Friday, December 31, 2021

The Virtue of Encouraging Mistrust

John Scheid, Religion, Institutions and Society in Ancient Rome.

Inaugural lecture delivered on Thursday 7 February 2002, tr. Liz Libbrecht (Paris: Collège de France, 2013), § 12:

Twenty-seven years ago Paul Veyne could say that in his day not much Latin was learned. What can we say today? Who could claim that classical languages are alive and well in France and in Europe? In spite of the support that it receives, the teaching of this discipline has been going through difficult times for over two decades. We are compelled to question the demagogic rage consisting in abolishing the study of languages even though they remain indispensable for anyone who has some interest in our historical heritage. And there is no point in maintaining this teaching if it becomes purely superficial or symbolic. Just as is the case for living languages, teaching worthy of the name exists only if the student effectively learns the languages.Id., § 13:

Thirty years ago, historians of Rome could draw on their reading and classical culture to reconstruct the appropriate context for asking the right questions. Once they have lost the ability to use ancient languages, the history of Rome is very likely to resemble medicine in Molière's day.Id., § 25:

This is how ancient history constitutes a science in the making and not a museum of received ideas. By its way of proceeding, it puts out a warning that can be beneficial to all. It highlights the dangers stemming from the impression of familiarity that a culture close to us gives, and denounces the facileness of superficial syntheses. In their daily lives, teachers, researchers and citizens alike operate with general ideas which are often, let's admit, exaggerated or at least approximate, because these are inspired by emotion, ideological choices or even intellectual laziness. From this point of view, ancient history has the virtue of encouraging mistrust, and erudition is assigned a mission that is not limited to filling in footnotes.Id., § 31:

When they practised their religion, the Romans were concerned with neither the survival nor the safety of their soul. They were celebrating rites intended to guarantee the well-being on this earth of the community to which they belonged.

The Final Scene

Cicero, On Old Age 23.85 (tr. William Armistead Falconer):

Again, if we are not going to be immortal, nevertheless, it is desirable for a man to be blotted out at his proper time. For as Nature has marked the bounds of everything else, so she has marked the bounds of life. Moreover, old age is the final scene, as it were, in life's drama, from which we ought to escape when it grows wearisome and, certainly, when we have had our fill.

quod si non sumus immortales futuri, tamen exstingui homini suo tempore optabile est. nam habet natura, ut aliarum omnium rerum, sic vivendi modum. senectus autem aetatis est peractio tamquam fabulae, cuius defetigationem fugere debemus, praesertim adiuncta satietate.

Avoid the Convent

Nathaniel Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, chapter XXIX:

"Should I do wisely, do you think, to exchange this old tower for a cell?"

"What! Turn monk?" exclaimed his friend. "A horrible idea!"

"True," said Donatello, sighing. "Therefore, if at all, I purpose doing it."

"Then think of it no more, for Heaven's sake!" cried the sculptor. "There are a thousand better and more poignant methods of being miserable than that, if to be miserable is what you wish. Nay; I question whether a monk keeps himself up to the intellectual and spiritual height which misery implies. A monk I judge from their sensual physiognomies, which meet me at every turn—is inevitably a beast! Their souls, if they have any to begin with, perish out of them, before their sluggish, swinish existence is half done. Better, a million times, to stand star-gazing on these airy battlements, than to smother your new germ of a higher life in a monkish cell!"

"You make me tremble," said Donatello, "by your bold aspersion of men who have devoted themselves to God's service!"

"They serve neither God nor man, and themselves least of all, though their motives be utterly selfish," replied Kenyon. "Avoid the convent, my dear friend, as you would shun the death of the soul!"

Thursday, December 30, 2021

Development of a New COVID-19 Vaccine?

Willem Joseph Laquy (1738–1798), A Physician or Apothecary Examining a Flask at a Casement (London, Wellcome Collection, accession number 47375i):

Wednesday, December 29, 2021

Reliance on Tradition

Lactantius, Divine Institutes 5.19.3 (tr. Mary Francis McDonald):

If you ask them the plan or purpose of this conviction, they can give none, but they take shelter in the decisions of their ancestors because they were wise, they approved of them, they knew what was best, and they despoil themselves of their senses, swear away from reason, while they believe the errors of others.

a quibus si persuasionis eius rationem requiras, nullam possint reddere, sed ad maiorum iudicia confugiant, quod illi sapientes fuerint, illi probaverint, illi scierint quid esset optimum, seque ipsos sensibus spoliant, ratione abdicant, dum alienis erroribus credunt.

Doctor Estaminetus Crapulosus Pedantissimus

Charles Baudelaire, Intimate Journals, 31 (tr. Christopher Isherwood):

Portrait of the literary rabble.Estaminetus is presumably coined from estaminet, a word of Walloon origin meaning a pub. By pointing this out I mark myself as pedantissimus.

Doctor Estaminetus Crapulosus Pedantissimus. His portrait executed in the manner of Praxiteles.

His pipe.

His opinions.

His Hegelism.

His foulness.

His ideas on art.

His spleen.

His jealousy.

A fine portrait of modern youth.

Portrait de la canaille littéraire.

Doctor Estaminetus Crapulosus Pedantissimus. Son portrait fait à la manière de Praxitèle.

Sa pipe,

ses opinions,

son hégélianisme,

sa crasse,

ses idées en art,

son fiel,

sa jalousie.

Un joli tableau de la jeunesse moderne.

Tuesday, December 28, 2021

How to Eat French Fries

Georges Barral, Five Days in Brussels with Charles Baudelaire, tr. Andrew Rickard (Obolus Press, ©2010), p. 56:

We are barely finished when they place a large earthenware bowl in the middle of the table, spilling over with yellow fried potatoes, crisp and tender at the same time. It is a masterpiece of frying, a rare thing in Belgium.

Baudelaire says they are exquisite. He picks them up slowly with his fingers, one by one, and chews them lightly — the classical method as outlined by Brillat-Savarin. For that matter it is an essentially Parisian gesture, as fried potatoes are a Parisian invention. It is heresy to stab them with a fork.

À peine avons-nous terminé, qu'on met au centre de la table une large écuelle de faïence, toute débordante de pommes de terre frites, blondes, croustillantes et tendres à la fois. Un chef-d'oeuvre de friture, rare en Belgique.

Elles sont exquises, dit Baudelaire, en les croquant lentement, après les avoir prises une à une, délicatement, avec les doigts. C'est la méthode classique indiquée par Brillat-Savarin. D'ailleurs, c'est un geste essentiellement parisien, comme les pommes de terre en friture sont d'invention parisienne. C'est une hérésie que de les piquer avec la fourchette.

Monday, December 27, 2021

While You Live

Inscriptiones Graecae XII, 9 1240, lines 16-21 (tr. Richmond Lattimore):

And through this stele of mine I tell wayfarers while you live, get and enjoy; for all must die.On the phrase κτῶ χρῶ see N. Eda Akyürek Şahin and Hüseyin Uzunoğlu, "Neue Inschriften aus dem Museum von Eskişehir," Gephyra 18 (2019) 137-191 (at 140-142).

καὶ διὰ ταύτης μου τῆς στήλλης μηνύω τοῖς παροδείταις ζῶν κτῶ χρῶ· τὸ γὰρ θανεῖν πᾶσι κέκραται.

Sunday, December 26, 2021

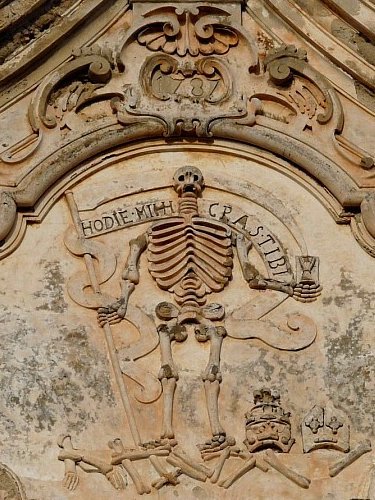

Hodie Mihi, Cras Tibi

Chiesa del Purgatorio, Terracina:

Today for me, tomorrow for thee. Cf. Renzo Tosi, Dizionario delle sentenze latine e greche (Milan: BUR, 2017), # 624 (Mihi heri, et tibi hodie; page number unknown):

La fonte è un versetto del Siracide (38,22), che recita ἐμοὶ ἐχθὲς καί σοὶ σήμερον: l’intero contesto invita a non abbandonarsi alla tristezza quando uno muore, e la frase allude all’ineluttabilità della morte; il motivo è peraltro presente anche negli epitafi epigrafici, e diventa quindi un ammonimento per chi gode delle disgrazie altrui (cfr. Lattimore 256-258), e in particolare in una iscrizione di Fano (CIL 11,6243) che recita: Quod tu es ego fui, quod ego sum et tu eris, «Quel che tu sei, anch’io lo fui, quel che io sono anche tu lo sarai». Una ripresa medievale è in Stephanus de Borbone, Tractatus de diversis materiis praedicabilibus, 1,7,1; nei vecchi cimiteri è molto comune Hodie mihi, cras tibi, il cui perfetto corrispondente Oggi a me domani a te (o viceversa) è ora di uso comune, ma assume una valenza più generica, indicando semplicemente una disgrazia — non necessariamente la morte – che può colpire da un momento all’altro chiunque (cfr. Arthaber 929, Lacerda-Abreu 23, Mota 106): che l’espressione abbia comunemente una valenza più ampia rispetto a quella originaria è osservato già da Alfredo Panzini nel suo Dizionario moderno. Tra le variazioni dialettali segnalo una abruzzese (N’n de ne fa’ habbe de lu mia dulóre, ca quande lu mé é vvécchie, lu té é nnóve), una campana (Ogge chiagne mamma mia, dimane mamma toja) e una friulana (Din don une volte paromp; si veda inoltre Schwamenthal-Straniero 3898); meritano infine di essere segnalati il proverbio brasiliano Quando os meus males forem velhos os de alguem serão novos, un suo equivalente latino (Quid rides me flente? Novum tibi crede futurum luctum, forte meus cum priscus erit, «Perché ridi quando io piango? Sappi che forse quando il mio male sarà vecchio tu ne avrai uno recente»), e una preghiera popolare italiana per le «anime sante» defunte da parte di chi, presto o tardi, sarà come loro.

Saturday, December 25, 2021

Life as an Inn

Cicero, On Old Age 23.84 (tr. William Armistead Falconer):

I do not mean to complain of life as many men, and they learned ones, have often done; nor do I regret that I have lived, since I have so lived that I think I was not born in vain, and I quit life as if it were an inn, not a home. For Nature has given us an hostelry in which to sojourn, not to abide.J.G.F. Powell on tamquam ex hospitio:

non libet enim mihi deplorare vitam, quod multi et ei docti saepe fecerunt, neque me vixisse paenitet, quoniam ita vixi ut non frustra me natum existimem; et ex vita ita discedo tamquam ex hospitio, non tamquam domo; commorandi enim natura devorsorium nobis, non habitandi dedit.

Cf. Sen. Ep. 120.14 nec domum esse hoc corpus sed hospitium, et quidem breve hospitium; ibid. 31.11; 102.24; Apul. Apol. 24 animo hominis extrinsecus in hospitium corporis immigranti; Manii. 4.890; Hadrian fr. 3 (Morel, FPL) animula ... hospes comesque corporis; also [Plut.] Cons. ad Apoll. 117f, life is an ἐπιδημία; ibid. 120b; [Plato], Axiochus 365b; M. Aur. 2.17; Epictetus, Diss. 2.23. For different versions of the image, cf. Tusc. 1.51; 1.118; Hortensius fr. 115 Grilli ex hac in aliam haud paulo meliorem domum ... demigrare; De rep. 6.25; 29; Sen. Ep. 70.16; 65.21; 66.3; Nepos, Att. 22.1; Plato, Phaedo 117 τὴν μετοίκησιν τὴν ἐνθένδε ἐκεῖσε; Apol. 40c; Bion fr. 68 K. (quite unreasonably picked on as the source of Cicero's idea here: see Introd. p. 14 n. 36 and Appendix 2); Favorinus fr. 16 Barigazzi (cf. Introd. p. 28); there is also a similarity with the image of life as a banquet, for which see Brink, Horace on Poetry III, Appendix 20, pp. 444-6.Cf. Bion of Borysthenes, fragment 68 Kindstrand (tr. Edward O'Neil):

"Just as we are ejected from our house," says Bion, "when the landlord, because he has not received his rent, takes away the door, takes away the pottery, stops up the well, in the same way," he says, "am I being ejected from this poor body when Nature, the landlady, takes away my eyes, my ears, my hands, my feet. I am not remaining, but as if leaving a banquet and not at all displeased, so also I leave life: when the hour comes, step on board the ship."

καθάπερ καὶ ἐξ οἰκίας, φησὶν ὁ Βίων, ἐξοικιζόμεθα, ὅταν τὸ ἐνοίκιον ὁ μισθώσας οὐ κομιζόμενος τὴν θύραν ὰφέλῃ, τὸν κέραμον ἀφέλῃ, τὸ φρέαρ ἐγκλείσῃ, οὕτω, φησί, καὶ ἐκ τοῦ σωματίου ἐξοικίζομαι, ὅταν ἡ μισθώσασα φύσις τοὺς ὀφθαλμοὺς ἀφαιρῆται τὰ ὦτα τὰς χεῖρας τοὺς πόδας· οὐχ ὑπομένω, ἀλλ' ὥσπερ ἐκ συμποσίου ἀπαλλάττομαι οὐθὲν δυσχεραίνων, οὕτω καὶ ἐκ τοῦ βίου, ὅταν [ἡ] ὥρα ᾖ, 'ἔμβα πορθμίδος ἕρμα.'

ἕρμα Nauck: ἔρυμα codd.

Agnostos Theos

John Buchan (1875-1940), Greenmantle, chapter 18 (him = John S. Blenkiron, an American):

I could hear him invoking some unknown deity called Holy Mike.

Friday, December 24, 2021

Fire and Apples

Cicero, On Old Age 19.71 (tr. William Armistead Falconer):

Therefore, when the young die I am reminded of a strong flame extinguished by a torrent; but when old men die it is as if a fire had gone out without the use of force and of its own accord, after the fuel had been consumed; and, just as apples when they are green are with difficulty plucked from the tree, but when ripe and mellow fall of themselves, so, with the young, death comes as a result of force, while with the old it is the result of ripeness.J.G.F. Powell ad loc.: Here is the Midrash, from August Wünsche, "Der Midrasch Kohelet und Cicero's Cato Major," Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 3 (1883) 126-128 (at 126-127, with my translation):

itaque adulescentes mihi mori sic videntur ut cum aquae multitudine flammae vis opprimitur, senes autem sic ut cum sua sponte nulla adhibita vi consumptus ignis exstinguitur; et quasi poma ex arboribus cruda si sunt vix evelluntur, si matura et cocta decidunt, sic vitam adulescentibus vis aufert, senibus maturitas.

vix codd. plur.: vi VMO2PaGς

Worin besteht der Unterschied zwischen dem Tode der Jungen und dem Tode der Alten. R. Jehuda und R. Nechemja sind darüber verschiedener Meinung. R. Jehuda sagt: Wenn die Leuchte von selbst erlischt, so ist es gut für sie und für den Docht; wenn die Leuchte aber nicht von selbst erlischt, so ist es nachtheilig für sie und für den Docht. R. Nechemja sagt: Wird die Feige stets zur rechten Zeit gesammelt, so ist es gut für sie und für den Feigenbaum; wird sie aber nicht zur rechten Zeit gesammelt, so ist es nachtheilig für sie und für den Feigenbaum.

What is the difference between the death of the young and the death of the old? R. Yehuda and R. Nechemiah have different opinions about it. R. Yehudah says: If the lamp goes out by itself, it is good for it and for the wick; but if the lamp does not go out by itself, it is disadvantageous to it and to the wick. R. Nechemiah says: If the fig is always gathered at the right time, it is good for it and for the fig tree; but if it is not gathered at the right time, it is disadvantageous to it and to the fig tree.

Thursday, December 23, 2021

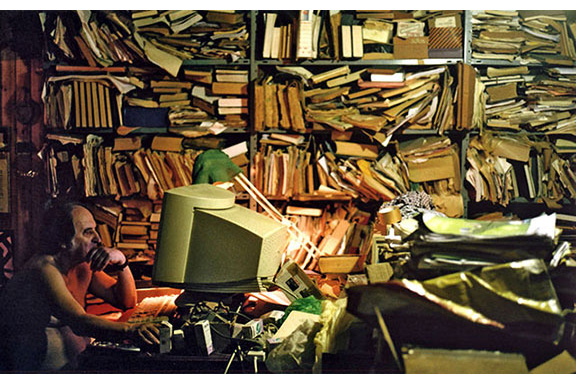

A Scholar's Lair

I sent a friend this picture of Aharon Dolgopolsky with the comment, "He should be reading a book, though, not staring at a computer screen." My friend replied:

Like Borges, I have always imagined Paradise as a kind of library ("Yo, que me figuraba el Paraíso/ Bajo la especie de una biblioteca"), but not this one, with books that look grievously ill-used, housed all higgledy-piggledy in ugly metal shelving. And yes, the plastic box in the centre is an offence to the eye (flat screens are at least book-like) and defeats our pictorial expectations, especially as the scholar seated to the left in profile is a trope; think of Ghirlandaio's and Jan van Eyck's St. Jerome in his Study. Actually, the shirtless Dolgopolsky with his long hair and balding pate does make a convincing Jerome, but it's the Jerome of the desert. This from Giovanni Bellini (Uffizi): Or Lorenzo Lotto (Rome): So your A Scholar's Lair is not far off the mark, though St Jerome in his Garage would do just as well. Lest pot-calling-the-kettle-black should occur to you, attached is a photograph of some of my books in storage:

Wednesday, December 22, 2021

Lucretius Mangled

Image from the beginning of Nietzsche on Theognis of Megara.

A bilingual edition.

Translated by R. M. Kerr, editio electronica (The Nietzsche Channel, MMXV):

Transcription:

The quotation from Lucretius shown above should read as follows (corrections underlined):

The advantage of an electronic, online edition is that it can be easily corrected. God only knows how many mistakes I have made on this blog, which I was able to correct thanks to the sharp eyes of friendly readers.Sic rerum summa novatur

semper, et inter se mortales mutua vivunt.

augescunt aliae gentes, aliae invuntur,

inque brevi spatio mutantur saecla animantum

et quasi cursores vitai lampada tradiunt.

- Lucretius -

- de Rerum Natura, II 75-9 -

The quotation from Lucretius shown above should read as follows (corrections underlined):

Sic rerum summa novatur

semper, et inter se mortales mutua vivunt.

augescunt aliae gentes, aliae minuuntur,

inque brevi spatio mutantur saecla animantum

et quasi cursores vitai lampada tradunt.

Labels: typographical and other errors

We Go All Wrong

Nathaniel Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, chapter XXVI:

And, in truth, while our friend smiled at these wild fables, he sighed in the same breath to think how the once genial earth produces, in every successive generation, fewer flowers than used to gladden the preceding ones. Not that the modes and seeming possibilities of human enjoyment are rarer in our refined and softened era, (on the contrary, they never before were nearly so abundant), but that mankind are getting so far beyond the childhood of their race, that they scorn to be happy any longer. A simple and joyous character can find no place for itself among the sage and sombre figures that would put his unsophisticated cheerfulness to shame. The entire system of Man's affairs, as at present established, is built up purposely to exclude the careless and happy soul. The very children would upbraid the wretched individual who should endeavor to take life and the world as (what we might naturally suppose them meant for) a place and opportunity for enjoyment.

It is the iron rule in our day to require an object and a purpose in life. It makes us all parts of a complicated scheme of progress, which can only result in our arrival at a colder and drearier region than we were born in. It insists upon everybody's adding somewhat (a mite, perhaps, but earned by incessant effort) to an accumulated pile of usefulness, of which the only use will be, to burthen our posterity with even heavier thoughts and more inordinate labour than our own. No life now wanders like an unfettered stream; there is a mill-wheel for the tiniest rivulet to turn. We go all wrong, by too strenuous a resolution to go all right.

Tuesday, December 21, 2021

Wish

Theognis 1153-1154 (tr. J.M. Edmonds):

Be it mine to live rich without evil cares, unharmed, and with no misfortune.

εἴη μοι πλουτοῦντι κακῶν ἀπάτερθε μεριμνέων

ζώειν ἀβλαβέως μηδὲν ἔχοντι κακόν.

The Shame of a Monoglot

Robert A. Kaster, The Appian Way: Ghost Road, Queen of Roads (2012; rpt. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014), p. 54:

Now here I have to confess something of which I am deeply ashamed: I do not speak Italian, in fact I speak no language other than English. Given my line of work, I am in this regard very much an oddity: in a university department of fifteen members, a third of whom have English as their second, third, or even fifth language, I am one of only two monoglots. Yes, I can read academic versions of Italian and a couple of the other modern European languages, for professional reasons, just as I can read ancient Greek and Latin. I can even understand spoken Italian reasonably well, provided it is spoken slowly enough for me to picture the words in written form—hearing as another form of reading, that is to say. But those are passive uses of language. When it comes to taking the spoken language in fluently by ear and sending it back out again by mouth—let's just say I'd have to be twice as good as I am to count as poor.

Monday, December 20, 2021

Foreign Air

Bengt Löfstedt (1931-2004), "On Errors — A Grammarian's Causerie," Acta Classica 17 (1974) 101-104 (at 103):

Outside the ranks of classicists it is, of course, even easier to find people who cannot handle the Latin language. The best comprehensive work we have on historical French syntax is E. Gamillscheg's Historische Französische Syntax (Tübingen 1957). On p. 582 Gamillscheg quotes the following passage from Cicero: Tusculanum et Pompejanum valde me delectant; nisi quod me aere alieno obruerunt, and translates the nisi-clause as follows: 'nur haben sie mich durch eine fremde Luft überfallen'. The use of aes alienum in the sense of 'debt' is perhaps not as well known as might be expected.7Aes alienum literally = another's brass.

7. The example is taken from Cic. Att. 2,1,11, but it is not correctly quoted; the text runs: ... nisi quod me, illum ipsum vindicem aeris alieni, aere non Corinthio sed hoc circumforaneo obruerunt.

Sunday, December 19, 2021

On Hearing a Public Figure Speak

William Shakespeare, King John 2.1.147-148:

What cracker is this same that deafs our earscracker = braggart, boaster

with this abundance of superfluous breath?

Not My Fault

Homer, Iliad 19.86-88 (Agamemnon speaking; tr. A.T. Murray, rev. William F. Wyatt):

But it is not I who am at fault,

but Zeus and Fate and Erinys, that walks in darkness,

since in the place of assembly they cast on my mind fierce blindness...

ἐγὼ δ᾽ οὐκ αἴτιός εἰμι,

ἀλλὰ Ζεὺς καὶ Μοῖρα καὶ ἠεροφοῖτις Ἐρινύς,

οἵ τέ μοι εἰν ἀγορῇ φρεσὶν ἔμβαλον ἄγριον ἄτην...

Saturday, December 18, 2021

Not Required Reading

James Morrison, review of Richard A. Burridge, What are the Gospels? A Comparison with Graeco-Roman Biography (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Pub. Co., 2004), in Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2005.05.31:

It is possible to receive a Ph.D. in Classics today without ever having read the New Testament in Greek.G.P. Goold, "Richard Bentley: A Tercentenary Commemoration," Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 67 (1963) 285-302 (at 296):

The greatest book written in Greek is the New Testament, though a Chinese who studied Greek in the classics departments of Occidental universities might well become an old man without ever discovering the fact.

Political Affiliation

John Buchan (1875-1940), The Thirty-Nine Steps, chapter IV:

I gathered that he had no preference in parties. 'Good chaps in both,' he said cheerfully, 'and plenty of blighters, too.'

Thursday, December 16, 2021

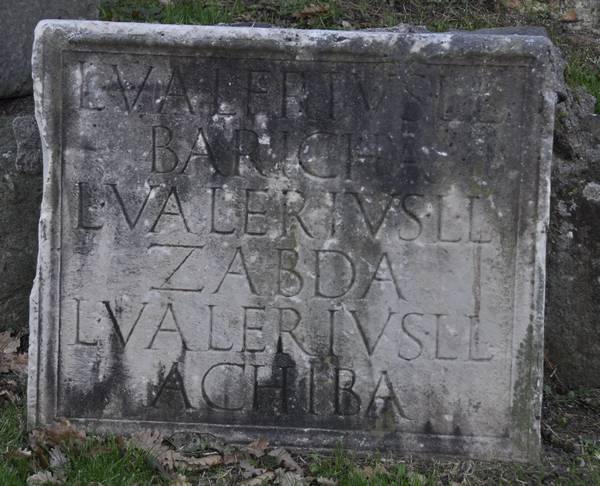

Tomb of Three Freedmen

Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum VI 27959:

L(ucius) Valerius L(uci) l(ibertus) / Baricha / L(ucius) Valerius L(uci) l(ibertus) / Zabda / L(ucius) Valerius L(uci) l(ibertus) / AchibaRobert A. Kaster, The Appian Way: Ghost Road, Queen of Roads (2012; rpt. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014), pp. 43-44:

While some freedmen chose to be interred with their former masters, many arranged for tombs of their own. One of my favorite examples along the Appia is found near the fifth milestone, on the right side of the road as you’re heading away from town. There you will see the core of what used to be a substantial tower tomb, a tall pillar of conglomerate stone perhaps twenty-five feet high, set upon squared blocks of the volcanic tuff that’s plentiful in the area. At the base of the tower is a well-cut inscription on a block of the same stone. The inscription is in the usual all-capitals style, with the raised dots (“interpuncts”) used to separate words: the initial L in the first, third, and fifth lines stands for “Lucius,” a very common Roman first name, and the abbreviation L·L at the end of the same lines stands for “L(ucii) l(ibertus),” “the freedman of Lucius.” Three men, then, who were all once the slaves of a Lucius Valerius and took his name in the usual way, after they were freed. But it’s the names on the second, fourth, and sixth lines that rivet the attention: Baricha, Zabda, and Achiba. Plainly Semitic and probably Jewish, the names all but invite you to imagine a story about their owners, or at least to ask some questions. Were the three men brothers or fellow townsmen before they were taken in slavery? How were they taken? Were they captured when Titus, son of the emperor Vespasian and future emperor himself, sacked Jerusalem in 70 CE, part of the loot that we see soldiers hauling off in the scenes carved on Titus’s arch in the Forum? Or were they brought to Rome still earlier, on a slave dealer’s ship? (Inscriptions like this one are very hard to date: first century CE seems to be the consensus, but nothing can be said beyond that.) Were they among a number of Lucius Valerius’s freedmen buried in the same tomb? Or if so costly a tomb was theirs alone, how did they come to afford it? Had they been business partners in the years after slavery? In fact, might the Lucius Valerius Zabda recalled on this inscription be the same man as the Lucius Valerius Zabda mentioned on another first-century inscription from Rome — a former slave who became a slave dealer in his turn? But the mute stone, as spare and dignified in its own way as the marble plaque on Caecilia Metella’s tomb, provides no answers to satisfy modern curiosity.

Wednesday, December 15, 2021

How Long Would It All Last?

Theognis (?) 773-782 (tr. B.M.W. Knox):

Andrew Robert Burn (1902-1991), Persia and the Greeks: The Defence of the West, c. 546-478 B.C. (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1962; rpt. Minerva Press, 1968), pp. 170-171:

Lord Phoebus, it was you in person who built the towers on our city's high place, as a favour to Pelops' son Alkathoos. Now in person keep the savage army of the Medes away from this city, so that in gladness, when spring comes on, the people may bring you glorious animal sacrifices in procession, rejoicing in the sound of the harp and the lovely banquet, the cries and dance-steps of the hymns in your honour performed at your altar. Save us, I beseech you — for I am terrified when I see the mad folly and the destructive disunion of the Greek people. Be gracious to us, Phoebus, and watch over this our city.The city is Megara.

Φοῖβε ἄναξ, αὐτὸς μὲν ἐπύργωσας πόλιν ἄκρην,

Ἀλκαθόῳ Πέλοπος παιδὶ χαριζόμενος·

αὐτὸς δὲ στρατὸν ὑβριστὴν Μήδων ἀπέρυκε 775

τῆσδε πόλευς, ἵνα σοι λαοὶ ἐν εὐφροσύνῃ

ἦρος ἐπερχομένου κλειτὰς πέμπωσ' ἑκατόμβας

τερπόμενοι κιθάρῃ καὶ ἐρατῇ θαλίῃ

παιάνων τε χοροῖς ἰαχῇσί τε σὸν περὶ βωμόν·

ἦ γὰρ ἔγωγε δέδοικ' ἀφραδίην ἐσορῶν 780

καὶ στάσιν Ἑλλήνων λαοφθόρον. ἀλλὰ σύ, Φοῖβε,

ἵλαος ἡμετέρην τήνδε φύλασσε πόλιν.

Andrew Robert Burn (1902-1991), Persia and the Greeks: The Defence of the West, c. 546-478 B.C. (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1962; rpt. Minerva Press, 1968), pp. 170-171:

Theognis fears for Greece; for the Greek way of life, which he loved, and of which the high tides were marked by those communal festivals of worship, dancing and song, athletics and feasting with the god, on the flesh of the sacrifices; very good to men who had well exercised themselves in dancing or running or wrestling while the huge barbecue was being prepared, and who rarely ate meat on ordinary days. Every human interest was included, from worship to eating (wine was less of a rarity than meat); and all under the brilliant blue sky and among the flowers of an Aegean spring. How long would it all last?

Tuesday, December 14, 2021

Axiomatic

Oliver Taplin, "The Shield of Achilles within the 'Iliad',"

Greece & Rome 27.1 (April, 1980) 1-21 (p. 20, n. 30):

I suspect that it has been axiomatic that any Homeric study which does not take due account of oral composition must be totally valueless: I see no justification for this attitude.

Mediocrity

Charles Baudelaire, The Salon of 1859, I (tr. P.E. Charvet):

Mediocrity has always dominated the scene in every age, that is beyond dispute; but what is also as true as it is distressing is that the reign of mediocrity is stronger than ever, to the point of triumphant obtrusiveness.

Que dans tous les temps la médiocrité ait dominé, cela est indubitable; mais qu'elle règne plus que jamais, qu'elle devienne absolument triomphante et encombrante, c'est ce qui est aussi vrai qu'affligeant.

Mankind

Robert Browning, Luria, Act IV:

But mankind are not pieces—there's your fault!

You cannot push them, and, the first move made,

Lean back to study what the next should be,

In confidence that when 'tis fixed upon,

You'll find just where you left them, blacks and whites:

Men go on moving when your hand's away.

Saturday, December 11, 2021

Givers of Advice

Homer, Iliad 18.312-313 (tr. Peter Green):

On Hektōr, for his bad counsel, they all heaped praise; but none

praised Poulydamas, though he'd offered them excellent advice.

Ἕκτορι μὲν γὰρ ἐπῄνησαν κακὰ μητιόωντι,

Πουλυδάμαντι δ᾽ ἄρ᾽ οὔ τις ὃς ἐσθλὴν φράζετο βουλήν.

Thursday, December 09, 2021

Theory and Practice

Plutarch, Sayings of Spartans: Eudamidas, Son of Archidamus 2 (= Moralia 220 E; tr. Frank Cole Babbitt):

Hearing a philosopher discoursing to the effect that the wise man is the only good general, he said, "The speech is admirable, but the speaker is not to be trusted; for he has never been amid the blare of trumpets."

ἀκούσας δὲ φιλοσόφου διαλεχθέντος ὅτι μόνος ἀγαθὸς στρατηγὸς ὁ σοφός ἐστιν, "ὁ μὲν λόγος" ἔφη "θαυμαστός· ὁ δὲ λέγων ἄπιστος· οὐ γὰρ περισεσάλπιγκται."

Time

Cicero, On Old Age 19.69 (tr. William Armistead Falconer):

Hours and days, and months and years, go by; the past returns no more, and what is to be we cannot know; but whatever the time given us in which to live, we should therewith be content.J.G.F. Powell ad loc.:

horae quidem cedunt et dies et menses et anni, nec praeteritum tempus umquam revertitur nec quid sequatur sciri potest. quod cuique temporis ad vivendum datur, eo debet esse contentus.

horae quidem cedunt Cf. Tusc. 1.76 volat aetas; Ov. Ars am. 3.64; Virg. Georg. 3.284; Sen. Ep. 123.10; Marbod, Lib. dec. cap. 9.75ff.

quod cuique temporis ... contentus That one should be content with one's allotted lifespan is a common moralistic theme, and appears often in consolatory literature. Cf. the next section; Tusc. 1.109 nemo parum diu vivit qui virtutis perfectae perfecto functus est munere; Phil. 2.119; Lucr. 3.931-77 (this is a standard Epicurean theme: see Epicurus, Ep. 3.126; Cic. Fin. 1.63); Sen. Ep. 93.4; 101.15; Marc. 24.1; Benef. 5.17.6; M. Aur. 2.14; 4.50; 12.35 (see below); [Plut.] Cons. ad Apoll. 111a (see below); Milton, Paradise Lost 11.553 (cf. also Sen. Ep. 24.24, quoted on §72).

Wednesday, December 08, 2021

Discordant Affections

Adam Smith (1723-1790), The Theory of Moral Sentiments, ed. Knud Haakonssen (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), pp. 100-101:

Society, however, cannot subsist among those who are at all times ready to hurt and injure one another. The moment that injury begins, the moment that mutual resentment and animosity take place, all the bands of it are broke asunder, and the different members of which it consisted are, as it were, dissipated and scattered abroad by the violence and opposition of their discordant affections.

No Escape

Horace, Satires 2.6.83-97 (tr. Steele Commager):

Seize the path, comrade, believe me. Since all terrestrial creaturesIn line 95, quo ... circa is tmesis of quocirca, and in line 97, aevi brevis is genitive of description (βραχύβιος).

are fated to mortality, and since there is no

escape from death for either great or small, then, good friend,

while it is permitted, live happily among pleasant surroundings;

and live ever mindful of how brief is your span.

carpe viam, mihi crede, comes, terrestria quando

mortalis animas vivunt sortita neque ulla est

aut magno aut parvo leti fuga: quo, bone, circa, 95

dum licet, in rebus iucundis vive beatus,

vive memor, quam sis aevi brevis.

Tuesday, December 07, 2021

Antinous as Silvanus

Relief of Antinous as Silvanus, signed by Antonianus of Aphrodisias, owned by Istituto Bancario

Romano (inv. no. 418 A), on permanent loan to the Palazzo Massimo, Rome (inv. no. 374071):

Rodolfo Lanciani, Wanderings in the Roman Campagna (Boston: Houghlin Mifflin Company, 1909), pp. 185-187:

The latest discovery in connection with this subject was made on the farm of Torre del Padiglione, an estate of eight thousand acres, which the "Società Italiana de' Beni Rustici" has just purchased from the ducal house of the Massimo. This farm is crossed by two highroads, one leading from Lanuvium to Antium, the other from Rome to Satricum. Near their junction, on a knoll which rises some thirty or thirty-five feet above the level of the plain, among the remains of an ancient farmhouse, the bas-relief reproduced on this page was brought to light in October, 1907. The discovery came about by accident, while workmen were digging the earth to plant a vineyard on the southern slope of the knoll. The bas-relief lay face downward on a bed of loose earth, which seemed to have been sifted on purpose to receive and shelter the sculpture. It is not possible that it should have fallen into that position by accident on the occasion of a fire or of an earthquake. It must have been carried to the spot, outside the boundary of the house, and hidden with a purpose, at the time of the first barbarian incursions, by the servants of the house itself. We must not forget that Torre del Padiglione once formed part of the fertile territory of Lanuvium, as favorite a place for summer residence as Tusculum itself, where Antinous and Silvanus had been elected patron saints of the employees of the aristocratic villas, as I shall have occasion to mention again at length in the next chapter.Robert E. A. Palmer, "Silvanus, Sylvester, and the Chair of St. Peter," Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 122.4 (August 18, 1978) 222-247 (at 228, footnote omitted):

The portrait is carved in Pentelic marble, and it is as fresh and perfect as if it had just emerged from the workshop. The god-hero is represented as a young peasant attending to the vintage, the only sign of his apotheosis being a wreath of pine leaves, and the altar with the pine cone. The artist's conception was obviously to represent an Antinous-Silvanus. This artist, this producer of a panel deserving to be placed beside the Palestrina statue, the Mondragone bust, and the Albani bas-relief, has signed his name on the altar: "This is the work of Antonianus from Aphrodisias." These words mean that he belonged to that brotherhood of Greco-Roman sculptors which had opened a studio and a workshop on the Esquiline near the Sette Sale, discovered (and illustrated by Visconti) in 1878. For us, however, the appearance of this divine youth at the Torre del Padiglione, until lately a malarious and deserted spot, bordering on the Pontine district, almost out of reach of civilization, means something more: we take it as an omen of success in the struggle of the present generation against the two great evils of the Campagna, unhealthiness and depopulation. Surely it cannot be a trick of fate that on the day when workmen had been directed to that knoll to try an experiment in vine growing, Antinous should appear in the garb of a sylvan god, attending to the vintage, with bunches of luscious grapes hanging in profusion from his own vines.

On a relief from Torre del Padiglione (Lanuvium) Hadrian's Antinoos is represented as a gorgeous Silvanus, barefoot and clothed, with a dog at his feet. On the altar is a pine cone. In his right hand Antinoos Silvanus holds a pruning hook below a trailing branch of grape leaves and clusters.Hat tip: Eric Thomson.

Nostalgia

Carolyn Kiser Anspach, "Medical Dissertation on Nostalgia by Johannes Hofer, 1688," Bulletin of the Institute of the History of Medicine 2.6 (August, 1934) 376-391 (at 376-377):

The literature of nostalgia, while not voluminous, is of unusual interest and is largely from the pens of Swiss authors. The thesis herewith presented is generally accepted as the earliest publication on the subject, and it is in this work that the term "nostalgia" is first used. The author, Johannes Hofer, was born in Mühlhausen, April 28, 1669, and was graduated from the University of Basel in 1688. He was the author of "De Hydrope Uteri" and of this tractate, which was first published in 1688. It has gone through several editions but has never before been translated. The first reprint of this thesis appeared in 1710, as part of the "Fasciculus Dissertationum Medicarum Selectorium [sic, read Selectiorum]" of Th. Zwinger (Basel). The original title is changed to "De Pothopatridalgia vom Heimwehe." The text is almost identical with that of the first edition, although the term "nostalgia" is replaced throughout by "pothopatridalgia." Zwinger also has introduced an additional case history between the fourth and fifth chapters, has revised and re-arranged parts of the text, and in his twelfth chapter mentions a sweet melody of Switzerland which tends to produce homesickness in everyone who hears it. He actually gives the notes of this "pathologic air," which is called "Kühe-Reyen."Id. (at 380-381, from Anspach's translation of the thesis, § 2):

The reprint of 1745 is identical with the original edition, except that it carries the title, "Dissertatio Curiosa-medica de Nostalgia Vulgo: Heimwehe oder Heimsehnsucht quam in Perantiqua, etc." the remainder of the title being the same as in the first edition. The dissertation is also included in Haller's "Disputationes ad Morborum Historiam," Lausannae, 1757.

The very name presents itself for consideration before all things, which indeed the gifted Helvetians have introduced not long since into their vernacular language, chosen from the grief for the lost charm of the Native Land, which they called das Heimweh; just as those stricken with this disease grieve, either because they are abandoned by the pleasant breeze of their Native Land or because at some time they picture themselves enjoying this more. And hence, since the Helvetians in Gaul (France) were taken often by this mood, among that same nation it merited the name la Maladie du Pays.Kenneth Haynes (via email):

However, it lacks a particular name in medicine, because from no doctor thus far had I learned that it was observed properly or explained carefully. Thus far I had been the first to consider that I should speak more fully concerning it, at the same time that I had first considered it necessary to apply a name. Also I knew just how much they had done all this before me, that it was incumbent upon me to explain certain new phases. Nor in truth, deliberating on a name, did a more suitable one occur to me, defining the thing to be explained, more concisely than the word Nostalgias, Greek in origin and indeed composed of two sounds, the one of which is Nosos [sic, read Nostos], return to the native land; the other, Algos, signifies suffering or grief; so that thus far it is possible from the force of the sound Nostalgia to define the sad mood originating from the desire for the return to one's native land. If nosomanias [sic, read nostimanias] or the name philopatridomania is more pleasing to anyone, in truth denoting a spirit perturbed against holding fast to their native land from any cause whatsoever (denoting) return, it will be entirely approved by me.

Her mistake in giving “Nosos” for “Nostos” (and “nosomanias” for “Nostimanias”) came, I imagine, from a lack of familiarity with the conventions of early modern printed Greek, which include a number of special symbols for ligatures. One of these is the symbol stigma or ϛ (used also for the number six), which represents στ. She must have confused it with the very similar symbol for final sigma, ς. (A couple of ligatures regularly give this kind of trouble because they look like something more familiar — I have often seen the ligature for ευ mistranscribed as ου.)

Labels: typographical and other errors

I'll Take My Stand

Homer, Iliad 18.306-309 (Hector speaking about Achilles; tr. Richmond Lattimore):

I for my part

will not run from him out of the sorrowful battle, but rather

stand fast, to see if he wins the great glory, or if I can win it.

The war god is impartial. Before now he has killed the killer.

οὔ μιν ἔγωγε

φεύξομαι ἐκ πολέμοιο δυσηχέος, ἀλλὰ μάλ᾽ ἄντην

στήσομαι, ἤ κε φέρῃσι μέγα κράτος, ἦ κε φεροίμην.

ξυνὸς Ἐνυάλιος· καί τε κτανέοντα κατέκτα.

Monday, December 06, 2021

Topsy-Turvy

Plutarch, Sayings of Spartans: Agis, Son of Archidamus 17 (= Moralia 216 B-C; tr. Frank Cole Babbitt):

When one of the elderly men said to him in his old age, inasmuch as he saw the good old customs falling into desuetude, and other mischievous practices creeping in, that for this reason everything was getting to be topsy-turvy in Sparta, Agis said humorously, "Things are then but following a logical course if that is what is happening; for when I was a boy, I used to hear from my father that everything was topsy-turvy among them; and my father said that, when he was a boy, his father had said this to him; so nobody ought to be surprised if conditions later are worse than those earlier, but rather to wonder if they grow better or remain approximately the same."

φήσαντος δέ τινος τῶν πρεσβυτέρων πρὸς αὐτὸν γηραιὸν ὄντα, ἐπειδὴ τὰ ἀρχαῖα νόμιμα ἐκλυόμενα ἑώρα ἄλλα δὲ παρεισδυόμενα μοχθηρά, διότι τὰ ἄνω κάτω ἤδη γίγνεται ἐν τῇ Σπάρτῃ, παίζων εἶπε, "κατὰ λόγον οὕτω προβαίνει τὰ πράγματα, εἰ τοῦτο γίνεται· καὶ γὰρ ἐγὼ παῖς ὢν ἤκουον παρὰ τοῦ πατρός, ὅτι τὰ ἄνω κάτω γέγονε παρ᾽ αὐτοῖς· ἔφη δὲ καὶ τὸν πατέρα αὐτῷ παιδὶ ὄντι τοῦτο εἰρηκέναι· ὥστε οὐ χρὴ θαυμάζειν, εἰ χείρω τὰ μετὰ ταῦτα τῶν προτέρων, ἀλλ᾽ εἴ που βελτίω καὶ παραπλήσια γένοιτο."

Sunday, December 05, 2021

Tree Hugger

Nathaniel Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, chapter VIII:

In a sudden rapture, he embraced the trunk of a sturdy tree, and seemed to imagine it a creature worthy of affection and capable of a tender response; he clasped it closely in his arms, as a Faun might have clasped the warm feminine grace of the Nymph, whom antiquity supposed to dwell within that rough, encircling rind.Related post: Tree Huggers.

Silvanus

Relief of Silvanus, in the Capitoline Museum (photograph by Jean-Pol Grandmont; click once or twice to enlarge):

Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum VI 3712 = VI 31180 (my translation):

Sacred to Silvanus and to the Genius of the Imperial Horse Guard. Marcus Ulpius Fructus, sacristan, dedicated the statue plus the base.Robert Turcan, Religion romaine (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1988 = Iconography of Religions XVII, 1), pp. 37-38:

Silvano sacr(um) / et Gen(io) eq(uitum) sing(ularium) Aug(usti) / M(arcus) Ulp(ius) / Fructus / aeditimus / signum / cum ba/se d(e)d(icavit)

Relief en marbre trouvé à Rome sur l'Esquilin; actuellement au Pal. dei Conservatori. Datable du IIe siècle ap. J.-C. Dimensions: 0,80 x 0,45 m.On Silvanus see Peter F. Dorcey, The Cult of Silvanus: A Study in Roman Folk Religion (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1992 = Columbia Studies in the Classical Tradition, 20). On the Imperial Horse Guard see Michael P. Speidel, Riding for Caesar: The Roman Emperors' Horse Guard (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1994).P. E. Visconti, in Bull. Com., 2, 1874, p. 182 ss., pl. XIX; Jones, Cons., p. 254, n° 1, pl. 100; CIL, VI, 3712 = 31180.Stèle à fronton portant la dédicace: SILVANO.SACR / ET GEN(io). EQ(uitum). SING(ularium). AVG(usti). A l'intérieur du cadre plat, Silvain couronné de pin, nu (sauf une peau de bête accrochée sur l'épaule droite et chargée de fruits), chaussé de bottines rustiques, figure debout de face. De la main gauche, il tient une branche de pin, de la main droite une falx coudée à angle droit. A ses pieds, on identifie un chien à gauche, un autel allumé à droite. Dans le champ du relief, on déchiffre l'inscription: M.VLPI(us)/ FRVCTVS/ AEDI/ TI-MVS/ SIGNV-M/ CVM- BA/ SE / D(onum) D(edit). Le monument est consacré à Silvain en même temps qu'au Génie des Equites singulares (dont la caserne se trouvait à quelque 300 m. du lieu de la découverte), car le dieu des bois était très populaire dans ce corps recruté surtout en Pannonie. Le dédicant, gardien d'un temple dont on ignore l'emplacement, peut-être ancien cavalier des corps auxiliaires, doté par Trajan (M. Ulpius) de la citoyenneté romaine, porte un surnom (Fructus) qui a sans doute un rapport avec le dieu de la végétation et de la fructification.

Blood

William Makepeace Thackeray, Vanity Fair, chapter XXXIV (James Crawley speaking):

"Oh, as for that," said Jim, "there's nothing like old blood; no, dammy, nothing like it. I'm none of your Radicals. I know what it is to be a gentleman, dammy. See the chaps in a boat-race; look at the fellers in a fight; aye, look at a dawg killing rats,—which is it wins? the good-blooded ones."Id.:

"Blood's the word," said James, gulping the ruby fluid down. "Nothing like blood, sir, in hosses, dawgs, and men."

Saturday, December 04, 2021

Hatred and Anger

Adam Smith (1723-1790), The Theory of Moral Sentiments, ed. Knud Haakonssen (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), p. 46:

Hatred and anger are the greatest poison to the happiness of a good mind. There is, in the very feeling of those passions, something harsh, jarring, and convulsive, something that tears and distracts the breast, and is altogether destructive of that composure and tranquillity of mind which is so necessary to happiness, and which is best promoted by the contrary passions of gratitude and love.

A Drunken Butterfly

Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum II 2146 (from Porcuna, Spain = Roman Obulco, 1st or early 2nd century A.D., now in the Museo Arqueológico de Porcuna, inv. no. 45; tr. Eric Thomson):

See Javier del Hoyo, Concepción Fernández, and Rocío Carande, "Papilio Ebrius Volitans," Exemplaria Classica 10 (2006) 113-126, 505-506 (at 113-122), with the following Spanish translation on p. 122:

Marcus Porcius, son of Marcus … I also command my heirs to sprinkle my ashes with wine, in order that my inebriated spirit might flutter over it like a butterfly. May grass and flowers cover my bones. If someone halts before the inscription of my name, let him say 'may that which was left by the voracious fire, which, once the body was released, turned itself into ashes, rest peacefully.'Images of the stone: For papilio meaning soul of a dead person see the Oxford Latin Dictionary, sense 2, which cites only this inscription. Cf. Greek ψυχή in Liddell-Scott-Jones, sense VI: "butterfly or moth, Arist. HA 551a14, Thphr. HP 2.4.4, Plu. 2.636c."

M(arcus) Porcius M(arci) --- / heredibus mando etiam cinere ut m[eo vina subspargant ut super eum] / volitet meus ebrius papilio ipsa ossa tegant he[rba et flores] / si quis titulum ad mei nominis astiterit dicat [id quod reliquit] / avidus ignis quod corpore resoluto se vertit in fa[villam bene quiescat].

See Javier del Hoyo, Concepción Fernández, and Rocío Carande, "Papilio Ebrius Volitans," Exemplaria Classica 10 (2006) 113-126, 505-506 (at 113-122), with the following Spanish translation on p. 122:

Marco Porcio, hijo de Marco... Ordeno también a los herederos que rocíen con vino mis cenizas, para que sobre él revolotee (como mariposa) mi espíritu ebrio. Que las hierbas cubran mis huesos. Si alguien se detiene ante el epitafio de mi nombre, diga: aquello que dejó el voraz fuego que — una vez disuelto el cuerpo — lo transformó en pavesas, descanse felizmente.See also Concepción Fernández Martínez, Carmina Latina Epigraphica de La Bética Romana. Las Primeras Piedras de Nuestra Poesía (Sevilla: Universidad de Sevilla, 2007), pp. 220-224 (nº J15).

Friday, December 03, 2021

Bad Company

Adam Smith (1723-1790), The Theory of Moral Sentiments, ed. Knud Haakonssen (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), p. 41:

It is for a reason of the same kind, that a certain reserve is necessary when we talk of our own friends, our own studies, our own professions. All these are objects which we cannot expect should interest our companions in the same degree in which they interest us. And it is for want of this reserve, that the one half of mankind make bad company to the other. A philosopher is company to a philosopher only; the member of a club, to his own little knot of companions.

A Little Respite

Homer, Iliad 11.801 = 16.43 = 18.201 (tr. Richmond Lattimore):

There is little breathing space in the fighting.The same (tr. Peter Green):

ὀλίγη δέ τ᾽ ἀνάπνευσις πολέμοιο.

Too brief is the breathing space from battle.But cf. Claude Brügger on 16.43:

according to MAZON [transl.] ‘to catch one’s breath requires only a short time in war’ (similarly LA ROCHE on 11.801 [transl.]: ‘respite in war is brief, i.e. it need not be long’; FAESI and AH on 11.801 [transl.]: ‘even a short rest is at least a rest’). The expression has a proverbial character (DE JONG, loc. cit.). Gnomic statements frequently serve to underline items of advice (STENGER 2004, 6–9). Typical in such cases is: (a) laconic phrasing via a nominal clause, cf. 630 (LARDINOIS 2001, 99 with n. 32; abstract verbal nouns are particularly suitable: JONES 1973, 14 f.), (b) picking up the verb via a noun with a related stem: ἀναπνεύσωσι – ἀνάπνευσις (LARDINOIS 1997, 218; in general, PORZIG 1942, 31 ff.), and (c) the position of the gnome at (or near) the end of the speech (1.218n.; AHRENS 1937, 23, 52; LOHMANN 1970, 24, 66 f., 72; STENGER loc. cit. 9).

Thursday, December 02, 2021

On Maclou's Return

John Jay Chapman, "Song After Ronsard ('Fais rafraichir mon vin')," Songs and Poems (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1919), p. 7:

Sink the wine within the spring,I don't have access to the relevant volume of Paul Laumonier's edition of Ronsard, so I was glad to come across a very useful edition of Ronsard's Ode 2.10 (or 2.11) by Florence Bonifay (Université Lumière Lyon 2), which surprised me on account of the large number of apparently authorial variants:

And cool it deep and long:

Send Jeanne to me, and let her bring

Her lute, to chant a song.

Three shall dance and one shall sing,

Call Barbe, that in the whirl

Her heavy tresses she may fling

Like a mad Tuscan girl.

See! the sun has dipped his head,

We may not live till morning;

Fill my cup, boy, till the bead

Run over with no warning.

Curse the dolt that slaves to get,

Curse doctor and divine;

My wits were never sober yet

Till they were washed with wine!

Les quatre premiers livres des Odes de Pierre de Ronsard, Vandomois. Ensemble son Bocage. A Paris. Chez Guillaume Cavellart libraire juré de l’université de Paris, demeurant devant le College de Cambrai, a la poulle grasse. 1550. Avec privilege du Roi.Here is another translation of Ronsard's ode, by Edna Worthley Underwood, Songs from the Plains (Boston: Sherman, French & Company, 1917), p. 116:

Source : Pierre de Ronsard, Œuvres complètes I, éd. Laumonier, Droz, Paris, 1931, pp. 207-208. Ré-éditions :- Les quatre premiers livres des Odes de 1553 et de 1555.

- dans les Œuvres de 1560, 1567, 1571, 1673, 1578, 1584, 1587.

→ toutes les variantes sont reportées ici.DU RETOUR DE MACLOU DE LA HAIEA SON PAGE1ODE II, XI

Fai refreschir le vin2, de sorte

Qu’il passe en froideur le glaçon3

Page, & que Marguerite apporte4

Son luc pour dire une chançon5,

Nous ballerons tous trois au son, 5

Et di à Cassandre qu’el’ vienne6

Les cheveus tors à la façon

D’une follatre Italienne.

Ne sen-tu que le jour se passe7

Et tu ne te vas point hastant8 ? 10

Qu’on verse du vin en ma tasse,

A qui le boirai-je d’autant ?

Pour ce jourdui je suis contant

Q’un homme plus fol ne se treuve,

Aiant reveu celui que tant9 15

J’ai conneu seur ami d’épreuve10.

1 1578-1587 : sans titre. Comme la désignation de Maclou, introduite au vers 15 dans les versions de 1555 à 1573, disparaît également à partir de 1578 il n’est désormais plus question de Maclou de la Haye.

2 1578, v. 1 : « Refraischy moy le vin » ; 1584-1587 : « Fay refraischir mon vin »

3 1555-1573 et 1584-1587, v. 2 : « Qu’il passe en froideur un glaçon » 1578, v. 2 : « Qu’il soit aussi froid qu’un glaçon : »

4 1578-1587, v. 3 : « Fay venir Janne, qu’elle apporte »

5 1567-1587, v. 4 : « Son Luth pour dire une chanson »

6 1553-1573, v. 6 : « Et dis à Jane qu’elle vienne »

1578-1587, v. 6 : « Et dy à Barbe qu’elle vienne »

7 1567-1573, v. 9 : « Vois-tu comme le jour se passe »

8 1567-1573, v. 10 : « Et ton pié tu ne vas hastant ? »

9 1555-1573, v. 14-15 : « Qu’un autre plus fol ne se treuve / Revoiant mon Maclou »

10 1578-1587, vv. 9-16 : « Ne vois-tu que le jour se passe ? / Je ne vy point au lendemain : / Page, reverse dans ma tasse, / Remply moy ce verre (84-87 Que ce grand verre soit) tout plain. / Maudit soit qui languit en vain : / Les Philosophes (84-87 Ces vieux Medecins) je n’appreuve : / Le (84-87 Mon) cerveau n’est jamais bien sain, / Que l’Amour & le vin n’abreuve (84-87 Si beaucoup de vin ne l’abreuve) »

Make haste and put the wine to cool,Related post: An Ode by Ronsard.

Let ice and snow no colder be!

Ho — Page! Bid Margot bring her stool

And lute and sing to thee and me,

Or we'll foot it here right royally!

Do thou bid Jane to hasten then,

Her twisted hair piled gracefully

À la a sportive Italienne.

Carest thou not that the day's a-wing?

Why dost thou not make haste, I pray?

Fill full my glass! Begin! — begin —

To whom else should I drink, I say?

I am content that this one day

Should find no folly passing mine,

When my Maclou comes home to stay

No man has truer friend than mine.

Wednesday, December 01, 2021

My Scraps and Rags of Greek

John Jay Chapman, letter to Leonard L. Mackall (January 20, 1924), in "A Sampling of Letters and Obiter Dicta," Arion 2.2/3 (Spring, 1992 - Fall, 1993) 33-65 (at 42-43):

I shall let these heathen rage furiously and imagine a vain thing, and meantime I have been keeping up my scraps and rags of Greek — which I have on ice for the last stage of slippered pantaloon. The consolation is that nobody knows Greek. Those who devote their entire time to it have a further insight — no doubt than the triflers like myself. But they get entrapped in grammatical and psychological questions. It's a grand fairy land. Homer is the easiest — and yet you will find that no one knows the exact meaning of any word in Homer — e.g., Here's a word that means either "very early in the morning" or else "raise high in air." So all the words — and most picturesque they are — describing effects of light or sound mean — darkly gleaming, or brightly blazing, a flame or a spark — or O hang it — something about fire and brightness — plain enough. They are only explained by each other — and occur nowhere else than in Homer, so you must read the whole Iliad for a hint on any one of them. So of the word expressing irritation, wrath, rage, annoyance. It's perfectly plain that some fellow is displeased — but just to what extent nobody knows. That's the charm of Homer. The classic Greeks didn't understand exactly and often made up sham Homeric words to suit the text (as they thought). But I get more out of him every time I read — the fluency and enormousness being the main point and in the later cantos the tragic glory. I don't want to let go of it, and whenever there's a lull in my occupations or I feel désoeuvré, I plunge for a week or a day....Psalms 2.1 (KJV):

Why do the heathen rage, and the people imagine a vain thing?William Shakespeare, As You Like It 2.7.157-158:

The sixth age shifts / Into the lean and slippered pantaloon...Greek ἠέριος = with early morn, or high in air.

This Dear, Dear Land

William Shakespeare, Richard II, Act II, Scene 1, lines 57-60:

This land of such dear souls, this dear, dear land,pelting = paltry, petty

Dear for her reputation through the world,

Is now leased out — I die pronouncing it —

Like to a tenement or pelting farm.

The Buzzard and the Hawk

A fable by John of Schepey, in Ben Edwin Perry, Babrius and Phaedrus (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1965), pp. 562-563 (Appendix, number 644):

I don't have access to Perry's Aesopica, but I found the original in Léopold Hervieux, Les fabulistes latins, IV: Études de Cheriton et ses dérivés (Paris: Didot, 1896), pp. 437-438:

Newer› ‹Older

A buzzard put one of her eggs in a hawk's nest, and the hawk hatched it and nursed the buzzard chick along with her own brood. The hawk's nestlings cast their excrements outside the nest, but the buzzard's chick befouled it. On seeing this, the hawk asked, "Which one of you is it that befouls the nest like this?" And they all answered, "Not I." Finally, after further investigation, the hawk's young ones found it necessary, in self defence, to reveal the truth, and they said, pointing to the young buzzard, "It's that one with the big head." On learning this, the hawk in great indignation seized the young buzzard by the head and threw him out of the nest, saying, " I managed to bring you up from the egg, but I couldn't get you beyond your nature." For, as Horace says, Naturam expellas furca, tamen usque recurret.—TMI Q432.1.TMI = Stith Thompson, Motif-Index of Folk-Literature.

I don't have access to Perry's Aesopica, but I found the original in Léopold Hervieux, Les fabulistes latins, IV: Études de Cheriton et ses dérivés (Paris: Didot, 1896), pp. 437-438:

Busardus proiecit in nidum Accipitris ouum suum. Accipiter autem, credens ouum suum esse, cubauit super illud una cum ouis suis, et creatus (est) inde pullus quem nutriuit Accipiter tanquam suum. Pulli vero Accipitris proiecerunt fimum suum extra nidum; pullus maculauit nidum. Quod aduertens, Accipiter ait: Quis vestrum est qui sic maculat nidum suum? Et omnes dixerunt: Non ego, domine. Tandem facta pleniori inquisicione, oportebat eos pro sui liberacione prodere veritatem, et dixerunt: Domine, iste est cum magno capite, ostenso filio Busardi. Quem Accipiter, cum magna indignacione, per capud arripiens, proiecit extra nidum, dicens: De ouo te produxi; extra naturam non potui.De nobis fabula.

Quia, vt dicit Oratius (1):Naturam expellas furta (sic); tamen vsque recurret.(1) Ép., I, x, 24.