Friday, July 31, 2020

Goodbye to Google

The Gates Are Open

Nahum 3:13 (NIV):

Look at your troops — they are all weaklings. The gates of your land are wide open to your enemies; fire has consumed the bars of your gates.

The Detritus of Alien Ideas

Georg Christoph Lichtenberg (1742-1799), Waste Books B.264 (tr. Steven Tester):

In our premature and often all too extensive reading, by which we acquire numerous materials without constructing anything from them and which accustoms our memory to keep house for sensibility and taste, a profound philosophy is often required to restore to our feelings their initial state of innocence: to extricate one's self from the detritus of alien ideas, to begin to feel for oneself, to speak for oneself, and, I might almost say, to exist for oneself.

Bei unsrem frühzeitigen und oft gar zu häufigen Lesen, wodurch wir so viele Materialien erhalten ohne sie zu verbauen, wodurch unser Gedächtnis gewöhnt wird die Haushaltung für Empfindung und Geschmack zu führen, da bedarf es oft einer tiefen Philosophie unserm Gefühl den ersten Stand der Unschuld wiederzugeben, sich aus dem Schutt fremder Dinge herauszufinden, selbst anfangen zu fühlen, und selbst zu sprechen und ich mögte fast sagen auch einmal selbst zu existieren.

The Example of Our Ancestors

Edmund Burke (1729-1797), Reflections on the Revolution in France, in his Works, Vol. IV (London: Francis & John Rivington, 1852), pp. 354-355:

Our people will find employment enough for a truly patriotic, free, and independent spirit, in guarding what they possess from violation. I would not exclude alteration neither; but even when I changed, it should be to preserve. I should be led to my remedy by a great grievance. In what I did, I should follow the example of our ancestors. I would make the reparation as nearly as possible in the style of the building. A politic caution, a guarded circumspection, a moral rather than a complexional timidity, were among the ruling principles of our forefathers in their most decided conduct. Not being illuminated with the light of which the gentlemen of France tell us they have got so abundant a share, they acted under a strong impression of the ignorance and fallibility of mankind. He that had made them thus fallible, rewarded them for having in their conduct attended to their nature. Let us imitate their caution, if we wish to deserve their fortune, or to retain their bequests.

Battle Cry

Douglas Brinkley, "Introduction" to Edward Abbey, The Monkey Wrench Gang (New York: Perennial Classics, 2000), pp. xv-xxiv (at xx):

Their battle cry is "Keep it like it was.""Keep it like it was" occurs in Chapters 2 (p. 20) and 6 (p. 82).

Thursday, July 30, 2020

Disaster and Disgrace

[Euripides,] Rhesus 756-761 (tr. David Kovacs):

Disaster has struck, and over and above disaster disgrace: that makes disaster twice as bad. To die gloriously, if die one must, though it is of course painful for him who dies, is a source of magnificence for the survivors and a glory to their houses. But we perished foolishly and ingloriously.The same, tr. Richmond Lattimore:

κακῶς πέπρακται κἀπὶ τοῖς κακοῖσι πρὸς

αἴσχιστα· καίτοι δὶς τόσον κακὸν τόδε·

θανεῖν γὰρ εὐκλεῶς μέν, εἰ θανεῖν χρεών,

λυπρὸν μὲν οἶμαι τῷ θανόντι—πῶς γὰρ οὔ;—

τοῖς ζῶσι δ᾿ ὄγκος καὶ δόμων εὐδοξία. 760

ἡμεῖς δ᾿ ἀβούλως κἀκλεῶς ὀλώλαμεν.

There has been wickedness done here. More than wickedness:

shame too, which makes the evil double its own bulk.

To die with glory, if one has to die at all,

is still, I think, pain for the dier, surely so,

yet grandeur left for his survivors, honor for his house.

But death to us came senseless and inglorious.

Humor

Berthold L. Ullman, "The Ph.D. Degree in the Classics," Classical Journal 41.8 (May, 1946) 363-366 (at 366):

I know of no easier way to elicit a laugh than to cite the names of a few doctoral dissertations.

Church Fathers

Friedrich Nietzsche, The Anti-Christ § 59 (tr. Judith Norman):

Just read any Christian agitator, Saint Augustine, for example, and you will realize, you will smell the sort of unclean people this brought to the top. You would be lying to yourself if you thought that the leaders of the Christian movement were lacking in intelligence: — oh, they are shrewd, shrewd to the point of holiness, these dear Mr Church Fathers! What they lack is something entirely different. Nature neglected them, — it forgot to give them a modest dowry of respectable, decent, cleanly instincts ... Just between us, they are not even men.

Man lese nur irgend einen christlichen Agitator, den heiligen Augustin zum Beispiel, um zu begreifen, um zu riechen, was für unsaubere Gesellen damit obenauf gekommen sind. Man würde sich ganz und gar betrügen, wenn man irgendwelchen Mangel an Verstand bei den Führern der christlichen Bewegung voraussetzte: — oh sie sind klug, klug bis zur Heiligkeit, diese Herrn Kirchenväter! Was ihnen abgeht, ist etwas ganz Anderes. Die Natur hat sie vernachlässigt, — sie vergass, ihnen eine bescheidne Mitgift von achtbaren, von anständigen, von reinlichen Instinkten mitzugeben ... Unter uns, es sind nicht einmal Männer.

Recommendation

Georg Christoph Lichtenberg (1742-1799), Waste Books A.137 (tr. Steven Tester):

Growing wiser means becoming increasingly acquainted with the errors to which our instrument of feeling and judging may be subject. Today, cautiousness in judgment is to be recommended to each and every one.

Weiser werden heißt immer mehr und mehr die Fehler kennen lernen, denen dieses Instrument, womit wir empfinden und urteilen, unterworfen sein kann. Vorsichtigkeit im Urteilen ist was heutzutage allen und jeden zu empfehlen ist.

A Translation From the French

Fyodor Dostoyevsky, The Devils, tr. David Magarshack (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1971), p. 66:

'Isn't that a translation from the French?' he laughed, tapping the book with his fingers.

'No, that's not a translation from the French!' Liputin cried spitefully, jumping up from his chair. 'That's a translation from the universal language of mankind, and not only from the French! From the language of the universal social republic and universal harmony — that's what it is, sir! And not only from the French!'

'Dear me,' Nicholas went on, laughing; 'but there isn't such a language, is there?'

Wednesday, July 29, 2020

Appearances

Euripides, Bacchae 480 (my translation):

To an uneducated man someone speaking wisely will seem to be thinking foolishly.

δόξει τις ἀμαθεῖ σοφὰ λέγων οὐκ εὖ φρονεῖν.

The Cream of the Crop

James Hankins, "Cultural Revolution in the Renaissance?" Quillette (July 29, 2020):

I remember some years ago, well-launched into the introductory lecture of my course on Renaissance Florence, being stopped by a student in the first row, vigorously waving her hand. "Please, professor, I'm trying to remember: which comes first, the Renaissance or the Enlightenment?" This from a Harvard undergraduate, supposedly the cream of America's high school crop.

A Scholar

Fyodor Dostoyevsky, The Devils, tr. David Magarshack (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1971), p. 23:

And yet he was undoubtedly a highly intelligent and talented man, a man who was, as it were, even a scholar, though so far as his scholarship was concerned ... well, he did not really make any important contribution to scholarship, indeed none at all, I believe.

Tuesday, July 28, 2020

Prejudices

Georg Christoph Lichtenberg (1742-1799), Waste Books A.58 (tr. Steven Tester):

Prejudices are, so to speak, the acquired instincts of human beings: through prejudice we can accomplish many things we would find too difficult to think through to the point of decision.

Die Vorurteile sind so zu reden die Kunsttriebe der Menschen, sie tun dadurch vieles, das ihnen zu schwer werden würde bis zum Entschluß durchzudenken, ohne alle Mühe.

Cleverness Is Not Wisdom

Euripides, Bacchae 386-401 (tr. E.P. Coleridge):

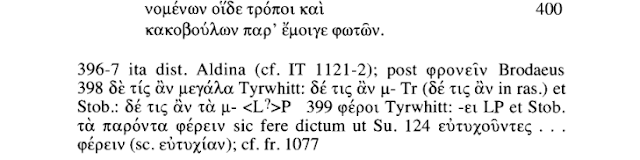

John Edwin Sandys ad loc.:

David Kovacs, Euripidea Tertia (Leiden: Brill, 2003), pp. 124-126 (D. = James Diggle):

The end of all unbridled speech and lawless senselessness is misery; but the life of calm repose and the rule of reason abide unshaken and support the home; for far away in heaven though they dwell, the powers divine behold man's state. Sophistry is not wisdom, and to indulge in thoughts beyond man's ken is to shorten life; and if a man on such poor terms should aim too high, he may miss the pleasures in his reach. These, to my mind, are the ways of madmen and idiots.E.R. Dodds ad loc.:

ἀχαλίνων στομάτων

ἀνόμου τ᾽ ἀφροσύνας

τὸ τέλος δυστυχία·

ὁ δὲ τᾶς ἡσυχίας

βίοτος καὶ τὸ φρονεῖν 390

ἀσάλευτόν τε μένει καὶ

συνέχει δώματα· πόρσω

γὰρ ὅμως αἰθέρα ναίον-

τες ὁρῶσιν τὰ βροτῶν οὐρανίδαι.

τὸ σοφὸν δ᾽ οὐ σοφία 395

τό τε μὴ θνητὰ φρονεῖν

βραχὺς αἰών· ἐπὶ τούτῳ

δέ τις ἂν μεγάλα διώκων

τὰ παρόντ᾽ οὐχὶ φέροι. μαι-

νομένων οἵδε τρόποι καὶ 400

κακοβούλων παρ᾽ ἔμοιγε φωτῶν.

John Edwin Sandys ad loc.:

David Kovacs, Euripidea Tertia (Leiden: Brill, 2003), pp. 124-126 (D. = James Diggle):

Monday, July 27, 2020

Copious Stream of Pontifical Mugwumpery

Winston Churchill, speech to the House of Commons (February 22, 1933):

These well-meaning gentlemen of the British Broadcasting Corporation have absolutely no qualifications and no claim to represent British public opinion. They have no right to say that they voice the opinions of English or British people whatever. If anyone can do that it is His Majesty's Government; and there may be two opinions about that. It would be far better to have sharply contrasted views in succession, in alternation, than to have this copious stream of pontifical, anonymous mugwumpery with which we have been dosed so long.

Little Nations

Wislawa Szymborska, "Voices," Poems New and Collected 1957–1977, tr. Stanislaw Barańczak and Clare Cavanagh (Orlando: Harcourt, Inc., 2000), pp. 116-117:

You can’t move an inch, my dear Marcus Emilius,

without Aborigines sprouting up as if from the earth itself.

Your heel sticks fast amidst Rutulians.

You founder knee-deep in Sabines and Latins.

You’re up to your waist, your neck, your nostrils

in Aequians and Volscians, dear Lucius Fabius.

These irksome little nations, thick as flies.

It’s enough to make you sick, dear Quintus Decius.

One town, then the next, then the hundred and seventieth.

The Fidenates’ stubbornness. The Feliscans’ ill will.

The shortsighted Ecetrans. The capricious Antemnates.

The Labicanians and Pelignians, offensively aloof.

They drive us mild-mannered sorts to sterner measures

with every new mountain we cross, dear Gaius Cloelius.

If only they weren’t always in the way, the Auruncians, the Marsians,

but they always do get in the way, dear Spurius Manlius.

Tarquinians where you’d least expect them, Etruscans on all sides.

If that weren’t enough, Volsinians and Veientians.

The Aulertians, beyond all reason. And, of course,

the endlessly vexatious Sapinians, my dear Sextus Oppius.

Little nations do have little minds.

The circle of thick skulls expands around us.

Reprehensible customs. Backward laws.

Ineffectual gods, my dear Titus Vilius.

Heaps of Hernicians. Swarms of Murricinians.

Antlike multitudes of Vestians and Samnites.

The farther you go, the more there are, dear Servius Follius.

These little nations are pitiful indeed.

Their foolish ways require supervision

with every new river we ford, dear Aulus Iunius.

Every new horizon threatens me.

That’s how I’d put it, my dear Hostius Melius.

To which I, Hostus Melius, would reply, my dear

Appius Papius: March on! The world has got to end somewhere.

Sunday, July 26, 2020

Wolf Names

Michael P. Speidel, Ancient Germanic Warriors: Warrior Styles from Trajan's Column to Icelandic Sagas (London: Routledge, 2004), p. 16, with note on p. 190:

Firsthand evidence of wolf sympathy among Germanic tribes of Trajan's time also comes from names. The earliest known Germanic wolf name, one Ulfenus, appears on a Trajanic inscription from Rimburg near Aachen, followed by one Ulfus, also from Roman Germany. Some have wondered about the widespread use in Lower Germany of the Latin name Ulpius, which to German ears sounded like "wolf." Ulpius is, of course, Trajan's name, and for that reason alone would have been widely used in Lower Germany. But Ulpius also meant "wolf" in older Latin, and the punning name Ulpius Lupio suggests that the original meaning of Trajan’s name was still understood. Beyond the Empire's borders, a second-century runic inscription from Himlingøje in Denmark names a Widuhu[n]daR (Woodhound—Wolf). Indo-European twin-root names such as this were aristocratic wish-names: parents hoped their sons would be "wolves." As with dragons, people feared wolves, yet stood in awe of them and wanted to be like them.30My own last name contains a wolfish element.

30 Animal standards ("ferarum imagines"): Tacitus, Histories 4.22.2. Wulfenus: Nesselhauf, "Inschriften" 1937, nos. 245ff.; 251. Birkhan, "Germanen" 1970, 379. (W)ulfus: CIL III, 1839. See also the joint wolf- and bear-names discussed on p. 41. Ulpius: CIL XIII, 11810; Dessau, Inscriptiones 1892–1916, 7080 additions; Syme, Tacitus II 1958, 786; Wiegels, "Ulpius" 1999- Honored: Syme, Tacitus II 1958, 786. Meant wolf: Pokorny, Wörterbuch 1959, 1178f.; Cagnat, Inscriptiones 1911, vol. 3, no. 20 (Cios, Bithynia); an Ulpius Lupus, perhaps a Batavian, is found in Speidel, Denkmäler 1994, 35; also AE 1990, 516. A new Batavian Lupus of Trajan's time: Birley, Garrison 2002, 100. Woodhound: Müller, Personennamen 1970, 69; 212; Birkhan, "Germanen" 1970, 378f.; Düwel, Runenkunde 2001, 2; cf. Förstemann, Namenbuch 1900, 1509: Walthun. Indo-European names: Schmitt, "Altertumskunde" 2000, 400. Wolf: Müller, Personennamen 1970, 201 and 210f. Feared, etc.: Unruh, "Wargus" 1954, 9; Müller, Personennamen 1970, 191ff. Dragons: Müller, Personennamen 1970, 188ff. Be like them: e.g. Ingiald in Snorri Sturluson, Heimskringla, Ynglinga saga 34.

The Bitterness of Controversy

Samuel Johnson, Rasselas, chapter 28:

'Let us not add,' said the prince, 'to the other evils of life, the bitterness of controversy, nor endeavour to vie with each other in subtleties of argument.'

Buying and Selling

Primo Levi (1919-1987), The Periodic Table, tr. Raymond Rosenthal (New York: Schocken Books, 1984), p. 169:

Anyone who has the trade of buying and selling is easily recognized: he has a vigilant eye and a tense face, he fears fraud or considers it, and he is on guard like a cat at dusk. It is a trade that tends to destroy the immortal soul; there have been courtier philosophers, lens-grinding philosophers, and even engineer and strategist philosophers; but no philosopher, so far as I know, was a wholesaler or storekeeper.

Chi per mestiere compra o vende si riconosce facilmente: ha l'occhio vigile e il volto teso, teme la frode o la medita, e sta in guardia come un gatto all'imbrunire. È un mestiere che tende a distruggere l'anima immortale; ci sono stati filosofi cortigiani, filosofi pulitori di lenti, perfino filosofi ingegneri e strateghi, ma nessun filosofo, che io sappia, era grossista o bottegaio.

Three Ships

Anonymous, "The Capture of Constantinople", tr. Victoria Clark, Why Angels Fall: A Journey Through Orthodox Europe from Byzantium to Kosovo (London: Picador, 2011), page number unknown:

See also:

'But send a message to the West asking for three ships to come;The Greek, from George Thomson, The Greek Language (Cambridge: W. Heffer and Sons, 1960), p. 53:

one to take the Cross away, another the Holy Bible,

the third, the best of them, our Holy Altar,

lest the dogs seize it from us and defile it.'

The Virgin was distressed, and the holy icons wept.

'Hush, Lady — do not weep so profusely,

after years and centuries, they will be yours again.'

Μόν᾿ στεῖλτε λόγο στὴ Φραγκιά, νά ῾ρθοῦνε τρία καράβια,

Τό ῾να νὰ πάρει τὸ Σταυρό, καὶ τἄλλο τὸ βαγγέλιο,

Τὸ τρίτο, τὸ καλύτερο, τὴν ἅγια τράπεζά μας,

Μὴ μᾶς τὴν πάρουν τὰ σκυλιὰ καὶ μᾶς τὴ μαγαρίσουν.

Ἡ Δέσποινα ταράχτηκε, καὶ δάκρυσαν οἱ εἰκόνες.

Σώπασε, κυρὰ Δέσποινα, καὶ μὴ πολυδακρύζεις·

Πάλι μὲ χρόνους, μὲ καιρούς, πάλι δικά σας εἶναι.

See also:

- C.C. Felton, Selections from Modern Greek Writers in Prose and Poetry. With Notes (Cambridge: John Bartlett, 1856), pp. 149 and 206-207

- Arnold Passow, Popularia Carmina Graeciae Recentioris (Leipzig: B.G. Teuber, 1860), pp. 146-147 (number 196)

- Margaret Alexiou, "The historical lament for the fall or destruction of cities," The Ritual Lament in Greek Tradition, 2nd ed. (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2002), pp. 83-101

- The Philological Crocodile, "Museum Closed: On the Desecration of the Hagia Sophia"

Saturday, July 25, 2020

The Bear and the Donkey

Beethoven, letter to Heinrich Joseph von Collin? (February, 1808?; tr. Emily Anderson):

I am so annoyed that all I desire is to be a bear so that as often as I were to lift my paw I could knock down some so-called great — — — ass.

Ich bin so verdrießlich, daß ich mir nichts wünsche als ein Bär zu seyn, um so oft ich meine Taze aufhöb, einen sogenanten großen — — — Esel zu Boden schlagen zu können.

Disinterestedness

Fustel de Coulanges, The Ancient City, tr. Willard Small (Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1874), p. 10:

To understand the truth about the Greeks and Romans, it is wise to study them without thinking of ourselves, as if they were entirely foreign to us; with the same disinterestedness, and with the mind as free, as if we were studying ancient India or Arabia.

Pour connaître la vérité sur ces peuples anciens, il est sage de les étudier sans songer à nous, comme s'ils nous étaient tout à fait étrangers, avec le même désintéressement et l'esprit aussi libre que nous étudierions l'Inde ancienne ou l'Arabie.

Friday, July 24, 2020

Facts and Interpretation

Jerzy Linderski, "Si Vis Pacem Para Bellum: Concepts of Defensive

Imperialism," Roman Questions: Selected Papers (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1995), pp. 1-31 (at 8-9):

For Roman facts are not waiting there to be collected; the act of picking them up is the act of choice and interpretation. No fact exists without an interpretation imposed upon it. For facts are like words in a dictionary; they are dead. In the real language words come to life only in enunciations; in the real world facts come to life only in the flow of history. And the flow of history, as we know it, flows from the ordering mind of the historian, ancient or modern. The tools of order are unexpressed philosophy and assumed terminology. Hence even the most extensive erudition and deepest knowledge of the quisquilia of epigraphy may still result in specious history. In order to understand or refute what a historian says, we must investigate his frame of mind. This appears to us a natural postulate with respect to our ancient forefathers, but the dissecting of the minds of our contemporary colleagues many would feel is a different matter: a task unbecoming a scholar and gentleman. Yet we are not questioning honesty; we are questioning philosophy. We are seeking premises unexpressed, unrealized, unsuspected.Id., pp. 13-14:

In books purporting to deal with History and not merely with isolated happenings it is well to read the preface; for in the preface the author reveals his motives and confesses his dreams.

Their Only Goal Is To Destroy

Friedrich Nietzsche, The Anti-Christ § 58 (tr. Judith Norman):

Christians are perfectly identical with anarchists: their only goal, their only instinct is to destroy. Just look at history: it proves this proposition with gruesome clarity. We just learned about a form of religious legislation whose goal was to 'eternalize' the supreme condition for a thriving life, a great organization of society; Christianity, by contrast, saw its mission as bringing this sort of an organization to an end because it led to a thriving life. In this society, the returns of reason from the long ages of experiment and uncertainty should have been invested for the greatest long-term advantage, and the greatest, richest, most perfect crop possible should have been harvested: but quite the opposite happened here, the harvest was poisoned overnight ... What stood as aere perennius, the imperium Romanum, the most magnificent form of organization ever to be achieved under difficult conditions, compared to which everything before or after has just been patched together, botched and dilettantish, — those holy anarchists made a 'piety' out of destroying 'the world', which is to say the imperium Romanum, until every stone was overturned, — until even the Germans and other thugs could rule over it ... The Christian and the anarchist: both are decadents, neither one can do anything except dissolve, poison, lay waste, bleed dry, both have instincts of mortal hatred against everything that stands, that stands tall, that has endurance, that promises life a future ... Christianity was the vampire of the imperium Romanum, — overnight, it obliterated the Romans' tremendous deed of laying the ground for a great culture that had time. — You still don't understand? The imperium Romanum that we know, that we are coming to know better through the history of the Roman provinces, this most remarkable artwork in the great style was a beginning, its design was calculated to prove itself over the millennia, —, nothing like it has been built to this day, nobody has even dreamed of building on this scale, sub specie aeterni! — This organization was stable enough to hold up under bad emperors: the accident of personalities cannot make any difference with things like this, — first principle of all great architecture. But it was not stable enough to withstand the most corrupt type of corruption, to withstand Christians ... This secretive worm that crept up to every individual under the cover of night, fog, and ambiguity and sucked the seriousness for true things, the instinct for reality in general right out of every individual, this cowardly, feminine, saccharine group gradually alienated the 'souls' from that tremendous structure, — those valuable, those masculine-noble natures that saw Rome's business as their own business, their own seriousness, their own pride. The priggish creeping around, the conventicle secrecy, dismal ideas like hell, like the sacrifice of the innocent, like the unio mystica in the drinking of blood, above all the slowly fanned flames of revenge, of Chandala revenge — that is what gained control over Rome....

To Wake the Dead

Jacob Burckhardt, The Civilisation of the Renaissance in Italy, tr. S.G.C. Middlemore (1878; rpt. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd., 1928), pp. 181-182:

Thanks very much to Kenneth Haynes for the following:

Nor was the enthusiasm for the classical past of Italy confined at this period to the capital. Boccaccio2 had already called the vast ruins of Baiae 'old walls, yet new for modern spirits;' and since this time they were held to be the most interesting sight near Naples. Collections of antiquities of all sorts now became common. Ciriaco of Ancona (d. 1457), who explained (1433) the Roman monuments to the Emperor Sigismund, travelled, not only through Italy, but through other countries of the old world, Hellas, and the islands of the Archipelago, and even parts of Asia and Africa, and brought back with him countless inscriptions and sketches. When asked why he took all this trouble, he replied, 'To wake the dead.'1John Edwin Sandys, A History of Classical Scholarship, Vol. II: From the Revival of Learning to the End of the Eighteenth Century (Cambridge: At the University Press, 1908), p. 40 (on Ciriaco of Ancona):

2 Boccaccio, Fiammetta, cap. 5. Opere, ed. Montier, vi.91.

1 His work, Cyriaci Anconitani Itinerarium, ed. Mehus, Florence, 1742. Comp. Leandro Alberti, Descriz. di tutta l'Italia, fol. 285.

In his unwearied endeavour to resuscitate the memorials of the past, he was fully conscious that his mission in life was 'to awake the dead'. He took a special pleasure in recalling an incident that once occurred while he was looking for antiques in a church at Vercelli. An inquisitive priest, who, on seeing him prowling about the church, ventured to ask him on what business he was bent, was completely mystified by the solemn reply:—'It is sometimes my business to awaken the dead out of their graves; it is an art that I have learnt from the Pythian oracle of Apollo'4.Cf. Biondo Flavio, Italy Illuminated, Vol. I: Books I-IV, tr. Jeffrey A. White (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2005 = I Tatti Renaissance Library, 20), pp. 260-261 (III.15):

4 Voigt, i 2843; cp. Jahn, 336.

Civibus ea civitas gravibus et honestis, in primis mercaturae deditis, sed maxime omnium servatae dudum libertatis gloria decoratur. Habetque nunc Franciscum Scalamontem et Nicolaum, iure consultos bonarum litterarum studiis ornatos, cum nuper amiserit Ciriacum, qui monumenta investigando vetustissima mortuos, ut dicere erat solitus, vivorum memoriae restituebat.

Ancona is notable for her serious and honest citizens, who are principally devoted to trade, but above all for her long-preserved liberty. Among the citizens nowadays are the jurisconsults Niccole and Francesco Scalamonti, distinguished for their literary attainments. But she has recently lost Cyriac of Ancona, who by his investigation of ancient monuments restored the dead to the memory of the living, as he used to put it.

Thanks very much to Kenneth Haynes for the following:

Worth quoting Cyriac's Latin?: "...mortuos quandoque ab Inferis suscitare Pythia illa inter vaticinia didici."Related posts:

Burckhardt gives the source (Itinerarium, 1742), just not the page (55). In context:

Sed enim inter Liguras nondum exacto biennio apud Vercellas antiquam ad Apenninos montes, & olim nobilem civitatem, & de qua Hieronymus senior ille noster suis epistolis in ea de septies percussa virgine particula mentionem habet, dum vetustis in sacris aedibus nostro de more aliquid verendae aeternitatis indagare coepissem, sacerdoti cuidam ignavo, quaenam mea ars esset interroganti ex tempore equidem respondi, mortuos quandoque ab Inferis suscitare Pythia illa inter vaticinia didici.

The Jerome is epist. 1.3. My guess about the "Pythia vaticinia" is that it refers to Cyriac's trip to Delphi.

If I've understood it ... :

Among the Ligurians about two years ago in the ancient town of Vercelli near the Apennines (both a once noble city and one which that elder Jerome of ours makes mention of in his letters in that section about the virgin struck seven times) while I was beginning to track, in my fashion, something within an old holy temple of awe-inspiring eternity, I replied at once to some ignorant priest, who was asking what my profession was: "I have learned among those Pythian prophecies to rouse the dead now and then from the underworld."

Thursday, July 23, 2020

Sumptuous Meals

Mark Twain's Own Autobiography: The Chapters from the North American Review (Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1990), pp. 113-114 (from Chapter XIII):

It was a heavenly place for a boy, that farm of my uncle John's. The house was a double log one, with a spacious floor (roofed in) connecting it with the kitchen. In the summer the table was set in the middle of that shady and breezy floor, and the sumptuous meals — well, it makes me cry to think of them. Fried chicken, roast pig, wild and tame turkeys, ducks and geese; venison just killed; squirrels, rabbits, pheasants, partridges, prairie-chickens; biscuits, hot batter cakes, hot buckwheat cakes, hot "wheat bread," hot rolls, hot corn pone; fresh corn boiled on the ear, succotash, butter-beans, string-beans, tomatoes, pease, Irish potatoes, sweet-potatoes; buttermilk, sweet milk, "clabber"; watermelons, musk-melons, cantaloups — all fresh from the garden — apple pie, peach pie, pumpkin pie, apple dumplings, peach cobbler — I can't remember the rest. The way that the things were cooked was perhaps the main splendor — particularly a certain few of the dishes. For instance, the corn bread, the hot biscuits and wheat bread, and the fried chicken. These things have never been properly cooked in the North — in fact, no one there is able to learn the art, so far as my experience goes. The North thinks it knows how to make corn bread, but this is gross superstition. Perhaps no bread in the world is quite as good as Southern corn bread, and perhaps no bread in the world is quite so bad as the Northern imitation of it. The North seldom tries to fry chicken, and this is well; the art cannot be learned north of the line of Mason and Dixon, nor anywhere in Europe.Related post: Food and Drink.

A Certain Type of Man

Xenophon, Hellenica 6.3.3 (tr. Carleton L. Brownson):

He was the sort of man to enjoy no less being praised by himself than by others.Hat tip: Alan Crease.

ἦν δ’ οὗτος οἷος μηδὲν ἧττον ἥδεσθαι ὑφ’ αὑτοῦ ἢ ὑπ’ ἄλλων ἐπαινούμενος.

Pliny the Elder

Arthur Schopenhauer, Parerga and Paralipomena, Vol. II, § 245 (tr. Adrian Del

Caro and Christopher Janaway):

Students and scholars of all kinds and every age as a rule are only focused on information, not on insight. They make it a point of honour to have information about everything, about all rocks, plants, battles, experiments and especially about every manner of book. It does not occur to them that information is a mere means to insight, having little or no value in itself, whereas it is the way of thinking that characterizes philosophical minds. Occasionally, when I consider the impressive erudition of these know-it-alls I say to myself: oh how little they have had to think about, in order to have been able to read so much! Even when it is reported of the elder Pliny that he was constantly reading, or having things read to him at the table, on trips, in the bath and so on, the question arises for me whether the man was so terribly lacking in thoughts of his own that those of others had to be incessantly transfused to him, just as a consommé is given to a consumptive to keep him alive. And neither his undiscriminating gullibility nor his unspeakably repulsive, incomprehensible, and paper-saving collectanea style does anything to give me a high opinion of his capacity to think for himself.Pliny the Younger, Letters 3.5.13-16 (to Baebius Macer; tr. John B. Firth):

Studierende und Studierte aller Art und jedes Alters gehn in der Regel nur auf Kunde aus; nicht auf Einsicht. Sie setzen ihre Ehre darin, von Allem Kunde zu haben, von allen Steinen, oder Pflanzen, oder Bataillen, oder Experimenten und sammt und sonders von allen Büchern. Daß die Kunde ein bloßes Mittel zur Einsicht sei, an sich aber wenig, oder keinen Werth habe, fällt ihnen nicht ein, ist hingegen die Denkungsart, welche den philosophischen Kopf charakterisirt. Bei der imposanten Gelehrsamkeit jener Vielwisser sage ich mir bisweilen: o, wie wenig muß doch Einer zu denken gehabt haben, damit er so viel hat lesen können! Sogar wenn vom alten Plinius berichtet wird, daß er beständig las, oder sich vorlesen ließ, bei Tische, auf Reisen, im Bade; so dringt sich mir die Frage auf, ob denn der Mann so großen Mangel an eigenen Gedanken gehabt habe, daß ihm ohne Unterlaß fremde eingeflößt werden mußten, wie dem an der Auszehrung Leidenden ein consommé, ihn am Leben zu erhalten. Und von seinem Selbstdenken mir hohe Begriffe zu geben ist weder seine urtheilslose Leichtgläubigkeit, noch sein unaussprechlich widerwärtiger, schwer verständlicher, papiersparender Kollektaneenstil geeignet.

In summer he used to rise from the dinner-table while it was still light; in winter always before the first hour had passed, as though there was a law obliging him to do so. Such was his method of living when up to the eyes in work and amid the bustle of Rome. When he was in the country the only time snatched from his work was when he took his bath, and when I say bath I refer to the actual bathing, for while he was being scraped with the strigil or rubbed down, he used to listen to a reader or dictate. When he was travelling he cut himself aloof from every other thought and gave himself up to study alone. At his side he kept a shorthand writer with a book and tablets, who wore mittens on his hands in winter, so that not even the sharpness of the weather should rob him of a moment, and for the same reason, when in Rome, he used to be carried in a litter. I remember that once he rebuked me for walking, saying, "If you were a student, you could not waste your hours like that," for he considered that all time was wasted which was not devoted to study.

surgebat aestate a cena luce, hieme intra primam noctis et tamquam aliqua lege cogente. haec inter medios labores urbisque fremitum. in secessu solum balinei tempus studiis eximebatur: cum dico balinei, de interioribus loquor; nam dum destringitur tergiturque, audiebat aliquid aut dictabat. in itinere quasi solutus ceteris curis, huic uni vacabat: ad latus notarius cum libro et pugillaribus, cuius manus hieme manicis muniebantur, ut ne caeli quidem asperitas ullum studii tempus eriperet; qua ex causa Romae quoque sella vehebatur. repeto me correptum ab eo, cur ambularem: 'poteras' inquit 'has horas non perdere'; nam perire omne tempus arbitrabatur, quod studiis non impenderetur.

Deification of Laughter

Stephen Halliwell, Greek Laughter: A Study of Cultural Psychology from Homer to Early Christianity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), pp. 44-45:

It may seem initially counterintuitive that of all ancient Greek communities it should have been the Spartans, with their reputation for being the hardest, severest of peoples, among whom laughter — or perhaps one should write Laughter — was allegedly the object of religious cult, uniquely so within the mainstream public religion of Greek city-states.118 According to Plutarch, this cult was marked by a small statue of the deity (Gelos) dedicated by the great Spartan culture-hero, Lycurgus. Plutarch relates this circumstance (which is perhaps the more credible for having been derived from the early Hellenistic Spartan historian Sosibius) by way of stressing that the Spartans, for all their toughness, did in fact make use of laughter in their dealings with one another. They did so, on his account, both to make more palatable the exchanges of personal criticism that were an integral part of their ideological 'consciousness raising', and, by Lycurgus' own design, as an occasional relief, at symposia and elsewhere, from the otherwise relentless toil of their austere way of life. This picture of Laconian mores suggests that laughter counted as something psychologically and socially necessary to the militarised regimen of the Spartiates, yet as a factor which existed in firmly controlled counterpoint to the harsh, uncompromising demands of that regimen. Elsewhere, in his life of Cleomenes, Plutarch tells us that the Spartans had shrines dedicated to 'fear, death, laughter and other such elemental experiences (pathēmata)', a formulation which prima facie makes laughter one of the basic coordinates (physical, psychological and social) of a rather darkly coloured map of existence.119 In the case of fear, however, so Plutarch explains, this was because the Spartans actually recognised the communal value of something that might otherwise easily be framed in wholly negative terms. If that is right, then in the case of laughter we might conjecture that the Spartans had a nervous but canny reverence for an impulse which counted as a force of nature (manifesting itself, like fear, in keenly somatic form) and was deemed sufficiently dangerous to be treated as at least quasi-divine. Difficult though it is to penetrate into the Spartan mentality, the idea of its deification of Gelos makes best sense as the expression of an attempt neither to keep laughter at bay nor to encourage its unbridled celebration, but to harness its power to the cohesion of a scrupulously regulated society of equals.Plutarch, Life of Lycurgus 25.2 (tr. Bernadotte Perrin):

118 The nearest parallel is the festival of laughter at Thessalian Hypatia posited (fictionally?) by Apul. Met. 2.31, 3.11: see Milanezi (1992), esp. 134–41. The painting of personified Gelos at Philostr. maj. Imag. 1.25.3 (quoted as epigraph to Ch. 3) is not testimony to religious practice: such a figure appears nowhere in regular Dionysiac cult.

119 Spartan statue/shrine to Laughter: Plut. Lyc. 25.2 (Sosibius FGrH 595 F19, where Jacoby's commentary moots a misunderstanding of the face of an archaic statue), Cleom. 9; cf. Choric. Apol. Mim. 91–2 (Foerster). For Spartan 'worship' of personified laughter, fear, etc., see Richer (1999) 92–7, 106–7, Richer (2005) 111–12. David (1989) provides an excellent survey of the whole subject of Spartan laughter; cf. Milanezi (1992) 127–31. The views ascribed to the Spartan Chilon should not be taken as peculiar to his culture: cf. 29 above, with ch. 6, 265–7.

For not even Lycurgus himself was immoderately severe; indeed, Sosibius tells us that he actually dedicated a little statue of Laughter, and introduced seasonable jesting into their drinking parties and like diversions, to sweeten, as it were, their hardships and meagre fare.Plutarch, Life of Cleomenes 9.1 (tr. Bernadotte Perrin):

οὐδὲ γὰρ αὐτὸς ἦν ἀκράτως αὐστηρὸς ὁ Λυκοῦργος· ἀλλὰ καὶ τὸ τοῦ Γέλωτος ἀγαλμάτιον ἐκεῖνον ἱδρύσασθαι Σωσίβιος ἱστορεῖ, τὴν παιδιὰν ὥσπερ ἥδυσμα τοῦ πόνου καὶ τῆς διαίτης ἐμβαλόντα κατὰ καιρὸν εἰς τὰ συμπόσια καὶ τᾶς τοιαύτας διατριβάς.

Now, the Lacedaemonians have temples of Death, Laughter, and that sort of thing, as well as of Fear.

ἔστι δὲ Λακεδαιμονίοις οὐ Φόβου μόνον, ἀλλὰ καί Θανάτου καί Γέλωτος καί τοιούτων ἄλλων παθημάτων ἱερά.

Sweet

Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English People 5.24 (tr. J.E. King):

I have taken delight always either to learn, or to teach, or to write.

semper aut discere, aut docere, aut scribere dulce habui.

Wednesday, July 22, 2020

Against the Stoics

Dio Cassius 65.13.1a (tr. Earnest Cary):

Mucianus made a great number of remarkable statements to Vespasian against the Stoics, asserting, for instance, that they are full of empty boasting, and that if one of them lets his beard grow long, elevates his eyebrows, wears his coarse brown mantle thrown back over his shoulder and goes barefooted, he straightway lays claim to wisdom, bravery and righteousness, and gives himself great airs, even though he may not know either his letters or how to swim, as the saying goes. They look down upon everybody and call a man of good family a mollycoddle, the low-born slender-witted, a handsome person licentious, an ugly person a simpleton, the rich man greedy, and the poor man servile.

Μουκιανὸς πρὸς Βεσπασιανὸν κατὰ τῶν στωικῶν πλεῖστά τε εἶπε καὶ θαυμάσια, ὡς ὅτι αὐχήματος κενοῦ εἰσι πεπληρωμένοι, κἂν τὸν πώγωνά τις αὐτῶν καθῇ καὶ τὰς ὀφρύας ἀνασπάσῃ τό τε τριβώνιον ἀναβάληται καὶ ἀνυπόδητος βαδίσῃ, σοφὸς εὐθὺς ἀνδρεῖος δίκαιός φησιν εἶναι, καὶ πνεῖ ἐφ᾿ ἑαυτῷ μέγα, κἂν τὸ λεγόμενον δὴ τοῦτο μήτε γράμματα μήτε νεῖν ἐπίστηται. καὶ πάντας ὑπερορῶσι, καὶ τὸν μὲν εὐγενῆ τηθαλλαδοῦν τὸν δὲ ἀγενῆ σμικρόφρονα, καὶ τὸν μὲν καλὸν ἀσελγῆ τὸν δὲ αἰσχρὸν εὐφυᾶ, τὸν δὲ πλούσιον πλεονέκτην τὸν δὲ πένητα δουλοπρεπῆ καλοῦσι.

Tearing Down versus Building Up

Edmund Burke (1729-1797), Reflections on the Revolution in France, in his Works, Vol. IV (London: Francis & John Rivington, 1852), p. 289:

Rage and frenzy will pull down more in half an hour, than prudence, deliberation, and foresight can build up in a hundred years. The errors and defects of old establishments are visible and palpable. It calls for little ability to point them out; and where absolute power is given, it requires but a word wholly to abolish the vice and the establishment together. The same lazy but restless disposition, which loves sloth and hates quiet, directs the politicians, when they come to work for supplying the place of what they have destroyed. To make everything the reverse of what they have seen is quite as easy as to destroy. No difficulties occur in what has never been tried. Criticism is almost baffled in discovering the defects of what has not existed; and eager enthusiasm and cheating hope have all the wide field of imagination, in which they may expatiate with little or no opposition.Id., p. 291:

It is undoubtedly true, though it may seem paradoxical; but in general, those who are habitually employed in finding and displaying faults, are unqualified for the work of reformation: because their minds are not only unfurnished with patterns of the fair and good, but by habit they come to take no delight in the contemplation of those things. By hating vices too much, they come to love men too little. It is therefore not wonderful, that they should be indisposed and unable to serve them. From hence arises the complexional disposition of some of your guides to pull everything in pieces.

The Motion of the Ocean

Eusebius, Praeparatio Evangelica 14.18.32 (tr. Ugo Zilioli):

Among his [Aristippus the Elder's] hearers, there was his daughter Arete, who had a son and called him Aristippus. He was introduced to philosophy by her and for that he was termed 'mother-taught'. He clearly defined pleasure as the end, inserting into his doctrine the concept of pleasure related to motion. For he said, there are three conditions of our temperament: one, in which we are in pain, is like a storm at sea; another, in which we experience pleasure and which can be compared to a gentle wave, for pleasure is a gentle movement, similar to a fair wind; and the third is an intermediate condition, in which we experience neither pain nor pleasure, which is like a calm. He said we have perception of these affections alone.

τούτου γέγονεν ἀκουστὴς σὺν ἄλλοις καὶ ἡ θυγάτηρ αὐτοῦ Ἀρήτη˙ ἥτις γεννήσασα παῖδα ὠνόμασεν Ἀρίστιππον, ὃς ὑπαχθεὶς ὑπ' αὐτῆς εἰς λόγους φιλοσοφίας μητροδίδακτος ἐκλήθη˙ ὃς καὶ σαφῶς ὡρίσατο τέλος εἶναι τὸ ἡδέως ζῆν, ἡδονὴν ἐντάττων τὴν κατὰ κίνησιν. τρεῖς γὰρ ἔφη καταστάσεις εἶναι περὶ τὴν ἡμετέραν σύγκρασιν˙ μίαν μὲν καθ' ἣν ἀλγοῦμεν, ἐοικυῖαν τῷ κατὰ θάλασσαν χειμῶνι˙ ἑτέραν δὲ καθ' ἣν ἡδόμεθα, τῷ λείῳ κύματι ἀφομοιουμένην, εἶναι γὰρ λείαν κίνησιν τὴν ἡδονήν, οὐρίῳ παραβαλλομένην ἀνέμῳ˙ τὴν δὲ τρίτην μέσην εἶναι κατάστασιν, καθ' ἣν οὔτε ἀλγοῦμεν οὔτε ἡδόμεθα, γαλήνῃ παραπλησίαν οὖσαν. τούτων δὴ καὶ ἔφασκε τῶν παθῶν μόνων ἡμᾶς τὴν αἴσθησιν ἔχειν.

Tuesday, July 21, 2020

Street Names

John Kelly, The Great Mortality (New York: HarperCollins, 2005), pp. 16-17:

I noticed a misprint on p. 23 of Kelly's book:

By the early fourteenth century so much filth had collected inside urban Europe that French and Italian cities were naming streets after human waste. In medieval Paris, several street names were inspired by merde, the French word for "shit." There were rue Merdeux, rue Merdelet, rue Merdusson, rue des Merdons, and rue Merdiere—as well as a rue du Pipi.Maybe twenty-first century San Francisco should follow suit.

I noticed a misprint on p. 23 of Kelly's book:

In 1631, a historian named Johannes Isaacus Pontanus, perhaps thinking of Seneca's use of the Latin term for Black Death—Arta mors—to describe an outbreak of epidemic disease in Rome, claimed that the phrase had been current during the fourteenth-century mortality.For Arta read Atra.

Labels: noctes scatologicae, typographical and other errors

Alone

Petrarch (1304-1374), Rerum Familiarum Libri 8.7.19-20 (tr. Aldo S. Bernardo):

Where are our sweet friends now, where are their beloved faces, where are their soothing words, where is their mild and pleasant conversation? What thunderbolt destroyed all those things, what earthquake overturned them, what storm overcame them, what abyss absorbed them? We used to be a crowd, now we are almost alone. We must seek new friendships. But where or for what reason when the human species is almost extinct and the end, as I hope, is near? Why pretend, dear brother, for we are indeed alone.I wouldn't translate auguror as I hope.

ubi dulces nunc amici, ubi sunt amati vultus, ubi verba mulcentia, ubi mitis et iocunda conversatio? quod fulmen ista consumpsit, quis terre motus evertit, que tempestas demersit, que abyssus absorbuit? stipati eramus, prope iam soli sumus. nove amicitie contrahende sunt. unde autem sive ad quid, humano genere pene extincto, et proximo, ut auguror, rerum fine? sumus, frater, sumus — quid dissimulem? — vere soli.

Live for Today

Aristippus, fragment 208 Mannebach = Aelian, Historical Miscellany 14.6 (tr. Robin Hard):

Aristippos was thought to have made a very sound point when he urged people not to worry afterwards about things that have gone by, or worry in advance about those that are yet to come. For such an attitude is a sign of confidence and gives proof of a cheerful frame of mind. He recommended that one should concentrate on the present day, and indeed on the very part of it in which one is acting and thinking. For only the present, he said, truly belongs to us, and not what has passed by or what we are anticipating: for the one is gone and done with, and it is uncertain whether the other will come to be.

πάνυ σφόδρα ἐρρωμένως ἐῴκει λέγειν ὁ Ἀρίστιππος παρεγγυῶν τοῖς ἀνθρώποις μήτε τοῖς παρελθοῦσιν ἐπικάμνειν μήτε τῶν ἐπιόντων προκάμνειν· εὐθυμίας γὰρ δεῖγμα τὸ τοιοῦτο καὶ ἵλεω διανοίας ἀπόδειξις. προσέταττε δὲ ἐφ᾿ ἡμέρᾳ τὴν γνώμην ἔχειν καὶ αὖ πάλιν τῆς ἡμέρας ἐπ᾿ ἐκείνῳ τῷ μέρει, καθ᾿ ὃ ἕκαστος ἢ πράττει τι ἢ ἐννοεῖ. μόνον γὰρ ἔφασκεν ἡμέτερον εἶναι τὸ παρόν, μήτε δὲ τὸ φθάνον μήτε τὸ προσδοκώμενον· τὸ μὲν γὰρ ἀπολωλέναι, τὸ δὲ ἄδηλον εἶναι εἴπερ ἔσται.

All Would Be Right With the World

Isaac Bashevis Singer, The Penitent (New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1983), p. 37:

I bought a newspaper, and as I turned the pages I found everything there that I wanted to escape from: wars, glorification of revolution, murders, rapes, politicians' cynical promises, lying editorials, acclaim of stupid books, dirty plays and films. The newspaper paid tribute to every possible kind of idolatry and spat at truth. According to the editors, if the voters would only choose the President they recommended, and put into effect this or the other reform, all would be right with the world.

Laws

Tacitus, Germania 19 (tr. William Peterson):

Good habits have more force with them than good laws elsewhere.Tacitus, Annals 3.27 (tr. J.C. Yardley):

plusque ibi boni mores valent quam alibi bonae leges.

Laws were most numerous when the state was most corrupt.

corruptissima re publica plurimae leges.

Sunday, July 19, 2020

A Hymn

[John Wesley,] Queries Humbly Proposed to the Right Reverend and Right Honourable Count Zinzendorf (London: J. Robinson and T. James, 1755), pp. 29-30:

Do you own or disown that Hymn? (I shrink at repeating such words)This seems to refer to Zinzendorf's Gedichte number 2010, stanzas 8-9:

"Member full of MysteryAnd that to our Saviour, "May thy first holy Wound anoint me for the conjugal Business, on that Member of my Body which is for the Benefit of my Wife? — The rest I cannot repeat. Were ever such Words put together before, from the Foundation of the World?

Which holily gives and chastly receives

The conjugal Ointments for Jesus' sake;

Mayst thou be blessed and anointed?"

Und geheimnißvolles glied! das die ehelichen salben Jesus halben heilig gibt und keusch empfäht im gebet, in dem von dem Erz-erbarmen selbst erfundenen umarmen, wenn man kirchen-saamen sä't;Ovid addresses his membrum virile in less flattering terms in Amores 3.7.69-72 (tr. G.P. Goold):

Sey gesegnet und gesalbt mit dem blut, das unserm manne dort entranne: fühle heisse zärtlichkeit, zu der seit, die fürs Lamms gemahlin offen, seit der speer hineingetroffen, das object der eheleut.

Lie down there, you shamefaced creature, worthless part of me: I have been tricked by promises like this before. You deceive your master; through you I have been caught defenceless, and suffered a painful and humiliating reverse.Encolpius also castigates his membrum virile for its impotence in Petronius, Satyricon 132. See Gareth Schmeling, A Commentary on the Satyrica of Petronius (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), p. 507:

quin istic pudibunda iaces, pars pessima nostri?

sic sum pollicitis captus et ante tuis.

tu dominum fallis; per te deprensus inermis

tristia cum magno damna pudore tuli.

The mentula of course cannot reply, but we do find a speaking penis at Horace Serm. 1.2.68-70. On the motif of literary addresses of a man to his penis: G. Salanitro (1971-2) 448; Adams (1982) 30 calls it an 'implicit personification', as does Richlin (1992a) 116; Ovid Am. 3.7.69; Priapea 83.14-45; AP 5.47, 12.216, 232. On 'Klage über Impotenz', see Höschele (2006) 129-35; Holzberg (2005).

Saturday, July 18, 2020

Controversy

Here are some excerpts from Edward Gibbon, A Vindication

of Some Passages in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Chapters

of the History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.

Introduction:

Introduction:

Perhaps it may be necessary to inform the Public, that not long since an Examination of the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Chapters of the History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire was published by Mr. Davis. He styles himself a Bachelor of Arts, and a Member of Baliol College in the University of Oxford. His title-page is a declaration of war, and in the prosecution of his religious crusade, he assumes a privilege of disregarding the ordinary laws which are respected in the most hostile transactions between civilized men or civilized nations. Some of the harshest epithets in the English language are repeatedly applied to the historian, a part of whose work Mr. Davis has chosen for the object of his criticism. To this author Mr. Davis imputes the crime of betraying the confidence and seducing the faith of those readers, who may heedlessly stray in the flowery paths of his diction, without perceiving the poisonous snake that lurks concealed in the grass. Latet anguis in herbâ.VIII (on Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 8.14):

[....]

I have never affected, indeed I have never understood, the stoical apathy, the proud contempt of criticism, which some authors have publicly professed. Fame is the motive, it is the reward, of our labours; nor can I easily comprehend how it is possible that we should remain cold and indifferent with regard to the attempts which are made to deprive us of the most valuable object of our possessions, or at least of our hopes.

[....]

The reasons which justified my silence were obvious and forcible: the respectable nature of the subject itself, which ought not to be rashly violated by the rude hand of controversy; the inevitable tendency of dispute, which soon degenerates into minute and personal altercation; the indifference of the Public for the discussion of such questions as neither relate to the business nor the amusement of the present age. I calculated the possible loss of temper and the certain loss of time, and considered, that while I was laboriously engaged in a humiliating task, which could add nothing to my own reputation, or to the entertainment of my readers, I must interrupt the prosecution of a work which claimed my whole attention, and which the Public, or at least my friends, seemed to require with some impatience at my hands.

[....]

Every animal employs the note, or cry, or howl, which is peculiar to its species; every man expresses himself in the dialect the most congenial to his temper and inclination, the most familiar to the company in which he has lived, and to the authors with whom he is conversant; and while I was disposed to allow that Mr. Davis had made some proficiency in Ecclesiastical Studies, I should have considered the difference of our language and manners as an unsurmountable bar of separation between us. Mr. Davis has over-leaped that bar, and forces me to contend with him on the very dirty ground which he has chosen for the scene of our combat.

[....]

The defence of my own honour is undoubtedly the first and prevailing motive which urges me to repel with vigour an unjust and unprovoked attack; and to undertake a tedious vindication, which, after the perpetual repetition of the vainest and most disgusting of the pronouns, will only prove that I am innocent; and that Mr. Davis, in his charge, has very frequently subscribed his own condemnation.

[....]

Perhaps, before we separate, a moment to which I most fervently aspire, Mr. Davis may find that a mature judgment is indispensably requisite for the successful execution of any work of literature, and more especially of criticism. Perhaps he will discover, that a young student, who hastily consults an unknown author, on a subject with which he is unacquainted, cannot always be guided by the most accurate reference to the knowledge of the sense, as well as to the sight of the passage which has been quoted by his adversary.

Let him examine the chapter on which he founds his accusation. If in that moment his feelings are not of the most painful and humiliating kind, he must indeed be an object of pity!IX:

I disdain to add a single reflection; nor shall I qualify the conduct of my adversary with any of those harsh epithets, which might be interpreted as the expressions of resentment, though I should be constrained to use them as the only words in the English language, which could accurately represent my cool and unprejudiced sentiments.XI:

Nothing but the angry vehemence with which these charges are urged, could engage me to take the least notice of them. In themselves they are doubly contemptible; they are trifling, and they are false.XII:

The Writer who aspires to the name of Historian, is obliged to consult a variety of original testimonies, each of which, taken separately, is perhaps imperfect and partial. By a judicious re-union and arrangement of these dispersed materials, he endeavours to form a consistent and interesting narrative. Nothing ought to be inserted which is not proved by some of the witnesses; but their evidence must be so intimately blended together, that as it is unreasonable to expect that each of them should vouch for the whole, so it would be impossible to define the boundaries of their respective property.XVI:

My readers, if any readers have accompanied me thus far, must be satisfied, and indeed satiated, with the repeated proofs which I have made of the weight and temper of my adversary's weapons. They have, in every assault, fallen dead and lifeless to the ground: they have more than once recoiled, and dangerously wounded the unskilful hand that had presumed to use them.XVII:

I cannot profess myself very desirous of Mr. Davis's acquaintance; but if he will take the trouble of calling at my house any afternoon when I am not at home, my servant shall show him my library, which he will find tolerably well furnished with the useful authors, ancient as well as modern, ecclesiastical as well as profane, who have directly supplied me with the materials of my History.XX:

The historian must indeed be generous, who will conceal, by his own disgrace, that of his country, or of his religion. Whatever subject he has chosen, whatever persons he introduces, he owes to himself, to the present age, and to posterity, a just and perfect delineation of all that may be praised, of all that may be excused, and of all that must be censured. If he fails in the discharge of his important office, he partially violates the sacred obligations of truth, and disappoints his readers of the instruction which they might have derived from a fair parallel of the vices and virtues of the most illustrious characters.

[....]

Juvenal might have read his satire against women in a circle of Roman ladies, and each of them might have listened with pleasure to the amusing description of the various vices and follies, from which she herself was so perfectly free. The moralist, the preacher, the ecclesiastical historian, enjoy a still more ample latitude of invective; and as long as they abstain from any particular censure, they may securely expose, and even exaggerate, the sins of the multitude.

[....]

Before I return these sheets to the press, I must nor forget an anonymous pamphlet, which, under the title of A Few Remarks, etc. was published against my History in the course of the last summer. The unknown writer has thought proper to distinguish himself by the emphatic, yet vague, appellation of A GENTLEMAN: but I must lament that he has not considered, with becoming attention, the duties of that respectable character. I am ignorant of the motives which can urge a man of a liberal mind, and liberal manners, to attack without provocation, and without tenderness, any work which may have contributed to the information, or even to the amusement, of the Public. But I am well convinced, that the author of such a work, who boldly gives his name and his labours to the world, imposes on his adversaries the fair and honourable obligation of encountering him in open day-light, and of supporting the weight of their assertions by the credit of their names. The effusions of wit, or the productions of reason, may be accepted from a secret and unknown hand. The critic who attempts to injure the reputation of another, by strong imputations which may possibly be false, should renounce the ungenerous hope of concealing behind a mask the vexation of disappointment, and the guilty blush of detection.

[....]

It would be an endless discussion (endless in every sense of the word), were I to examine the cavils which start up and expire in every page of this criticism, on the inexhaustible topic of opinions, characters, and intentions. Most of the instances which are here produced, are of so brittle a substance that they fall in pieces as soon as they are touched...

Think

Aristophanes, Clouds 700-705 (tr. Jeffery Henderson):

Now think and contemplate,The same, tr. Cyril Bailey:

twirl yourself every way

and concentrate; and whenever you hit a dead end,

quickly jump to another

line of thought; and let sweet-spirited sleep

be remote from your eyes.

φρόντιζε δὴ καὶ διάθρει

πάντα τρόπον τε σαυτὸν

στρόβει πυκνώ-

σας. ταχὺς δ', ὅταν εἰς ἄπορον

πέσῃς, ἐπ' ἄλλο πήδα

νόημα φρενός· ὕπνος δ᾿ ἀπέ-

στω γλυκύθυμος ὀμμάτων.

Ponder and think with a resolute brain.M.W. Humphreys ad loc.:

Twisting and turning and twisting again!

If in a puzzle you happen to stick,

Hop like a flea to a different trick.

Sleep the consoler be far from thy brow.

Presumption

Edmund Burke (1729-1797), Reflections on the Revolution in France, in his Works, Vol. IV (London: Francis & John Rivington, 1852), p. 280:

I cannot conceive how any man can have brought himself to that pitch of presumption, to consider his country as nothing but carte blanche, upon which he may scribble whatever he pleases. A man full of warm, speculative benevolence may wish his society otherwise constituted than he finds it; but a good patriot, and a true politician, always considers how he shall make the most of the existing materials of his country. A disposition to preserve, and an ability to improve, taken together, would be my standard of a statesman. Everything else is vulgar in the conception, perilous in the execution.

Friday, July 17, 2020

The True Craftsman

H.J. Massingham, "Samuel Rockall," in A Mirror of England: An Anthology of the Writings of H.J. Massingham (1888-1952) (Hartland: Green Books, 1988), pp. 70-77 (at 71-72):

The true craftsman controls and executes all the processes of his craft from raw originals to the finished product, no matter how many they be. He is thus divided by a cleavage absolute from the one-man-one-bolt system of modern, minutely subdivided industry. That is why the rural master-man remains by the law of his being close to nature. He is not merely surrounded by nature; he not only takes his tools and materials from nature, but he repeats the ordered unfoldings of nature from the seed to the flower, from the grain to the ear, from alpha to omega. This is the secret of good craftsmanship and the condition of its blossoming, that the man shall take the fruits of the earth from the hands of nature, and with his own hands transform them into the final form he destines for them, to be at once useful for the needs of his fellows and pleasurable to their eyes.

Unicus Vir

G.W. Bowersock, "Ronald Syme—A Brief Tribute," in T.J. Luce and A.J. Woodman, edd., Tacitus and the Tacitean Tradition (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993), pp. xiii-xv (at xiv):

He supervised only a half-dozen doctoral candidates in his long career, and those of us fortunate enough to be in that number have long recognized that what we most owed to Syme was the steady support to grow in our own way and the luminous example of learning and dedication he set for us. Syme was never a destructive critic. He wrote no notes on thesis drafts. He simply discussed the work in a civilized and collegial colloquy during long walks in Christ Church meadow. Even when he had to correct a plain mistake, he found a generously oblique way to do it. Once at a tender age I was unaware that St. Jerome and Hieronymus were not actually two different people. When Syme perceived my error, he said to me quietly and tactfully, "unicus uir."

The Authorship of the Germania

This is a footnote to Bold Theories About Tacitus. A.N. Sherwin-White, "Tacitus and the Barbarians," in his Racial Prejudice in Ancient Rome (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1967), pp. 33-61, expresses doubt about the Tacitean authorship of the treatise Germania, at p. 34:

According to https://blogger.googleblog.com/2020/05/a-better-blogger-experience-on-web.html:

In Tacitus' historical books, and in the Germania, if its author is in truth Tacitus, there is a change of attitude due to the passage of time.Id., p. 42. n. 1:

If the authorship of the Germania is not to be doubted, the difference of emphasis is all the more remarkable.Sherwin-White (passim) refers to "the author of the Germania" or "the author." He gives no reason for his doubt and cites no other authorities. The only other scholar known to me who subscribes to this theory is Leo Wiener, Contributions Towards a History of Arabico-Gothic Culture, Vol. III: Tacitus' Germania & Other Forgeries (Philadelphia: Innes & Sons, 1920).

According to https://blogger.googleblog.com/2020/05/a-better-blogger-experience-on-web.html:

We'll be moving everyone to the new interface over the coming months. Starting in late June, many Blogger creators will see the new interface become their default, though they can revert to the old interface by clicking "Revert to legacy Blogger" in the left-hand navigation. By late July, creators will no longer be able to revert to the legacy Blogger interface.Because of this forced change, I am now having problems composing and publishing blog posts. If I can no longer use the legacy Blogger interface that I've been using since 2004, I may stop blogging altogether, or else move this blog to a different platform.

Thursday, July 16, 2020

Thermopylae

William Golding, "The Hot Gates," The Hot Gates and Other Occasional Pieces (London: Faber and Faber, 1965), pp. 3-12 (at 11-12):

I came to myself in a great stillness, to find I was standing by the little mound. This is the mound of Leonidas, with its dust and rank grass, its flowers and lizards, its stones, scruffy laurels and hot gusts of wind. I knew now that something real happened here. It is not just that the human spirit reacts directly and beyond all argument to a story of sacrifice and courage, as a wine glass must vibrate to the sound of the violin. It is also because, way back and at the hundredth remove, that company stood in the right line of history. A little of Leonidas lies in the fact that I can go where I like and write what I like. He contributed to set us free.The Greek, from Herodotus 7.228:

Climbing to the top of that mound by the uneven, winding path, I came on the epitaph, newly cut in stone. It is an ancient epitaph though the stone is new. It is famous for its reticence and simplicity — has been translated a hundred times but can only be paraphrased:

'Stranger, tell the Spartans that we behaved as they would wish us to, and are buried here.'

ὦ ξεῖν᾿, ἀγγέλλειν Λακεδαιμονίοις ὅτι τῇδε

κείμεθα τοῖς κείνων ῥήμασι πειθόμενοι.

Knowledge of Ancient Greek

Michael Clarke, "Semantics and Vocabulary," in Egbert J. Bakker, ed., A Companion to the Ancient Greek Language (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010), pp. 120-133 (at 120):

I do not really know Ancient Greek, nor do any of the contributors to this Companion. To claim knowledge of a language, you must be a member of its speech-community, open to the possibility that the categories of its grammar and vocabulary may mold and be molded by the structures of your thoughts and worldview. This cannot happen if we engage with the language only in a library. Knowledge of language depends on acquaintance; knowledge by description is not enough.I know only one person capable of ordering a meal in Ancient Greek. On the one occasion when he took me and his charming wife and daughters to a restaurant, however, he did not speak Ancient Greek. You know who you are, my friend.

This leads to an uncomfortable paradox. If I learnt enough Arabic or Chinese to order a meal in a restaurant, and if I went to Riyadh or Beijing and did so, I would have a better claim on that language than I have on Homer's mother tongue after many years of daily engagement with his words.

Inherited or Imitated Way of Walking

I once speculated that in the recognition scene of Aeschylus, Libation Bearers 205-210 (cf. Euripides, Electra 532-537), Electra saw in the footprints of her brother Orestes some "distinctive, recognizable gait, for example, the pressure of toe and heel, the distance between the steps, the direction of the toes, etc....Perhaps Electra and Orestes shared a distinctive gait learned in early childhood from their father Agamemnon." I recently came across a passage in Apuleius' Metamorposes (2.2) which mentions the similarity in gait between a mother and son (tr. E.J. Kenney):

But she looked at me and said: 'Yes, he's his sainted mother Salvia all over — it shows in his breeding and modesty. And his looks — it's uncanny, he couldn't be more like her: moderately tall, slim but muscular, nice complexion, a natural blond, simple hairstyle, eyes grey but alert and bright, really like an eagle's, a blooming countenance, a graceful but unaffected walk.'

at illa optutum in me conversa: 'en', inquit 'sanctissimae Salviae matris generosa probitas, sed et cetera corporis execrabiliter ad regulam sunt congruentia: inenormis proceritas, succulenta gracilitas, rubor temperatus, flavum et inadfectatum capillitium, oculi caesii quidem, sed vigiles et in aspectu micantes, prorsus aquilini, os quoquoversum floridum, speciosus et immeditatus incessus.'

Attainments

Anthony Hope, The Prisoner of Zenda, Chapter I:

I had picked up a good deal of pleasure and a good deal of knowledge. I had been to a German school and a German university, and spoke German as readily and perfectly as English; I was thoroughly at home in French; I had a smattering of Italian and enough Spanish to swear by. I was, I believe, a strong, though hardly fine swordsman and a good shot. I could ride anything that had a back to sit on; and my head was as cool a one as you could find, for all its flaming cover.The Memoirs of Alexandre Dumas (Père), Vol. II, tr. A.F. Davidson (London: W.H. Allen Co. Limited, 1891), pp. 26-27:

"I must first know what you can do."

"Oh, nothing very great."

"Come, come! you know something of Mathematics?"

"No, General."

"You have, at any rate, some ideas of Algebra—Geometry—Physics?"

He paused between each word, and at each word I felt a fresh blush rising to my face, and the perspiration trickling faster and faster from my forehead. It was the first time that I had been brought thus face to face with my own ignorance.

"No, General," I stammered out, "I know nothing of any of those."

"Do you know Latin or Greek?"

"Latin—a little; Greek—not at all."

"Can you speak any living language?"

"Italian."

"Do you understand the keeping of accounts?"

"Not in the least."

I was on the rack, and he himself was visibly suffering for me.

"Oh, General!" I cried, in tones which seemed to make a strong impression on him, "my education is utterly deficient, and—shame on me for it—it is to-day and from this moment that I see it for the first time. Ah, but I will make it up, I give you my word, I will and some day—some day—I will answer 'Yes' to all the questions which I have now answered with 'No.'"

"But meanwhile, my friend, have you anything to live on?"

"Nothing—nothing! General," I replied, overwhelmed by the consciousness of my helplessness.

The General looked at me with profound commiseration.

"And yet," he said, "I do not like to abandon you."

"No, General; for you would not be abandoning me only! I am a dunce and an idler, it is true; but my mother who counts on me—my mother whom I promised to get myself a post—my mother should not be punished for my ignorance and idleness."

"Give me your address," he said; "I will think over what can be done for you. There, write it at this desk."

He handed me the pen he had just been using. I took the pen, looked at it—the ink was not yet dry upon it—and then, shaking my head, I gave it back to him.

"No," I said, "I will not write with your pen; it would be a profanation."

"What a child you are!" he said, with a smile; "stay, here is an unused one."

I began to write, the General looking on at me. Barely had I written my name when he clapped his hands together, and exclaimed:

"We are saved!"

"Saved! Why? how?"

"You write a capital hand."

I dropped my head. I could no longer bear the load of my shame. "A capital handwriting"—that was all I possessed! This hall-mark of incapacity—how exactly it suited me! "A capital handwriting!" So one day I might succeed in becoming a copying-clerk; this was my future! Gladly would I have cut off my right arm.

Progress

H.J. Massingham, "Coke of Norfolk," in A Mirror of England: An Anthology of the Writings of H.J. Massingham (1888-1952) (Hartland: Green Books, 1988), pp. 122-124 (at 124):

There is an uneasy suspicion abroad to-day that "progress" is "a tale Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, Signifying nothing." Yet this is too pessimistic: progress does mean something, and what I take it to mean is a sudden longing, in the midst of confusion and tribulation, for the good things, the kind traditions, the old rhythms of life that the age has wantonly thrown away in pursuit of the power and the wealth that turn to dust as soon as in the hand.

Wednesday, July 15, 2020

Learning Disabilities

Aristophanes, Clouds 628-631 (tr. Benjamin Bickley Rogers):

Never, no never have I seen a clown

So helpless, and forgetful, and absurd!

Why if he learns a quirk or two he clean

Forgets them ere he has learnt them.

οὐκ εἶδον οὕτως ἄνδρ᾿ ἄγροικον οὐδαμοῦ

οὐδ᾿ ἄπορον οὐδὲ σκαιὸν οὐδ᾿ ἐπιλήσμονα,

ὅστις σκαλαθυρμάτι᾿ ἄττα μικρὰ μανθάνων

ταῦτ᾿ ἐπιλέλησται πρὶν μαθεῖν.

631 ταῦτ᾿ codd.: πάντ᾿ Blaydes

Boredom

H.J. Massingham, "Boredom," in A Mirror of England: An Anthology of the Writings of H.J. Massingham (1888-1952) (Hartland: Green Books, 1988), p. 175:

I have yet to meet a bored countryman. Worried, yes, anxious, continually persecuted by ignorant officials, overworked, even despairing, bitterly cynical about the future, even resolved to leave the land because of bad conditions if he is a labourer, of insecurity if he is a farmer, of crushing taxation if he is a good squire. But boredom is not a word that can be found in the true countryman's dictionary. Why? Because except on the most highly mechanized farms all countrymen follow ill or well Voltaire' s maxim of cultivating their gardens. They take, that is to say, pleasure in and exert skill on their jobs. But when, say, 90 per cent of modern workers have been deprived by the machine of skill and interest and pleasure in their daily work, they are suffering from the disgraceful sin of being bored. This explains at once why, when they are released from the boredom of their daily work, they depend upon the mechanical hedonism of being amused by others. But it does not release them from the disgraceful sin of being bored. This is the nemesis of modern urban civilization which has all but killed rural England: it is delivered over to the disgraceful sin of being bored.Related post: Work.

Intellectual Rubbish

Bertrand Russell, "An Outline of Intellectual Rubbish," Unpopular Essays (London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd, 1921), pp. 95-145 (at 95):

Man is a rational animal—so at least I have been told. Throughout a long life, I have looked diligently for evidence in favor of this statement, but so far I have not had the good fortune to come across it, though I have searched in many countries spread over three continents. On the contrary, I have seen the world plunging continually further into madness. I have seen great nations, formerly leaders of civilization, led astray by preachers of bombastic nonsense. I have seen cruelty, persecution, and superstition increasing by leaps and bounds, until we have almost reached the point where praise of rationality is held to mark a man as an old fogey regrettably surviving from a bygone age.Id. (at 100):

I am sometimes shocked by the blasphemies of those who think themselves pious—for instance, the nuns who never take a bath without wearing a bathrobe all the time. When asked why, since no man can see them, they reply: "Oh, but you forget the good God." Apparently they conceive of the Deity as a Peeping Tom, whose omnipotence enables Him to see through bathroom walls, but who is foiled by bathrobes.Id. (at 114):

Every powerful emotion has its own myth-making tendency. When the emotion is peculiar to an individual, he is considered more or less mad if he gives credence to such myths as he has invented. But when an emotion is collective, as in war, there is no one to correct the myths that naturally arise. Consequently in all times of great collective excitement unfounded rumors obtain wide credence.Id. (at 122):

There is no nonsense so arrant that it cannot be made the creed of the vast majority by adequate governmental action.Id. (at 129):

When one reads of the beliefs of savages, or of the ancient Babylonians and Egyptians, they seem surprising by their capricious absurdity. But beliefs that are just as absurd are still entertained by the uneducated even in the most modem and civilized societies.Id. (at 136):

If an opinion contrary to your own makes you angry, that is a sign that you are subconsciously aware of having no good reason for thinking as you do. If some one maintains that two and two are five, or that Iceland is on the equator, you feel pity rather than anger, unless you know so little of arithmetic or geography that his opinion shakes your own contrary conviction. The most savage controversies are those about matters as to which there is no good evidence either way. Persecution is used in theology, not in arithmetic, because in arithmetic there is knowledge, but in theology there is only opinion. So whenever you find yourself getting angry about a difference of opinion, be on your guard; you will probably find, on examination, that your belief is going beyond what the evidence warrants.Id. (at 136-137):

A good way of ridding yourself of certain kinds of dogmatism is to become aware of opinions held in social circles different from your own. When I was young, I lived much outside my own country in France, Germany, Italy, and the United States. I found this very profitable in diminishing the intensity of insular prejudice. If you cannot travel, seek out people with whom you disagree, and read a newspaper belonging to a party that is not yours. If the people and the newspaper seem mad, perverse, and wicked, remind yourself that you seem so to them. In this opinion both parties may be right, but they cannot both be wrong. This reflection should generate a certain caution.Id. (at 143):

Obloquy is, to most men, more painful than death; that is one reason why, in times of collective excitement, so few men venture to dissent from the prevailing opinion.

Tuesday, July 14, 2020

An Early Greek Epitaph

Inscriptiones Graecae IX,1 521 (Acarnania, possibly Anactorium, 6th century B.C.?), tr. Paul Friedländer and Herbert B. Hoffleit, Epigrammata: Greek Inscriptions in Verse from the Beginnings to the Persian Wars (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1948), p. 74 (number 64, Greek as printed there):

See also Jesper Svenbro, Phrasikleia: An Anthropology of Reading in Ancient Greece, tr. Janet Lloyd (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1993), pp. 36-37.

This monument by the road shall be called Procleida's, who died fighting for his own land.αὐτῶ = αὐτοῦ, βαρνάμενος = μαρνάμενος. On phrases resembling θάνε βαρνάμενος see Nathan T. Arrington, "Inscribing Defeat: The Commemorative Dynamics of the Athenian Casualty Lists," Classical Antiquity 30.2 (October, 2011) 179-212 (at 187-188, esp. 188):

Προκλείδας τόδε σᾶμα κεκλήσεται ἐνγὺς ὁδοῖο,

ὃς περὶ τᾶς αὐτῶ γᾶς θάνε βαρνάμενος.

In each case the present participle marnamenoi is coupled with a verb for dying in the aorist to describe how the men died: with courage. The value placed on fighting until the very end of one's life recalls the rhetoric of manhood evoked in epic poetry, such as Kallinos' admonition, "Let each one, with his last breath, hurl his spear."62Peter Allan Hansen, ed., Carmina Epigraphica Graeca Saeculorum VIII–V a. Chr. n., (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1983), pp. 77-78: