Wednesday, November 30, 2022

Something's Missing

Feodor Bronnikov (1827-1902), Consecration of a Herm (Освящение гермы), in Moscow, Tretjakov Gallery (inv. no. 1801; click once or twice to enlarge):

Something's missing — see

Walter Burkert, Structure and History in Greek Mythology and Ritual (1979; rpt. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982 = Sather Classical Lectures, 47), p. 39 (note omitted):

More than two thousand years have done their best to mutilate extant herms and to obliterate what would still today be scandalous in public; but anybody familiar with vase-paintings knows what a classical herm looks like: a rather dignified, usually bearded, head on a four-cornered pillar and, in due place, an unmistakable, realistically molded, erect phallus.

Tuesday, November 29, 2022

Go Away

Sophocles, fragment 201g Radt (tr. Hugh Lloyd-Jones):

Go away! You are disturbing sleep, the healer of sickness.If Valckenaer's conjecture is adopted, the line means:

ἄπελθε· κινεῖς ὕπνον ἰατρὸν νόσου.

ἄπελθε· κινεῖς Nauck: ἄπελθ' ἐκείνης codd. Clem. Alex. Strom. 6.2.10.3 (2, 429, 12 Stählin)

ὕπνον ἰητρὸν codd.: ὕπνος ἰατρὸς Valckenaer

Go away! Sleep is healer of that sickness.I've been sick for the past two days.

Final Examination

Karl Maurer (1948-2015), An Introduction to Robert Frost: A Talk with Notes. Edited by Adam Cooper and Taylor Posey (Asheville: Taylor Posey, Publisher, 2021), p. 102:

The final examination, if there is one, might consist of this: the student must recite to me a long poem chosen by him which he has learnt by heart, and he must then answer (orally, in English) various questions on it; and I would mark him according to the skill and truth of his recitation. and the worth of his answers.

Monday, November 28, 2022

Academic Conferences

Camille Paglia, "Junk Bonds and Corporate Raiders: Academe in the Hour of the Wolf," a

review of David M. Halperin, One Hundred Years of Homosexuality and Other Essays on Greek

Love, and John J. Winkler, The Constraints of Desire: The Anthropology of Sex and

Gender in Ancient Greece, in Arion, 3rd ser., 1.2 (Spring, 1991) 139-212 (at 186-188):

The self-made Inferno of the academic junk-bond era is the conferences, where the din of ambition is as deafening as on the floor of the stock exchange. The huge post-Sixties proliferation of conferences, used as an administrative marketing tool by colleges and universities, produced a diversion of professional energy away from study and toward performance, networking, advertisement, cruising, hustling, glad-handing, back scratching, chitchat, groupthink. Interdisciplinary innovation? Hardly. Real interdisciplinary work is done reading and writing at home and in the library. The conferences teach corporate raiding: academics become lone wolves without loyalty to their own disciplines or institutions; they're always on the trail and on the lookout, ears up for the better job and bigger salary, the next golden fleece or golden parachute. The conferences are all about insider trading and racketeering, jockeying for power by fast-track traveling salesmen pushing their shrink-wrapped product and tooting fancy new commercial slogans. The conferences induce a delusional removal from reality. They mislead fad-followers like Halperin and Winkler into beginning ridiculous statements with "We"—we think, we say, we do this or that. No, we don't; that's you, the teeming conference-hoppers, the plague of locusts and froglets croaking in their tiny pond. In the conferences, a host of Bartleby the Scriveners tippy-toe through showy verbal pirouettes and imagine they're running with the bulls at Pamplona. But the menu, as the chorus chants in Monty Python, is nothing but "Spam, Spam, Spam!" The conferences are lightweight shuttlecock scholarship, where the divorced can trawl for new spouses and where people meet in an airless bubble to confirm each other's false assumptions and certitudes. A new Dunciad is needed to chart the reefs and shoals of this polluted boat-choked race course, where no one ever gets anywhere.Id. (at 201):

Whole careers have gone down the tubes at the conferences. Dozens of prominent academics are approaching the moment of reckoning, when they and everyone else will realize they have wasted the best years of their professional lives on cutesy mini-papers and globe-trotting. By their books ye shall know them. A scholar's real audience is not yet born. A scholar must build for the future, not the present. The profession is addicted to the present, to contemporary figures, contemporary terminology, contemporary concerns. Authentic theory would mean mastery of the complete history of philosophy and aesthetics. What is absurdly called theory today is just a mask for fashion and greed. The conferences are the Alphabet City of addiction to junk, the self-numbing anodyne of rootless, soulless people who have lost contact with their own ethnic traditions. Their work will die with them, for it is based on neither learning nor inspired interpretation. The conferences are oppressive bourgeois forms that enforce a style of affected patter and smarmy whimsy in the speaker and polite chuckles and iron-butt torpor in the audience. Success at the conferences requires a certain kind of physically inert personality, superficially cordial but emotionally dissociated. It's the genteel high Protestant style of the country clubs and corporate board rooms, with their financial reports and marketing presentations. The transient intimacies of the conferences are themselves junk bonds. Dante would classify the conference-hoppers as perverters of intellect, bad guides, sowers of schism.

The conferences have left a paper trail of folly and trivial pursuit. True scholars are time-travelers, not space-travelers.

Attendance at conferences must cease to be defined as professional activity. It should be seen for what it is: prestige-hunting and long-range job-seeking junkets, meat-rack mini-vacations. The phrase "He or she is just a conference-hopper" (cf. "just a gigolo") must enter the academic vocabulary. I look for the day when conference-hopping leads to denial of employment or promotion on the grounds that it is a neglect of professional duties to scholarship and one's institution. Energies have to be reinvested at home. The reform of education will be achieved when we all stay put and cultivate our own garden, instead of gallivanting around the globe like migrating grackles. Furthermore, excessive contact with other academics is toxic to scholarship. Reading and writing academic books and seeing academics every day at work are more than enough exposure to academe. The best thing for scholars is contact with nonacademics, with other ways of thinking and seeing the world.

The Architect of Freedom

Diodorus Siculus 16.90.1 (tr. Robin Waterfield):

A crowd gathered as his body was being taken to the place of burial and the following decree was read out by the herald, Demetrius, who had the most powerful voice of any herald at the time:Waterfield's translation omits τοὺς τυράννους καταλύσας.Timoleon was the architect of freedom for three reasons, not two: "he deposed the tyrants and defeated the barbarians and repopulated the greatest of the Greek cities."It has been decreed by the people of Syracuse that Timoleon the son of Timaenetus is to be buried at a cost of two hundred mnas and is to be honoured in perpetuity with musical, equestrian, and athletic contests, because he defeated the barbarians and repopulated the greatest of the Greek cities, and thereby made himself the architect of freedom for the Siceliots.κατὰ τὴν ἐκφορὰν ἀθροισθέντος τοῦ πλήθους τόδε τὸ ψήφισμα ἀνηγόρευσεν ὁ Δημήτριος ὃς ἦν μεγαλοφωνότατος τῶν τότε κηρύκων·ἐψήφισται ὁ δᾶμος τῶν Συρακοσίων Τιμολέοντα Τιμαινέτου Κορίνθιον τόνδε θάπτειν μὲν ἀπὸ διακοσιᾶν μνᾶν, τιμᾶσθαι δὲ εἰς τὸν ἅπαντα χρόνον ἀγώνεσσι μουσικοῖς καὶ ἱππικοῖς καὶ γυμνικοῖς, ὅτι τοὺς τυράννους καταλύσας καὶ τοὺς βαρβάρους καταπολεμήσας καὶ τὰς μεγίστας τῶν Ἑλληνίδων πόλεων ἀνοικίσας αἴτιος ἐγενήθη τᾶς ἐλευθερίας τοῖς Σικελιώταις.

Labels: typographical and other errors

Rubbish

A.D. Leeman, Orationis Ratio, Vol. I (Amsterdam: Adolf M. Hakkert, 1963), p. 14:

And on the other hand much of what seems rubbish at first sight is not quite so bad if we take the trouble to study it more closely.

Different

Thomas Mann, The Magic Mountain, chapter 5 (tr. James E. Woods):

He asked Hans Castorp why, if he really wanted to read such books, he had not borrowed them from the director, who surely had a fine selection of that sort of literature. But Hans Castorp replied that he wanted to own them himself—it was different reading a book that you owned. And besides, he loved to take his pencil and underline at will. Joachim listened for hours to the sound coming from his cousin's balcony: a paper knife slipping through uncut pages.

Er fragte, warum Hans Castorp sie sich nicht, wenn er dergleichen schon lesen wolle, vom Hofrat geliehen habe, der diese Literatur doch sicher in guter Auswahl besitze. Aber Hans Castorp erwiderte, er wolle sie selber besitzen, es sei ein ganz anderes Lesen, wenn das Buch einem gehöre; auch liebe er es, mit dem Bleistift dareinzufahren und anzustreichen. Stundenlang hörte Joachim in seines Vetters Loge das Geräusch, mit dem das Papiermesser die Blätter broschierter Bogen trennt.

The King of Snoopers and Meddlers

Lucien Febvre (1878-1956), The Problem of Unbelief in the Sixteenth Century: The Religion of Rabelais, tr. Beatrice Gottlieb (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1982), p. 61:

Ioan. Vulteii Rhemi Inscriptionum Libri Duo (Paris: Apud Sim. Colinæum, 1538), p. 6:

Visagier describes Rabella as a curious man whose curiosity makes him utterly unbearable. He might be called the king of snoopers and meddlers. "You want to know everything," Visagier reproves him, "who I am, how I live, who my father is, where I was born and where my house is. You want to know my name and my sweetheart's name, my style of life, what I eat and who works for me, whether I am lucky in love or ever have been. You want to know—" In the next line Visagier's muse gets a little too outspoken for us to quote in translation. But immediately after this digression comes the expected conclusion: "There is nothing that you do not want to know. But in your rage to know all, Rabella, what you want to know is not enough and it is too much (non satis et nimium scire, Rabella, cupis).""A little too outspoken for us to quote in translation" — that's like catnip to me. Here is Jean Visagier's entire poem (Ad Rabellam) in Latin:

Scire cupis qui sim, qui vivam, quoque parenteThe outspoken line is number 8, "Scire cupis quam sit mentula longa mihi," which means "You want to know how long my dick is."

Sim natus, quae sit patria, quique lares.

Scire cupis nomenque meum, nomenque puellae.

Scire cupis vitae quod genus ipse sequar.

Scire cupis mensas, famulus mihi quotque ministret. 5

Scire cupis campi jugera quotque habeam.

Scire cupis quam sim, fuerimque in amore beatus.

Scire cupis quam sit mentula longa mihi.

Nil non scire cupis; sed dum cupis omnia scire,

Non satis et nimium scire, Rabella, cupis. 10

Ioan. Vulteii Rhemi Inscriptionum Libri Duo (Paris: Apud Sim. Colinæum, 1538), p. 6:

A Pack of Humbugs and Quacks

William Makepeace Thackeray, Vanity Fair, chapter 56:

A few years before, he used to be savage, and inveigh against all parsons, scholars, and the like declaring that they were a pack of humbugs, and quacks that weren't fit to get their living but by grinding Latin and Greek, and a set of supercilious dogs that pretended to look down upon British merchants and gentlemen, who could buy up half a hundred of 'em. He would mourn now, in a very solemn manner, that his own education had been neglected, and repeatedly point out, in pompous orations to Georgy, the necessity and excellence of classical acquirements.

Sunday, November 27, 2022

The Dullness of Vergil

A.D. Leeman, Orationis Ratio, Vol. I (Amsterdam: Adolf M. Hakkert, 1963), p. 12:

In fact the only reason why Virgil is thought 'dull' by some of his modern readers is that these readers are too 'dull' in Latin to perceive his subtlety, variety and novelty of expression. We know the conceptual and factual meanings of most Latin words, we even know, with the help of statistics, which words are 'poetic' and which 'unpoetic'; but who among us can claim to feel all the shades of meaning of a Latin word, who can see its whole 'colour', who can taste its full 'flavour'?

Old and New

Tacitus, Annals 11.24.7 (speech of the Emperor Claudius; tr. J.C. Yardley):

Senators, everything that is now believed to be really ancient was once new.

omnia, patres conscripti, quae nunc vetustissima creduntur, nova fuere.

Sit Still and Listen

Homer, Iliad 2.198-206 (he = Odysseus; tr. Richmond Lattimore):

When he saw some man of the people who was shouting,

he would strike at him with his staff, and reprove him also:

"Excellency! Sit still and listen to what others tell you,

to those who are better men than you, you skulker and coward

and thing of no account whatever in battle or council.

Surely not all of us Achaians can be as kings here.

Lordship for many is no good thing. Let there be one ruler,

one king, to whom the son of devious-devising Kronos

gives the sceptre and right of judgment, to watch over his people."

ὃν δ' αὖ δήμου τ᾽ ἄνδρα ἴδοι βοόωντά τ' ἐφεύροι,

τὸν σκήπτρῳ ἐλάσασκεν ὁμοκλήσασκέ τε μύθῳ·

δαιμόνι' ἀτρέμας ἧσο καὶ ἄλλων μῦθον ἄκουε, 200

οἳ σέο φέρτεροί εἰσι, σὺ δ' ἀπτόλεμος καὶ ἄναλκις

οὔτέ ποτ' ἐν πολέμῳ ἐναρίθμιος οὔτ' ἐνὶ βουλῇ·

οὐ μέν πως πάντες βασιλεύσομεν ἐνθάδ' Ἀχαιοί·

οὐκ ἀγαθὸν πολυκοιρανίη· εἷς κοίρανος ἔστω,

εἷς βασιλεύς, ᾧ δῶκε Κρόνου πάϊς ἀγκυλομήτεω 205

σκῆπτρόν τ' ἠδὲ θέμιστας, ἵνά σφισι βουλεύῃσι.

A Sacred Ceremony

Costas Panayotakis, "A Sacred Ceremony in Honour of the Buttocks: Petronius, Satyrica 140.1-11,"

Classical Quarterly 44.2 (1994) 458-467 (at 463):

Therefore, the best reading is the one adopted by Ernout in the Budé edition5 (Paris, 1962): 'pygesiaca sacra' = a sacred ceremony dedicated to πυγή.My brother:

I've seen some buttocks that I'd like to honor.

Saturday, November 26, 2022

I Would Never Read a Book

Sam Bankman-Fried, interview with Adam Fisher (reported here):

"I would never read a book....I'm very skeptical of books. I don't want to say no book is ever worth reading, but I actually do believe something pretty close to that."Charles Dickens, Bleak House, chapter XXI:

"Don't you read, or get read to?"

The old man shakes his head with sharp sly triumph. "No, no. We have never been readers in our family. It don't pay. Stuff. Idleness. Folly. No, no!"

Strength in Numbers

Aristotle, Politics 3.11.2-3 1281a-b (tr. C.D.C. Reeve):

For the many, who are not as individuals excellent men, nevertheless can, when they have come together, be better than the few best people, not individually but collectively, just as feasts to which many contribute are better than feasts provided at one person's expense. For being many, each of them can have some part of virtue and practical wisdom, and when they come together, the multitude is just like a single human being, with many feet, hands, and senses, and so too for their character traits and wisdom. That is why the many are better judges of works of music and of the poets. For one of them judges one part, another another, and all of them the whole thing.

τοὺς γὰρ πολλούς, ὧν ἕκαστός ἐστιν οὐ σπουδαῖος ἀνήρ, ὅμως ἐνδέχεται συνελθόντας εἶναι βελτίους ἐκείνων, οὐχ ὡς ἕκαστον ἀλλ' ὡς σύμπαντας, οἷον τὰ συμφορητὰ δεῖπνα τῶν ἐκ μιᾶς δαπάνης χορηγηθέντων· πολλῶν γὰρ ὄντων ἕκαστον μόριον ἔχειν ἀρετῆς καὶ φρονήσεως, καὶ γίνεσθαι συνελθόντων, ὥσπερ ἕνα ἄνθρωπον τὸ πλῆθος, πολύποδα καὶ πολύχειρα καὶ πολλὰς ἔχοντ' αἰσθήσεις, οὕτω καὶ περὶ τὰ ἤθη καὶ τὴν διάνοιαν. διὸ καὶ κρίνουσιν ἄμεινον οἱ πολλοὶ καὶ τὰ τῆς μουσικῆς ἔργα καὶ τὰ τῶν ποιητῶν· ἄλλοι γὰρ ἄλλο τι μόριον, πάντα δὲ πάντες.

Viaticum

"Sir Simon Towneley, musicologist, bibliophile and popular landowner from a Lancashire Catholic recusant family – obituary," Telegraph (November 25, 2022):

His son Peregrine's eulogy for the funeral Mass ended: "He died fortified by the rites of the Holy Church, and a partridge and a bottle of champagne."Hat tip: Eric Thomson.

All That Is Needed

Lucretius 2.14–36 (tr. A.E. Stallings):

O miserable minds of men! O hearts that cannot see!See the brilliant exposition of these lines in Don Fowler, Lucretius on Atomic Motion: A Commentary on De Rerum Natura, Book Two, Lines 1-332 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), pp. 66-110.

Beset by such great dangers and in such obscurity

You spend your little lot of life! Don't you know it's plain

That all your nature yelps for is a body free from pain,

And, to enjoy pleasure, a mind removed from fear and care?

And so we see the body's needs are altogether spare —

Only the bare minimum to keep suffering at bay,

Yet which can furnish pleasures for us in a wide array.

Nature has no need of more, not golden figurines

Throughout the house, with lamps in their right hands to light the scenes

Of nightly feasts and revelry, nor does nature require

A palace whose enamelled ceiling echoes to the lyre,

Glinting silver and gold, when people can as pleasantly pass

Their hours al fresco, sprawling out in groups on the soft grass

Beside a babbling brook, beneath a tall and shady tree,

Where they can merrily unwind, and practically for free —

Especially on spring days when the weather smiles serene

And when the season sprinkles flowers all across the green.

Nor do raging fevers any faster cease to burn

If you have fancy tapestries on which to toss and turn

And royal-purple sheets to wrap in, than if you are broke

And all you have to huddle under is a peasant's cloak.

o miseras hominum mentes, o pectora caeca!

qualibus in tenebris vitae quantisque periclis 15

degitur hoc aevi quodcumquest! nonne videre

nihil aliud sibi naturam latrare, nisi ut qui

corpore seiunctus dolor absit, mensque fruatur

iucundo sensu cura semota metuque?

ergo corpoream ad naturam pauca videmus 20

esse opus omnino, quae demant cumque dolorem.

delicias quoque uti multas substernere possint

gratius interdum, neque natura ipsa requirit,

si non aurea sunt iuvenum simulacra per aedes

lampadas igniferas manibus retinentia dextris, 25

lumina nocturnis epulis ut suppeditentur,

nec domus argento fulget auroque renidet

nec citharae reboant laqueata aurataque templa,

cum tamen inter se prostrati in gramine molli

propter aquae rivum sub ramis arboris altae 30

non magnis opibus iucunde corpora curant,

praesertim cum tempestas arridet et anni

tempora conspergunt viridantis floribus herbas.

nec calidae citius decedunt corpore febres,

textilibus si in picturis ostroque rubenti 35

iacteris, quam si in plebeia veste cubandum est.

18 mensque Marullus: mente codd.: menti' Lachmann

28 templa codd.: tecta Macrobius 6.4.21

The Unforgivable Sin

Lucien Febvre (1878-1956), The Problem of Unbelief in the Sixteenth Century:

The Religion of Rabelais, tr. Beatrice Gottlieb (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1982), p. 5:

The problem is not (for the historian, at any rate) to catch hold of a man, a writer of the sixteenth century, in isolation from his contemporaries, and, just because a certain passage in his work fits in with the direction of one of our own modes of feeling, to decide that he fits under one of the rubrics we use today for classifying those who do or do not think like us in matters of religion. When dealing with sixteenth-century men and ideas, when dealing with modes of wishing, feeling, thinking, and believing that bear sixteenth-century arms, the problem is to determine what set of precautions to take and what rules to follow in order to avoid the worst of all sins, the sin that cannot be forgiven—anachronism.Id., p. 11:

Can it be that the problems about their views that we have declared to be insoluble have been brought into being by ourselves, and by us alone? Do we not substitute our thought for theirs, and give the words they used meanings that were not in their minds?Id., p. 12:

But to reread the texts with eyes of 1530 or 1540—texts that were written by men of 1530 and 1540 who did not write like us, texts conceived by brains of 1530 and 1540 that did not think like us—that is the difficult thing and, for the historian, the important thing.

Friday, November 25, 2022

Patron of Textual Critics

Richard Tarrant, Texts, editors, and readers: Methods and problems in Latin textual criticism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), p. 166, n. 10:

Pontius Pilatus' quod scripsi, scripsi (John 19.22) could qualify him as the patron of textual critics.

It Will Vex the Kind of People I Don't Like

A.E. Housman, letter to Grant Richards (August 30, 1911):

I am a conservative, and do not like changing anything without due reason.R.W. Chambers, Man's Unconquerable Mind: Studies of English Writers, from Bede to A.E. Housman and W.P. Ker (London: Jonathan Cape, 1939), p. 379:

Housman was no political partisan, yet he generally welcomed a Conservative victory at a bye-election, 'because', he said, 'it will vex the kind of people I don't like'.I owe the references to E. Christian Kopff, "Conservatism and Creativity in A.E. Housman," Modern Age 47.3 (Summer, 2005) 229-238 (at 231, 238).

Thursday, November 24, 2022

Portrait of an Intellectual

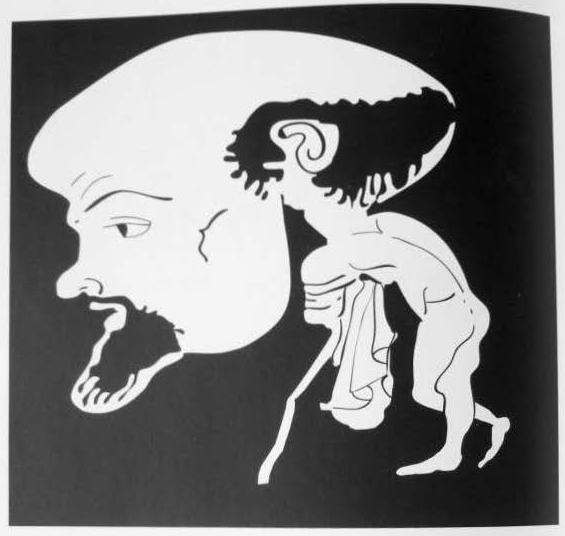

Red-figure askos (Paris, Louvre G 610):

Paul Zanker, The Mask of Socrates: The Image of the Intellectual in Antiquity, tr. Alan Shapiro (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995 = Sather Classical Lectures, 59), p. 33 (note omitted):

On a small red-figure askos, for example, of ca. 440 B.C., a naked, emaciated little man with an enormous head leans far forward on his slender staff and seems to be simply lost in contemplation. Just so, we are told, Socrates could stand still for hours, concentrating on a problem (fig. 20). The vase probably caricatures one of the leading thinkers of the day. The creature's bare skull, swelling out in all directions, seems about to burst with all the profound thoughts churning inside it. He is nevertheless an Athenian citizen, and not a member of one of those categories of inferiors like slaves or barbarians, as we can infer from the characteristic pose of resting on the staff and short mantle.Alexandre G. Mitchell, "Humour in Greek Vase-Painting," Revue Archéologique 37 (2004) 3-32 (at 18, notes omitted):

On one side a bald deformed man leans on a staff; the other side shows a roaring lion. The man’s body is absurdly small compared to his enormous head, larger than the whole body. He is leaning on a staff; his cloak is folded under his left arm and hangs off the staff. This bald man is strikingly caricatured. His attitude is that of many nonchalant strollers at the palaestra. With such a huge head and pensive attitude, this figure could be a caricature of a sophist; not a sophist in particular but what the common artisan in the Potters quarter thought of sophists, who spent their time thinking, or chatting at the palaestra. Views on sophists, or philosophers in antiquity were diverse. In Clouds Aristophanes gives a very critical and comical view of what was probably thought of intellectuals and "wandering wonder-workers" in Athens by most Athenians: "Bah! Good-for-nothings, I know. You're talking about those vagabonds, those pallid faces, those barefooted wanderers"; "lazy, supplied with food for doing nothing"; "who never went to the baths to wash". Socrates himself, in a discussion on the needs of the philosopher, clearly despises the body, while holds in the highest regard the soul. According to D. Metzler the lion is as symbol of hoplite virtue routing out the sophist parasite.There is a drawing of the intellectual based on this vase in Alexandre G. Mitchell, Greek Vase-Painting and the Origins of Visual Humour (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), p. 246, fig. 125: From Eric Thomson via email:

The egg-head's glabrous pate conforms in shape to the rounded convexity of the askos, and what does the banquet parasite do after a skinful but spout? The head is oriented in just that direction. The fact that the askos was originally a wine-skin is a bonus.

Wednesday, November 23, 2022

An Ugly Necessity

G.K. Chesterton, A Short History of England (New York: John Lane Company, 1917), p. 103:

... all government is an ugly necessity ...

Dyscolitis

Hugh Lloyd-Jones, "Ritual and Tragedy," in

Fritz Graf, ed., Ansichten griechischer Rituale. Geburtstags-Symposium für Walter Burkert (Stuttgart: B.G. Teubner, 1998), pp. 271-295 (at 271-272):

During the summer of 1959 the new papyrus of Menander's Dyskolos had just been published. The first edition was obviously inadequate, and the world of scholarship was swept by an epidemic of an illness which Eduard Fraenkel called Dyscolitis. Scholars everywhere were publishing emendations; most of these proved to be identical with the emendations of other scholars, so that Bruno Snell suggested a new siglum, which meant 'omnes praeter Martinum'. I had been commanded by Paul Maas to bring out an edition in the hope of checking this disease. Knowing this, Reinhold Merkelbach sent me a telegram inviting me to come to Germany to lecture on the Dyskolos. This happened during Merkelbach's brief but important time as professor at Erlangen, where he was not far from Karl Meuli and where Burkert had just become a Privatdozent. In order to finance my expedition, he arranged for me to lecture also at Cologne and Würzburg.

This was my first visit to a German-speaking country, and I had scarcely ever spoken German; it was almost as if I had suddenly found myself in a place where I had to speak ancient Greek. My education had owed much to the presence in Oxford of famous exiles from Germany, so that it was an exciting experience for me. I went first to Cologne, where I met Günther Jachmann, Andreas Rumpf, Josef Kroll and Albrecht Dihle. From Erlangen I went to the neighbouring Würzburg, where I met Friedrich Pfister and Rudolf Kassel. In Erlangen itself I met Alfred Heubeck and Walter Burkert. Merkelbach felt that Burkert's teachers in Erlangen had not insisted strongly enough on the importance of textual criticism, so he decided that the three of us should go through the Dyskolos together. On the first day, we got halfway through the play. Burkert explained that on the next day he could not come to the institute; he was about to become a father for the first time, and must remain at home. 'All right!', said Merkelbach, 'then we meet in your house!', and we did meet there and finished the play, poor Frau Burkert sustaining us with an agreeable dish of rhubarb.

A Crude Latin Inscription

An inscription from Sardinia (Meana Sardo, 2nd century AD, Iscrizioni latine della Sardegna I 183), in Italia Epigrafica Digitale, XV: Sardinia (Rome: Dipartimento di Scienze dell’Antichità,

Sapienza Università di Roma, 2017), p. 178, number 188 (click once or twice to enlarge):

Simplified Latin text, followed by my translation:

There is a similar inscription from Pompeii — Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum IV 2360 = Carmina Latina Epigraphica 45. See Attilio Mastino and Raimondo Zucca, "Verpa qui lego," Sicilia Antiqua 13 (2016) 125-131.

The stone:

[vides d]uas berpasberpas = verpas. On verpa see J.N. Adams, The Latin Sexual Vocabulary (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1982; rpt. 1993), pp. 12-14.

[ego sum] tertius qui

lego

You see two pricks.

I, the one reading this, am the third.

There is a similar inscription from Pompeii — Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum IV 2360 = Carmina Latina Epigraphica 45. See Attilio Mastino and Raimondo Zucca, "Verpa qui lego," Sicilia Antiqua 13 (2016) 125-131.

The stone:

Philological Camp Followers

Barry Baldwin, "Editing Petronius: Methods and Examples," Acta Classica 31 (1988) 37-50 (at 37, footnote omitted):

Although arranged in discrete notes on particular passages, this paper is not a random miscellany. It comports a theme both coherent and combative, being in the main a stout plea for pragmatism and conservatism against the popular sports of interpolation-hunting and textual emendation engaged in by latter-day Petronian editors and their philological camp followers. True, I would not fight to the death for every phrase beginning id est or scilicet, nor for every last reading in Η (the Codex Traguriensis). But far more are defensible than is allowed in other quarters, and the burden of proof or probability should be transferred back to those who tamper with the text rather than rest upon the shoulders of those who defend it. Above all, such phantoms as Fraenkel's Carolingian interpolator should be exorcised in favour of level-headed consideration of each and every case on its individual merits.

Tuesday, November 22, 2022

Hair, Skin, Flesh, Bone, Marrow

Stephanie Jamison, "Brāhmaṇa syllable counting, Vedic tvác 'skin', and the Sanskrit expression for the canonical creature," Indo-Iranian Journal 29 (1986) 161-181, 330 (at 172):

I wondered if this particular combination of body parts might occur in curse tablets, but nothing jumped out at me from a quick reading of Henk S. Versnel, "καὶ εἴ τι λ[οιπὸν] τῶν μερ[ῶ]ν [ἔσ]ται τοῦ σώματος ὅλ[ο]υ[.. (... and any other part of the entire body there may be ...) An Essay on Anatomical Curses," in Fritz Graf, ed., Ansichten griechischer Rituale. Geburtstags-Symposium für Walter Burkert (Stuttgart: B.G. Teubner, 1998), pp. 216-267. Versnel did have this amusing sentence on p. 248:

Vedic texts give us almost tediously ample evidence that the five terms found in the MS passage: lóman- 'hair', tvác- 'bone', māṁsá- 'flesh', ásthi- 'bone', and majján- 'marrow', arranged in that particular order, are the fixed traditional expression of the make-up of the canonical beast.See further Calvert Watkins (1933-2013), How to Kill a Dragon: Aspects of Indo-European Poetics (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), pp. 525-536.

I wondered if this particular combination of body parts might occur in curse tablets, but nothing jumped out at me from a quick reading of Henk S. Versnel, "καὶ εἴ τι λ[οιπὸν] τῶν μερ[ῶ]ν [ἔσ]ται τοῦ σώματος ὅλ[ο]υ[.. (... and any other part of the entire body there may be ...) An Essay on Anatomical Curses," in Fritz Graf, ed., Ansichten griechischer Rituale. Geburtstags-Symposium für Walter Burkert (Stuttgart: B.G. Teubner, 1998), pp. 216-267. Versnel did have this amusing sentence on p. 248:

Whoever fancies a beautiful girl or boy and wishes to influence her or his feelings, would be well advised to peruse a few corpora of defixiones or magical papyri.

Blood for Blood

Euripides, Electra 1093-1094, tr. J.H. Kells, "Euripides, Electra 1093-5, and Some Uses of δικάζειν,"

Classical Quarterly 10.1 (May, 1960) 129-134 (at 130):

... one murder is to bring another in its train, decreeing it ...Kells, p. 134:

... ἀμείψεται

φόνον δικάζων φόνος ...

The Greeks were perhaps more inclined to draw imagery from law and the administration of law than we are, because they had an almost romantic passion for law (cf. the wealth of legal reference and imagery in, say, Aeschylus). There is room for further exploration of this tendency.Euripides, Suppliant Women 614 (tr. Edward P. Coleridge):

Vengeance calls vengeance forth; slaughter calls for slaughter.Related post: Forgiving One's Enemies.

δίκα δίκαν δ' ἐκάλεσε καὶ φόνος φόνον.

Epitaph of Lucius Runnius Pollio

Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum XII 5102 = Carmina Latina Epigraphica 188 = Inscriptiones Latinae Selectae 8154 (from Narbonne, now lost; my translation):

Lucius Runnius Pollio, son of Gnaeus, of the Papirian voting tribe.Franz Cumont, After Life in Roman Paganism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1922), p. 54 (footnote omitted):

For this reason I drink to the dregs more greedily (than ever) in my tomb,

because I must sleep and remain here.

L(ucius) Runnius Pap(iria) Cn(aei) f(ilius) Pollio.

[eo] cupidius perpoto in monumento meo,

quod dormiendum et permanendum heic est mihi.

eo vel hoc suppl. Ritschl

An epitaph of Narbonne jokingly expresses the vulgar idea as to the participation of the deceased in the banquet: "I drink and drink again, in this monument," says the dead man, "the more eagerly because I am obliged to sleep and to dwell here."See Maria José Pena, "Sur quelques carmina epigraphica de Narbonnaise," Revue archéologique de Narbonnaise 36 (2003) 425-432 (at 426-427).

Humility

James Henry, Aeneidea, or Critical, Exegetical, and Aesthetical Remarks on the Aeneis, Vol. I (London: Williams and Norgate, 1873), pp. 649-651 (on Vergil, Aeneid 1.381 "sum pius Aeneas"):

Before Christianity, while we were all pagans alike, humility was meanness. No one ever dreamed of depreciating himself either to his God or to his brother man. He that recommended himself to the favor of God, never thought of saying he was unworthy of that favour, never thought of pleading against himself, on the contrary he put forward all his merits, all he had done, all he would do. To have underrated himself was the last thing in the world to occur to his mind, to his common human sense, and the surest way to prevent God from doing that which he might otherwise have been inclined to do, the surest way to foil himself in his object. In his dealings with man he proceeded on the same principle, always on the principle of his merits, always endeavoured to appear as well as he could, to impress every one with the best possible opinion of him, and so be treated in return by every one as an honest, truthspeaking, brave, generous, noble-minded and above all tender-hearted, "pius" (see Rem. on l. 14) man.

The pagan was thus at least consistent, dealt with his God and his brother man on the same principle, always and upon all occasions standing up for, and never unless in some paroxysm of despair, like Oedipus's, turning upon, abusing and depreciating himself. The first Christians, too, were consistent, but their consistency was of an opposite kind. They recommended themselves to the favour of God and man, not on the ground of merit, but on the ground of demerit. The more they sunk themselves, the more they expected to be exalted, the lower down at the table they took their seat, the higher up did they expect to be asked to sit. They washed the beggars' feet, without pomp and without ceremony, in the sure expectation that angels would in return wash their feet, and clothe them with surplices of spotless dazzling white. Humility and want of merit served the same purpose with them as transcendant merit, and a consciousness of it, served amongst the pagans, it was their way to honour among men, and honour with their God, their road to heaven, their "sic itur ad astra." Real humility, a really modest opinion of themselves, was their ladder to glorification, real humility I mean in every respect, except—and it is a startling exception—their religion. It never so much as once entered into their heads to extend their humility to their religion. To their religious pride there were no bounds. Humble and modest in all other respects, they were in respect of their new religion all Jews, as proud, overbearing, and intolerant, as ready to extirpate the Hittite, Gergashite, and Amalekite. With this one exception, however, they were consistent. Humble before heaven, humble towards each other, frugal, simple, self-denying, kind-hearted, and affectionate amongst themselves, ever ready to renounce this world, and all its pomps and pleasures, in order, by so doing, the better to secure for themselves what they called an eternal crown of glory hereafter. But these first Christians have all, long since, gone the way Jew and Pagan went before them, and we have now another Pharoah, who knows not Joseph—a Pharoah who has inherited not the real, living humility, sincerity, and simplicity of his forefathers, but the names, phrases, words, titles, and empty sounds, and who palms these off, in place of the qualities themselves, on all with whom he has dealings, whether terrestrial or celestial, on his brother man, as on God. Your correspondent, therefore, is your dear sir, and you are your correspondent's most obedient, humble servant, at the very moment you are reprimanding or cashiering him. If a police officer, you touch your hat as you are making an arrest; a judge, you weep when you are passing sentence of death; a hangman, you beg pardon of the culprit about whose neck you are putting the rope. Unworthy to stand before your God, you kneel, and from a crimson velvet cushion pour forth your regularly returning tide of devotion, your unmeasured praise of him, your equally unmeasured dispraise of yourself. Your unaffected contrition, humiliation, nothingness; your love, hope, faith, and gratitude, all fresh gushing from your heart every Sunday at least, if not every day of the year, at precisely the same hour, precisely the same moment, or precisely the same spot, unaffected, unstudied, unpremeditated, in the ready cut and dry words of the printed formularies read or intoned for you by a paid substitute.

In Aeneas's introduction of himself to Venus there is none of this paltry double-dealing, of this vile compound of ours, of verbal humility and real pride, of this our so fashionable seasoning of insolence with compliment. Without any even the least prevarication, he presents himself in his real and true character, the character in which he is so often, so invariably, presented to the reader by the author, viz., as Aeneas, the tender-hearted (the gentle knight of chivalrous times), seeking with his Penates, and surviving compatriots, a new land in place of that out of which he had been expelled by a victorious invader.

Meetings

Vergil, Aeneid 1.361-362 (tr. Allen Mandelbaum):

Now there come together

both those who felt fierce hatred for the tyrant

and those who felt harsh fear.

conveniunt quibus aut odium crudele tyranni

aut metus acer erat.

Paean to Health

Ariphron, Paian to Hygieia, tr. William D. Furley and Jan Maarten Bremer, Greek Hymns, Vol. I: The Texts in Translation (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2001), p. 224:

Health, most cherished of gods for men, with youThe Greek, from Furley and Bremer, Vol. II: Greek Texts and Commentary, pp. 175-176:

I pray to live the remainder of my life, and you be kind to me!

If there is any joy in wealth or children

or in kingly power which elevates men to gods, or in desires

which we pursue with all the subterfuge of Aphrodite,

or if the gods grant humans any other pleasures

or relief from miseries,

in your presence, blessed Health,

they thrive and shine, endowed with charm.

But without you no one's life is happy.

Ὑγεία βροτοῖσι πρεσβίστα μακάρων, μετὰ σεῦBesides Furley and Bremer, Vol. I, pp. 224-227, and Vol. II, pp. 175-180, and the works there cited, see now Pauline A. LeVen, The Many-Headed Muse: Tradition and Innovation in Late Classical Greek Lyric Poetry (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), pp. 277-282.

ναίοιμι τὸ λειπόμενον βιοτᾶς, σὺ δέ μοι πρόφρων ξυνείης.

εἰ γάρ τις ἢ πλούτου χάρις ἢ τεκέων

ἢ τᾶς ἰσοδαίμονος ἀνθρώποις βασιληΐδος ἀρχᾶς ἢ πόθων

οὓς κρυφίοις Ἀφροδίτας ἕρκεσιν θηρεύομεν,

ἢ εἴ τις ἄλλα θεόθεν ἀνθρώποισι τέρψις ἢ πόνων

ἀμπνοὰ πέφανται,

μετὰ σεῖο, μάκαιρ' Ὑγίεια,

τέθαλε καὶ λάμπει Χαρίτων ὀάροις.

σέθεν δὲ χωρὶς οὔτις εὐδαίμων ἔφυ.

The Fashion of Today

Memoirs of Mistral. Rendered into English by Constance Elisabeth Maud (London: Edward Arnold, 1907), p. 11:

It was with these nursery rhymes, songs, and tales that our parents in those days taught us the good Provençal tongue. But at present, vanity having got the upper hand in most families, it is with the system of the worthy Monsieur Dumas that children are taught, and little nincompoops are turned out who have no more attachment or root in their country than foundlings, for it's the fashion of to-day to abjure all that belongs to tradition.

Monday, November 21, 2022

Contending Emendations

J.S. Phillimore, "Dogmatic Diviners and Propertius," Classical Review 31.3/4 (May-June, 1917) 86-96 (at 93):

[I]t would be a great mistake to imagine that conjectures serve no good purpose, even when they are demonstrably futile. There is no better means of solving a crucial passage than by clearing and narrowing the issue through the cross-examination of contending emendations. Such discussion has always been the means of rubbing rusty bits of text bright.

I Wish It Were True

Vergil, Aeneid 9.610-611 (tr. J.W. Mackail):

Nor does creeping old age weaken our strength of spirit or abate our force.

nec tarda senectus

debilitat viris animi mutatque vigorem.

610 'sera, in aliis tarda' Servius

Vanished Landscapes

Gustaf Sobin (1935-2005), Ladder of Shadows: Reflecting on Medieval Vestige in Provence and Languedoc (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), pp. 167-168 (notes omitted):

For just as the flora has left its ghostly imprint embedded in so much fossilized matter, so, too, its memory has been sprinkled across the surface of innumerable church cartularies, bullaria, monastic records; been buried within the archival wealth of countless wills and testaments, marriage contracts, notarized deeds; or, occasionally, been inscribed across the surface of cadastral survey maps, outlining the limits of given properties. Within such documents, a stray phytotoponym—an oblique reference, say, to some olive grove offered up as part of a medieval dowry—gives researchers, on occasion, an invaluable aperçu of the floral environment of a particular locale at a given historical moment.

Fagus sylvatica, or common beech, is a perfect example in point. For the expanse that that tree once occupied can still be measured today, either by the lingering presence of ancient place-names in current usage or by the detection of such names in medieval records. In toponymic form, the tree appears under a variety of synonyms: Fage, Fau, Fagette, Fageas, Fayard, and so on. In each and every case, these place-names testify to a vanished environment. Infallibly, they indicate the exact location of forests that—in retracting—have left nothing for memento but their own estranged vocables. Among the many eloquent examples cited by Aline Durand, one in particular—drawn from a medieval cartulary— refers to a certain Faja oscura located in the Causse du Larzac. Faja signifies the tree itself, with all the nutritive oils inherent in its woody fruit, whereas oscura evokes the darkness, and thus the density, of those once-flourishing beeches. Long since converted into pastureland, that arboreal stand endures in a lone microtoponym: Lou Fagals. Mnemonic marker, it designates little more than a tiny ramshackle hamlet in the commune of Les Rives (Hérault).

The word—along with its residual counterpart, the fossil—bears witness to those vanished landscapes. Properly interpreted, its seemingly inconsequential particles, buried in so much somnolent documentation, allow one a glimpse—at least—of that lost ecology. It's as if the word, as a token of human consciousness, had withstood the retraction and ultimate disappearance of that dense sylvatic canopy—that Faja oscura—in order to preserve the wood's very memory. Even more, it serves to preserve our very own. For in that retraction and ultimate disappearance, the interface between culture and nature—cultum and incultum—has vanished as well. Only the word, it would seem, has withstood that spoliation. Having done so, it reminds us of a time in which the woods—the earth itself—hadn't yet been sacrificed, alas, for the sake of ourselves alone.

Labels: arboricide

Epitaph of Philokynegos the Gladiator

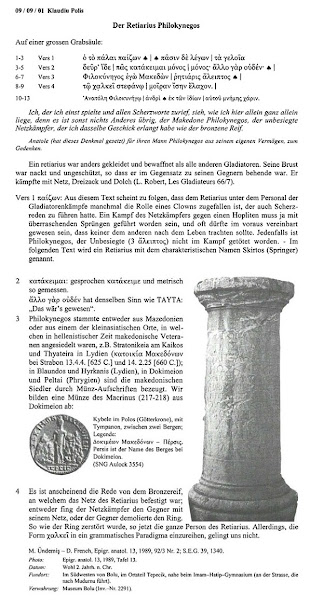

Reinhold Merkelbach and Josef Stauber, Steinepigramme aus dem griechischen Osten, Bd. 2: Die Nordküste Kleinasiens (Marmarasee und Pontos) (Munich: K.G. Saur, 2001), pp. 235-236 (09/09/01, from Claudiopolis in Cilicia, 2nd century AD; click once or twice to enlarge):

Simplified transcription of the Greek, followed by my translation:

Merkelbach and Stauber explain the bronze ring as follows:

ὁ τὸ πάλαι παίζων, πᾶσιν δὲ λέγων τὰ γελοῖαNet fighter = Latin retiarius.

δεῦρ' ἴδε πῶς κατάκειμαι μόνος μόνος· ἄλλο γὰρ οὐδέν·

Φιλοκύνηγος ἐγὼ Μακεδών ῥητιάρις ἄλειπτος

τῷ χαλκεῖ στεφάνῳ μοῖραν ἴσην ἔλαχον.

Ἀνατολὴ Φιλοκυνήγῳ ἀνδρὶ ἐκ τῶν ἰδίων αὐτοῦ μνήμης χάριν.

The one who formerly played and told jokes to everyone,

see how I lie down here alone, alone, for (there is) nothing else;

I, Philokynegos, a Macedonian, undefeated net fighter,

obtained by chance the same fate as the bronze ring.

Anatole (set up this monument for her) husband Philokynegos from his own (funds), in honor of his memory.

Merkelbach and Stauber explain the bronze ring as follows:

Es ist anscheinend die Rede von dem Bronzereif, an welchem das Netz des Retiarius befestigt war; entweder fing der Netzkämpfer den Gegner mit seinem Netz, oder der Gegner demolierte den Ring. So wie der Ring zerstört wurde, so jetzt die ganze Person des Retiarius.I.e.:

The reference is apparently to the bronze ring attached to the net of the net fighter; either the net fighter caught his opponent with his net, or the opponent demolished the ring. As the ring was destroyed, so now the whole person of the net fighter is destroyed.For a joke told by a net fighter, see Roger Dunkle, Gladiators: Violence and Spectacle in Ancient Rome (2008; rpt. London: Routledge, 2013), p. 105 (footnote omitted):

Festus ... quotes a humorous song sung (or recited) by a retiarius to a Gaul (the gladiator type): 'I do not attack you, I attack a fish. Why do you flee me, Gaul?' Festus explains that the murmillo was an offshoot of the Gaul, whose helmet was decorated with the image of a fish.Pauli Festus p. 359 Lindsay:

Retiario pugnanti adversus murmillonem cantatur: "Non te peto, piscem peto, quid me fugis, Galle?" quia murmilionicum genus armaturae Gallicum est, ipsique murmillones ante Galli appellabantur; in quorum galeis piscis effigies inerat.

Place Names

Nicholas Horsfall, "The Poetics of Toponymy," in Fifty Years at the Sibyl's Heels: Selected Papers on Virgil and Rome (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020), pp. 477-486 (at 477):

Names are signposts in a child's imagination and thereafter in an adult's memory: my mental map of childhood London is not a visible map at all, but remains an elaborate tissue of homes, aunts, toyshops, dentists, friends' homes, favourite walks, cinemas. These private gazetteers of ours are perforce idiosyncratic and disorderly; they interrupt unpredictably and inconveniently those slightly more disciplined maps-in-the-mind which we acquire at school, and, if we are very lucky, from parents who read or, better still, recite to us the poetry they love. For that poetry (and all I say is just as true of song) will prove to contain names: 'silent on a peak in Darien', 'down in Demerara', 'at Flores in the Azores', 'silently rowed to the Charlestown shore', which will, many of them, sink into the mire of the not-explained and not-understood, only to emerge, many years on, gleaming, and weighed down with some relevant information.Id., p. 478:

Nor should we neglect the place's very name, viewed not only as a key, but as a real, sounding word; for now, I defy a reader to find beauty or poetic merit in the names Didcot, Casalpusterlengo, Schweinfurth, or Hazebrouck.Id., pp. 481-482:

And it might also be worthwhile to recall, before we consider some more serious aspects of the poetic qualities of toponyms, a brilliant game invented by Paul Jennings:¹⁵ suppose that toponyms were—well, common nouns, then what might they mean? What, after all, might a denver, a houston, a utah actually be, let alone do, once deprived of its capital letter? Naturally, the same game can be played with Italian, German, or French toponyms. The case of the letters leads the reader to concentrate upon letters and sounds, much as in trad. anon.'s 'In Peckham Rye did Alfie Biggs / A stately Hippodrome decree, / where Fred the bread-delivery man' with all due apologies to Coleridge.Related posts:

¹⁵ In Oddly ad Lib (London 1965) 24ff., and in The Jenguin Pennings (Harmondsworth 1963) 15ff.; the parallel invention, of toponyms that become personal names (Oddly ad Lib, 28ff.), is less grandly felicitous.

Sunday, November 20, 2022

One Big Tribe?

Morgan Freeman, 2022 World Cup opening ceremony:

We all gather here in one big tribe.Diogenes of Oenoanda, fragment XXIV, column II, lines 3-11 William = fragment XXX Smith (tr. A.A. Long and D.N. Sedley):

In relation to each segment of the earth different people have different native lands. But in relation to the whole circuit of this world the entire earth is a single native land for everyone, and the world a single home.Donald Richie (1924-2013), The Inland Sea (1971; rpt. Berkeley: Stone Bridge Press, 2002), p. 42:

καθ' ἑκάστην μὲν γὰρ ἀποτομὴν τῆς γῆς ἄλλων ἄλλη πατρίς ἐστιν, κατὰ δὲ τὴν ὅλην περιοχὴν τοῦδε τοῦ κόσμου μία πάντων πατρίς ἐστιν ἡ πᾶσα γῆ καὶ εἷς ὁ κόσμος οἶκος.

"One world" is becoming a hideous possibility and I wish to celebrate our differences for as long as is possible.

Saving Grace

Thomas Mann, The Magic Mountain, chapter 5 (Herr Settembrini speaking; tr. James E. Woods):

"He's an ass, of course, but at least he knows his Latin."

»Er ist zwar ein Esel, aber er versteht wenigstens Latein.«

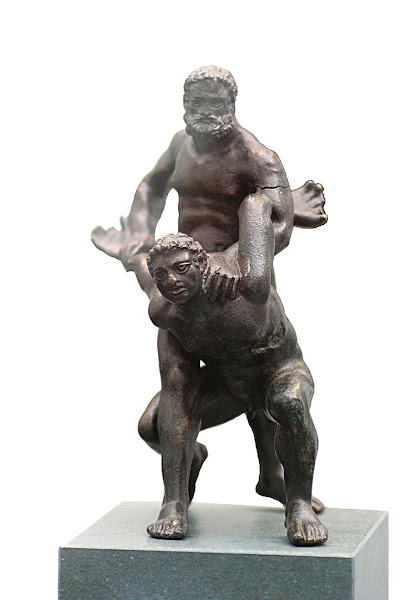

Wrestlers

Andrew Stewart, Art in the Hellenistic World: An Introduction (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), p. 128, figure 70 (click once or twice to enlarge):

Transcription of the caption:

Front view (photograph by Matthias Kabel):

Two wrestlers, small bronze group perhaps from Egypt. Heavier, more experienced, and like a second Herakles (founder of the Olympics), the older man has pinned the younger one's right thigh between his legs and has pulled back his arms prior to throwing him and winning the match. (Although both men's feet touch the ground, only the older one's arc firmly poised.) Perhaps made in the second century, the group was composed and cast in one piece, involving a complex calculation of the disposition of limbs and bodies, considerable anatomical expertise, and rapid pouring of the molten metal so that it reached every corner of the mold before it hardened. H 6 1/2 in. (16.5 cm). Munich, Antikensammlung.The inventory number is SL18.

Front view (photograph by Matthias Kabel):

Double-Edged Arguments

A.R. Burn, Persia and the Greeks: The Defense of the West, 546-478 B.C. (1962; rpt. Minerva Press, 1968), p. 369 (on the Themistocles Decree from Troizen):

In dealing with details the discussion runs into great difficulties; nearly all the arguments are double-edged. If a detail is consistent with Herodotos, it can be used (a) as evidence of genuineness or (b) as ground for suspicion that a forger has used the current tradition; if it is awkward and anomalous, it can nevertheless be used as an argument for genuineness, on the ground that no forger would have done that. If a detail of usage can be shown to be known in the early fifth century by a parallel usage in Aeschylus, it can be suggested that the forger used Aeschylus.

Better Still

Theodore Roosevelt, letter to Frédéric Mistral (December 15, 1904):

Factories and railways are good up to a certain point; but courage and endurance, love of wife and child, love of home and country, love of lover for sweetheart, love of beauty in man's work and in nature, love and emulation of daring and of lofty endeavour, the homely workaday virtues and the heroic virtues—these are better still, and if they are lacking no piled-up riches, no roaring, clanging industrialism, no feverish and many-sided activity shall avail either the individual or the nation.

Saturday, November 19, 2022

Enough Have Been Admitted

Euripides, Ion 721-724 (tr. David Kovacs):

The city would have good reason to keep offGunther Martin ad loc.:

an incursion of strangers.

Enough have been admitted by our old ruler,

King Erechtheus.

στεγομένα γὰρ ἂν πόλις ἔχοι σκῆψιν

ξενικὸν ἐσβολάν·

ἅλις ἔασεν ὁ πάρος ἀρχαγὸς ὢν

Ἐρεχθεὺς ἄναξ.

721 στεγομένα Grégoire: στενομένα L: πενομένα Hermann: στενομέναν Scheidweiler

722 ἐσβολάν L: εἰσβολᾶν Herwerden

post 722 lac. indic. Badham

723 ἅλις ἔασεν Willink: ἁλίσας L: ἅλις ἅλις Heath: ἅλις δ᾿ ἅλις Jerram: ἀλεύσας Diggle

The reconstructions and conjectures that have been made are too optimistic, and their number and diversity discredits them; the thought is still obscure, and the length of the missing section is uncertain. What seems clear is that the chorus explain (γάρ) why they do not want Ion to enter Athens. The previous leader, Erechtheus, features — presumably in a reference to the war against Eumolpus (cf. 277–82n) — together with an arrival of allies (ξενικὸν ἐσβολάν), which makes a suitable parallel with Xuthus and Ion. But both the connection between 721-2 and 723-4 and the way in which the chorus deal with the fact that Xuthus came to the rescue of Athens in the war against Euboea are unclear: Athens’ military situation as described in the play would belie any proud claims of the sufficiency of the autochthonous forces and independence of outside help (cf. the conjecture ἅλις). However, it cannot be excluded that the portrayal of such a delusion was Euripides’ intention.Simms (1983) = Robert M. Simms, "Eumolpos and the Wars of Athens," Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 24 (1983) 197-208. Bob Simms (R.I.P.) was a friend and classmate of mine at the University of Virginia.

721 †στενομένα: Any emendation will fail to convince as long as the construction of the sentence is not known. A form of στένω is difficult to fit into the context: the πόλις is probably Athens, but it is not intelligible why she should wail (middle in Ba. 1372) or be wailed for — ἔχοι σκῆψιν suggests that the city has not reached the point where this would be called for. Whitman (1964) 259 suggests ‘a city which groans at a foreign invasion would have it (sc. invasion) as an excuse’ (sc. for killing Ion). This is hardly comprehensible from the Greek and overlooks that the chorus do not think of Athenians as Ion’s murderers yet. The interpretation as στενοχωρουμένη (‘when a city is in dire straits’; so Wilamowitz) lacks parallels, and this is not a fitting description of Ion’s approach. Grégoire’s στεγομένα would be an odd metaphor: the defensive function of ‘covering’ (cf. Aesch. Sept. 216) is hardly suitable for the pre-emptive curse that demands Ion’s death, nor is the word ever used by Euripides in a military sense.

ἔχοι σκῆψιν: ‘might have (as) a reason/excuse’. ξενικὸν ἐσβολάν may be that reason or part of the action taken as a consequence. The order of the word groups may favour the latter, with an infinitive to be added: Crit. TrGF 43 F 7.10–11 σκῆψιν ... ἔχοντα πρὸς πάτρα̣ν̣ μολεῖν; alternatives for the construction of σκῆψιν ἔχω would be a genitive (Dem. 1.6) or a relative clause (Dem. 54.17, 21) of the consequence, but then the accusative is hard to connect.

722 ξενικὸν ἐσβολάν: ξενικός is not attested elsewhere as being of two terminations, nor is this a common feature of adjectives in -ικός. But if we accept it as feminine, the meaning is probably ‘an assault of foreign allies’; this may be a sarcastic description of Xuthus’ attempt to install his family on the Athenian throne, using the military metaphor to characterise the plan of the ξένος Xuthus (293, 813) as a coup d’état. The meaning and use of ξενικός make it unlikely that this an invasion of foreign enemies, in particular an allusion to the Euboeans: cf. a ξεινικὸς στρατός of mercenaries in Hdt. 1.77.4.

723 ἀρχαγὸς: in Euripides mostly for military leaders: cf. Hipp. 151–2 τὸν Ἐρεχθειδᾶν ἀρχαγόν, τὸν εὐπατρίδαν, Tro. 1267, IT 1303. The chorus may evoke Erechtheus for different purposes: as representative of the pure lineage (that makes foreign influx unnecessary) or as the one who saved Athens in the war against Eumolpus (on which cf. Simms (1983)).

Anacreon Mosaic

Fragmentary 2nd century AD mosaic showing the poet Anacreon, in Autun, Musée Rolin (inv. no. 1563):

Restored, simplified Greek text (from Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum 26:1213):

φέρ' ὕδωρ φέρ' οἶνον ὦ παῖ φερε δ' ἀνθεμόεντας ἡμὶνLines 1-2 = D.L. Page, Poetae Melici Graeci (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1962), p. 198, number 396 = Anacreon, fragment 50 (tr. C.M. Bowra, modified to correspond with the Greek on the mosaic):

στεφάνους, ἔνεικον, ὡς μὴ πρὸς Ἔρωτα πυκταλίσζω.

ὁ μὲν θέλων μάχεσθαι,

πάρεστι γάρ, μαχέσθω.

ἐμοὶ δὲ δὸς προπίνειν

μελιχρὸν οἶνον ὦ παῖ.

Bring water, bring wine, boy, bring garlands of flowers for us, bring them at once, that I may not box with Love.Lines 3-4 = Page, p. 211, number 429 = Anacreon, fragment 84 (tr. C.M. Bowra):

He that wishes to fight,The final two lines were restored, exempli gratia, by Michèle and Alain Blanchard, "La mosaïque d'Anacréon à Autun," Revue des Études Anciennes 75.3-4 (1973) 268-279 (at 275). My translation:

for he may, let him fight.

Give me honey-sweetened wine to drink up, boy.For more on the mosaic, see Patricia A. Rosenmeyer, The Poetics of Imitation: Anacreon and the Anacreontic Tradition (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992), pp. 33-36, with an image of how Anacreon might have looked on p. 21, Plate I(a):

Friday, November 18, 2022

Language and Myth

Stephanie W. Jamison, The Ravenous Hyenas and the Wounded Sun: Myth and Ritual in Ancient

India (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1991), p. 39:

I assume that the language in which a myth is told is an integral part of the telling, not a gauzy verbal garment that can be removed without damage to the real meaning of the myth. The clues to contemporary understanding of myth often lie in its vocabulary and phraseology, which have complex and suggestive relationships with similar vocabulary and phraseology elsewhere. Examining other instances of the same words and phrases will often allow us to see these associations.

I think this is probably true of all mythology: that the verbal expression is of major importance and that abstracting themes or archetypes or patterns from their verbal expression does violence to the 'meaning' of the myth.

Let Us Drink and Have Fun

Inscription on an ossuary which turned up in Aranova, published in

Gian Luca Gregori and Gianmarco Bianchini, "Tra epigrafia, letteratura e filologia. Due inedite meditazioni sulla vita e sulla morte incise sull'ossario di Cresto," in Monique Dondin-Payre and Nicolas Tran, edd., Esclaves et maîtres dans le monde romain.

Expressions épigraphiques de leurs relations (Rome: École française de Rome, 2016), pp. 122-138 (at 125, slightly modified):

Thanks to the friend who pointed out that dum in the first line = "quo puncto temporis (i.q. cum temp.)," citing Thesaurus Linguae Latinae 5,1:2218, especially:

ossarium Chresti, Primigeni, Arescusaes.Photograph of the side of the ossuary containing the inscription (id., p. 126): My translation:

ultuma dum requies fatis me traxerit ad plures,

ubi nemo est, ne lacrumate meos cineres et vos

onerate mero et dicite: homo bellus abit. quod

fuit hoc sumus, quod nunc iacet hoc erimus.

moneo ne lacrumetis: potate, ludite!

spatium breve vitae longum facimus dolore. Fortunae

servimus cum sit Venus et Liber. quod futurum est scit nemo.

hodierna lux ni pereat, bibamus et ludamus! erit dies sine me.

Container of the bones of Crestus, Primigenius, Arescusa.See Dylan Bovet, "Honorare e(s)t onerare," in Michel Aberson et al., edd., Mélanges de linguistique, de philologie et d'histoire ancienne offerts à Rudolf Wachter (Lausanne: Université de Lausanne, 2020 = Cahiers de l'ILSL, 60), pp. 109-116 (at 113-114).

When by the Fates' decree the final rest shall have carried me off to the great majority,

where no one exists, weep not over my ashes, but do you

drench (me) with unmixed wine and say: "A fine fellow has gone away. What

he was, this we are, what now lies here, this we will be."

I urge you not to weep: drink, have fun!

We make life's short span long with grieving. Fortune's

slaves are we, although there is love and wine. What will be, no one knows.

Lest today's light die, let us drink and have fun! There will be day without me.

Thanks to the friend who pointed out that dum in the first line = "quo puncto temporis (i.q. cum temp.)," citing Thesaurus Linguae Latinae 5,1:2218, especially:

VVLG. Tob. 4, 3 dum (Amiat., cum rell.) acceperit deus animam meam, corpus meum sepeli (ἐὰν ἀποθάνω)and also 5,1:2202:

dum introducit actionem momentariam simul accidentem cum actione sententiae regentis (i.q. quo tempore, cum temp. 'als, wann'I revised my translation accordingly.

Admirable Beings

John House, "Renoir and the Earthly Paradise," Oxford Art Journal

8.2 (1985) 21-27 (at 21):

But he felt that the southern landscape was as much the province of the pagan Gods of antiquity as of the Christian God; shortly before he died, Gasquet recorded, he said: 'What admirable beings the Greeks were. Their existence was so happy that they imagined that the Gods came down to earth to find their paradise and to make love. Yes, the earth was the paradise of the Gods . . . This is what I want to paint.'Joachim Gasquet, "Le paradis de Renoir," L'amour de l'art 2.2 (February, 1921) 41 (non vidi):

'Quels êtres admirables que ces Grecs,' disait Renoir quelques jours avant de mourir . . . 'Leur existence était si heureuse qu'ils imaginaient que les dieux, pour trouver leur paradis et aimer, descendaient sur la terre . . . Oui, la terre était le paradis des dieux.' Et il ajoutait: 'Voilà ce que je veux peindre.'

Under Your Command

Lycurgus, Against Lysicles (after the Battle of Chaeronea; tr. Robin Waterfield):

You were general, Lysicles. A thousand of your fellow citizens died and two thousand were taken prisoner. A trophy commemorates our defeat and all Greece has been enslaved. All of these things happened under your command, when you were general—and yet you have the effrontery to live and see the light of day, and even to thrust yourself into the agora, a constant reminder of our country's shame and disgrace.

ἐστρατήγεις, ὦ Λύσικλες, καὶ χιλίων μὲν πολιτῶν τετελευτηκότων, δισχιλίων δ' αἰχμαλώτων γεγονότων, τροπαίου δὲ κατὰ τῆς πόλεως ἑστηκότος, τῆς δ᾽ Ἑλλάδος ἁπάσης δουλευούσης, καὶ τούτων ἁπάντων γεγενημένων σοῦ ἡγουμένου καὶ στρατηγοῦντος τολμᾷς ζῆν καὶ τὸ τοῦ ἡλίου φῶς ὁρᾶν καὶ εἰς τὴν ἀγορὰν ἐμβάλλειν, ὑπόμνημα γεγονὼς αἰσχύνης καὶ ὀνείδους τῇ πατρίδι.

Thursday, November 17, 2022

A Wise Man

Sophocles, Oedipus the King 916 (tr. Richard C. Jebb):

A man of sense judges the new things by the old.

ἔννους τὰ καινὰ τοῖς πάλαι τεκμαίρεται.

Wednesday, November 16, 2022

An Ordered Cosmos

Bertrand Russell (1872-1970), Mysticism and Logic, and Other Essays (London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1919), pp. 60-61:

Mathematics, rightly viewed, possesses not only truth, but supreme beauty—a beauty cold and austere, like that of sculpture, without appeal to any part of our weaker nature, without the gorgeous trappings of painting or music, yet sublimely pure, and capable of a stern perfection such as only the greatest art can show. The true spirit of delight, the exaltation, the sense of being more than man, which is the touchstone of the highest excellence, is to be found in mathematics as surely as in poetry. What is best in mathematics deserves not merely to be learnt as a task, but to be assimilated as a part of daily thought, and brought again and again before the mind with ever-renewed encouragement. Real life is, to most men, a long second-best, a perpetual compromise between the ideal and the possible; but the world of pure reason knows no compromise, no practical limitations, no barrier to the creative activity embodying in splendid edifices the passionate aspiration after the perfect from which all great work springs. Remote from human passions, remote even from the pitiful facts of nature, the generations have gradually created an ordered cosmos, where pure thought can dwell as in its natural home, and where one, at least, of our nobler impulses can escape from the dreary exile of the actual world.

Then and Now

Propertius 4.10.27-30 (tr. H.E. Butler):

Alas! Veii, thou ancient city, thou too wert then a kingdomMax Rothstein ad loc.:

and the throne of gold was set in thy market-place:

now within thy walls is heard the horn of the idle shepherd,

and they reap the cornfields amid thy people's bones.

heu Veii veteres, et vos tum regna fuistis

et vestro posita est aurea sella foro;

nunc intra mures pastoris bucina lenti

cantat, et in vestris ossibus arva metunt.

30 ossibus arva codd.: sedibus arva Phillimore: moenibus arva Giardina: finibus ossa Heyworth

27. So auch Florus I 6, 11 hoc tunc Vei fuere, nunc fuisse quis meminit? quae reliquiae, quod vestigium? laborat annalium fides, ut Veios fuisse credamus.—Properz giebt den Königen des alten Veji die sella aurea, die zuerst Cäsar kurz vor seinem Tode verliehen worden ist.

29. Der pastor lentus, der ruhig und einsam seine Tage hinbringt, bildet den Gegensatz zu dem lebhaft bewegten Treiben, das sich Properz nach dem Beispiel Roms in den Mauern einer Stadt von politischer Bedeutung vorstellt. Die bucina (auch IV 1, 13) als Hirteninstrument Varro rer. rust. II 4, 20 subulcus debet consuefacere, omnia ut faciant ad bucinam.

Classics Curriculum

Eleanor Harding, "Universities are ordered to go woke: Courses from computing to classics are told to 'decolonise' by degrees watchdog and teach about impact of colonialism and 'white supremacy'," Daily Mail (November 16, 2022):

New QAA [Quality Assurance Agency] advice for courses to 'go woke'I have degrees in both computing and classics, but I don't think I could get a degree in any subject today. I wouldn't even make it through freshman orientation.

+ Classic and ancient history

Courses 'must now engage with and explain' the connections between the subject and 'imperialism, colonialism, white supremacy and class division'.

Students should study the work of 'people from oppressed and marginalised groups'.

Teaching should include topics such as 'post-colonial and decolonising approaches' and perspective of groups 'dominated by Empire'.

Modules should also be included on disability, gender and sexuality, bringing out racial, ethnic and other diversities in ancient material.

[....]

+ Computing

Courses should acknowledge and address 'how divisions and hierarchies of colonial value are replicated and reinforced within the computing subject'.

A Syllogism in Some Inscriptions

Werner Peek, Griechische Vers-Inschriften, Vol. I: Grab-Epigramme (Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 1955), p. 320, number 1126 (Eretria, 3rd century BC, simplified text followed by my translation):

Peek, p. 600, number 1941 (from Thisbe, 2nd-3rd century AD):

Pseudo-Epicharmus, in D.L. Page, Further Greek Epigrams (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981), p. 154:

Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum VI 29609 = Carmina Latina Epigraphica 974, followed by my translation:

Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum VI 35887 = Carmina Latina Epigraphica 1532, followed by my translation:

An inscription from Cyrene has recently come to light which is similar to the above. I've combined text (simplified) and translation from Angela Cinalli, "Pseudo-Epicharmean verses in a new inscription from the Necropolis of Cyrene (Tomb S147)," in Francesco Camia et al., edd., Munus Laetitiae. Studi Miscellanei offerti a Maria Letizia Lazzarini (Rome: Sapienza Università Editrice, 2018), Vol. I, pp. 77-92 (at 79), and Federico Favi, "Textual and Exegetical Notes on a New Funerary Inscription from Cyrene," Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 209 (2019) 112–114:

χαῖρε, Διοδώρου Διόγενες, φὺς δίκαιος καὶ εὐσεβής.

εἰ θεός ἐσθ' ἡ γῆ, κἀγὼ θεός εἰμι δικαίως·

ἐκ γῆς γὰρ βλαστὼν γενόμην νεκρός, ἐκ δὲ νεκροῦ γῆ.

Διογένης.

Hail, Diodorus' son Diogenes. You were just and pious.

If the earth is a god, I too am rightly a god;

for, sprung from earth, I became a corpse, and from a corpse, earth.

Diogenes.

Peek, p. 600, number 1941 (from Thisbe, 2nd-3rd century AD):

ἐπὶ ἱερείᾳ Χάροπος.Translation in Andrzej Wypustek, Images of Eternal Beauty in Funerary Verse Inscriptions of the Hellenistic and Greco-Roman Periods (Leiden: Brill, 2013), p. 32:

τύµβος ὁ µυριόκλαυστος, ὁδοιπόρε, τᾶς ἱερείας,

ἇς ὁ τόπος ναῶν ἄξιος, οὐχί τάφων.

εἰ δ' ἄρα τὰν ἀίπαιδα ὁ βάσκανος ἅρπασεν ῞Αιδας,

οὐ µέγα· καὶ µακάρων παῖδας ἔκρυψε κόνις.

ἐνθάδ' ἐγὼ κεῖµαι νεκρὰ κόνις· εἰ δέ κόνις, γῆ·

εἰ δ' ἡ γῆ θεός ἐστι, ἐγὼ θεός, οὐκέτι νεκρά.

For the priestess of Charops.

This tomb, traveller, which many times with tears has been bedewed,

belongs to a priestess; her place worthy of a temple not of a tomb.

If indeed issueless she was snatched by jealous Hades,

it's no great matter; dust also envelops the children of the blessed.

Here I lie, dead, and I am dust; if dust, then the earth.

If earth is a goddess, I am a goddess, and I am not dead.

Pseudo-Epicharmus, in D.L. Page, Further Greek Epigrams (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981), p. 154:

εἰμὶ νεκρός, νεκρὸς δὲ κόπρος, γῆ δ' ἡ κόπρος ἐστίν·Translation by Kathleen Freeman, Ancilla to the Pre-Socratic Philosophers (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1948), p. 40:

εἰ δ' ἡ γῆ θεός ἔστ', οὐ νεκρὸς ἀλλὰ θεός.

I am a corpse. A corpse is dung, and dung is earth.

If Earth is a god, then I am not a corpse but a god.

Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum VI 29609 = Carmina Latina Epigraphica 974, followed by my translation:

invida sors fati rapuisti Vitalem, sanctam puellam,See Peter Kruschwitz, "Five Feet Under: Exhuming the Uses of the Pentameter in Roman Folk Poetry," Tyche: Beiträge zur Alten Geschichte, Papyrologie und Epigraphik 35 (2020) 71-98 (at 92-94).

bis quinos annos, nec patris ac matris es miserata preces.

accepta et cara sueis, mortua hic sita sum.

cinis sum, cinis terra est, terra dea est, ergo ego mortuua non sum.

O hostile chance of Fate, you snatched away Vitalis, an innocent girl,

twice five tears old, and you did not take pity on the prayers of her father and mother.

Pleasing and dear to mine own, I lie here dead.

I am ash, ash is earth, earth is a goddess, therefore I am not dead.

Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum VI 35887 = Carmina Latina Epigraphica 1532, followed by my translation:

cara meis vixi, virgo vitam reddidi,

mortua heic ego sum et sum cinis, is cinis terrast,

sein est terra dea, ego sum dea, mortua non sum.

I lived dear to mine own, I gave up my life while a maiden,

I am dead here and I am ash, this ash is earth,

but if earth is a goddess, I am a goddess, I am not dead.

An inscription from Cyrene has recently come to light which is similar to the above. I've combined text (simplified) and translation from Angela Cinalli, "Pseudo-Epicharmean verses in a new inscription from the Necropolis of Cyrene (Tomb S147)," in Francesco Camia et al., edd., Munus Laetitiae. Studi Miscellanei offerti a Maria Letizia Lazzarini (Rome: Sapienza Università Editrice, 2018), Vol. I, pp. 77-92 (at 79), and Federico Favi, "Textual and Exegetical Notes on a New Funerary Inscription from Cyrene," Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 209 (2019) 112–114:

νεκρὸς ἠμὶ κόπρος· κόπρος δὲ γῆ·

Γῆ δ' ἐστὶ θεός· ἤ τι θέον Γῆ,

καὶ θεὸς δ' ἐστὶ νεκρός.

χαῖρε Φιλησὼ Ἱλρίωνος Lz.

I, a corpse, am dirt. But dirt is earth.

But Earth is god. If Earth is something divine,

then a corpse is god too.

Farewell Phileso daughter of Hilarion, aged seven.

Tuesday, November 15, 2022

Banquet Scene

Paul Zanker and Björn C. Ewald, Living with Myths: The Imagery of Roman Sarcophagi, tr. Julia Slater (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012),

p. 173, illustration 161, followed by the caption:

There is a fuller illustration, showing the lid, in Stine Birk, Depicting the Dead: Self-Representation and Commemoration on Roman Sarcophagi with Portraits (Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, 2013), p. 149, fig. 81, followed by caption:

The deceased lies at table, and four long-haired servants serve him with the best things Nature has to offer. Two women play music to him, and behind him cupids are holding a long garland. Vatican Museums. Around 280.Id., p. 172, with note on p. 275:

The most elaborate of all the known picnic banquet scenes is on a sarcophagus in the Vatican, carved around 280 (Ill. 161).131 The relief—like the kline monuments (p. 29)—shows only one person lying on a couch, who is being pampered and served in the most lavish way. A woman is playing a stringed instrument (pandurium), and behind her another plays the double flute. Four handsome boys with long hair are bringing to the table the best produce the countryside has to offer. Three flying cupids are hanging up a garland and a larger cupid is strewing flowers on the banqueter, just as in Lucian's Elysian Fields. The prepared dishes and the uncooked animals brought along from the countryside (a hare and a peacock) show that nothing is lacking here.The reference is to Rita Amedick, Die antiken Sarkophagreliefs, Band. 1: Sarkophage mit Darstellungen aus dem Menschenleben, Teil 4: Vita Privata (Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag, 1991) (non vidi).

131. Amedick, ASR I 4 (1991), 167 f;, no. 286, plates 15 ff.

There is a fuller illustration, showing the lid, in Stine Birk, Depicting the Dead: Self-Representation and Commemoration on Roman Sarcophagi with Portraits (Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, 2013), p. 149, fig. 81, followed by caption:

The sarcophagus of P. Caecilius Vallianus (cat no. 536). Rome, Musei Vaticani, Museo Gregoriano profano, inv. 9538/9539. Photo: FA-S5718-01.The inscription is Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum XI 3800 (from Isola Farnese / Veii):

D(is) M(anibus) s(acrum) / P(ubli) Caecili / Valliani / a militi(i)s / vixit ann(os) / LXIIIIKatherine M. D. Dunbabin, "The Waiting Servant in Later Roman Art," American Journal of Philology 124.3 (Autumn, 2003) 443-468 (at 450):

Vallianus reclines on his couch in the centre, with the table in front bearing a fish; a woman seated beside him plays a musical instrument, the pandurium. A maidservant with a vessel stands behind her, and on either side youthful male servants (six in all) hurry to serve their master. Three carry huge plates with various delicacies—a cake, a suckling pig, a fowl—a fourth carries the jug and basin used for handwashing; the two at either end bear live animals, a peacock and a hare. Baskets of roses stand at the ends beyond them. All the servants are similar in type, with long hair flowing over their shoulders, smooth cheeks, torques around their necks, soft shoes, and long-sleeved full tunics reaching to their knees.

Nobody Is Happy

Verses by Walther von der Vogelweide (Lachmann number 124, lines 18-24), tr. Philip Wilson, The Bright Rose: Early German Verse 800–1250 (Todmorden: Arc Publications, 2015), page numbers unknown:

Alas, how miserably the young people act

who were once so courteous in all they did.

All they know is sorrow: why is it so?

Nobody is happy no matter where I go.

Dance, laughter, song are all cast down.

Did ever Christian see such a lamentable crowd?

Owê wie jaemerlîche junge liute tuont!

den ê vil hovelîchen ir gemüete stuont,

die kunnen niuwan sorgen: owê wie tuont si sô?

swar ich zer welte kêre, dâ ist nieman frô;

tanzen, lachen, singen zergât mit sorgen gar,

nie kein kristenman gesach sô jaemerlîche schar.

Latinity of the Dark Ages

Gustaf Sobin (1935-2005), Ladder of Shadows: Reflecting on Medieval Vestige in Provence and Languedoc (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), p. 112:

Id., p. 164:

The constraints of one age would provide, ultimately, for the dynamic of the next, but only after those saeculae obscurae had come—mercifully—to a close.Read saecula obscura.

Id., p. 164:

One can safely say that in the tripart division of the natural world as constituted by the Romans—ager for cultivation, saltus for grazing, and silva for woodlands and forest—the first two of these, ager and saltus, would have seriously infringed upon the third—upon silvus, that is—by the end of antiquity.For silvus read silva.

Labels: typographical and other errors

Pious Destruction

Paul MacKendrick, Roman France (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1972), p. 169 (on Sanxay):

From the northeast corner of the baths a vaulted corridor led to a building with nineteen cubicles, perhaps a house of prostitution. Local legend hints that the corridor, when found in the nineteenth century, was adorned with indecent frescoes, piously destroyed by the excavator, a priest.

Monday, November 14, 2022

Goodbye

Epicurus, fragment 70 Usener (tr. A.A. Long and D.N. Sedley):

We should honour rectitude and the virtues and suchlike things if they bring pleasure; but if not, we should say goodbye to them.

τιμητέον τὸ καλὸν καὶ τὰς ἀρετὰς καὶ τοιουτότροπα, ἐὰν ἡδονὴν παρασκευάζῃ· ἐὰν δὲ μὴ παρασκευάζῃ, χαίρειν ἐατέον.

These Boots Are Made for Walking

Berthold Brecht, "Jenny's Song," Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny (tr. H.R. Hays):

As you make your bed you must lieThe same, tr. W.H. Auden and Chester Kallman:

And no one denies it's true