Monday, January 31, 2022

Classical Poetry

Clive James, Collected Poems 1958-2015 (New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2016), pp. 561-562 (note on his lyrics to the song "Femme Fatale" — music by Pete Atkin):

The 'weeping fields' are Virgil's lugentes campos. Perhaps the best translation of the phrase was by the old scholar J.W. Mackail: 'the broken-hearted fields'. While at Cambridge I taught myself quite a lot of classical poetry. The circumstances were ideal: there were undergraduates all over the place who had been through the English public schools and could tell you where the best bits of poetry were in the acres of text. In the New Hall annexe where my wife and I had our first apartment, there was a young graduate student from New Zealand who would put her finger right on the indispensable passages in Homer and get me to recite until I could make a fair fist of the metre: sometimes, I learned, the way the rhythm worked was half the point of the line. Disciplinarians might have frowned at the shortcut but we rarely enjoy seeing someone acquire, just from love, the knowledge that was imparted to us at the point of a cane.Hat tip: John O'Toole.

Sunday, January 30, 2022

Writing

Augustine, On the Trinity 3, Prologue 1 (tr. Edmund Hill):

I must also acknowledge, incidentally, that by writing I have myself learned much that I did not know.

egoque ipse multa quae nesciebam scribendo me didicisse confitear.

Cast Away Care

Anonymous, from Academy of Compliments (1671), in The Oxford Book of Seventeenth Century Verse (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1934), p. 898 (number 584; line numbers added):

Hang sorrow, cast away care,My notes:

Come let us drink up our Sack;

They say it is good,

To cherish the blood,

And eke to strengthen the Back; 5

'Tis wine that makes the thoughts aspire,

And fills the body with heat,

Besides 'tis good,

If well understood,

To fit a man for the Feat: 10

Then call,

And drink up all,

The Drawer is ready to fill,

A pox of care,

What need we to spare, 15

My Father hath made his Will.

10 the Feat = sexual intercourse

15 Drawer = servant who pours the wine

Saturday, January 29, 2022

Shortest Lecture Ever?

Richard Cobb (1917-1996), "Jack Gallagher in Oxford," People and Places (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985), pp. 1-10 (at 3):

Nothing gave Jack greater pleasure than for a solemn occasion to go wrong and for pomposity to trip up in its own robes. One of the stories most often repeated from his extensive Cambridge lore—and our sister University, in Jack's accounts, always appeared much more accident-prone than the apparently staider institution further west—concerned the Inaugural Lecture of a newly-elected Regius Professor of Moral Theology. The Professor, led in to the Senate House, preceded by the beadles, reached the dais, pronounced the single word 'I' and then fell down dead drunk. Jack returned to this account again and again with loving detail.Id. (at 7):

Jack had a healthy dislike for puritans, the politically convicted, radicals, revolutionaries, fanatics, ranters, and ravers. He distrusted legislation, believed that nothing could ever be solved by laying down rules to meet hypothetical situations, and hated theorists and generalizers.

Let's Stop Whining

Aristophanes, Knights 11-12 (tr. Alan H. Sommerstein):

Why are we just lamenting? Oughtn't we to look for some way

to safety, instead of going on and on wailing?

τί κινυρόμεθ᾽ ἄλλως; οὐκ ἐχρῆν ζητεῖν τινα

σωτηρίαν νῷν, ἀλλὰ μὴ κλάειν ἔτι;

Friday, January 28, 2022

Disputing with the Devil

Martin Luther, Table Talk, number 469 (Spring, 1533; tr. Theodore G. Tappert):

Almost every night when I wake up the devil is there and wants to dispute with me. I have come to this conclusion: When the argument that the Christian is without the law and above the law doesn't help, I instantly chase him away with a fart.

Singulis noctibus fere, wenn ich erwach, so ist der Teuffel da und will an mich mit dem disputirn; da habe ich das erfarn: Wenn das argumentum nit hilfft, quod christianus est sine lege et supra legem, so weyse man yhn flugs mit eim furtz ab.

From Liberty to Slavery

Plato, Republic 8.564a (tr. Paul Shorey):

"And so the probable outcome of too much freedom is only too much slavery in the individual and the state."

"Yes, that is probable."

"Probably, then, tyranny develops out of no other constitution than democracy—from the height of liberty, I take it, the fiercest extreme of servitude."

"That is reasonable," he said.

ἡ γὰρ ἄγαν ἐλευθερία ἔοικεν οὐκ εἰς ἄλλο τι ἢ εἰς ἄγαν δουλείαν μεταβάλλειν καὶ ἰδιώτῃ καὶ πόλει.

εἰκὸς γάρ.

εἰκότως τοίνυν, εἶπον, οὐκ ἐξ ἄλλης πολιτείας τυραννὶς καθίσταται ἢ ἐκ δημοκρατίας, ἐξ οἶμαι τῆς ἀκροτάτης ἐλευθερίας δουλεία πλείστη τε καὶ ἀγριωτάτη.

ἔχει γάρ, ἔφη, λόγον.

Thursday, January 27, 2022

Aristophanes, Knights 69-70

Aristophanes, Knights 69-70 (a slave speaking):

πατούμενοιThe Knights of Aristophanes Acted at the Lenaean Festival B.C. 424 Translated into Corresponding Metres by Benjamin Bickley Rogers (London: G. Bell and Sons, Ltd., 1920), p. 7:

ὑπὸ τοῦ γέροντος ὀκταπλάσιον χέζομεν.

We're sure to catch it thrice as bad from master.Aristophanes, The Eleven Comedies. Literally & Completely Translated from the Greek Tongue into English with Translator's Foreword, an Introduction to each Comedy & Elucidatory Notes (New York: Horace Liveright, n.d.), vol. I, pp. 14-15:

[T]he old man tramples on us and makes us spew forth all our body contains.The Comedies of Aristophanes, Vol. 2: Knights edited and translated with notes by Alan H. Sommerstein (Warminster: Aris & Phillips Ltd, 1981), p. 17:

[W]e get worked over by the old man and produce eight times as much by the back passage.Aristophanes, Acharnians. Knights. Edited and Translated by Jeffrey Henderson (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998), p. 237:

The master will pound on us till we shit out eight times as much.Literally:

Trampled on by the old man we shit eightfold.

Tuesday, January 25, 2022

Personification of the People

Aristophanes, Knights 40-43 (one slave speaking to another; tr. Jeffrey Henderson):

We two have a master with a farmer's temperament, a bean chewer, prickly in the extreme, known as Mr. Demos of Pnyx Hill, a cranky, half-deaf little codger.Pliny, Natural History 35.69 (on the painter Parrhasius; tr. H. Rackham):

νῷν γάρ ἐστι δεσπότης

ἄγροικος ὀργὴν κυαμοτρὼξ ἀκράχολος,

Δῆμος πυκνίτης, δύσκολον γερόντιον

ὑπόκωφον.

His picture of the People of Athens also shows ingenuity in treating the subject, since he displayed them as fickle, choleric, unjust and variable, but also placable and merciful and compassionate, boastful <and . . . . >, lofty and humble, fierce and timid—and all these at the same time.

pinxit demon Atheniensium argumento quoque ingenioso. ostendebat namque varium iracundum iniustum inconstantem, eundem exorabilem clementem misericordem; gloriosum < . . . . > excelsum humilem, ferocem fugacemque et omnia pariter.

inconstantem codd.: incontinentem Otto Jahn

lacunam indic. Mayhoff

Monday, January 24, 2022

Bad News

Paul, 2 Corinthians 5.17 (KJV):

Old things are passed away; behold, all things are become new.

τὰ ἀρχαῖα παρῆλθεν, ἰδοὺ γέγονεν καινά.

The City Protects Us

Sophocles, Antigone 182-191 (Creon speaking; tr. H.D.F. Kitto):

And if any holdsJ.C. Kamerbeek on lines 189-190:

A friend of more account than his own city,

I scorn him; for if I should see destruction

Threatening the safety of my citizens,

I would not hold my peace, nor would I count

That man my friend who was my country's foe,

Zeus be my witness. For be sure of this:

It is the city that protects us all;

She bears us through the storm; only when she

Rides safe and sound can we make loyal friends.

This I believe, and thus will I maintain

Our city's greatness.

καὶ μεῖζον ὅστις ἀντὶ τῆς αὑτοῦ πάτρας

φίλον νομίζει, τοῦτον οὐδαμοῦ λέγω.

ἐγὼ γάρ, ἴστω Ζεὺς ὁ πάνθ᾽ ὁρῶν ἀεί,

οὔτ᾽ ἂν σιωπήσαιμι τὴν ἄτην ὁρῶν 185

στείχουσαν ἀστοῖς ἀντὶ τῆς σωτηρίας,

οὔτ᾽ ἂν φίλον ποτ᾽ ἄνδρα δυσμενῆ χθονὸς

θείμην ἐμαυτῷ, τοῦτο γιγνώσκων ὅτι

ἥδ᾽ ἐστὶν ἡ σῴζουσα καὶ ταύτης ἔπι

πλέοντες ὀρθῆς τοὺς φίλους ποιούμεθα. 190

τοιοῖσδ᾽ ἐγὼ νόμοισι τήνδ᾽ αὔξω πόλιν.

There is much in these words that reminds us of Thuc. II 60.2, 3 ἐγὼ γὰρ ἡγοῦμαι πόλιν πλείω ξύμπασαν ὀρθουμένην ὠφελεῖν τοὺς ἰδιώτας ἢ καθ' ἕκαστον τῶν πολιτῶν εὐπραγοῦσαν, ἁθρόαν δὲ σφαλλομένην κτλ.. Cf. also Democr. fr. 252 D.-K. πόλις γὰρ εὖ ἀγομένη μεγίστη ὄρθωσίς ἐστι, καὶ ἐν τούτῳ πάντα ἔνι, καὶ τούτου σῳζομένου πάντα σῴζεται καὶ τούτου διαφθειρομένου τὰ πάντα διαφθείρεται. Possibly Thuc. II 4θ.4 οὐ γὰρ πάσχοντες εὖ, ἀλλὰ δρῶντες κτώμεθα τοὺς φίλους has a certain relevancy to the meaning of τοὺς φίλους ποιούμεθα. The welfare of the state is the conditio sine qua non for the welfare of its citizens and the latter for establishing friendships. This implies that the making of real friends is only possible in connection with the welfare of the city and that enemies of the state never can become 'our' friends.

Sunday, January 23, 2022

Why Should Not We All Be Merry?

Anonymous, from Catch that Catch Can (1658), in The Oxford Book of Seventeenth Century Verse (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1934), p. 810 (number 538, vi):

David Teniers the Younger, Tavern Scene (1658), in the

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

(accession number 1975.77.1)

Why should not we all be merry,

Our Ale is as brown as a Berry?

What then should be the thing,

Should hinder us to sing

Hey down, derry down derry,

Hey down a down hey down derry.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

(accession number 1975.77.1)

The Smell of Christ

Tom Holland, Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World (New York: Basic Books, 2019), p. 151, with note on p. 553:

In an age when there existed no surer marker of wealth than to be freshly bathed and scented, Paulinus hailed the stench of the unwashed as 'the smell of Christ'.23But Paulinus, in the passage cited, seems to be talking about bad breath, rather than about the body odor of the unwashed. See the translation of P.G. Walsh:

23. Ibid. [Paulinus, Letters] 22.2.

The appearance, disposition, and smell of such monks cause nausea in people for whom the odour of death is as the odour of life, who regard the bitter as sweet, the chaste as foul, the holy as hateful. So it is right that we should pay them back, that their smell should be to us the odour of death, so that we do not cease to be the odour of Christ. For why should they who regard our odour as lethal be rightly angry with us if in turn their odour of life stinks in our nostrils? Marracinus finds my fasting distasteful; I cannot bear his drunkenness. He avoids the breath of a monk when he speaks; I avoid the breath of a belching Thraso. If my dry throat displeases him, I loathe his overloaded gullet. If my parched abstention annoys him, the gluttony of his belly annoys me. So I pray for visitors who are not drunk in the early morning but rather are still fasting at evening, who are not blown up with yesterday’s wine but rather are abstemious with today's, who are not crazily tottering through the drunkenness of lust but rather are healthily impaired with virtuous vigils and are drunk with sobriety, men who stagger not because of overindulgence but rather because of a meagre diet.Related posts:

Saturday, January 22, 2022

Ambition

Andrew Robert Burn (1902-1991), Persia and the Greeks: The Defence of the West, c. 546-478 B.C. (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1962; rpt. Minerva Press, 1968), p. 260:

Political events in early fifth-century Athens were chiefly the expression of the rivalries of prominent men and families. Ambition, in men born to greatness, was a proper feeling: 'Ever to be the noblest and superior to others' was a Homeric ideal.7 It is only after centuries of Christianity, or at least lip-service to Christianity, that this lust after the power and the glory has to be veiled, at least from the public eye, behind a programme of service; even at its most naked, expressed in such a saying as 'I believe that I can save this nation and that no one else can'. To a pagan Greek or Roman, the desire to be the best or noblest (aristeuein, a word devoid of moral connotation) was well expressed in the desire to shine in athletics, 'for', to cite Homer again, 'a man has no truer glory than that which he wins with his own feet and hands';8 and even in Greek feeling about athletics in this age, there is a sense of triumph over the defeated rival which is to us repulsive. Pindar twice reminds us of the shame of defeated wrestlers, slinking home, 'avoiding their enemies', as an ingredient in the joy of the victor.9 Sportsmanship, like humility, is a Christian virtue.

7 Il. vi, 208; xi, 784; etc.

8 Od. viii, 147f.

9 Ol. viii, 67/89ff, Pyth. viii, 81/116ff.

Cruel and Wicked

Herman Melville (1819-1891), White-Jacket, Chapter XXXII ("A Dish of Dunderfunk"):

"Well, sir, what now?" said the Lieutenant of the Deck, advancing.I was born and raised Down East, but I never heard the phrase "cruel nice," so far as I can recall. On the other hand, I often heard and uttered the analogous phrase "wicked good."

"They stole it, sir; all my nice dunderfunk, sir; they did, sir," whined the Down Easter, ruefully holding up his pan. "Stole your dunderfunk! what's that?"

"Dunderfunk, sir, dunderfunk; a cruel nice dish as ever man put into him."

"Speak out, sir; what's the matter?"

"My dunderfunk, sir—as elegant a dish of dunderfunk as you ever see, sir—they stole it, sir!"

Friday, January 21, 2022

Not Made of Wood or Stone

Walter Scott (1771-1832), Guy Mannering, chapter VI:

These things did not pass without notice and censure. We are not made of wood or stone, and the things which connect themselves with our hearts and habits cannot, like bark or lichen, be rent away without our missing them.

Truth

Sophocles, Antigone 1195 (tr. R.C. Jebb):

Truth is ever best.Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve, Syntax of Classical Greek from Homer to Demosthenes, First Part: The Syntax of the Simple Sentence, Embracing the Doctrine of the Moods and Tenses (New York: American Book Company, 1900), pp. 57-58 (at 57), § 126:

ὀρθὸν ἁλήθει᾽ ἀεί.

The neuter singular adjective is often used as the substantive predicate of a masculine or feminine subject, whether singular or plural.

Thursday, January 20, 2022

Oracles

Gustave Flaubert, Bouvard and Pécuchet, chapter 8 (tr. A.J. Krailsheimer):

The priest related still more astonishing stories. A missionary once saw Brahmins walking across a vault head downwards, the Grand Lama of Tibet strains his bowels open to give oracles.Related posts:

'Are you joking?' said the doctor.

'Not at all!'

'Come on now, that's a tall story!'

L'abbé rapporta des histoires plus étonnantes. Un missionnaire a vu des brahmanes parcourir une voûte la tête en bas, le Grand-Lama au Thibet se fend les boyaux, pour rendre des oracles.

—Plaisantez-vous? dit le médecin.

—Nullement.

—Allons donc! Quelle farce!

Labels: noctes scatologicae

Wednesday, January 19, 2022

A Mishmash

Plato, Laws 3.692e-693a (tr. Trevor J. Saunders):

If it hadn't been for the joint determination of the Athenians and the Spartans to resist the slavery that threatened them, we should have by now virtually a complete mixture of the races — Greek with Greek, Greek with barbarian, and barbarian with Greek. We can see a parallel in the nations whom the Persians lord it over today: they have been split up and then horribly jumbled together again into the scattered communities in which they now live.

ἀλλ᾽ εἰ μὴ τό τε Ἀθηναίων καὶ τὸ Λακεδαιμονίων κοινῇ διανόημα ἤμυνεν τὴν ἐπιοῦσαν δουλείαν, σχεδὸν ἂν ἤδη πάντ᾽ ἦν μεμειγμένα τὰ τῶν Ἑλλήνων γένη ἐν ἀλλήλοις, καὶ βάρβαρα ἐν Ἕλλησι καὶ Ἑλληνικὰ ἐν βαρβάροις, καθάπερ ὧν Πέρσαι τυραννοῦσι τὰ νῦν διαπεφορημένα καὶ συμπεφορημένα κακῶς ἐσπαρμένα κατοικεῖται.

Tuesday, January 18, 2022

First Sleep in the Odyssey?

Zaria Gorvett, "The forgotten medieval habit of 'two sleeps'," BBC News (January 9, 2022):

And far from being a peculiarity of the Middle Ages, Ekirch began to suspect that the method had been the dominant way of sleeping for millennia — an ancient default that we inherited from our prehistoric ancestors. The first record Ekirch found was from the 8th Century BC, in the 12,109-line Greek epic The Odyssey, while the last hints of its existence dated to the early 20th Century, before it somehow slipped into oblivion.A. Roger Ekirch, At Day's Close: Night in Times Past (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2006), p. 303:

However much it "colonized" the period of wakefulness between intervals of slumber, references to "first sleep" antedate Christianity’s early years of growth. Not only did such figures outside the Church as Pausanias and Plutarch invoke the term in their writings, so, too, did early classical writers, including Livy in his history of Rome, Virgil in the Aeneid, both composed in the first century B.C., and Homer in the Odyssey, written in either the late eighth or early seventh century B.C.Id., p. 406, n. 15, gives a reference to "Allardyce Nicoll, ed., Chapman's Homer: The Iliad, The Odyssey and the Lesser Homerica (Princeton, N.J., 1967), II, 73," i.e.

In his first sleep, call up your hardiest cheer,This is Chapman's rendering of Homer, Odyssey 4.414-416:

Vigour and violence, and hold him there,

In spite of all his strivings to be gone.

τὸν μὲν ἐπὴν δὴ πρῶτα κατευνηθέντα ἴδησθε,Here πρῶτα should be construed with ἴδησθε, not κατευνηθέντα. See Richard John Cunliffe, A Lexicon of the Homeric Dialect (1924; rpt. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1963), p. 350, col. 2, s.v. πρῶτος, sense (5) (e), citing this passage: "With a temporal conjunction, when first, as soon as." A.T. Murray's translation is accurate:

καὶ τότ᾽ ἔπειθ᾽ ὑμῖν μελέτω κάρτος τε βίη τε, 415

αὖθι δ᾽ ἔχειν μεμαῶτα καὶ ἐσσύμενόν περ ἀλύξαι.

Now so soon as you see him laid to rest,The Wikipedia article on Biphasic and polyphasic sleep is typically obtuse:

thereafter let your hearts be filled with strength and courage,

and do you hold him there despite his striving and struggling to escape.

A reference to first sleep in the Odyssey was translated as "first sleep" in the 17th century, but, if Ekirch's hypothesis is correct, was universally mistranslated in the 20th.I suspect that Ekirch's other ancient references are also bogus, but I'm not going to waste time investigating them (please don't contact me if you do).

Labels: typographical and other errors

Meio

Tom Holland, Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World (New York: Basic Books, 2019), p. 99:

In Latin, the same word, meio, meant both ejaculate and urinate.The Oxford Latin Dictionary gives only the meaning urinate, but for the meaning ejaculate see J.N. Adams, The Latin Sexual Vocabulary (London: Duckworth, 1982), p. 142.

Monday, January 17, 2022

Let the People Refrain from Strife and Quarrelling

Cicero, On Divination 1.45.102 (tr. William Armistead Falconer):

Nor is it only to the voices of the gods that the Pythagoreans have paid regard but also to the utterances of men which they term 'omens.' Our ancestors, too, considered such 'omens' worthy of respect, and for that reason, before entering upon any business enterprise, used to say, 'May the issue be prosperous, propitious, lucky, and successful.' At public celebrations of religious rites they gave the command, 'Guard your tongues'; and in issuing the order for the Latin festival the customary injunction was, 'Let the people refrain from strife and quarrelling.'Cf. Livy 38.51.8 (speech of Scipio Africanus; emphasis added; tr. Evan T. Sage):

neque solum deorum voces Pythagorei observitaverunt, sed etiam hominum, quae vocant omina. quae maiores nostri quia valere censebant, idcirco omnibus rebus agendis, 'quod bonum, faustum, felix fortunatumque esset' praefabantur; rebusque divinis, quae publice fierent, ut 'faverent linguis,' imperabatur; inque feriis imperandis, ut 'litibus et iurgiis se abstinerent.'

Therefore, since it is meet on this day to refrain from trials and quarrels, I shall proceed at once from here to the Capitoline to offer homage to Jupiter Optimus Maximus and Juno and Minerva and the other gods who preside over the Capitoline and the citadel, and I shall give thanks to them...

itaque, cum hodie litibus et iurgiis supersederi aequum sit, ego hinc extemplo in Capitolium ad Iovem optimum maximum Iunonemque et Minervam, ceterosque deos qui Capitolio atque arci praesident salutandos ibo, hisque gratias agam...

Sunday, January 16, 2022

A Being from Some Other Sphere

Herman Melville (1819-1891), White-Jacket, chapter 28:

In our man-of-war, this semi-savage, wandering about the gun-deck in his barbaric robe, seemed a being from some other sphere. His tastes were our abominations: ours his. Our creed he rejected: his we. We thought him a loon: he fancied us fools. Had the case been reversed; had we been Polynesians and he an American, our mutual opinion of each other would still have remained the same. A fact proving that neither was wrong, but both right.

Against Almsgiving

Plutarch, Sayings of Spartans: Anonymous 56 (= Moralia 235 D; tr. Frank Cole Babbitt):

A beggar asked alms of a Spartan, who said, "If I should give to you, you will be the more a beggar; and for this unseemly conduct of yours he who first gave to you is responsible, for he thus made you lazy."Related post: Philanthropy.

ἐπαίτης ᾔτησε Λάκωνα. "ἀλλὰ εἰ δοίην σοι," ἔφη, "μᾶλλον πτωχεύσεις, τῆς δὲ ἀσχημοσύνης σου ταύτης ὁ πρῶτος μεταδοὺς αἴτιος, ἀργόν σε ποιήσας."

Friday, January 14, 2022

Rejection of Gods, Fatherland, and Kin

Tacitus, Histories 5.5.2 (tr. Kenneth Wellesley):

Converts to Judaism adopt the same practices, and the very first lesson they learn is to despise the gods, shed all feelings of patriotism and consider parents, children and brothers as readily expendable.Cf. the passages quoted in Battle Cry.

transgressi in morem eorum idem usurpant, nec quicquam prius imbuuntur quam contemnere deos, exuere patriam, parentes liberos fratres vilia habere.

Some Fictional Libraries

John Buchan (1875-1940), Sir Quixote of the Moors, chapter V:

The library I found no bad one — I who in my day have been considered to have something of a taste in books. To be sure there was much wearisome stuff, the work of old divines, and huge commentaries on the Scriptures, written in Latin and plentifully interspersed with Greek and Hebrew. But there was good store of the Classics, both prose and poetry, — Horace, who has ever been my favorite, and Homer, who, to my thinking, is the finest of the ancients. Here, too, I found a Plato, and I swear I read more of him in the manse than I have done since I went through him with M. Clerselier, when we were students together in Paris.Buchan, The Three Hostages, chapter V:

He opened a door and ushered me into an enormous room, which must have occupied the whole space on that floor. It was oblong, with deep bays at each end, and it was lined from floor to ceiling with books. Books, too, were piled on the tables, and sprawled on a big flat couch which was drawn up before the fire. It wasn't an ordinary gentleman's library, provided by the bookseller at so much a yard. It was the working collection of a scholar, and the books had that used look which makes them the finest tapestry for a room. The place was lit with lights on small tables, and on a big desk under a reading lamp were masses of papers and various volumes with paper slips in them. It was workshop as well as library.Buchan, The Island of Sheep, chapter VII:

In the library after dinner I got my notion of Lombard further straightened out, for the room was a museum of the whole run of his interests. Sandy, who could never refrain from looking round any collection of books, bore me out. The walls on three sides were lined to the ceiling with books, which looked in the dim light like rich tapestry hangings. Lombard had kept his old school and college texts, and there was a big section on travel, and an immense amount of biography. He had also the latest works on finance, so he kept himself abreast of his profession. But the chief impression left on me was that it was the library of a man who did not want the memory of any part of his life to slip from him — a good augury for our present job.Id., chapter XII:

That library was the pleasantest room in the house, and it was clearly Haraldsen’s favourite, for it had the air of a place cherished and lived in. Its builder had chosen to give it a fine plaster ceiling, with heraldic panels between mouldings of Norland symbols. It was lined everywhere with books, books which had the look of being used, and which consequently made that soft tapestry which no collection of august bindings can ever provide.

Thursday, January 13, 2022

Remnant of a Mighty Woodland

Wilfrid Scawen Blunt (1840-1922), "Worth Forest," in his Poetical Works, Vol. II (London: Macmillan and Co., Limited, 1914), pp. 14-32 (at 18-19):

I love the Forest; 'tis but this one strip

Along the watershed that still dares keep

Its title to such name. Yet once wide grown

A mighty woodland stretched from Down to Down,

The last stronghold and desperate standing-place

Of that indigenous Britannic race

Which fell before the English. It was called

By Rome "Anderida," in Saxon "Weald."

Time and decay, and man's relentless mood,

Have long made havoc of the lower wood

With axe and plough; and now, of all the plain,

These breadths of higher ground alone remain,

In token of its presence. Who shall tell

How long, in these lost wilds of brake and fell,

Or in the tangled groves of oak below,

Gathering his sacred leaf, the mistletoe,

Some Druid priest, forgotten and in need,

May here have kept his rite and owned his creed

After the rest?

Labels: arboricide

A Mixed Crowd Without a Common Purpose

Thucydides 6.17.2-4 (speech of Alcibiades; tr. Jeremy Mynott):

[2] Do not change your minds about the Sicilian expedition on the grounds that we shall be encountering a great power. Their cities swarm with people but they are a very mixed crowd and they have a constantly changing citizen body. [3] For that reason no one is equipped with arms for his personal protection or has established a proper stake in the land, as they would have if it were their own country; instead each person provides himself with whatever public funds he thinks he can extract by special pleading or intrigue, expecting that he will move on elsewhere if things don't work out. [4] It is unlikely that a rabble of this kind will be of one mind in responding to any proposal or will act with a common purpose.

[2] καὶ τὸν ἐς τὴν Σικελίαν πλοῦν μὴ μεταγιγνώσκετε ὡς ἐπὶ μεγάλην δύναμιν ἐσόμενον. ὄχλοις τε γὰρ ξυμμείκτοις πολυανδροῦσιν αἱ πόλεις καὶ ῥᾳδίας ἔχουσι τῶν πολιτῶν τὰς μεταβολὰς καὶ ἐπιδοχάς. [3] καὶ οὐδεὶς δι' αὐτὸ ὡς περὶ οἰκείας πατρίδος οὔτε τὰ περὶ τὸ σῶμα ὅπλοις ἐξήρτυται οὔτε τὰ ἐν τῇ χώρᾳ νομίμοις κατασκευαῖς· ὅτι δὲ ἕκαστος ἢ ἐκ τοῦ λέγων πείθειν οἴεται ἢ στασιάζων ἀπὸ τοῦ κοινοῦ λαβὼν ἄλλην γῆν, μὴ κατορθώσας, οἰκήσειν, ταῦτα ἑτοιμάζεται. [4] καὶ οὐκ εἰκὸς τὸν τοιοῦτον ὅμιλον οὔτε λόγου μιᾷ γνώμῃ ἀκροᾶσθαι οὔτε ἐς τὰ ἔργα κοινῶς τρέπεσθαι.

A Gathering of Intellectuals

John Buchan (1875-1940), The Island of Sheep, chapter VII:

'It was the usual round-up of rootless intellectuals, and the talk was the kind of thing you expect—terribly knowing and disillusioned and conscientiously indecent. I remember my grandfather had a phrase for the smattering of cocksure knowledge which was common in his day—the "culture of the Mechanics' Institute." I don't know what the modern equivalent would be—perhaps the "culture of the BBC." Our popular sciolism is different—it is a smattering not so much of facts as of points of view. But the youths and maidens at this party hadn't even that degree of certainty. They took nothing for granted except their own surpassing intelligence, and their minds were simply nebulae of atoms.'

Wednesday, January 12, 2022

Big Brother

Xenophon, Cyropaedia 8.2.12 (tr. Walter Miller):

And thus the saying comes about, "The king has many ears and many eyes"; and people are everywhere afraid to say anything to the discredit of the king, just as if he himself were listening; or to do anything to harm him, just as if he were present. Not only, therefore, would no one have ventured to say anything derogatory of Cyrus to any one else, but every one conducted himself at all times just as if those who were within hearing were so many eyes and ears of the king.

οὕτω δὴ πολλὰ μὲν βασιλέως ὦτα, πολλοὶ δ᾽ ὀφθαλμοὶ νομίζονται· καὶ φοβοῦνται πανταχοῦ λέγειν τὰ μὴ σύμφορα βασιλεῖ, ὥσπερ αὐτοῦ ἀκούοντος, καὶ ποιεῖν ἃ μὴ σύμφορα, ὥσπερ αὐτοῦ παρόντος. οὔκουν ὅπως μνησθῆναι ἄν τις ἐτόλμησε πρός τινα περὶ Κύρου φλαῦρόν τι, ἀλλ᾽ ὡς ἐν ὀφθαλμοῖς πᾶσι καὶ ὠσὶ βασιλέως τοῖς ἀεὶ παροῦσιν οὕτως ἕκαστος διέκειτο.

The Romans

Robert A. Kaster, The Appian Way: Ghost Road, Queen of Roads (2012; rpt. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014), p. 117:

Whereas earlier generations of British scholars and intellectuals tended to admire the Roman Empire as a forerunner of their own, the consensus in postimperial Britain has shifted, and there now seems to be broad agreement that the Romans were bastards. My view is that the Romans were what they were, and that understanding what they were does not advance by taking an attitude toward them, especially when the attitude is one of moral superiority.

Tuesday, January 11, 2022

Here's a Text for You

John Buchan (1875-1940), The Island of Sheep, chapter VI:

I found Macgillivray reading Greek with his feet on the mantelpiece and the fire out. He was a bit of a scholar and kept up his classics.Id.:

He picked up the book he had been reading.Herodotus 3.40.2-3 (tr. A.D. Godley):

'Here's a text for you,' he said. 'It is Herodotus. This is the advice he makes Amasis give to his friend Polycrates. I'll translate. "I know that the Gods are jealous, for I cannot remember that I ever heard of any man who, having been constantly successful, did not at last utterly perish." That's worth thinking about. You've been amazingly lucky, but you mustn't press your luck too far. Remember, the Gods are jealous.'

But I like not these great successes of yours; for I know how jealous are the gods; and I do in some sort desire for myself and my friends a mingling of prosperity and mishap, and a life of weal and woe thus chequered, rather than unbroken good fortune. For from all I have heard I know of no man whom continual good fortune did not bring in the end to evil, and utter destruction.Related post: Variations on a Theme.

ἐμοὶ δὲ αἱ σαὶ μεγάλαι εὐτυχίαι οὐκ ἀρέσκουσι, τὸ θεῖον ἐπισταμένῳ ὡς ἔστι φθονερόν· καί κως βούλομαι καὶ αὐτὸς καὶ τῶν ἂν κήδωμαι τὸ μέν τι εὐτυχέειν τῶν πρηγμάτων τὸ δὲ προσπταίειν, καὶ οὕτω διαφέρειν τὸν αἰῶνα ἐναλλὰξ πρήσσων ἢ εὐτυχέειν τὰ πάντα. οὐδένα γάρ κω λόγῳ οἶδα ἀκούσας ὅστις ἐς τέλος οὐ κακῶς ἐτελεύτησε πρόρριζος, εὐτυχέων τὰ πάντα.

Monday, January 10, 2022

I Will Not Be a Slave

Plutarch, Sayings of Spartans: Anonymous 38 (= Moralia 234 B-C; tr. Frank Cole Babbitt, with his note):

A Spartan boy, being taken captive by Antigonus the king and sold, was obedient in all else to the one who had bought him, that is, in everything which he thought fitting for a free person to do, but when his owner bade him bring a chamber-pot, he would not brook such treatment, saying, "I will not be a slave"; and when the other was insistent, he went up upon the roof, and saying, "You will gain much by your bargain," he threw himself down and ended his life.cSeneca, Letters to Lucilius 77.14 (tr. Richard M. Gummere):

c Cf. Moralia, 242 D (30), infra. This story is repeated by Philo Judaeus, Every Virtuous Man is Free, chap. xvii. (882 c); Seneca, Epistulae Moral. no. 77 (x.1.14), and is referred to by Epictetus, i.2.

παῖς Σπαρτιάτης αἰχμαλωτισθεὶς ὑπ᾽ Ἀντιγόνου τοῦ βασιλέως καὶ πραθεὶς τὰ μὲν ἄλλα πάντα ὑπήκοος ἦν τῷ πριαμένῳ, ὅσα ᾤετο προσήκειν ἐλευθέρῳ ποιεῖν· ὡς δὲ προσέταξεν ἀμίδα κομίζειν, οὐκ ἠνέσχετο εἰπών, "οὐ δουλεύσω." ἐνισταμένου δὲ ἐκείνου, ἀναβὰς ἐπὶ τὸν κέραμον καὶ εἰπών, "ὀνήσῃ τῆς ὠνῆς," ἔβαλεν ἑαυτὸν κάτω καὶ ἐτελεύτα.

ὀνήσῃ Wyttenbach: εἴση codd.: οἰμώξῃ Meziriacus: οὐκ ὀνήσῃ Cobet: οἴ σοι Bernardakis: μετανοήσῃ Babbitt

The story of the Spartan lad has been preserved: taken captive while still a stripling, he kept crying in his Doric dialect, "I will not be a slave!" and he made good his word; for the very first time he was ordered to perform a menial and degrading service, and the command was to fetch a chamber-pot, he dashed out his brains against the wall.

Lacon ille memoriae traditur inpubis adhuc, qui captus clamabat "non serviam" sua illa Dorica lingua, et verbis fidem inposuit; ut primum iussus est servili fungi et contumelioso ministerio, adferre enim vas obscenum iubebatur, inlisum parieti caput rupit.

The Old Squire

Wilfrid Scawen Blunt (1840-1922), "The Old Squire," in his Poetical Works, Vol. II (London: Macmillan and Co., Limited, 1914), pp. 11-13 (at p. 12, from stanza VIII):

The new world still is all less fairId., p. 13 (stanza XIV):

Than the old world it mocks.

Nor has the world a better thing,Id. (from stanza XVII):

Though one should search it round,

Than thus to live one's own sole king,

Upon one's own sole ground.

I like to be as my fathers were,

In the days ere I was born.

Insidious Influences

John Scheid, An Introduction to

Roman Religion, tr. Janet Lloyd (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2003), p. 17:

But none of us can escape our prejudices and the assumptions drawn from our own society and history. Even if we were to bury ourselves in antiquity and read only the ancient sources, we would still hardly be able to guard against those insidious influences. A better tactic is to remain conscious of the weight brought to bear by the recent past and the implicit cultural attitudes which threaten to distort our judgement, and then to act accordingly, with those influences in mind.

Sunday, January 09, 2022

Knowledge

Plutarch, Sayings of Spartans: Anonymous 37 (= Moralia 234 B; tr. Frank Cole Babbitt):

A Spartan being asked what he knew, said, "How to be free."

Λάκων ἐρωτηθεὶς τί ἐπίσταται, εἶπεν "ἐλεύθερος εἶναι."

Christian Values

Tom Holland, Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World (New York: Basic Books, 2019), pp. 16-17:

The more years I spent immersed in the study of classical antiquity, so the more alien I increasingly found it. The values of Leonidas, whose people had practised a peculiarly murderous form of eugenics and trained their young to kill uppity Untermenschen by night, were nothing that I recognised as my own; nor were those of Caesar, who was reported to have killed a million Gauls, and enslaved a million more. It was not just the extremes of callousness that unsettled me, but the complete lack of any sense that the poor or the weak might have the slightest intrinsic value. Why did I find this disturbing? Because, in my morals and ethics, I was not a Spartan or a Roman at all. That my belief in God had faded over the course of my teenage years did not mean that I had ceased to be Christian. For a millennium and more, the civilisation into which I had been born was Christendom. Assumptions that I had grown up with — about how a society should properly be organised, and the principles that it should uphold — were not bred of classical antiquity, still less of 'human nature', but very distinctively of that civilisation's Christian past.

Words and Their Sounds

Augustine, On Dialectic 6 (tr. Jan Pinborg):

For example, 'lene' (smoothly) itself has a smooth sound. Likewise, who does not by the name itself judge 'asperitas' (roughness) to be rough? It is gentle to the ears when we say 'voluptas' (pleasure); it is harsh when we say 'crux' (cross). Thus the words are perceived in the way the things themselves affect us. Just as honey itself affects the taste pleasantly, so its name 'mel' affects the hearing smoothly. 'Acre' (bitter) is harsh in both ways. Just as the words 'lana' (wool) and 'vepres' (brambles) are heard, so the things themselves are felt. The Stoics believed that these cases where the impression made on the senses by the things is in harmony with the impression made on the senses by the sounds are, as it were, the cradle of words. From this point they believed that the license for naming had proceeded to the similarity of things themselves to each other.

ut ipsum 'lene' cum dicimus leniter sonat. quis item 'asperitatem' non et ipso nomine asperam iudicet? lene est auribus cum dicimus 'voluptas', asperum cum dicimus 'crux'. ita res ipsae adficiunt, ut verba sentiuntur. 'mel', quam suaviter gustum res ipsa, tam leniter nomine tangit auditum. 'acre' in utroque asperum est. 'lana' et 'vepres', ut audiuntur verba, sic illa tanguntur. haec quasi cunabula verborum esse crediderunt, ubi sensus rerum cum sonorum sensu concordarent. hinc ad ipsarum inter se rerum similitudinem processisse licentiam nominandi.

Always To Be Right

William Makepeace Thackeray (1811-1863), Vanity Fair, chapter 35:

He firmly believed that everything he did was right, that he ought on all occasions to have his own way—and like the sting of a wasp or serpent his hatred rushed out armed and poisonous against anything like opposition. He was proud of his hatred as of everything else. Always to be right, always to trample forward, and never to doubt, are not these the great qualities with which dullness takes the lead in the world?

Saturday, January 08, 2022

Moral Imbeciles

John Buchan (1875-1940), The Three Hostages, chapter II:

"Poor devils," Macgillivray repeated. "It is for their Maker to judge them, but we who are trying to patch up civilisation have to see that they are cleared out of the world. Don't imagine that they are devotees of any movement, good or bad. They are what I have called them, moral imbeciles, who can be swept into any movement by those who understand them. They are the neophytes and hierophants of crime, and it is as criminals that I have to do with them. Well, all this desperate degenerate stuff is being used by a few clever men who are not degenerates or anything of the sort, but only evil. There has never been such a chance for a rogue since the world began."

Familiar Places

Cicero, On Friendship 19.68 (tr. William Armistead Falconer):

See J.C. Davies, "Was Cicero Aware of Natural Beauty?" Greece & Rome 18.2 (October, 1971) 152-165 (also rendered as "wild, rugged" on p. 154).

And habit is strong in the case not only of animate, but also of inanimate things, since we delight even in places, though rugged and wild, in which we have lived for a fairly long time.rugged and wild: literally, mountainous and wooded.

nec vero in hoc, quod est animal, sed in eis etiam, quae sunt inanima, consuetudo valet, cum locis ipsis delectemur, montuosis etiam et silvestribus, in quibus diutius commorati sumus.

See J.C. Davies, "Was Cicero Aware of Natural Beauty?" Greece & Rome 18.2 (October, 1971) 152-165 (also rendered as "wild, rugged" on p. 154).

Thursday, January 06, 2022

What Can Be Said About an Individual

Christopher Craig, "Audience Expectations, Invective, and Proof," in Jonathan Powell and Jeremy Patterson, edd., Cicero the Advocate (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), pp. 187-213 (at 188):

The young Cicero, at Inv. 1.34–6, gives for arguments from character (ex persona) a set of topics that are so comprehensive that they embrace almost anything that one could say about a given individual.4I'm sure that someone must have investigated these topics as components of ancient biography. I don't see any references to this passage in Friedrich Leo, Die griechisch-römische Biographie nach ihrer litterarischen Form (Leipzig: B.G. Teubner, 1901), but Craig S. Keener, Christobiography: Memory, History, and the Reliability of the Gospels (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2019), somewhere (I have only a digital copy without page numbers) cites Cicero, On the Composition of Arguments 1.25.36, i.e. this passage.

4 (1) nomen (name); (2) natura (nature, including, but not limited to: gender, ethnic group, country, kinship, age; physical appearance, strength and quickness, intelligence, memory; affability, modesty, patience and their opposites); (3) victus (manner of life, including upbringing, teachers, friends, occupation, financial management and home life); (4) fortuna (fortune, including status as slave or free, rich or poor, private citizen or officeholder, and if the latter, whether he acquired the position justly, is successful, is famous, or the opposites; what sort of children he has. If the target is dead, what was the manner of death? (5) habitus (habit); (6) affectio (emotional reactions), (7) studium (interest or devotion to a pursuit such as philosophy, poetry, geometry, or literature); (8) consilium (deliberate plan to do or not do something); (9–11) facta, casus, orationes (what he did, what happened to him, what he said, treated by Cicero as a group).

An Unrepentant Sensualist

Alan Watts (1915-1973), In My Own Way: An Autobiography, 1915-1965 (New York: Pantheon Books, 1972), pp. 47-48:

I am an unrepentant sensualist. I am an immoderate lover of women and the delights of sexuality, of the greatest French, Chinese, and Japanese cuisine, of wines and spirituous drinks, of smoking cigars and pipes, of gardens, forests, and oceans, of jewels and paintings, of colorful clothes, and of finely bound and printed books. If I were extremely rich I would collect incunabula and rare editions, Japanese swords, Tibetan jewelry, Persian miniatures, Celtic illuminated manuscripts, Chinese paintings and calligraphies, embroideries and textiles from India, images of Buddhas, Oriental carpets, Navajo necklaces, Limoges enamels, and venerable wines from France.

Respect for Elders

Plutarch, Life of Lycurgus 20.6 (tr. Bernadotte Perrin):

Another, seeing men seated on stools in a privy, said: "May I never sit where I cannot give place to an elder."Plutarch, Sayings of Spartans: Anonymous 12 (= Moralia 232 F; tr. Frank Cole Babbitt):

ἕτερος δέ τις ἰδὼν ἐν ἀποχωρήσει θακεύοντας ἐπὶ δίφρων ἀνθρώπους, "μὴ γένοιτο," εἶπεν, "ἐνταῦθα καθίσαι ὅθεν οὐκ ἔστιν ὑπεξαναστῆναι πρεσβυτέρῳ."

Someone, seeing men seated on stools in a privy, said, "God forbid that I should ever sit where it is not possible to rise and yield my place to an older man."Related posts:

ἰδών τις ἐν ἀποχωρήσει θακέοντας ἐπὶ δίφρων ἀνθρώπους, "μὴ γένοιτο," εἶπεν "ἐνταῦθα καθίσαι ὅθεν οὐκ ἔστιν ἐξαναστῆναι πρεσβυτέρῳ."

Wednesday, January 05, 2022

Stay at Home

Robert Herrick, "To His Muse," lines 19-20:

Stay then at home, and do not goId., lines 25-26:

Or fly abroad to seek for woe.

That man's unwise will search for ill,

And may prevent it sitting still.

The Eye of Zeus

Hesiod, Works and Days 265-269 (tr. Glenn W. Most):

A man contrives evil for himself when he contrives evil for someone else, and an evil plan is most evil for the planner. Zeus' eye, which sees all things and knows all things, perceives this too, if he so wishes, and he is well aware just what kind of justice this is which the city has within it.M.L. West on line 267:

οἷ γ᾽ αὐτῷ κακὰ τεύχει ἀνὴρ ἄλλῳ κακὰ τεύχων,

ἡ δὲ κακὴ βουλὴ τῷ βουλεύσαντι κακίστη.

πάντα ἰδὼν Διὸς ὀφθαλμὸς καὶ πάντα νοήσας

καί νυ τάδ᾽, αἴ κ᾽ ἐθέλῃσ᾽, ἐπιδέρκεται, οὐδέ ἑ λήθει,

οἵην δὴ καὶ τήνδε δίκην πόλις ἐντὸς ἐέργει.

A Charming Fellow

Heinrich Heine, Buch der Lieder: Die Heimkehr, XXXV (tr. Hal Draper):

I called the devil and he came;German text from Heinrich Heine, Sämtliche Gedichte. Kommentierte Ausgabe (Stuttgart: Philip Reclam jun., 2006), p. 135 (line numbers added):

I looked him over wonderingly.

He isn't ugly and isn't lame,

He's a likable, charming man, I see,

A man in the prime of life, I surmise, 5

Obliging and courteous and worldly-wise.

His diplomatic skill is great,

And he talks very nicely on Church and State.

He's somewhat pale—no wonder, I vow,

For he's studying Sanskrit and Hegel now. 10

His favorite poet is still Fouqué.

He'll put reviewing on the shelf

And do that job no more himself—

Let grandmother Hecate do it today.

For my legal studies he had some praise— 15

He'd dabbled in law in former days.

He said my friendship made him proud,

Nothing was dearer, and so on—and bowed.

He asked if we hadn't met some place—

At the Spanish embassy over the wine? 20

And as I looked him full in the face,

I found him an old acquaintance of mine.

Ich rief den Teufel und er kam,Commentary, id., p. 900:

Und ich sah ihn mit Verwundrung an.

Er ist nicht häßlich und ist nicht lahm,

Er ist ein lieber, charmanter Mann,

Ein Mann in seinen besten Jahren, 5

Verbindlich und höflich und welterfahren.

Er ist ein gescheuter Diplomat,

Und spricht recht schön über Kirch und Staat.

Blaß ist er etwas, doch ist es kein Wunder,

Sanskrit und Hegel studiert er jetzunder. 10

Sein Lieblingspoet ist noch immer Fouqué.

Doch will er nicht mehr mit Kritik sich befassen,

Die hat er jetzt gänzlich überlassen

Der teuren Großmutter Hekate.

Er lobte mein juristisches Streben, 15

Hat früher sich auch damit abgegeben.

Er sagte, meine Freundschaft sei

Ihm nicht zu teuer, und nickte dabei,

Und frug: ob wir uns früher nicht

Schon einmal gesehn beim spanschen Gesandten? 20

Und als ich recht besah sein Gesicht,

Fand ich in ihm einen alten Bekannten.

10 Sanskrit: Sprache der altindischen Dichtung. Heine hörte bei Franz Bopp in Berlin 1821/22 eine Vorlesung »Sanskrit-Sprache und Literatur«.

Hegel: Heine lernte den berühmten Philosophen (1770-1831) bei dem er in Berlin studierte, auch persönlich kennen.

11 Fouqué: Heines Beziehung zu dem spätromantischen Dichter Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué (1777-1843) war gespalten (vgl. auch Junge Leiden: Romanzen IX).

14 Hekate: antike Göttin des Spuks und des Zaubers. Hier ist eine Zeitschrift gleichen Titels gemeint, die 1823 von dem Dramatiker und Kritiker Adolf Müllner herausgegeben wurde. In der Hekate war eine kritische Rezension der Tragödien, nebst einem lyrischen Intermezzo erschienen. Als Müllner später einen Verriß der Reisebilder schrieb, meinte Heine in bezug auf dieses Gedicht: »Dieser Mann kann doch nur verletzen und hat gewiß geglaubt, mein Teufel bezöge sich auf ihn« (auf Merckel, 16.11.1826).

Tuesday, January 04, 2022

Keep Talking

Plutarch, Sayings of Spartans: Lysander 13 (= Moralia 229 E; tr. Frank Cole Babbitt):

When someone was reviling him, he said, "Talk right on, you miserable foreigner, talk, and don't leave out anything if thus you may be able to empty your soul of the vicious notions with which you seem to be filled."

λοιδορουμένου δέ τινος αὐτῷ, εἶπε, "λέγε πυκνῶς, ὦ ξενύλλιον, λέγε μηδὲν ἐλλείπων, ἄν σου δύνῃ τὰν ψυχὰν κενῶσαι κακῶν, ὧν ἔοικας πλήρης εἶναι."

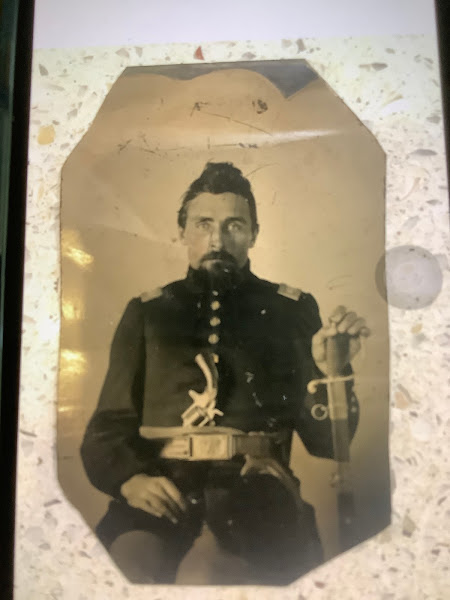

Family Photograph

My great-great-grandfather, Robert E. Gilleland, 2nd Lieutenant, 99th Regiment, Illinois Infantry, company I (taken in 1862 or 1863):

It's of no interest to anyone outside my family, but this blog is a convenient place for me to store the photograph.

Humanitarians

John Buchan (1875-1940), Mr. Standfast, chapter XV (Launcelot Wake speaking):

"I hate more than I love. All we humanitarians and pacifists have hatred as our mainspring. Odd, isn't it, for people who preach brotherly love? But it's the truth. We're full of hate towards everything that doesn't square in with our ideas, everything that jars on our lady-like nerves. Fellows like you are so in love with their cause that they've no time or inclination to detest what thwarts them. We've no cause—only negatives, and that means hatred, and self-torture, and a beastly jaundice of soul."

Monday, January 03, 2022

Cicero

Robert A. Kaster, The Appian Way: Ghost Road, Queen of Roads (2012; rpt. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014), pp. 101-103:

Marcus Tullius Cicero is unavoidable in my line of work, and not the sort of man who provokes mild emotions in those who make his acquaintance. Loathing and affection are the only choices. By now I have spent enough time in his company, through teaching and writing, to work past the first of those feelings and arrive at the second. Certainly, he is everything that those who loathe him say: an egotist who was impossibly high-maintenance as a friend; often blinkered and bloviating as a statesman; moody, inconstant, and self-dramatizing as a man; and—what finally did him in—not nearly as clever a political player as he thought he was, or as his enemies actually were. Yet he was also a loyal friend in his turn, and witty company, a man who (I think) really did try to do what he thought was right, and who along the way wrote some of the best prose ever composed in any language, with the same impact on the future of Latin that Shakespeare and the King James Version of the Bible have had on English. But above all he left himself exposed and accessible, and that is the thing in the end that moves me beyond simple respect.

A chief reason Cicero is so easy to loathe is that he left so much of himself on view. We know him better than we can know any human being in Western history before Saint Augustine, because no one in the West before Augustine left so large a written legacy of such a personal kind. The texts, and the body of commentary that has grown up around them, fill ten feet of shelving in my office, and my collection is not especially large: speeches, rhetorical treatises, philosophical tracts, and above all the correspondence, over twenty years' worth, that he carried on with family, friends, and enemies. Of course most of the writing is carefully calculated, intended to present the writer in the best possible light in whatever circumstance prompted the writing: that is one of the jobs that rhetoric is supposed to do, and Cicero was a master of the craft. But even though the writing may not offer a transparent window on his soul, it does give excellent access to his lively mind. You see the wheels turning, you come to understand the move that's being made and anticipate the move that's coming next, and in so doing you reach across more than twenty centuries in a way that is exhilarating and moving.

A Lover of Sparta

Plutarch, Life of Lycurgus 20.3 (tr. Bernadotte Perrin):

And Theopompus, when a stranger kept saying, as he showed him kindness, that in his own city he was called a lover of Sparta, remarked: "My good Sir, it were better for thee to be called a lover of thine own city."Plutarch, Sayings of Spartans: Theopompus 2 (= Moralia 221 E; tr. Frank Cole Babbitt):

Θεόπομπος δὲ ξένου τινὸς εὔνοιαν ἐνδεικνυμένου, καὶ φάσκοντος ὡς παρὰ τοῖς αὑτοῦ πολίταις φιλολάκων καλεῖται, "κάλλιον ἦν τοι," εἶπεν, "ὦ ξένε, φιλοπολίταν καλεῖσθαι."

In answer to a man from abroad who said that among his own citizens he was called a lover of Sparta, he said, "It would be better to be called a lover of your own country than a lover of Sparta."

πρὸς δὲ τὸν ξένον τὸν λέγοντα ὅτι παρὰ τοῖς αὑτοῦ πολίταις καλεῖται φιλολάκων, "κρεῖσσον" ἔφη "ἦν σε φιλοπολίτην ἢ φιλολάκωνα καλεῖσθαι."

Guest Worker Program

Homer, Odyssey 17.382-387 (tr. Peter Green):

For who'd himself seek out and invite any stranger

from abroad, except maybe some kind of public worker—

a prophet, a healer of sickness, a carpenter—even a godlike

minstrel, who gives delight with his singing? Such men

are invited worldwide on mankind's boundless earth,

but no man would bring in a beggar to devour his substance!

τίς γὰρ δὴ ξεῖνον καλεῖ ἄλλοθεν αὐτὸς ἐπελθὼν

ἄλλον γ᾽, εἰ μὴ τῶν οἳ δημιοεργοὶ ἔασι,

μάντιν ἢ ἰητῆρα κακῶν ἢ τέκτονα δούρων,

ἢ καὶ θέσπιν ἀοιδόν, ὅ κεν τέρπῃσιν ἀείδων; 385

οὗτοι γὰρ κλητοί γε βροτῶν ἐπ᾽ ἀπείρονα γαῖαν·

πτωχὸν δ᾽ οὐκ ἄν τις καλέοι τρύξοντα ἓ αὐτόν.

Saturday, January 01, 2022

A Common Language

Gustave Flaubert, Sentimental Education, part III, chapter I (tr. Robert Baldick):

Michel-Évariste-Népomucène Vincent, sometime professor, expresses the hope that European democracy will adopt a common language. A dead language might be used, such as Latin of the best period.Or, to bring the passage up to date:

'No! No Latin!' cried the architect.

'Why not?' retorted a schoolmaster.

And the two men launched into an argument in which others joined, each person trying to show off with some witty remarks. Soon the discussion became so tedious that a good many people walked out.

Michel-Evariste-Népomucène Vincent, ex-professeur, émet le voeu que la démocratie européenne adopte l'unité de langage. On pourrait se servir d’une langue morte, comme par exemple du latin perfectionné.

— « Non! pas de latin! » s'écria l'architecte.

— « Pourquoi? » reprit un maître d'études.

Et ces deux messieurs engagèrent une discussion, où d’autres se mêlèrent, chacun jetant son mot pour éblouir, et qui ne tarda pas à devenir tellement fastidieuse, que beaucoup s'en allaient.

'No! No Latin!' cried Pope Francis.

The Way We Live Now

John Buchan (1875-1940), Mr. Standfast, chapter I:

Newer› ‹Older

You will hear everything you regard as sacred laughed at and condemned, and every kind of nauseous folly acclaimed, and you must hold your tongue and pretend to agree.