phenomenon is habitually, even though the word may be irrelevant or even inappropriate on a given occasion. The clothes of the Phaeacian royal family are "bright" even when they are dirty clothes on their way to the laundry (Od. 6.74). Aphrodite is laughter-loving even when she is in great pain and complaining to her mother about the wound that Diomedes has given her (Iliad 5.375).

These occasional inappropriate adjectives created a problem for the Homerists of antiquity, and they devised a solution (attributed in the scholia to Aristarchus). Their λύσις was: οὐ τότε ἀλλὰ φύσει "not at that time, but by nature."

A Thorough and Accurate Knowledge of the Poems

George M. Calhoun, "Polity and Society," in Alan J.B. Wace and Frank. H. Stubbings, edd., A Companion to Homer (London: Macmillan & Co Ltd, 1962), pp. 431-462 (at 432):

What is most needed is a thorough and accurate knowledge of the poems, conjoined with the sort of common sense that would be used in the study of a modern author. This can be better attained by reading Homer and consulting the literature of criticism than by reading the literature of criticism and consulting Homer.

Of a Mouse and a Man

John Scheid, "Roman Theologies in the Roman Cities of Italy

and the Provinces," in Jonathan J. Price et al., edd., Rome: An Empire of Many Nations. New Perspectives on Ethnic Diversity and

Cultural Identity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021), pp. 116-134 (at 132-133):

We now leave Belgica to go first to Raetia, to the city of Cambodunum (Kempten), where a lead curse tablet was found with the following inscription:39 “Silent Mutes! Let Quartus be dumb, or be distraught; he wanders like a fleeing mouse or a bird before a basilisk, let his mouth be mute, Mutes! Let the Mutes be dread! Let the Mutes remain silent! Mutes! Mutes! Let Quartus go mad, let Quartus be brought to the Erinyes and Orcus. Let the Silent Mutes remain silent near the golden doors.” A classic curse tablet, but what is less classic is the invocation made to the Mutae Tacitae. This goddess, in the singular, is set by Ovid in the etiological myth of the Feralia, the festival of the dead at the end of February. This is the story that is connected to the birth of the Lares. A talkative nymph, Lara, from Lala, etymologically the “Talkative one,” revealed to Juno that her husband Jupiter was going to woo the nymph Juturna. She was punished and sent by the all-powerful to the underworld, to silence. It was Mercury who took her. Mercury, who was also the god of thieves and thugs, rapes her on the way. She clearly remained there and gave birth to two boys, who became the Lares. On our fragment of a curse tablet, Ovid’s Tacita Muta has become the Mutae Tacitae, following a relatively conventional practice that will not surprise us. The Eileithyiae, the Furrinae, the Camenae and others attest to this, being sometimes in the plural, sometimes in the singular. What is extraordinary, however, is the fact that Tacita Muta was only known to Ovid.40 His etiology is a small masterpiece of the kind, to the extent that he could be considered as having invented everything, including the name of the goddess. In addition, we will note the fate reserved for the brave Quartus, sent to Orcus like Lara, and the role attributed to the mouse that already intervenes in the rite as it is described by Ovid (placing incense in a hole dug by a mouse), as if the author of the curse tablet were winking at the poet with these allusions.Because erret is subjunctive, not indicative, instead of "he wanders like a fleeing mouse or a bird before a basilisk" I would translate "let him wander like a fleeing mouse or a bird before a basilisk." I learned about this curse tablet from Paul MacKendrick, Romans on the Rhine: Archaeology in Germany (New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1970), p. 85, who retains the force of the subjunctive:

But — and this is what interests us — we see the name Mutae Tacitae show up in Raetia! From two things to one. Either Tacita Muta was a real divine figure, or the author of the curse tablet was literate and had composed his invocation according to Ovid, himself creating a specialized goddess intended to silence a rival or an enemy. Which solution to choose? I am inclined toward the first, for the change from the singular to the plural Tacitae indicates in my opinion a religious practice known for decades. This was also the case for Furrina, found in the singular in the name of her lucus, until the time of Varro, in the middle of the first century BC, and then it appears in the plural on inscriptions from the end of the second and third centuries AD found in this sacred wood.

39 AE 1958, 150 = Chapot and Laurot 2001: n° L 78 (Cambodunum, Kempten, Rhétie): Mutae tacitae! ut mutus sit | Quartus agitatus erret ut mus | fugiens aut avis adversus basyliscum | ut e[i]us os mutu(m) sit, Mutae | Mutae [d]irae sint! Mutae | tacitae sint! Mutae | [Qu]a[rt]us ut insaniat, // Vt Eriniis rutus sit et | Quartus Orco ut Mutae | Tacitae ut mut[ae s]int | ad portas aureas. Cf. Cf. R. Egger 1957.

40 Bettini 2006: 149–72.

One of the curiosities of the museum is a curse-tablet, inscribed as usual on lead, expressing the pious hope that the object of the curse "may run about frantic like a fleeing mouse" ("agitatus erret ut mus fugiens").Cf. the translation in Stuart McKie, Living and Cursing in the Roman West: Curse Tablets and Society (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2022), pp. 197-198:

Silent Mutes, thus Quartus should be mute, he should scurry around like a fleeing mouse or bird in the face of a basilisk, so should his mouth be mute, Mutes. May the Mutes be dreadful, may the Mutae [sic] be silent. May Quartus be driven mad, may Quartus be driven to the Furies and to Orcus. May the Mutae be silent, mute and silent at the golden gates.On rutus see the Oxford Latin Dictionary s.v. (as a noun), sense 2 ("An act of rushing or hurrying"), citing only this curse tablet.

Sunday, October 23, 2022

Hoards

Max Martin, "Wealth and Treasure in the West, 4th to 7th Century," tr. Martin Brady, in Leslie Webster and Michelle Brown, edd., The Transformation of the Roman World, A.D. 400–900 (London: British Museum Press, 1997), pp. 48-66, with Plates 13-18, 30-31, 60 (at 63-64):

A single, unrecovered hoard can to some extent be seen as evidence of a sporadic or local discontinuity of ownership. On the other hand, geographical and chronological concentrations of hoards do not simply amount to several sporadic discontinuities, but may instead represent a widespread, or indeed complete, discontinuity in the owners concerned, or even of the entire social stratum to which they belonged. It must always be borne in mind that an unknown number of hoards may have immediately been expropriated by new owners, with the result that there may well have been a considerably greater number of discontinuities than we are able to ascertain today. At any rate there could not have been fewer.Id., Plate 60, with caption "Roman gold and silver coins from the Hoxne hoard, deposited in the early fifth century. (Heirs of Rome, cat. 5a.)":

Where Are They Now?

Hugh Kenner (1923-2003), The Pound Era (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971; rpt. 1974), pp. 76-77:

Some things were current once that are current no longer. A public for an inexpensive bilingual Dante — Italian text, notes, and a facing version in unpretentious prose — was once discoverable in England in sufficient numbers to circulate thousands upon thousands of elegant pocket-sized volumes, price one shilling. Rossetti, not Milton, had prepared that taste, and J.M. Dent began the Temple Dante with the Paradiso. With its gravure frontispiece “after Botticelli,” it was issued in 1899 and reprinted 1900, 1901, 1903, 1904, 1908, 1910, 1912. . . . An afternote cites a Dante Primer also priced (1899) at one shilling. Inferno and Purgatorio followed, then the Convivio, then the Latin Works. By 1906 The Vita Nuova and Canzonieri completed a six-volume set. It was not presumed that the reader knew Italian, but that, “possessing some acquaintance with Latin or one of the Romance languages,” he would welcome a prose guide “to the very words of the master in the original.”

[....]

In 1902 the numerous students of Dante (where are they now?) could buy H.J. Chaytor’s The Troubadours of Dante, which offered as much as any one is likely to require who does not propose to make a special study of Provencal.” This meant working through 46 poems with a glossary, a grammar, and notes, unassisted by translations. People with Latin and French, who had been sipping at old Italian, seem not to have thought this formidable.

[....]

The collapse of that public, its supersession by folk absorbed in introspection and politics, is an unwritten story. The printing history of the Temple Paradiso affords an informal graph. The 13 years up to 1912 required eight printings. After a wartime hiatus demand began to slack off: five printings in 11 years. The copy from which I take these data was printed in 1930, not sold until 1946.

Phrygians v. Thracians

Menander, The Shield 241-244 (tr. Norma Miller):

WAITER: Where d'you come from?

DAOS: From Phrygia.

WAITER: Then you're no good, you're a queer. Only Thracians are real men. Getans — God, what heroes!

(Τρ) ποταπός ποτ' εἶ;

(Δα) Φρύξ. (Τρ) οὐδὲν ἱερόν· ἀνδρόγυνος. ἡμεῖς μόνοι

οἱ Θρᾶικές ἐσμεν ἄνδρες· οἱ μὲν δὴ Γέται,

Ἄπολλον, ἀνδρεῖον τὸ χρῆμα.

Our Doctrines

Pierre Hadot, Plotinus or The Simplicity of Vision, tr. Michael Chase (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), pp. 17-18, quoting Enneads V 1, 8 10-14:

Our doctrines are not novel nor do they date from today: they were stated long ago, but not in an explicit way. Our doctrines are explanations of those older ones, and they use Plato's own words to prove that they are ancient.A.H. Armstrong's translation and note:

καὶ εἶναι τοὺς λόγους τούσδε μὴ καινοὺς μηδὲ νῦν, ἀλλὰ πάλαι μὲν εἰρῆσθαι μὴ ἀναπεπταμένως, τοὺς δὲ νῦν λόγους ἐξηγητὰς ἐκείνων γεγονέναι μαρτυρίοις πιστωσαμένους τὰς δόξας ταύτας παλαιὰς εἶναι τοῖς αὐτοῦ τοῦ Πλάτωνος γράμμασιν.

And [it follows] that these statements of ours are not new; they do not belong to the present time, but were made long ago, not explicitly, and what we have said in this discussion has been an interpretation of them, relying on Plato's own writings for evidence that these views are ancient.3Hat tip: Eric Thomson.

3 The belief that the true doctrines are present, but often not explicit, in the writings regarded as traditionally authoritative is, for obvious reasons, essential for pagan and Christian traditionalists of the first centuries A.D. (and for Christian traditionalists later): cp. Origen De Principiis I 3.

Husband and Wife

Funerary stele of a married couple, from the Via Statilia in Rome, ca. 50 BC (Rome, Musei Capitolini/Centrale Montemartini, inv. no. MC 2142), photographs from Valentin Kockel, Porträtreliefs stadtrömischer Grabbauten: ein Beitrag zur Geschichte und zum Verständnis des spätrepublikanisch-frühkaiserzeitlichen Privatporträts (Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern, 1993 = Beiträge zur Erschließung hellenistischer und kaiserzeitlicher Skulptur und Architektur, 12), Tafeln 10a, 12a-b, 14a-b:

See also Kockel, pp. 94-95.

Saturday, October 22, 2022

Arrows

Pseudo-Hesiod, The Shield 129-134 (tr. Glenn W. Most):

After this he cast around his chest the hollow quiver; many arrows were inside, chilling, givers of speechless death: for in front they held death and trickled with tears, in the middle they were smooth, very long, and in back they were covered with the feathers of a fiery red eagle.The same, tr. Barry Powell:

κοίλην δὲ περὶ στήθεσσι φαρέτρην

κάββαλεν ἐξόπιθεν· πολλοὶ δ' ἔντοσθεν ὀιστοὶ 130

ῥιγηλοί, θανάτοιο λαθιφθόγγοιο δοτῆρες·

πρόσθεν μὲν θάνατόν τ' εἶχον καὶ δάκρυσι μῦρον,

μέσσοι δὲ ξεστοί, περιμήκεες, αὐτὰρ ὄπισθε

μόρφνοιο φλεγύαο καλυπτόμενοι πτερύγεσσιν.

Across his chest he cast behindF.A. Paley ad loc.:

him a hollow quiver. There were many arrows in it, shivery,

the givers of speechless destruction. In front they held death,

trickling with tears. The shafts were smooth and very long,

and at their ends they were covered by the feathers of a reddish-brown

eagle.

Thomas Edwards' Canons of Criticism

Quoted in Albert H. Tolman, Falstaff and Other Shakespearean Topics (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1925), pp. 244-246:

I. A Professed Critic has a right to declare, that his Author wrote whatever he thinks he should have written; with as much positiveness, as if he had been at his Elbow.

II. He has a right to alter any passage, which he does not understand.

III. These alterations he may make, in spite of the exactness of the measure.

IV. Where he does not like an expression, and yet cannot mend it; He may abuse his Author for it.

V. Or He may condemn it, as a foolish interpolation.

VI. As every Author is to be corrected into all possible perfection, and of that perfection the Professed Critic is the sole judge; He may alter any word or phrase, which does not want amendment, or which will do; provided He can think of any thing which he imagines will do better.

VII. He may find-out obsolete words, or coin new ones; and put them in the place of such, as He does not like, or does not understand.

VIII. He may prove a reading, or support an explanation, by any sort of reasons; no matter whether good or bad.

IX. He may interpret his Author so; as to make him mean directly contrary to what He says.

X. He should not allow any poetical licences, which He does not understand.

XI. He may make foolish amendments or explanations, and refute them; only to enhance the value of his critical skill.

XII. He may find out an immodest or immoral meaning in his author; where there does not appear to be any hint that way.

XIII. He needs not attend to the low accuracy of orthography or pointing; but may ridicule such trivial criticisms in others.

XIV. Yet, when he pleases to condescend to such work, he may value himself upon it; and not only restore lost puns, but point-out such quaintnesses, where perhaps the author never thought of it.

XV. He may explane a difficult passage, by words absolutely unintelligible.

XVI. He may contradict himself; for the sake of shewing his critical skill on both sides of the question.

XVII. It will be necessary for the profess'd critic to have by him a good number of pedantic and abusive expressions; to throw-about upon proper occasions.

XVIII. He may explane his Author, or any former Editor of him; by supplying such words, or pieces of words, or marks, as he thinks fit for that purpose.

XIX. He may use the very same reasons for confirming his own observations; which He has disallowed in his adversary.

XX. As the design of writing notes is not so much to explane the Author's meaning, as to display the Critic's knowledge; it may be proper, to shew his universal learning, that He minutely point out, from whence every metaphor and allusion is taken.

XXI. It will be proper, in order to shew his wit, especially if the critic be a married man, to take overy opportunity of sneering at the fair sex.

XXII. He may misquote himself, or any body else, in order to make an occasion of writing notes; when He cannot otherwise find one.

XXIII. The Profess’d Critic, in order to furnish his quota to the bookseller, may write NOTES OF NOTHING; that is, Notes, which either explane things which do not want explanation; or such as do not explane matters at all, but merely fill-up so much paper.

XXIV. He may dispense with truth; in order to give the world a higher idea of his parts, or of the value of his work.

XXV. He may alter any passage of his author, without reason and against the Copies; and then quote the passage so altered, as an authority for altering any other.

Revel

One Turns Backward

Gustaf Sobin (1935-2005), Ladder of Shadows: Reflecting on Medieval Vestige

in Provence and Languedoc (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), p. 8:

The past draws. It draws, I feel, to the extent that the present, the cultural and ultimately the spiritual present, has failed to generate generative image: the kind in which societies might come to recognize their veritable identity. In default of such image—such eloquent mirror—one turns backward. Goes under.

[....]

Against the cultural poverty of one's own times, it seems befitting, I feel, to travel under. Examine vestige.

Friday, October 21, 2022

Gurdus

Quintilian 1.5.57 (tr. H.E. Butler):

Thesaurus Linguae Latinae 6,2:2359: A. Walde and J.B. Hoffmann, Lateinisches etymologisches Wörterbuch, 3. Aufl., Bd. I (Heidelberg: Carl Winter, 1938), p. 627: Alfred Ernout and Alfred Meillet, Dictionnaire étymologique de la langue latine, 4th ed. rev. Jacques André (Paris: Klincksieck, 2001), p. 285: Michiel de Vaan, Etymological Dictionary of Latin and the Other Italic Languages (Leiden: Brill, 2008), p. 275: See also Nicholas Zair, "Latin bardus and gurdus," Glotta 94 (2018) 311-318 (at 314-317).

I have heard that gurdus, which is colloquially used in the sense of "stupid," is derived from Spain.Alessandro Garcea and Valeria Lomanto, "Gellius and Fronto on Loanwords and Literary Models: Their Evaluation of Laberius," in Leofranc Holford-Strevens and Amiel Vardi, edd., The Worlds of Aulus Gellius (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), pp. 41-64 (at 59, n. 55):

gurdos, quos pro stolidis accipit vulgus, ex Hispania duxisse originem audivi.

On Quintilian’s testimony, which has long been debated by both literary and linguistic scholars, see e.g. F. Schöll, 'Wortforschung', 313–17, and J. Cousin, 'Problèmes', 63–4: both scholars acknowledge the vulgar connotation of gurdus, but while the former allows its Spanish origin, the latter doubts it.The references are to Fritz Schöll, "Zur lateinischen Wortforschung," Indogermanische Forschungen 31 (1912-1913) 309-320, and Jean Cousin, "Problèmes biographiques et littéraires relatifs à Quintilien," Revue des Etudes Latines 9 (1931) 62–76.

Thesaurus Linguae Latinae 6,2:2359: A. Walde and J.B. Hoffmann, Lateinisches etymologisches Wörterbuch, 3. Aufl., Bd. I (Heidelberg: Carl Winter, 1938), p. 627: Alfred Ernout and Alfred Meillet, Dictionnaire étymologique de la langue latine, 4th ed. rev. Jacques André (Paris: Klincksieck, 2001), p. 285: Michiel de Vaan, Etymological Dictionary of Latin and the Other Italic Languages (Leiden: Brill, 2008), p. 275: See also Nicholas Zair, "Latin bardus and gurdus," Glotta 94 (2018) 311-318 (at 314-317).

Advice

Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum VI 16169 (my translation):

Gnaeus Cornelius Bassus, son of Gnaeus, of the Aniensian tribe.The stone: Franz Buecheler, Carmina Latina Epigraphica (Leipzig: B.G. Teubner, 1895), p. 44, number 85: Hat tip: Eric Thomson.

Born eighteen years ago I lived as well as I could,

dear to my father and all my friends.

Jest, play, I encourage you: there is the utmost seriousness here.

His slave Fortunatus set this up.

Cn(aeus) Cornelius Cn(aei) f(ilius) An(iensi) Bassus

decem et octo annorum natus vixi ut potui bene,

gratus parenti atque amicis omnibus.

ioceris, ludas hortor: hic summa est severitas.

posuit Fortunatus ser(vus)

Once Bitten, Twice Shy

Menander, The Shield 27-30 (tr. Stanley Ireland):

But not being totally successful can be an advantage, so it seems. Someone who's taken a knock is also on his guard, but in our case over-confidence led to slack discipline in the face of what was to come.A.W. Gomme and F.H. Sandbach ad loc.:

ἦν δ' ὡς ἔοικε καὶ τὸ μὴ πάντ' εὐτυχεῖν

χρήσιμον· ὁ γὰρ πταίσας τι καὶ φυλάττεται.

ἡμᾶς δ' ἀτάκτους πρὸς τὸ μέλλον ἤγαγε

τὸ καταφρονεῖν.

Epitaph of a Pankratiast

Reinhold Merkelbach and Josef Stauber, edd., Steinepigramme aus dem griechischen Osten, Bd. 3: Der „Ferne Osten“ und das Landesinnere bis zum Tauros (München: K.G. Säur, 2001), p. 323, number 16/34/37 (click once or twice to enlarge):

Werner Peek, Griechische Vers-Inschriften, Vol. I: Grab-Epigramme (Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 1955), p. 69, number 263:

Simplified transcription of the Greek:

βουλευτής περ ἐὼν [⏑⏑– τὸν τύμβον] ἔτευξεν.Translation:

εἰδὼς θνητογόνων τέρματα τοῦ βιότου,

εὐπατρίδης γεγαὼς οὗτος, φίλε, καὶ σθενέγαυρος

πολλοὺς ἀθλητὰς ἤνυσε πανκρατίῳ.

ἀλλὰ πόνου τόδε κῦδος· ὁ ζῶν δὲ τρυφῆς ἀπόλαυσον,

πρὶν σὲ λιπῖν τὸ φάος· τὰ γὰρ ὧδε κάτω μ' ἐπερώτα.

Being a councillor [...] he built the tomb,

knowing the limits of the life of those born of mortal parents.

Being of noble family, o friend, and exulting in his strength,

he defeated many combatants in the pankration.

But this is the renown of toil. You who live, enjoy luxury,

before you leave the light; for ask me about the things here below.

Thursday, October 20, 2022

Stronger

Phocylides, fragment 4 Gentili and Prato, 8 West (tr. Richmond Lattimore):

Phocylides said this also: a city that's small and is foundedThe same, tr J.M. Edmonds:

on a cliff's edge, well governed, is stronger than Nineveh crazy.

καὶ τόδε Φωκυλίδεω· πόλις ἐν σκοπέλῳ κατὰ κόσμον

οἰκέουσα σμικρὴ κρέσσων Νίνου ἀφραινούσης.

Thus also spake Phocylides—A little state living orderly in a high place is stronger than a block-headed Ninevah.

Athletes

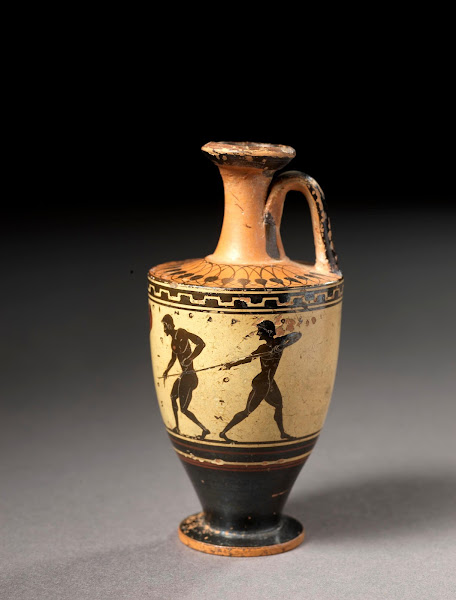

Lekythos attributed to the Kephisophon Painter, ca. 500 B.C. (Toronto, Royal Ontario Museum 963.59):

See Henry R. Immerwahr, "A Lekythos in Toronto and the Golden Youth of Athens," in Studies in Attic Epigraphy, History, and Topography: Presented to Eugene Vanderpool (Princeton: American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 1982 = Hesperia Supplements, 19), pp. 59–65 and Plate 6.

Genealogy

Robert Fowler, "Martin Litchfield West, 23 September 1937 - 13 July 2015," Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the British Academy 17 (2018) 89–120 (at 92):

In a sparkling and typically amusing (unpublished) memoir of his childhood written for his family, West tells how on both parents’ sides he could lay dubious claim to royal ancestry: John Stainthorpe’s mother was said to have been an illegitimate daughter of George, the second Marquis of Normanby, and thus descended from James II; Robert West traced his lineage (via a great-great-grandmother who had eloped with the gardener) to Sir William Courtenay, ‘de jure eighth Earl of Devon and second Viscount of Powderham Castle’. Consequently, West calculated, he was tenth cousin to the Queen. More than that, the ultimate ancestor of all the royals, Egbert of Wessex, was separated by a mere twenty generations from Woden. ‘Once’, he confesses, ‘in filling up a form for some French biographical reference work, I amused myself by naming him as my ancestor. And so it appeared in my entry: “Ascendance: Woden, dieu germanique”.’Id. (at 93, quoting West):

One does have—at least I have—a deep-seated desire for a tribal identity. I always thought of myself as an Englishman, and now I have learned how I can think of myself as a Briton too. Having grown up during the Second World War, I could hardly avoid being imbued with patriotic feeling, which I have never disavowed. I cannot imagine living permanently in another country, and have more than once turned down invitations to do so.

Plural of an Adverb

Donna Zuckerberg, review of V. Liapis, A Commentary on the Rhesus Attributed to Euripides (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), in Classical Review 63.1 (2013) 29-31 (at 30):

Hapax is short for hapax legomenon, whose proper plural is hapax legomena. Some will defend the solecisms above on various grounds and call me a mossbacked linguistic prescriptivist, a charge to which I cheerfully plead guilty.

Newer› ‹Older

He shows how the play's vocabulary choices, particularly its use of extensive hapaces (pp. liii-lv), and its metrics (pp. lxiv-lvii) defy easy grouping with either Euripides' early or late works."Classical battle over Facebook founder's sister," Evening Standard (29 April 2013):

Professor Colin Leach, formerly at Oxford University, whose enthusiastic review is due to be published in the Journal of Classical Teachers later this year, expressed his surprise that Classical Review did not allocate so important a book to a senior academic. He also notes: "Zuckerberg used the 'word' hapaces, which purports to be the plural of hapax. But hapax is not a noun, but an indeclinable adverb, meaning 'once', and hapaces does not exist. It may be a feeble joke, or even an Americanism." God forbid.One might wish that Zuckerberg's hapaces was itself a hapax, but no. See e.g. M. Gwyn Morgan, "The Long Way Round: Tacitus, Histories 1.27," Eranos 92 (1994) 93–101 (at 94, footnote omitted):

Then there is a pause (nec multo post), before his henchman Onomastus appears and delivers the message they have concerted as the indication that all is ready for their coup, a message requiring the use of two hapaces, one—if not both—of them a technical term (ab architecto et redemptoribus).and Pär Sandin, Aeschylus' Supplices: Introduction and Commentary on vv. 1-523 (Lund: Symmachus, 2005), p. 171, n. 469:

To mention only a few hapaces (some recurring in late authors) on -µα, we find Th. 278 ποίφυγµα (on which see Sandin 2001), Th. 523 εἴκασµα, Ag. 396 πρόστριµµα, Ag. 1284 ὑπτίασµα (also Pr. 1005), Ag. 1416 νόµευµα, fr. 79 σκώπευµα.The variant hapakes also occurs, regrettably, e.g. in Martin Bernal, Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization, Vol, III: The Linguistic Evidence (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2006), p. 124:

Szememrényi warns against accepting typological arguments on the ground that oddities or even hapakes (single exceptions) occur in all languages.and Victoria Wohl, Euripides and the Politics of Form (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015), p. 155, n. 8:

Both polupēna and prosthēmata are hapakes that take humble words (the woof of a weaving, pēnē, or the prosaic prosthēkē, appendage) and turn them into unique coinages.More common than either hapaces or hapakes is hapaxes. See e.g. Mark W. Edwards, The Iliad: A Commentary, Vol. V: Books 17-20 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), who uses hapaxes repeatedly on pp. 53-55.

Hapax is short for hapax legomenon, whose proper plural is hapax legomena. Some will defend the solecisms above on various grounds and call me a mossbacked linguistic prescriptivist, a charge to which I cheerfully plead guilty.