Friday, March 31, 2023

Warning to Polymaths

Democritus, fragment 169 (tr. Kathleen Freeman):

Do not try to understand everything, lest you become ignorant of everything.

μὴ πάντα ἐπίστασθαι προθυμέο, μὴ πάντων ἀμαθὴς γένῃ.

Discussion

Walter Bagehot (1826-1877), Literary Studies, Vol. III (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1913), pp. 208-209:

The process by which truth wins in discussion is this,—certain strong and eager minds embrace original opinions, seldom all wrong, never quite true, but of a mixed sort, part truth, part error; these they inculcate on all occasions and on every side, and gradually bring the cooler sort of men to a hearing of them. These cooler people serve as quasi-judges, while the more eager ones are a sort of advocates; a Court of Inquisition is sitting perpetually, investigating, informally and silently, but not ineffectually, what, on all great subjects of human interest, is truth and error. There is no sort of infallibility about the court; often it makes great mistakes, most of its decisions are incomplete in thought and imperfect in expression. Still, on the whole, the force of evidence keeps it right. The truth has the best of the proof, and therefore wins most of the judgments. The process is slow, far more tedious than the worst Chancery suit. Time in it is reckoned not by days, but by years, or rather by centuries. Yet, on the whole, it creeps along, if you do not stop it. But all is arrested if persecution begins,—if you have a coup d'état, and let loose soldiers on the court; for it is perfect chance which litigant turns them in, or what creed they are used to compel men to believe.

Live by the Good Old Standards

Plautus, Trinummus 281-300 (Philto to Lysiteles; tr. Paul Nixon):

My boy, I wish you to hold no converse with reprobates, in the streets or in the forum, none whatever. I know this age and what its moral standards are: a bad man wants a good man to be bad, and so be like himself. These bad men muddle our standards, mix them up; that wide-maw tribe, the grasping, the mean, the envious, regard things sacred as profane, public as private. It gripes me, it torments me, it is what I harp on day and night that you are to guard against. The only thing they think it wrong to lay their hands on is something that is out of reach. As for the rest—nab it and bag it, clear out and lie low! Ugh! When I see all this it brings tears to my eyes that I have lasted till such a race was born. Why not have hied me hence before to join the great majority? Why, these men praise the standards of our sires, and then be-sully what they so bepraise. My boy, I can dispense with your adopting such practices and letting them contaminate your character. Live as I live, by the good old standards, and carry out the precepts that you get from me. I cannot stand those filthsome, chaotic standards that disgrace good citizens. Take these injunctions of mine to heart, and many a blessing will you have within you.

nolo ego cum improbis te viris, gnate mi,

neque in via, neque in foro necullum sermonem exsequi.

novi ego hoc saeculum moribus quibu' siet:

malus bonum malum esse volt, ut sit sui similis;

turbant, miscent mores mali: rapax, avarus, invidus 285

sacrum profanum, publicum privatum habent, hiulca gens.

haec ego doleo, haec sunt quae me excruciant, haec dies noctes[que] tibi canto ut caveas.

quod manu non queunt tangere tantum fas habent quo manus apstineant,

cetera: rape trahe, fuge late—lacrumas haec mihi quom video eliciunt, 289-290

quia ego ad hoc genus hominum duravi. quin priu' me ad plures penetravi?

nam hi mores maiorum laudant, eosdem lutitant quos conlaudant.

hisce ego de artibu' gratiam facio, ne[u] colas neve imbuas ingenium.

meo modo et moribu' vivito antiquis, quae ego tibi praecipio, ea facito. 295-296

nihil ego istos moror faeceos mores, turbidos, quibu' boni dedecorant se. 297-298

haec tibi si mea imperia capesses, multa bona in pectore consident. 299-300

292 lutitant Ritschl: latitant codd.

A Pernicious Affectation

Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve, "Brief Mention," American Journal of Philology 33.2 (1912) 227-241 (at 237):

One pernicious affectation is a certain tip-tilted sniffing at great authors whom it is our business to try to understand and not to censure.

The Senate

Ronald Syme, "Greeks Invading the Roman Government," in his Roman Papers, IV (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988), pp. 1-20 (at 16):

[T]he Senate...harboured a mass of mediocrities worthy of most of the business there transacted.

Thursday, March 30, 2023

World Government

Aelius Aristides, Orations 26.60 (vol. 2, p. 108 Keil; tr. James H. Oliver):

Neither sea nor intervening continent are bars to citizenship, nor are Asia and Europe divided in their treatment here. In your empire all paths are open to all. No one worthy of rule or trust remains an alien, but a civil community of the World has been established as a Free Republic under one, the best, ruler and teacher of order; and all come together as into a common civic center, in order to receive each man his due.

καὶ οὔτε θάλαττα διείργει τὸ μὴ εἶναι πολίτην οὔτε πλῆθος τὰς ἐν μέσῳ χώρας, οὐδ' Ἀσία καὶ Εὐρώπη διῄρηται ἐνταῦθα· πρόκειται δ' ἐν μέσῳ πᾶσι πάντα· ξένος δ' οὐδεὶς ὅστις ἀρχῆς ἢ πίστεως ἄξιος, ἀλλὰ καθέστηκε κοινὴ τῆς γῆς δημοκρατία ὑφ' ἑνὶ τῷ ἀρίστῳ ἄρχοντι καὶ κοσμητῇ, καὶ πάντες ὥσπερ εἰς κοινὴν ἀγορὰν συνίασι τευξόμενοι τῆς ἀξίας ἕκαστοι.

Destroyed by Our Own Hands

Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities 6.53.1-2 (speech of Agrippa Menenius; tr. Earnest Cary):

[1] The natives have here their wives, children, parents, and many others that are dear to them, to serve as pledges; yes, and there is their fondness for the soil that reared them, a passion that is implanted in all men and not to be eradicated; but as for this multitude which we propose to invite here, this people without roof or home, if they should take up their abode with us having none of these pledges here, in defence of what blessing would they care to face dangers, unless one were to promise to give them portions of land and some part or other of the city, after first dispossessing the present owners — things we refuse to grant to our own citizens who have often fought in their defence? And possibly they might not be content with even these grants alone, but would also insist upon an equal share of honours, of magistracies, and of all the other advantages with the patricians. [2] If, therefore, we do not grant them every one of their demands, shall we not have them as our enemies when they fail to obtain what they ask? And if we grant their demands, our country and our constitution will be lost, destroyed by our own hands.

[1] τῷ μέν τ᾽ ἐπιχωρίῳ καὶ τέκνων καὶ γυναικῶν καὶ γονέων καὶ πολλῶν ἄλλων σωμάτων οἰκείων ὅμηρά ἐστιν ἐνθάδε, καὶ αὐτοῦ νὴ Δία τοῦ θρέψαντος αὐτοὺς ἐδάφους ὁ πόθος, ἀναγκαῖος ὢν ἅπασι καὶ οὐκ ἐξαιρετός· ὁ δ᾽ ἐπίκλητός γε οὑτοσὶ καὶ ἐπίσκηνος ὄχλος, εἰ γένοιτο ἡμῖν σύνοικος, οὐδενὸς αὐτῷ τούτων ἐνθάδε ὄντος, ὑπὲρ τίνος ἂν ἀξιώσειε κινδυνεύειν ἀγαθοῦ, εἰ μή τις αὐτῷ γῆς τε ὑπόσχοιτο μέρη δώσειν καὶ πόλεως μοῖραν ὅσην δή τινα τοὺς νῦν κυρίους αὐτῶν ἀφελόμενος, ὧν οὐκ ἀξιοῦμεν τοῖς πολλάκις ἀγωνισαμένοις ὑπὲρ αὐτῶν πολίταις μεταδιδόναι; καὶ ἴσως ἂν οὐδὲ τούτοις ἀρκεσθείη δοθεῖσι μόνοις, ἀλλὰ καὶ τιμῶν καὶ ἀρχῶν καὶ τῶν ἄλλων ἀγαθῶν ἐξ ἴσου τοῖς πατρικίοις ἀξιώσειε μεταλαμβάνειν. [2] οὐκοῦν εἰ μὲν οὐκ ἐπιτρέψομεν ἕκαστα τῶν αἰτουμένων, ἐχθροῖς τοῖς μὴ τυγχάνουσι χρησόμεθα; εἰ δὲ συγχωρήσαιμεν, ἡ πατρὶς ἡμῖν οἰχήσεται καὶ ἡ πολιτεία πρὸς ἡμῶν αὐτῶν καταλυομένη.

Autocracy

Ronald Syme, "Greeks Invading the Roman Government," in his Roman Papers, IV (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988), pp. 1-20 (at 11):

An autocrat is not omnipotent. There are facts he cannot fight against, groups and pressures he cannot resist.

Wednesday, March 29, 2023

A Great Replacement

Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities 6.52.1 (Agrippa Menenius speaking ironically; tr. Earnest Cary):

The commonwealth is very likely threatened with no other danger as yet than a change of inhabitants, a matter of no serious consequence; and it would be very easy for us to receive into the body politic a multitude of labourers and clients from every nation and place.

τῇ πόλει δ᾽ οὐδὲν ἕτερον ἤδη που κινδυνεύεται ἢ μεταβολή, πρᾶγμα οὐ χαλεπόν, κατὰ πολλήν τ᾽ ἂν ἡμῖν εὐπέτειαν ἐκ παντὸς ἔθνους καὶ τόπου θῆτά τε καὶ πελάτην ὄχλον εἰσδέξασθαι γένοιτο.

Truth and Falsehood

Dio Chrysostom, Discourses 11.1-2 (tr. J.W. Cohoon):

[1] I am almost certain that while all men are hard to teach, they are easy to deceive. They learn with difficulty—if they do learn anything—from the few that know, but they are deceived only too readily by the many who do not know, and not only by others but by themselves as well. For the truth is bitter and unpleasant to the unthinking, while falsehood is sweet and pleasant. [2] They are, I fancy, like men with sore eyes—they find the light painful, while the darkness, which permits them to see nothing, is restful and agreeable. Else how would falsehood often prove mightier than the truth, if it did not win its victories through pleasure?

[1] οἶδα μὲν ἔγωγε σχεδὸν ὅτι διδάσκειν μὲν ἀνθρώπους ἅπαντας χαλεπόν ἐστιν, ἐξαπατᾶν δὲ ῥᾴδιον. καὶ μανθάνουσι μὲν μόγις, ἐάν τι καὶ μάθωσι, παρ᾿ ὀλίγων τῶν εἰδότων, ἐξαπατῶνται δὲ τάχιστα ὑπὸ πολλῶν τῶν οὐκ εἰδότων, καὶ οὐ μόνον γε ὑπὸ τῶν ἄλλων, ἀλλὰ καὶ αὐτοὶ ὑφ᾿ αὑτῶν. τὸ μὲν γὰρ ἀληθὲς πικρόν ἐστι καὶ ἀηδὲς τοῖς ἀνοήτοις, τὸ δὲ ψεῦδος γλυκὺ καὶ προσηνές. [2] ὥσπερ οἶμαι καὶ τοῖς νοσοῦσι τὰ ὄμματα τὸ μὲν φῶς ἀνιαρὸν ὁρᾶν, τὸ δὲ σκότος ἄλυπον καὶ φίλον, οὐκ ἐῶν βλέπειν. ἢ πῶς ἂν ἴσχυε τὰ ψεύδη πολλάκις πλέον1 τῶν ἀληθῶν, εἰ μὴ δι᾿ ἡδονὴν ἐνίκα;

Word Frequencies

George Kingsley Zipf, "Frequency of Occurrence of Words in Plautus' Aulularia, Mostellaria, Pseudolus, and Trinummus," Selected Studies of the Principle of Relative Frequency in Language (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1932), pp. 31-51 (at 31):

Separate entries for homo and hominem (plus other oblique cases further down), faciam and facere, etc., are jarring to my pedantic mind, although I can understand why Zipf did it—he was counting syllables as well as words, after all. The statistics disconcert splitters (because of homonyms) as well as lumpers.

Six-Axe Man

Ronald Syme, "Greeks Invading the Roman Government," in his Roman Papers, IV (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988), pp. 1-20 (at 2):

Nowadays "fascist" is overused and practically meaningless. For the sake of variety at least, can we use "six-axe man" instead?

Under the rule of the imperial Republic, the Greek lands had endured manifold disasters and tribulation, to mention only the constant drain of wealth to Italy. The matter can be illustrated by brief recourse to the balance of trade, to what are called 'invisible exports'. Italy sent out governors and soldiers, financiers and tax-gatherers, and Italy drew benefit in return, with enhanced prosperity (though not for all classes of the population). Those exports, be it added, were all too visible throughout the Eastern countries: legionaries, rapacious bankers, and the governor parading in the purple mantle of war, preceded by lictors who bore axes on their rods. The earliest Greek term for the mandatory who carries the imperium is 'a six-axe man' (ἑξαπέλεκυς). To the imperial people, by contrast, the emblems of power convey beauty as well as terror: in the phrase of the poet Lucretius, 'pulchros fasces saevasque secures'.ἑξαπέλεκυς first occurs in Polybius (cf. Latin sexfascalis). The quotation from Lucretius comes from De Rerum Natura 5.1234.

Nowadays "fascist" is overused and practically meaningless. For the sake of variety at least, can we use "six-axe man" instead?

Tuesday, March 28, 2023

Earnest Believers

Walter Bagehot (1826-1877), Literary Studies, Vol. III (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1913), p. 206:

Since the time of Carlyle, "earnestness" has been a favourite virtue in literature, and it is customary to treat this wish to twist other people's belief into ours as if it were a part of the love of truth. And in the highest minds so it may be. But the mass of mankind have, as I hold, no such fine motive. Independently of truth or falsehood, the spectacle of a different belief from ours is disagreeable to us, in the same way that the spectacle of a different form of dress and manners is disagreeable. A set of schoolboys will persecute a new boy with a new sort of jacket; they will hardly let him have a new-shaped penknife. Grown-up people are just as bad, except when culture has softened them. A mob will hoot a foreigner who looks very unlike themselves. Much of the feeling of "earnest believers" is, I believe, altogether the same. They wish others to think as they do, not only because they wish to diffuse doctrinal truth, but also and much more because they cannot bear to hear the words of a creed different from their own.

Demigods

Simonides, in Page, Poetae Melici Graeci, number 523 (tr. Jenny Strauss Clay):

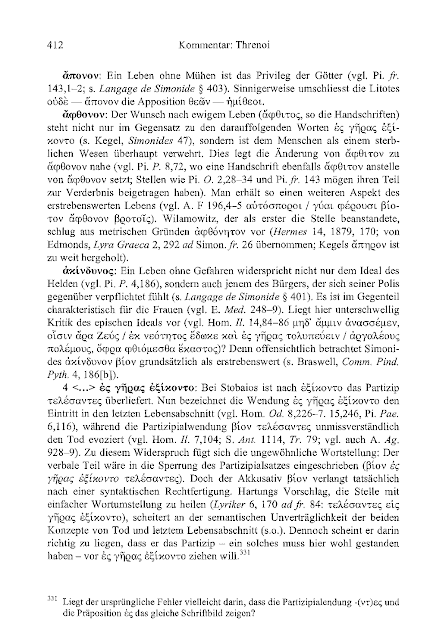

Not even those who once lived before us,Orlando Poltera, Simonides lyricus. Testimonia und Fragmente. Einleitung, kritische Ausgabe, Übersetzung und Kommentar (Basel: Schwabe Verlag, 2008), pp. 411-412 (click once or twice to enlarge):

the demigods, sons born from our lords, the gods,

brought to completion a life without toil or decline or danger,

and arrived at old age.

†οὐδὲ γὰρ οἳ πρότερόν ποτ᾿ ἐπέλοντο,

θεῶν δ᾿ ἐξ ἀνάκτων ἐγένονθ᾿ υἷες ἡμίθεοι,

ἄπονον οὐδ᾿ ἄφθιτον οὐδ᾿ ἀκίνδυνον βίον

ἐς γῆρας ἐξίκοντο τελέσαντες.†

3 ἄφθιτον codd.: ἀφθόνητον Wilamowitz: ἄφθονον Poltera

Monday, March 27, 2023

The Destruction of Troy

Aeschylus, Agamemnon 524-528 (tr. Herbert Weir Smyth):

Hat tip: Eric Thomson.

Oh give him goodly greeting, as is meet and right, since he hath uprooted Troy with the mattock of Zeus, the Avenger, wherewith her soil has been uptorn. Demolished are the altars and the shrines of her gods; and the seed of her whole land hath been wasted utterly.John Dewar Denniston and Denys Page on line 527:

ἀλλ' εὖ νιν ἀσπάσασθε, καὶ γὰρ οὖν πρέπει,

Τροίαν κατασκάψαντα τοῦ δικηφόρου 525

Διὸς μακέλλῃ, τῇ κατείργασται πέδον.

βωμοὶ δ' ἄιστοι καὶ θεῶν ἱδρύματα,

καὶ σπέρμα πάσης ἐξαπόλλυται χθονός.

527 del. Wilhelm Gotthilf Salzmann, Observationum in Aeschyli Agamemnonem Specimen (Berlin: G. Reimer, 1823), pp. 10-11

Some have rejected this line as an interpolation, on the grounds that (1) it interrupts the metaphor begun in 526 and continued in 528 (σπέρμα); (2) it resembles a line found elsewhere in Aeschylus (Pers. 811 βωμοὶ δ' ἄιστοι δαιμόνων θ' ἱδρύματα; (3) the Herald ought not to boast of an action so shocking to the religious feelings of the Hellenes: 'to the poet and his contemporaries the destruction of holy places by the enemy seemed an unparalleled atrocity' (Fraenkel). Of these arguments the third alone seems considerable. It must, however, be observed that Clytemnestra made it clear (338 ff.) that there was reason to fear that the army might commit just this kind of sacrilege : and here we are told that they did commit it. Without this line, the question raised by 338 ff. would be nowhere answered. Moreover it seems unlikely that the poet would allow his Herald to exaggerate so grossly as to say that the land was utterly devastated, reduced to a ploughed field, no seed left in the soil, without referring to the fact (if it was one) that the temples, altars, shrines, and the like were left intact. If nothing whatever is said about the holy places, the strength of the Herald's language is such that the Chorus is bound to infer (and so are we, who have wanted an answer to the question raised in 338 ff.) that they are included in the tale of total ruin.Cf. Exodus 34:13 (KJV):

But ye shall destroy their altars, break their images, and cut down their groves.Related post: The Buttock of Zeus.

Hat tip: Eric Thomson.

Degrees of Closeness and Remoteness

Cicero, On Duties 1.17.53-55 (tr. Walter Miller):

[53] Then, too, there are a great many degrees of closeness or remoteness in human society. To proceed beyond the universal bond of our common humanity, there is the closer one of belonging to the same people, tribe, and tongue, by which men are very closely bound together; it is a still closer relation to be citizens of the same city-state; for fellow-citizens have much in common—forum, temples, colonnades, streets, statutes, laws, courts, rights of suffrage, to say nothing of social and friendly circles and diverse business relations with many.

But a still closer social union exists between kindred. Starting with that infinite bond of union of the human race in general, the conception is now confined to a small and narrow circle. [54] For since the reproductive instinct is by Nature's gift the common possession of all living creatures, the first bond of union is that between husband and wife; the next, that between parents and children; then we find one home, with everything in common. And this is the foundation of civil government, the nursery, as it were, of the state. Then follow the bonds between brothers and sisters, and next those of first and then of second cousins; and when they can no longer be sheltered under one roof, they go out into other homes, as into colonies. Then follow between these, in turn, marriages and connections by marriage, and from these again a new stock of relations; and from this propagation and after-growth states have their beginnings. The bonds of common blood hold men fast through good-will and affection; [55] for it means much to share in common the same family traditions, the same forms of domestic worship, and the same ancestral tombs.

[53] gradus autem plures sunt societatis hominum. ut enim ab illa infinita discedatur, propior est eiusdem gentis, nationis, linguae, qua maxime homines coniunguntur; interius etiam est eiusdem esse civitatis; multa enim sunt civibus inter se communia, forum, fana, porticus, viae, leges, iura: iudicia, suffragia, consuetudines praeterea et familiaritates multisque cum multis res rationesque contractae.

artior vero colligatio est societatis propinquorum; ab illa enim immensa societate humani generis in exiguum angustumque concluditur. [54] nam cum sit hoc natura commune animantium, ut habeant libidinem procreandi, prima societas in ipso coniugio est, proxima in liberis, deinde una domus, communia omnia; id autem est principium urbis et quasi seminarium rei publicae. sequuntur fratrum coniunctiones, post consobrinorum sobrinorumque, qui cum una domo iam capi non possint, in alias domos tamquam in colonias exeunt. sequuntur conubia et affinitates, ex quibus etiam plures propinqui; quae propagatio et suboles origo est rerum publicarum. sanguinis autem coniunctio et benivolentia devincit homines et caritate; [55] magnum est enim eadem habere monumenta maiorum, eisdem uti sacris, sepulcra habere communia.

A City Divided

Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities 6.36.1 (tr. Earnest Cary):

For we are living apart from one another, as you see, and inhabit two cities, one of which is ruled by poverty and necessity, and the other by satiety and insolence; but modesty, order and justice, by which alone any civil community is preserved, remain in neither of these cities.

διῳκίσμεθα γὰρ ὡς ὁρᾶτε καὶ δύο πόλεις ἔχομεν, τὴν μὲν μίαν ὑπὸ πενίας τε καὶ ἀνάγκης ἀρχομένην, τὴν δ᾽ ὑπὸ κόρου καὶ ὕβρεως. αἰδὼς δὲ καὶ κόσμος καὶ δίκη, ὑφ᾽ ὧν ἅπασα πολιτικὴ κοινωνία σώζεται, παρ᾽ οὐδετέρᾳ μένει τῶν πόλεων.

Ancient Truth

Walter Bagehot (1826-1877), Literary Studies, Vol. III (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1913), p. 129:

It is much in every generation to state the ancient truth in the manner which that generation requires; to state the old answer to the old difficulty; to transmit, if not discover; convince, if not invent; to translate into the language of the living, the truths first discovered by the dead.

Sunday, March 26, 2023

A World of Illusion

George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950), The Political Madhouse in America and Nearer Home (London: Constable & Co, 1933), pp. 40-41:

That is to say, financiers live in a world of illusion. They count on something which they call the capital of the country which has no existence. Every five dollars they count as a hundred dollars; and that means that every financier, every banker, every stockbroker, is 95 per cent. a lunatic. And it is in the hands of these lunatics that you leave the fate of your country!

Death

Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities 6.9.6 (tr. Earnest Cary):

Death, indeed, is decreed to all men, both the cowardly and the brave; but an honourable and a glorious death comes to the brave alone.ὀφείλεται = is owed. Cf. A Debt Owed. Cf. also Homer, Iliad 12.322-328 (Sarpedon speaking to Glaucon; tr. Peter Green):

ἀποθανεῖν μὲν γὰρ ἅπασιν ἀνθρώποις ὀφείλεται, κακοῖς τε καὶ ἀγαθοῖς· καλῶς δὲ καὶ ἐνδόξως μόνοις τοῖς ἀγαθοῖς.

Ah, my friend, if the two of us could escape from this war,

and be both immortal and ageless for all eternity,

then neither would I myself be among the foremost fighters

nor would I send you out into battle that wins men honor;

but now—since come what may the death-spirits around us

are myriad, something no mortal can flee or avoid—

let's go on, to win ourselves glory, or yield it to others.

ὦ πέπον εἰ μὲν γὰρ πόλεμον περὶ τόνδε φυγόντε

αἰεὶ δὴ μέλλοιμεν ἀγήρω τ᾽ ἀθανάτω τε

ἔσσεσθ᾽, οὔτέ κεν αὐτὸς ἐνὶ πρώτοισι μαχοίμην

οὔτέ κε σὲ στέλλοιμι μάχην ἐς κυδιάνειραν· 325

νῦν δ᾽ ἔμπης γὰρ κῆρες ἐφεστᾶσιν θανάτοιο

μυρίαι, ἃς οὐκ ἔστι φυγεῖν βροτὸν οὐδ᾽ ὑπαλύξαι,

ἴομεν ἠέ τῳ εὖχος ὀρέξομεν ἠέ τις ἡμῖν.

The Essence of Life

Walter Bagehot (1826-1877), Literary Studies, Vol. III (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1913), p. 71:

Legislative Assemblies, leading articles, essay eloquence—such are good—very good,—useful—very useful. Yet they can be done without. We can want them. Not so with all things. The selling of figs, the cobbling of shoes, the manufacturing of nails,—these are the essence of life. And let whoso frameth a Constitution of his country think on these things.

With Books for My Only Friends

D.A. Bingham, A Selection from the Letters and Despatches of the First Napoleon, Vol. I (London: Chapman and Hall, 1884), p. 22:

On reporting himself at Auxonne, Napoleon declared that he had twice attempted to pass the straits and had twice been driven back by stress of weather, and produced certificates to this effect. Not only were his excuses accepted, but the Chevalier de Lance, by ante-dating his return, procured him three months' pay, which was a matter of importance to the needy lieutenant, who occupied a chamber which was nearly bare, and which in the way of furniture had only a miserable bed without curtains, a table covered with books and papers, and two chairs. Brother Louis was obliged to sleep on the floor in an adjoining closet.Related posts:

Twenty years later, when King Louis fled from Holland, Napoleon exclaimed to Caulaincourt: "Abdicate without warning me! Run away to Westphalia as if flying from a tyrant! My brother injure instead of aiding me! That Louis I educated on my pay of a lieutenant. God knows at the expense of what privations I found means to send money to pay my brother's schooling! Do you know how I managed? By never entering a café or going into society; by eating dry bread, and brushing my own clothes so that they might last the longer. I lived like a bear, in a little room, with books for my only friends, and when, thanks to abstinence, I had saved up a few crowns, I rushed off to the bookseller's shop and visited his coveted shelves.....These were the joys and debaucheries of my youth."

Saturday, March 25, 2023

Insecurity

Pindar, Pythian Odes 4.272-273 (tr. John Sandys):

For, even for the feeble, it is an easy task to shake a city to its foundation, but it is indeed a sore struggle to set it in its place again.Commentators compare Theognis 845-846 (tr. Dorothea Wender):

ῥᾴδιον μὲν γὰρ πόλιν σεῖσαι καὶ ἀφαυροτέροις·

ἀλλ' ἐπὶ χώρας αὖτις ἕσσαι δυσπαλὲς

δὴ γίνεται.

A man's good luck can easily be spoiled;Or, if Bergk's conjecture is adopted:

But to improve bad luck is difficult.

εὖ μὲν κείμενον ἄνδρα κακῶς θέμεν εὐμαρές ἐστιν,

εὖ δὲ θέμεν τὸ κακῶς κείμενον ἀργαλέον.

485 ἄνδρα codd: ἄστυ Bergk

A town in a good condition is easy to destroy,Related post: Easier to Tear Down Than to Build.

but it is hard to set aright one in a bad condition.

They Won't Stand for It

Walter Bagehot (1826-1877), Literary Studies, Vol. III (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1913), p. 65:

Men won't stand being cut, being ridiculed, being detested, being despised, daily and for ever, and that for measures which their own understandings disapprove of.

Wild Nature

Thomas Mann, The Magic Mountain, chapter 6 (tr. James E. Woods):

Born a stranger to remote, wild nature, the child of civilization is much more open to her grandeur than are her own coarse sons, who have been at her mercy from infancy and whose intimacy with her is more level-headed. They know next to nothing of the religious awe with which the novice approaches her, eyebrows raised, his whole being tuned to its depths to receive her, his soul in a state of constant, thrilled, timid excitement.

Das Kind der Zivilisation, fern und fremd der wilden Natur von Hause aus, ist ihrer Größe viel zugänglicher als ihr rauher Sohn, der, von Kindesbeinen auf sie angewiesen, in nüchterner Vertraulichkeit mit ihr lebt. Dieser kennt kaum die religiöse Furcht, mit der je ner, die Augenbrauen hochgezogen, vor sie tritt und die sein ganzes Empfindungsverhältnis zu ihr in der Tiefe bestimmt, eine beständige fromme Erschütterung und scheue Erregung in seiner Seele unterhält.

Friday, March 24, 2023

Great Curves

G.K. Chesterton (1874-1936), "On Pigs as Pets," The Uses of Diversity: A Book of Essays (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1921), pp. 97-104 (at 99-100):

The actual lines of a pig (I mean a really fat pig) are among the loveliest and most luxurious in nature, the pig has the same great curves, swift and yet heavy, which see in rushing water or in rolling cloud....Now, there is no point of view from which really corpulent pig is not full of sumptuous and satisfying curves....In short, he has that fuller, subtler and more universal kind of shapeliness which the unthinking (gazing at pigs and distinguished journalists) mistake for mere absence of shape. For fatness itself is a valuable quality. While it creates admiration in the onlookers, it creates modesty in the possessor.George Morland (1763-1804), In Front of the Sty:

Samon

[Warning: X-rated.]

Panel leg with a costumed reveller named Samon, on a tripod exaleiptron, ca. 570–560/550 B.C., in Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, inv. 3364, from Victoria Sabetai and Christina Avronidaki, "The Six's Technique in Boiotia: Regional Experiments in Technique and Iconography," Hesperia 87.2 (April-June 2018) 311-385 (at 314, figure 1:b, photograph by I. Luckert): Id. (at 338):

Panel leg with a costumed reveller named Samon, on a tripod exaleiptron, ca. 570–560/550 B.C., in Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, inv. 3364, from Victoria Sabetai and Christina Avronidaki, "The Six's Technique in Boiotia: Regional Experiments in Technique and Iconography," Hesperia 87.2 (April-June 2018) 311-385 (at 314, figure 1:b, photograph by I. Luckert): Id. (at 338):

Samon (Fig. 1:b) is an enigmatic character, best regarded as a costumed performer.160 The figure combines the traits of a satyr and a komast, as attested by his hairy bodice with appended large genitalia and his human face without snub profile or equine ears.161 The kindred nature of the early satyr and the komast is iconographically confirmed in Boiotia by their simultaneous presence on two of the panel legs of a tripod exaleiptron in Athens, depicting a satyr exhibiting his phallus and a masturbating komast.162 Masturbating komasts are a feature of early Corinthian and Boiotian iconography, whereas satyrs engaged in this act are not as frequent in these fabrics.163 Moreover, Samon's stance, bent legs, and steatopygic buttocks are reminiscent of komast dancers, which are popular across all Archaic Greek fabrics.164 These figures occasionally display an obscene sexual behavior, especially in Boiotia. They are particularly preoccupied with their buttocks—exhibiting, touching, slapping, or offering them for penetration. Apparently, Samon is a masqueraded variant of the standard figure of the bottom-slapper.165Id. (at 364):

160. Hedreen 1992, p. 128.

161. Samon’s drooping phallus suggests that it is an accessory to his costume, as masturbating figures usually have an erect penis. For the phallus in the comic actor’s costume, see Foley 2000, esp. pp. 277, 281–282, 286, 289–291, 296–302.

162. Athens, National Archaeological Museum 938 (Kilinski 1990, p. 19, pl. 10:3; Isler-Kerényi 2004, p. 29, fig. 12). For ithyphallic proto-satyrs assimilated to grotesque dancers, see Isler-Kerényi 2004, pp. 7–18, 27–33; for performers dressed as silens and for hairy tailless creatures resembling satyrs, see Hedreen 1992, pp. 128–130.

163. Lindblom 2011, pp. 66–67, with previous bibliography.

164. Smith 2010, esp. pp. 150–175 (Boiotia), with previous bibliography.

165. For Boiotian bottom-slappers, see Smith 2010, pp. 165–167.

Bearded komast in the costume of a hairy ithyphallic creature holding his appended phallus or masturbating with his right hand and pushing a stick into his anus with the left; incised inscription: Samon.

Inflation at the Grocery Store

Plautus, Aulularia 373-377 (tr. Wolfgang de Melo):

I went to the market and asked for fish. They told me it's expensive. Lamb: expensive; beef: expensive; veal, tunny, pork: expensive, everything. And they were more expensive for this reason: I didn't have money. I went away from there, angry, since I don't have the money to buy things with.

venio ad macellum, rogito pisces: indicant

caros; agninam caram, caram bubulam,

vitulinam, cetum, porcinam: cara omnia. 375

atque eo fuerunt cariora, aes non erat.

†abeo iratus illinc, quoniam† nihil est qui emam.

377 illinc iratus abeo Guyet

iratus illinc abeo Francken

abeo illim iratus Bothe

abbito...quom Lindsay

<mihi> nil Wagner

Epipompē on an Amulet

Richard Wünsch (1869-1915) first used the terms apopompē (ἀποπομπή) and epipompē (ἐπιπομπή) to describe two different ways of banishing evil. See his "Zur Geisterbannung im Altertum," Festschrift zur Jahrhundertfeier der Universität zu Breslau = Mitteilungen der Schlesischen Gesellschaft für Volkskunde 13/14 (1911) 9-32. Wünsch used apopompē to mean simply driving away evil, epipompē to mean driving away evil onto someone or something else or to some other specific location. A classic example of epipompē can be found in the Gospels (Matthew 8.30-32, Mark 5.11-13, Luke 8.32-33), when Jesus, in performing an exorcism, drove demons into a herd of pigs. All other exorcisms in the Gospels are examples of apopompē.

There is a good example of epipompē on a 4th century A.D. silver lamella from Beyrutus (Beirut), Labanon, now in Paris, Musée du Louvre Bj 88 (Inv. M.N.D. 274), discussed by Roy Kotansky, Greek Magical Amulets. The Inscribed Gold, Silver, Copper, and Bronze Lamellae. Part I: Published Texts of Known Provenance. Text and Commentary (Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag, 1994 = Papyrologica Coloniensia 22/1), pp. 270-300 (number 52 = The Great Angelic Hierarchy). I quote lines 79-119 from Kotansky, p. 281 (underline added):

There is a good example of epipompē on a 4th century A.D. silver lamella from Beyrutus (Beirut), Labanon, now in Paris, Musée du Louvre Bj 88 (Inv. M.N.D. 274), discussed by Roy Kotansky, Greek Magical Amulets. The Inscribed Gold, Silver, Copper, and Bronze Lamellae. Part I: Published Texts of Known Provenance. Text and Commentary (Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag, 1994 = Papyrologica Coloniensia 22/1), pp. 270-300 (number 52 = The Great Angelic Hierarchy). I quote lines 79-119 from Kotansky, p. 281 (underline added):

(79) I adjure you by the Living God in Zoar of the nomadic Zabadeans, the one who thunders and lightnings, EBIEMATHALZERÔ, a new staff (?), by the one who treads, by THESTA, by EIBRADMAS BARBLIOIS EIPSATHAÔTHARIATH PHELCHAPHIAÔN that (?) all male <demons ?> and frightening demons and all bindings-spells (flee) from Alexandra whom Zoê bore, to beneath the founts and the Abyss of Mareôrth,The relevant Greek phrase (lines 93-95 on p. 279, simplified) is ὑποκάτο τῶν πηγῶν καὶ τῆς ἀβύσσου Μαρεώθ.

(95) lest you harm or defile her, or use magic drugs on her,

(97) either by a kiss, or from an embrace, or a greeting;

(100) either with food or drink;

(101) either in bed or intercourse;

(103) either by the evil eye or a piece of clothing;

(105) as she prays (?), either on the street or abroad:

(107) or while river-bathing or a bath.

(109) Holy and mighty and powerful names, protect Alexandra from every demon, male and female,

(114) and from every disturbance of demons of the night and of the day.

(116) Deliver Alexandra whom Zoe bore, now, now; quickly, quickly.

(119) One God and his Christ, help Alexandra.

Thursday, March 23, 2023

The Masses

Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities 5.67.1-2 (tr. Earnest Cary):

[1] For the desires of the unintelligent are not satisfied when they obtain what they demand, but they immediately covet other and greater things, and so on without end; and this is the case particularly with the masses. For the lawless deeds which each one by himself is either ashamed or afraid to commit, being restrained by the more powerful, they are more ready to engage in when they have got together and gained strength for their own inclinations from those who are like minded. [2] And since the desires of the unintelligent mob are insatiable and boundless, it is necessary, he said, to check them at the very outset, while they are weak, instead of trying to destroy them after they have become great and powerful. For all men feel more violent anger when deprived of what has already been granted to them than when disappointed of what they merely hope for.

[1] οὐ γὰρ ἀποπληροῦσθαι τὰς ἐπιθυμίας τῶν ἀφρόνων τυγχανούσας ὧν ἂν δεηθῶσιν, ἀλλ᾽ ἑτέρων εὐθὺς ὀρέγεσθαι μειζόνων καὶ εἰς ἄπειρον προβαίνειν· μάλιστα δὲ τοῦτο πάσχειν τοὺς ὄχλους· ἃ γὰρ καθ᾽ ἑαυτὸν ἕκαστος αἰσχύνεται πράττειν ἢ δέδιεν ὑπὸ τοῦ κρείττονος κατειργόμενος, ταῦτ᾽ ἐν κοινῷ γενομένους ἑτοιμότερον παρανομεῖν προσειληφότας ἰσχὺν ταῖς ἑαυτῶν γνώμαις ἐκ τῶν τὰ ὅμοια βουλομένων. [2] ἀπληρώτους δὲ καὶ ἀορίστους ὑπαρχούσας τὰς τῶν ἀνοήτων ὄχλων ἐπιθυμίας ἀρχομένας ἔφη δεῖν κωλύειν, ἕως εἰσὶν ἀσθενεῖς, οὐχ, ὅταν ἰσχυραὶ καὶ μεγάλαι δύνωνται, καθαιρεῖν. χαλεπωτέραν γὰρ ὀργὴν ἅπαντας ἔχειν τῶν συγχωρηθέντων στερομένους ἢ τῶν ἐλπιζομένων μὴ τυγχάνοντας.

The Passion for Freedom

Greek Anthology 9.294 (Antiphilus of Byzantium; tr. W.R. Paton):

"Xerxes gave thee this purple cloak, Leonidas, reverencing thy valorous deeds." B. "I do not accept it; that is the reward of traitors. Let me be clothed in my shield in death too; no wealthy funeral for me!" A. "But thou art dead. Why dost thou hate the Persians so bitterly even in death?" B. "The passion for freedom dies not."Hugo Stadtmueller in his Teubner edition attributed θαμβήσας to Scaliger. The same conjecture appeared (seemingly independently) in Alph. Hecker, Commentatio Critica de Anthologia Graeca. Pars Prior (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1852), p. 215.

α. "πορφυρέαν τοι τάνδε, Λεωνίδα, ᾤπασε χλαῖναν

Ξέρξης, ταρβήσας ἔργα τεᾶς ἀρετᾶς."

β. "οὐ δέχομαι· προδόταις αὕτα χάρις. ἀσπὶς ἔχοι με

καὶ νέκυν· ὁ πλοῦτος δ' οὐκ ἐμὸν ἐντάφιον."

α. "ἀλλ' ἔθανες· τί τοσόνδε καὶ ἐν νεκύεσσιν ἀπεχθὴς

Πέρσαις;" β. "οὐ θνᾴσκει ζῆλος ἐλευθερίας."

2 ταρβήσας codd.: θαμβήσας Scaliger

The Fashionable Side

Theodore Roosevelt, letter to Albert Cross (June 4, 1912):

Yet is is too true that the large majority of the college presidents, the professors and the like have in this contest sided with the powers of evil. It is the fashionable side today; it is the side taken by the children of this world and probably will bring material rewards to those who take it.

A Work of Reference

Ronald Syme, "Missing Persons III," in his Roman Papers, II (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1979), pp. 530-540 (at 540):

What one looks for in a work of reference is the primary evidence, complete and on clear record. There is no call for long disquisitions or doxology. By contrast, the scholarship of the recent age all too often allows the facts to be choked in verbiage or sunk in bibliography.

Wednesday, March 22, 2023

The Virtues of the True Scholar

Robert Graves, "Diseases of Scholarship, Classically Considered:

A Lecture for Yale University February 13, 1957," in 5 Pens in Hand: Collected Essays, Stories and Poems (Garden City: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1958), pp. 73-90 (at 74):

He puts his duty to factual truth above all other duties.

He allows no religious, or philosophical, or political theory to colour his views.

He is indifferent to fame.

He makes no definite pronouncement on any particular point under discussion before examining and certifying all available evidence.

He never loses touch with specialists in related departments of scholarship, freely exchanging the result of his own researches with them.

He is humble about his knowledge, and willing to consider the views of non-scholars.

He has a close practical knowledge of his subject and keeps himself informed of new discoveries that affect it.

He refuses to exploit his knowledge commercially or socially.

He has a well-developed intuitive power, strengthened by experience.

He allows no superior to interfere with, or influence, his researches.

Nothing and Naught

Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve, "Brief Mention," American Journal of Philology 33.1 (1912) 105-115 (at 111):

As a punishment for my sin in decrying rhyme as a vehicle of translation from the Greek, even in the hands of such a master as Gilbert Murray (A.J.P. XXXI 358-31), I have been haunted by my old enemy while in the Eden of the Anthology, and as I was reading the famous epigram (A.P. X 118), which, if not by Palladas, is in Palladas' vein, the Greek ran itself immediately into a sonnet, not of the best style:I put an interrogation mark at the end of Gildersleeve's first line of Greek, instead of his period, because his translation seemed to demand it. Here is a more literal translation by W.R. Paton:πῶς γενόμην; πόθεν εἰμί; τίνος χάριν ἦλθον; ἀπελθεῖν;

πῶς δύναμαί τι μαθεῖν, μηδὲν ἐπιστάμενος;

Οὐδὲν ἐὼν γενόμην· πάλιν ἔσσομαι ὡς πάρος ἦα·

οὐδὲν καὶ μηδὲν τῶν μερόπων τὸ γένος.

Ἀλλ᾽ ἄγε μοι Βάκχοιο φιλήδονον ἔντυε νᾶμα·

τοῦτο γάρ ἐστι κακῶν φάρμακον ἀντίδοτον.

How came I? is a question claims reply.

Whence am I? will have answer at my hands.

Why came I? is a problem that demands

To be resolved. Just to depart, to die?

How came I? Why, no matter how I try,

Each Argo of adventurous thought but lands

My seeking spirit on a waste of sands.

How can I learn, naught knowing but a why?

Naught was I when I came, and I shall be

Nothing again just as I was before.

Nothing and Naught is all the race of man;

What is there in the world that's left for me,

Save joyance from the Wine God's purple store,

The cure-all holden in the toper's can?

How was I born? Whence am I? Why came I here? To depart again?

How can I learn aught, knowing nothing?

I was nothing and was born; again I shall be as at first.

Nothing and of no worth is the race of men.

But serve me the merry fountain of Bacchus;

for this is the antidote of ills.

Exile

T.R. Glover, Springs of Hellas and Other Essays (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1945), p. 77:

Vergil, Aeneid 8.333-336 (tr. J.W. Mackail):

And the Aeneid is all exiles together. Dido has left Tyre and founded Carthage. Evander, an exquisite figure of simple greatness, tells a similar tale—The footnote is incorrect — the quotation occurs in the 8th book, not the 10th.Me pulsum patria pelagique extrema petentemBut the whole theme of the book is exile—campos ubi Troja fuit—and the promise of a new world won by a man whose life was shattered and his home destroyed—an exile, but a life of victory.

Fortuna omnipotens et ineluctabile fatum

His posuere locis, matrisque egere tremenda

Carmentis nymphae monita et deus auctor Apollo.1

1 Aeneid, x, 333-336.

Vergil, Aeneid 8.333-336 (tr. J.W. Mackail):

Me, cast out from my country and following the utmost limits of the sea, all-powerful Fortune and irreversible doom settled in this region; and my mother the Nymph Carmentis' awful warnings and Apollo's divine counsel drove me hither.

Labels: typographical and other errors

Tuesday, March 21, 2023

Minor Peculiarities of Nature

Pliny the Elder, Natural History 7.80 (tr. Mary Beagon):

But minor peculiarities of nature take many forms and are very common. Drusus' wife, Antonia, for example, did not spit and the poet and one-time consul, Pomponius, never belched.Cf. Solinus 1.74 (p. 18 Mommsen):

sed haec parva naturae insignia in multis varia cognoscuntur; ut in Antonia Drusi numquam exspuisse, in Pomponio consulari poeta non ructasse.

Pomponium poetam consularem virum numquam ructuasse habetur inter exempla: Antoniam Drusi non spuisse percelebre est.

No, By Zingo

Alexander Shewan, Homeric Games at an Ancient St. Andrews: An Epyllium Edited from a Comparatively

Modern Papyrus and Shattered by Means of the Higher Criticism (Edinburgh: J. Thin, 1911),

pp. 29, 31 (lines 110-131):

Why, I pray, dost thou stand in a fright, Oh strong-minded Polemūsa? Come, start the game at once, and make trial and see of what avail is the might of the Phosiloi in the sad mélée of a hot match at kriket. For thou didst once sneer at our prowess, saying that we are the victims of miserable old age, and that we have given over everything to our sons. No, by Zingo, who is nowadays supreme and foremost of gods; we boast ourselves far superior to our sons, who are really a wretched, spiritless, utterly inglorious lot. They care not for manly kriket, but prefer to play goff and bridge with weak girls. They are wild about badmintōn, they ride motor-dicycles, they are effeminate wearers of fine kidskins, slackers who pride themselves on their finger-rings of gold and their two-palm-broad collars of linen, and the beauty wherewith Cytherea of the fair headband hath endowed them. Oh if I were but young, and my muscle as sound, as when I used to pile up big scores time and again! Then would I with a good slog send the leathern ball into the great dark gulf of mouldy Tartarus. But come, no more trifling; give me a ball, and let us see to which of us the Olympian will give the glory.The Greek, pp. 28, 30:

τίπτε μοι ἕστηκας, κρατερόφρων ὦ Πολεμοῦσα, 110

ταρβαλέη; ἀλλ' ἄρχε θοῶς καὶ πειρήτιζε

ὁπποίη Φοσίλων δύναμις πέλετ' ἐν δαῒ λυγρῇ

καυστείρης κρικέτης· πρὶν γὰρ σύ γ' ὀνέιδισας ἡμῖν

ἀλκήν, φᾶσ' ὅτι δὴ δεδμήμεθα γήραϊ λυγρῷ

ἠδ' ὅτι πάνθ' υἱοῖς ἐπιτέτραφθ' ἡμετέροισιν. 115

οὐ μὰ Ζίγγ', ὃς νῦν γε θεῶν ὕπατος καὶ ἄριστος·

ἡμεῖς τοι παίδων μέγ' ἀμείνονες εὐχόμεθ' εἶναι.

οἱ δὲ μάλ' ἀβληχροὶ καὶ ἀκήριοι, ἀκλέες αὔτως·

οὐ κρικέτην φιλέουσ' ἐυήνορα, ἀλλὰ γοφίνδην

συμπαίζειν κούρῃσιν ἀνάλκισιν ἠδὲ γεφύρην, 120

βαδμιντωνομανεῖς, μωτωροδικυκλοκέλητες,

ἁβρεριφοσκυτεσφορανήνορες, αἰνόθρυπτοι.

χρυσέοις δακτυλίοισιν ἀγάλλονται σφετέροισι

καὶ διπαλαίστοισιν περιδειραίοισι λίνοιο,

κάλλεϊ θ' ὅ σφιν ἔδωκεν ἐυστέφανος Κυθέρεια. 125

εἴθ' ὡς ἡβώοιμι βίη δέ μοι ἔμπεδος εἴη

ὡς ὅτ' ἐεικόσια νήεσκον πολλάκι πηγά,

τῷ κε σφαίραν δερματίνην κόψας ἐλάσαιμι

Ταρτάρου ἐς μέγα χάσμα βαθύσκοτον εὐρώεντος.

εἰ δ ̓ ἄγε, μηκέτι νῦν δηθύνῃς, ἀλλὰ πρόες μοι· 130

εἴδομεν ὁπποτέρῳ κεν Ολύμπιος εὖχος ὀρέξῃ.

The Rot Starts at the Top

Antigonus, letter to Zeno, quoted by Diogenes Laertius 7.1.7 (tr. R.D. Hicks):

As is the ruler, such for the most part may it be expected that his subjects will become.Maria Petzold, Quaestiones Paroemiographicae Miscellaneae (Leipzig: Robert Noske, 1904), pp. 22-23 (citing Apostolius):

οἷος γὰρ ἂν ὁ ἡγούμενος ᾖ, τοιούτους εἰκὸς ὡς ἐπὶ τὸ πολὺ γίγνεσθαι καὶ τοὺς ὑποτεταγμένους.

ΙΧ 18 Ἰχθὺς ἐκ τῆς κεφαλῆς ὄζειν ἄρχεται: ἐπὶ τῶν ἐπιστάτας φαύλους ἐχόντων.Samuel Singer, Thesaurus Proverbiorum Medii Aevi. Lexikon der Sprichwörter des romanisch-germanischen Mittelalters, Bd. 3: Erbe - freuen (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1996), p. 269:

Erasm. IV, 2, 97 de hoc proverbio haec disputavit: Piscis a capite primum incipit putere. Dictum in malos principes, quorum contagione reliquum vulgus inficitur. Apparet ab idiotarum vulgo sumptum. — Idem habet Katziules n. 1141: Ἰχθὺς ἀπὸ τῆς κεφαλῆς ὄζει: ἐπὶ δεσπότων παρανομούντων. Vulgarem formam praebet coll. Warn. p. 126 s. v. ψάρι: Τὸ ψάρι ἀπὸ τὸ κέφαλι βρωμᾷ. Cf. Apost. XI 2a vetus Plutarchi proverbium: Ἰχθὺς ἀποκείμενος.

4.1. Der Fisch beginnt am Kopf zu stinkenRelated post: A Fish Begins to Stink From the Head.

145 Mgr. Ἰχθὺς ἐκ τῆς κεφαλῆς ὄζειν ἄρχεται Der Fisch beginnt am Kopf zu stinken APOSTOLIOS 9,18.

146 Mlat. Piscis primum a capite foetet Der Fisch stinkt zuerst am Kopf ERASM., ADAG. CHIL. 4,2,97.

147 It. Il pesce comminda à putir dal capo Übers, wie 145 MERBURY 12.

148. 149 Dt. Der fisch fahet (fängt) am kopff an zu stincken FRANCK 1,36 v. EGENOLFF 299 v.

No Curb or Limit

Ronald Syme, "Bastards in the Roman Aristocracy," in his Roman Papers, II (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1979), pp. 510-517 (at 512):

One of the criteria of a liberal society is the quality of its wit and humour. That was high indeed in the last epoch of the Republic, with notable practitioners, sophisticated as well as coarse. There was no law of libel. Language knew no curb or limit: electoral contests, prosecutions in the courts, altercation or invective in the Senate. In personal abuse of opponents, an orator would bring up all types of crime and depravity.

Monday, March 20, 2023

A Pindaric Calendar

Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve, "Brief Mention," American Journal of Philology 32.4 (1911) 478-487 (at 480-481):

Quoting Latin is out of fashion, quoting Greek quite obsolete, or it might be maintained that no Greek poet of the same bulk of authorship lends himself so readily to quotation as Pindar; and last summer, being off on a holiday and separated from all Greek books except a text of Pindar, I amused myself with constructing a Pindaric Calendar after the fashion of the familiar Shakespeare Calendar, and had no difficulty in finding three hundred and sixty-five quotations—one for each day of the year. To be sure, there are recurrences of thought. There are gods enough for Sundays and Natures enough for week ends, for Phya looms in Pindar as Phye did in the procession of Peisistratos; but for all that there are pat mottoes for every phase of modern life and for all the emergencies of modern politics. Commonplaces? Yes, there are commonplaces, but do we not all live by commonplaces? What gave 'good old Mantuan' his vogue for two centuries except his copy-book sentences? 'Semel insanivimus omnes' has become as familiar a quotation as any in the whole list of household words, though few of us stop at 'semel'. But the famous 'Carmelite', whom Professor MUSTARD has brought back to life for most of us, is as hopelessly 'homely' as Pindar is hopelessly unapproachable in his distinction. What if Pindar does repeat himself in thought? There is wonderful variety in the phrasing, for he is as proud of his ποικιλία as Plato was of his. However, that is an old story, broidered by all the commentators on Pindar. But the other point, the aptness of Pindar's verses as electric signs for our times, might bear one or two illustrations. 'Hands across the sea' is tersely Anglo-Saxon, but οἴκοθεν οἴκαδε is as tersely Greek, and means more for an Anglo-American alliance; and the cry that is ringing in our ears 'See America first' is an echo of οἴκοθεν μάτευε. 'Dollar diplomacy' is one manifestation of ὁ πλοῦτος εὐρυσθενής and τὰν ἔμπρακτον ἄντλει μαχανάν might answer for a treatise on Pragmatism.

The Common Heritage of All Our People

Theodore Roosevelt, letter to George Otto Trevelyan (January 1, 1908):

In Canada, for instance, Wolfe and Montcalm are equally national heroes now, because the English conquered the French and yet live in the country on terms of absolute equality with them, so that of necessity, if they are to have a common national tie, they must have as common heroes for both peoples the heroes of each people. So in a very striking fashion it is with us and the memories of the Civil War. My father's people were all Union men. My mother's brothers fought in the Confederate navy, one being an admiral therein, and the other firing the last gun fired by the Alabama before she sank. When I recently visited Vicksburg in Mississippi, the State of Jefferson Davis, I was greeted with just as much enthusiasm as if it had been Massachusetts or Ohio. I went out to the national park which commemorates the battle and siege and was shown around it by Stephen Lee, the present head of the Confederate veterans' organization, and had as guard of honor both ex-Confederate and ex-Union soldiers. After for many years talking about the fact that the deeds of valor shown by the men in gray and the men in blue are now the common heritage of all our people, those who talked and those who listened have now gradually grown first to believe with their minds, and then to feel with their hearts, the truth of what they have spoken.99th Illinois Infantry Monument at Vicksburg, showing the name of my great-great-grandfather, Robert E. Gilleland, 2nd Lieutenant, 99th Regiment, Illinois Infantry, company I, from Illinois at Vicksburg. Published under Authority of an Act of the Forty-Fifth General Assembly (Chicago: Illinois-Vicksburg Military Park Commission, 1907), p. 274 (2nd panel from the bottom, at the left, 3rd name; click once or twice to enlarge): Some of my ancestors fought on the Confederate side as well.

Siblings

Plautus, Aulularia 127-128 (tr. Paul Nixon):

But just the same, do remember this one thing, brother,—Sophocles, Antigone 905-912 (tr. Richard C. Jebb):

that I am closer to you and you to me than anyone else in the whole world.

verum hoc, frater, unum tamen cogitato,

tibi proximam me mihique esse item te.

Never, if I had been a mother of children,

or if a husband had been rotting after death,

would I have taken that burden upon myself in violation of the citizens' will.

For the sake of what law, you ask, do I say that?

A husband lost, another might have been found,

and if bereft of a child, there could be a second from some other man.

But when father and mother are hidden in Hades,

no brother could ever bloom for me again.

οὐ γάρ ποτ᾽ οὔτ᾽ ἄν, εἰ τέκνων μήτηρ ἔφυν, 905

οὔτ᾽ εἰ πόσις μοι κατθανὼν ἐτήκετο,

βίᾳ πολιτῶν τόνδ᾽ ἂν ᾐρόμην πόνον.

τίνος νόμου δὴ ταῦτα πρὸς χάριν λέγω;

πόσις μὲν ἄν μοι κατθανόντος ἄλλος ἦν,

καὶ παῖς ἀπ᾽ ἄλλου φωτός, εἰ τοῦδ᾽ ἤμπλακον, 910

μητρὸς δ᾽ ἐν Ἅιδου καὶ πατρὸς κεκευθότοιν

οὐκ ἔστ᾽ ἀδελφὸς ὅστις ἂν βλάστοι ποτέ.

God's Pronouns

Hymns on the Celestial Country (Paris: Order of the Golden Age, [1890]), quoted in

The Source of "Jerusalem the Golden" Together With Other Pieces Attributed to Bernard of Cluny. In English Translation by Henry Preble. Introduction, Notes, and Annotated Bibliography by Samuel MacAuley Jackson (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1910), p. 85:

The reader is requested to read Dhey, Dheir, Dhein, for "They, Their, Them," wherever this pronoun is so used to express the Duality in the Deity...Should Dhein be corrected to Dhem?

Sunday, March 19, 2023

Piety

Plautus, Aulularia 23-25 (Lar Familiaris speaking, she = Euclio's daughter Phaedria; tr. Paul Nixon):

She prays to me constantly, with daily gifts of incense, or wine, or something: she gives me garlands.Commentators compare Cato, On Farming 143.2 (among the duties of the vilica; tr. Andrew Dalby):

ea mihi cottidie

aut ture aut vino aut aliqui semper supplicat,

dat mihi coronas.

On the Calends, the Ides, the Nones, and on a feast day, she must place a wreath at the hearth, and on those days she must make offering to the Lar of the Household according to her means.

Kal., Idibus, Nonis, festus dies cum erit, coronam in focum indat, per eosdemque dies lari familiari pro copia supplicet.

Miserable Sinners

Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve, "Brief Mention," American Journal of Philology 31.2 (1910) 234-244 (at 241):

Every now and then Brief Mention adds a paragraph to Dr. Bombaugh's Book of Blunders, but I should dread to put forth a treatise with such a title as Professor POSTGATE'S Flaws in Classical Research (Proceedings of the British Academy, Vol. III). The superscription would remind me too sadly of my own mistakes. True, many scholars follow Maria's programme: 'Cast thy humble slough. Be opposite with a kinsman'. But unfortunately there is always some one to remember the humble slough, and there is always some Sir Toby Belch to hiccup forth a remonstrance. I remember how in years gone by one great apostle of Hellenism made εἱπόμην the middle of εἶπον, and how one of the most savage critics of my day, a veritable canis grammaticus, whose memory comes back to me in the Patou of Rostand's Chantecler, exposed himself time and again to countersnarls. The little notes that I make in Brief Mention are penned in no Malvoliose spirit. I never forgive myself for the slightest slip of the pen, the slightest oversight of the eye, and yet I do derive a certain comfort from the reflection that I am only one of many miserable sinners, and my self-reproach for the inveterate mistakes of my text-books is easier to bear when I recall the persistence of blunders that eluded the vigilance of proofreaders for decennium after decennium like the notorious ἔρχω of Aristophanes, Ranae 111, which was introduced by Brunck in 1783 and retained until the present generation by most of the leading editors.In Aristophanes the correct reading is ἐχρῶ. I don't know who the "great apostle of Hellenism" was.

A Fountain of Light and Learning

H.L. Mencken, "Protestantism in the Republic," Prejudices: Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Series (New York: Library of America, 2010), pp. 239-248 (at 245):

What one mainly notices about these ambassadors of Christ, observing them in the mass, is their vast lack of sound information and sound sense. They constitute, perhaps, the most ignorant class of teachers ever set up to lead a civilized people; they are even more ignorant than the county superintendents of schools. Learning, indeed, is not esteemed in the evangelical denominations, and any literate plowhand, if the Holy Spirit inflames him, is thought to be fit to preach. Is he commonly sent, as a preliminary, to a training camp, to college? But what a college! You will find one in every mountain valley of the land, with its single building in its bare pasture lot, and its faculty of half-idiot pedagogues and broken-down preachers. One man, in such a college, teaches oratory, ancient history, arithmetic and Old Testament exegesis. The aspirant comes in from the barnyard, and goes back in a year or two to the village. His body of knowledge is that of a street-car motorman or a vaudville actor. But he has learned the clichés of his craft, and he has got him a long-tailed coat, and so he has made his escape from the harsh labors of his ancestors, and is set up as a fountain of light and learning.Id.:

How can the teacher teach when his own head is empty?

Saturday, March 18, 2023

Bank Run

Plautus, Truculentus 342 (tr. Wolfgang de Melo):

How pleasant it is to hold on to one's money!

ut rem servare suave est!

American Higher Education

H.L. Mencken, review of Upton Sinclair, The Goose-Step, in Prejudices: Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Series (New York: Library of America, 2010), pp. 257-261 (at 259):

The thing it combats most ardently is not ignorance, but free inquiry; it is devoted to forcing the whole youth of the land into one rigid mold. Its ideal product is a young man who is absolutely correct in all his ideas — a perfect reader for the Literary Digest, the American Magazine, and the editorial page of the New York Times.Id.:

There is scarcely an American university or college in which the scholars who constitute it have any effective control over its general policies and enterprises, or even over the conduct of their own departments. In almost every one there is some unspeakable stock-broker, or bank director, or railway looter who, if the spirit moved him, would be perfectly free to hound a Huxley, a Karl Ludwig or a Jowett from the faculty, and even to prevent him getting a seemly berth elsewhere. It is not only possible; it has been done, and not once, but scores and hundreds of times.

Friday, March 17, 2023

Praesens the Slacker

Pliny, letter to Bruttius Praesens (7.3; tr. P.G. Walsh):

(1) Why do you persist in spending so much time, now in Lucania, and now in Campania? 'The reason is', you reply, 'that I am a Lucanian, and my wife is a Campanian.'A.N. Sherwin-White on calcei:

(2) This is a reasonable excuse for a prolonged absence, but not for an indefinite one. So why don't you return to Rome some time, where your distinction and glory and friendships with both upper and lower classes reside? For how long will you play the monarch? For how long will you enjoy late nights as you wish, and lie in for as long as you like? For how long will your shoes never be worn, your toga remain on holiday, and your day be entirely free?

(3) It is time to revisit our problems, if for no other reason than to avoid letting those pleasures of yours flag through overindulgence. Come and greet us for a short time, to take greater pleasure in being greeted. Experience the crush of this Roman crowd, so as to take full delight in solitude.

(4) But why do I foolishly dissuade one whom I am trying to entice? Perhaps these very exhortations may encourage you to bury yourself more and more in the leisure which I do not wish you to tear yourself away from, but merely to interrupt.

(5) If I were giving you dinner, I would mingle the sweet dishes with tangy and spicy ones, so that when your digestion was dulled and cloyed with the first, it could be sharpened by the second. Likewise I now urge you to season your most sweet manner of life from time to time with a few tart flavours. Farewell.

(1) tantane perseverantia tu modo in Lucania, modo in Campania? 'ipse enim' inquis 'Lucanus, uxor Campana.'

(2) iusta causa longioris absentiae, non perpetuae tamen. quin ergo aliquando in urbem redis? ubi dignitas, honor, amicitiae tam superiores quam minores. quousque regnabis? quousque vigilabis cum voles, dormies quamdiu voles? quousque calcei nusquam, toga feriata, liber totus dies?

(3) tempus est te revisere molestias nostras vel ob hoc solum, ne voluptates istae satietate languescant. saluta paulisper, quo sit tibi iucundius salutari, terere in hac turba, ut te solitudo delectet.

(4) sed quid imprudens, quem evocare conor, retardo? fortasse enim his ipsis admoneris, ut te magis ac magis otio involvas; quod ego non abrumpi, sed intermitti volo.

(5) ut enim, si cenam tibi facerem, dulcibus cibis acres acutosque miscerem, ut obtusus illis et oblitus stomachus his excitaretur, ita nunc hortor, ut iucundissimum genus vitae non nullis interdum quasi acoribus condias. vale.

The senatorial shoe was a high red sandal, distinguished by its lacings (lora, corrigiae), and in the case of patricians by an ivory buckle (lunula). Mommsen, DPR vii.63 ff., discusses it at length.On Bruttius Praesens see Ronald Syme, "Pliny' s Less Successful Friends," in his Roman Papers, II (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1979), pp. 477-495 (at 489-491).

A Neglected Conjecture

Sophocles, Euripides, and Aristophanes are all extensively discussed in John Jackson, Marginalia Scaenica (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1955), but Aeschylus scarcely at all. Unless I'm mistaken, Jackson offers only a single emendation of Aeschylus, at Eumenides 800, on pp. 197-198:

The same conjecture was made independently by Douglas Young, "Some Types of Error in Manuscripts of Aeschylus' Oresteia," Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies 5.2 (1964) 85-99 (at 93, penultimate line on the page). See also Douglas Young, "Readings in Aeschylus' Choephoroe and Eumenides," Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies 12.3 (1971) 303-330 (at 326), where Young recognizes Jackson's priority and notes the omission by Dawe.

ὑμεῖς δ' ἐ<ᾶ>τε τῇδε γῇ βαρὺν κότον.Jackson translates this as "Forgo your heavy anger against this country." This emendation doesn't appear in R.D. Dawe, Repertory of Conjectures on Aeschylus (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1965). It's also ignored by Martin L. West, ed., Aeschyli Tragoediae (Stuttgart: B.G. Teubner, 1998).

The same conjecture was made independently by Douglas Young, "Some Types of Error in Manuscripts of Aeschylus' Oresteia," Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies 5.2 (1964) 85-99 (at 93, penultimate line on the page). See also Douglas Young, "Readings in Aeschylus' Choephoroe and Eumenides," Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies 12.3 (1971) 303-330 (at 326), where Young recognizes Jackson's priority and notes the omission by Dawe.

Usury

Patrick Kurp, "'A Coating of Sensuous Feeling'," Anecdotal Evidence (March 17, 2023):

Screeds, sermons and manifestos are not poetry or even good prose except, rarely, in gifted hands. Neither are crackpot theories (on usury, for example).Ezra Pound (1885-1972), Canto XLV:

With UsuraNotes by Carroll F. Terrell on Canto XLV:

With usura hath no man a house of good stone

each block cut smooth and well fitting

that design might cover their face,

with usura

hath no man a painted paradise on his church wall

harpes et luz

or where virgin receiveth message

and halo projects from incision,

with usura

seeth no man Gonzaga his heirs and his concubines

no picture is made to endure nor to live with

but it is made to sell and sell quickly

with usura, sin against nature,

is thy bread ever more of stale rags

is thy bread dry as paper,

with no mountain wheat, no strong flour

with usura the line grows thick

with usura is no clear demarcation

and no man can find site for his dwelling.

Stonecutter is kept from his stone

weaver is kept from his loom

WITH USURA

wool comes not to market

sheep bringeth no gain with usura

Usura is a murrain, usura

blunteth the needle in the maid's hand

and stoppeth the spinner's cunning. Pietro Lombardo

came not by usura

Duccio came not by usura

nor Pier della Francesca; Zuan Bellin' not by usura

nor was 'La Calunnia' painted.

Came not by usura Angelico; came not Ambrogio Praedis,

Came no church of cut stone signed: Adamo me fecit.

Not by usura St. Trophime

Not by usura Saint Hilaire,

Usura rusteth the chisel

It rusteth the craft and the craftsman

It gnaweth the thread in the loom

None learneth to weave gold in her pattern;

Azure hath a canker by usura; cramoisi is unbroidered

Emerald findeth no Memling

Usura slayeth the child in the womb

It stayeth the young man's courting

It hath brought palsey to bed, lyeth

between the young bride and her bridegroom

CONTRA NATURAM

They have brought whores for Eleusis

Corpses are set to banquet

at behest of usura.

N.B. Usury: A charge for the use of purchasing power, levied without regard to production; often without regard to the possibilities of production. (Hence the failure of the Medici bank.)

Thursday, March 16, 2023

Folly

Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities 5.66.2 (tr. Earnest Cary):

It would be the part of great folly for them, in their desire to gratify the worse part of the citizenry, to disregard the better element, and in confiscating the fortunes of others for the benefit of the most unjust of the citizens, to take them away from those who had justly acquired them.

πολλῆς δ᾽ εἶναι μωρίας ἔργον τῷ χείρονι μέρει τοῦ πολιτεύματος χαρίζεσθαι βουλομένους τοῦ κρείττονος ὑπερορᾶν καὶ τοῖς ἀδικωτάτοις τῶν πολιτῶν τὰς ἀλλοτρίας δημεύοντας οὐσίας τῶν δικαίως αὐτὰς κτησαμένων ἀφαιρεῖσθαι.

One's True Country

Iris Origo, Leopardi: A Study in Solitude (Chappaqua: Helen Marx Books, 1999), pp. 15-16:

Conte Monaldo, the poet’s father, prided himself on his ancestry, on his palace, and on his town—further than that, he considered, a man’s pride should not extend. ‘One’s patriotism is not due to the whole nation,’ he wrote, ‘not even to the state; one’s true country is only that morsel of the earth in which one is born and spends one’s life. That alone should awaken any interest in its citizens.’ In this view, if there was a genuine local patriotism, there was also a keen awareness that it is pleasanter to be a large frog in a small pond. ‘Being very proud’, he himself wrote, ‘of my abilities and personal independence, I neither want nor need a great town. I would always choose a hut, a book, and an onion at the top of a mountain, rather than hold a subordinate position in Rome.’Related posts:

- Think Locally

- Regional Solidarity and Hostility

- Native Soil

- Patria Chica

- Provincialism

- A Blade of Grass

- This Is My Home

- Near and Dear

- Parochialism

- One World

- Local Attachment

- Patriotism

- Insularity

- Xenophobia

- Le Patriotisme de Clocher

- Home Sweet Home

The Future Welfare of the Republic

Theodore Roosevelt, letter to Anna Cabot Mills Lodge (September 10, 1907):

[T]he last few years have convinced me more than ever that it is to the ordinary plain people that we must look for the future welfare of the Republic, and not either to the overeducated parlor doctrinaires, nor to the people of the plutocracy, the people who amass great wealth or who spend it, and who lose their souls alike in one process and the other.Theodore Roosevelt, letter to William Henry Moody (September 21, 1907):

I am continually brought in contact with very wealthy people. They are socially the friends of my family, and if not friends, at least acquaintances of mine, and they were friends of my father's. I think they mean well on the whole, but the more I see of them the more profoundly convinced I am of their entire unfitness to govern the country, and of the lasting damage they do by much of what they are inclined to think are the legitimate big business operations of the day. They are blind to some of the tendencies of the time, as the French noblesse was before the French Revolution; and they possess the same curious mixture of impotency to deal with movements that should be put down and of rancorous stupidity in declining to abandon the kind of reaction and policy which can do nothing but harm. Moreover, usually entirely without meaning it, they are singularly callous to the needs, sufferings, and feelings of the great mass of the people who work with their hands.

Wednesday, March 15, 2023

Typographical Cleanliness

Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve, "Brief Mention," American Journal of Philology 31.1 (1910) 108-117 (at 113):

I am one of those prejudiced persons who distrust any philological work that sins grossly against the rudimentary virtue of typographical cleanliness...

Counting Ballots

Aeschylus, Eumenides 748-751 (tr. Walter Headlam):

Sirs, count up well the cast-out ballots,Against intransitive βαλοῦσά in line 751 see Eduard Fraenkel on Aeschylus, Agamemnon 1172 (ἐν πέδῳ βαλῶ, vol. 3, pp. 534-535, footnotes omitted):

observing honesty in the division of them.

If judgment be absent, there is great harm done,

and the cast of a single vote ere now hath lifted up a house.

πεμπάζετ᾽ ὀρθῶς ἐκβολὰς ψήφων, ξένοι,

τὸ μὴ ἀδικεῖν σέβοντες ἐν διαιρέσει.

γνώμης δ᾽ ἀπούσης πῆμα γίγνεται μέγα, 750

βαλοῦσά τ᾽ οἶκον ψῆφος ὤρθωσεν μία.

751 βαλοῦσά codd.: μολοῦσα Blass: παροῦσά H. Voss: πολλοῖσι Headlam: πεσόντα Blaydes: καμόντα Sommerstein

Visit to Recanati

Iris Origo, Leopardi: A Study in Solitude (Chappaqua: Helen Marx Books, 1999), pp. xiv-xv:

It is sometimes a good plan, however, to go back to one’s starting-point; and while I was re-reading Leopardi’s works, I thought I would also visit his birthplace again. I arrived there on a grey November evening. In the little square before Palazzo Leopardi a piercing wind was raising little eddies of dust and dead leaves, and an old woman—the only human figure in sight—was hobbling up the church steps, with a little straw chair under her arm, her black shawl drawn tightly around her. I followed. In the centre of the nave, beyond the font where Leopardi was baptized, a bier, draped in black velvet, with a great waxen candle at each corner, was prepared for a funeral. The long wooden bench where I knelt still bore the inscription, gentis Leopardae. I came out and wandered up the long, winding street. The shutters of the palazzi were closed; an unusually high proportion of the people I met seemed to be either crippled or infirm; and another blast of biting wind came with renewed vigour up one of the narrow side streets, at the corner where Leopardi’s hat was blown off, and the little boys jeered, as he wrapped his cape over his head.Id. pp. xv-xvi:

I rang the bell of Palazzo Leopardi and was shown into the library; its chill—though it was only November—entered my bones. On the table, in a case, I saw the brown rugs which the poet used to wrap round his shoulders and knees: they seemed thin. Beside his inkstand the petals of the carnation left there by Carducci had shrunk to a pinch of dust. But everything else in the library was unchanged. Still a metal grating enclosed the books forbidden by the Church and among them Leopardi’s own Operette Morali; still the traveller may see the beautiful copperplate hand in which, at ten years old, the poet wrote out his dissertations and his translations of Horace; still he may handle Leopardi’s Virgil, his Tasso, and his great lexicons; and still, across the little square, he may see the window where Leopardi watched Silvia at her loom.

And suddenly it seemed very easy to understand the mixture of love and aversion that Leopardi had felt for his native city. Bitterly as he railed against it, he never ceased to belong there and to feel the tie that tugged him back. He belonged to Recanati as Flaubert did to Rouen, as Joyce to Dublin. This was the town that in his youth he called ‘horrible, detestable, execrated’, a prison, a den, a cave, an inferno, a ‘sepulchre in which the dead are happier than the living’, and ‘the deadest and most ignorant city of the Marches, which is the most ignorant and uncultivated province of Italy’; this the city of whose 7,000 inhabitants he said that they were ‘only remarkable for their endurance in remaining there’, while he himself vowed ‘never to return there permanently until I am dead’. And yet, and yet—hardly had he got to Rome than he wrote to his brother that life in a big city was only bearable if a man could ‘build himself a little city within the great one’. Hardly had he got to Bologna than he was walking upon the hills, ‘seeking for nothing but memories of Recanati’. When he returned there from Rome, it had become ‘la mia povera patria’; when he published his Canti in Florence, he put the name of his birthplace upon the title-page; and when, in the following year, he felt his strength decreasing, he wrote to a friend that if he got any worse he would return to Recanati, ‘since I wish to die at home’. And certainly many of his greatest poems were either written there or directly inspired by his memories of youth and of home, of the night wind stirring in his father’s garden, and the stars shining above his native hills.

A Lost Country

Thucydides 6.92.4 (Alcibiades speaking; tr. Jeremy Mynott):

I do not think of myself now as attacking a city which is still mine so much as reclaiming one which is mine no longer. The true patriot is not the man who holds back from attacking the city he has had unjustly taken from him, but the one who in his passion for it makes every effort to get it back.

οὐδ᾽ ἐπὶ πατρίδα οὖσαν ἔτι ἡγοῦμαι νῦν ἰέναι, πολὺ δὲ μᾶλλον τὴν οὐκ οὖσαν ἀνακτᾶσθαι. καὶ φιλόπολις οὗτος ὀρθῶς, οὐχ ὃς ἂν τὴν ἑαυτοῦ ἀδίκως ἀπολέσας μὴ ἐπίῃ, ἀλλ᾽ ὃς ἂν ἐκ παντὸς τρόπου διὰ τὸ ἐπιθυμεῖν πειραθῇ αὐτὴν ἀναλαβεῖν.

Tuesday, March 14, 2023

Core Vocabulary

Wolfgang de Melo, "Classics in Translation? A Personal Angle (Part I)," Antigone (March, 2023):

[I]n order to understand 90% or more of the words of any text in any language, one needs to know approximately 4,000 words; the most frequent 100 words will give you 50% of any text, because half of any text consists of words like the or forms of be, but thereafter it is a case of diminishing returns, and every further set of 100 words will give you fewer and fewer percent.Id.:

For me, this situation arose when I as a budding Latinist took Italian classes, and later in life when I moved to Belgium, where I was expected to teach in Dutch. With a newborn at home, I didn’t have time to attend a language course until half a year after my arrival; but because German and Dutch are so close, I could easily establish equivalents, figuring out that Dutch d typically corresponds to German t (dag and Tag, both meaning “day”), or that German subordinate clauses end with infinitive + modal verb, while in Dutch the order is typically reversed.[3] After half a year of listening to native speakers in the faculty and a further three-week course at the language centre, I was able to teach in Dutch; such fast progress was only achievable because of my method of establishing equivalents.[4]See also Part II of de Melo's article.

3 Compare English “I am glad that he could come to the meeting”; German “ich bin froh, dass er zum Treffen kommen konnte”; and Dutch “ik ben blij dat hij naar de vergadering kon komen”.

4 Such a contrastive approach also makes us aware of ‘false friends’: German anrufen means “to call someone on the phone”, while Dutch aanroepen means “to call upon the Lord”, a religious meaning which also still exists in German, where it is, however, marginal. If you want to call someone on the phone in Dutch, the verb is bellen (which in German means “to bark”!)

Your Adversary the Devil, as a Roaring Lion?

Roy Kotansky, Greek Magical Amulets. The Inscribed Gold, Silver, Copper, and Bronze Lamellae. Part I: Published Texts of Known Provenance. Text and Commentary (Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag, 1994 = Papyrologica Coloniensia 22/1), p. 68 (Greek simplified here):

Similar demonic-animal attributes, also with the descriptive ὡς, occurs on a special class of bronze pendants, for which see, e.g., C. Bonner, Hesperia 20 (1951), p 354, no. 51: λιμός σε ἔσπιρεν· ἀὴρ ἐθέρισεν· φλέψ σε κατέφαγεν· τί ὡς λύκος μασᾶσε; τί ὡς κορκόδυλλος καταπίννις; τί ὡς λέων βρώχις (= βρύχεις); τί ὡς ταῦρος κερατίζις; τί ὡς δράκων εἱλίσσι; τί ὡς παρᾶος κυμᾶσε; "Hunger sowed you, air harvested you, vein devoured you. Why do you munch like a wolf? Why do you devour like a crocodile? Why do you roar like a lion? Why do you gore like a bull? Why do you coil like a serpent? Why do you lie down like a tame creature?" Perhaps the last τί should be deleted and κυμᾶσε (= κοίμασαι) explained as an imperative: "Lie down like a tame creature!" A parallel text in C. Bonner, Studies in Magical Amulets (Ann Arbor, 1950), p. 217 has ὡς ἀρνίον κοιμοῦ, "go to sleep like a lamb."I wonder about Kotansky's translation of βρώχις (= βρύχεις) as roar. Usually βρύκω (or βρύχω) means bite, gobble, consume (cf. English bruxism = teeth grinding), which is a better parallel here to the munching of the wolf and the devouring of the crocodile.

Preservation of Public Records

Aeschines, Against Ctesiphon 75 (tr. Chris Carey):

It is a good thing, men of Athens, a good thing that we preserve the texts of public documents. This record is unchanging and does not shift its ground to suit political deserters but enables the people, whenever they wish, to recognize individuals who have long been dishonest but change tack and claim to be men of principle.

καλόν, ὦ ἄνδρες Ἀθηναῖοι, καλὸν ἡ τῶν δημοσίων γραμμάτων φυλακή· ἀκίνητον γάρ ἐστι, καὶ οὐ συμμεταπίπτει τοῖς αὐτομολοῦσιν ἐν τῇ πολιτείᾳ, ἀλλ᾽ ἀπέδωκε τῷ δήμῳ, ὁπόταν βούληται, συνιδεῖν τοὺς πάλαι μὲν πονηρούς, ἐκ μεταβολῆς δ᾽ ἀξιοῦντας εἶναι χρηστούς.

Monday, March 13, 2023

Elimination of Beneficial Practices

Aeschines, Against Ctesiphon 3 (tr. Chris Carey):

All the practices that in the past were agreed to be beneficial have nowadays been eliminated.

πάντα τὰ πρότερον ὡμολογημένα καλῶς ἔχειν νυνὶ καταλέλυται.

To Govern Is To Lie

T.R. Glover, Virgil, 2nd ed. (London: Methuen & Co. Ltd., 1912), p. 150, n. 2:

M. Henri Rochefort in the days of the Dreyfus troubles put the same thought in a maxim of wider range:—"Every one knows, and the Ministers best of all, that to govern is to lie (gouverner c'est mentir)." See F.C. Conybeare, The Dreyfus Case, p. 156. It is a brilliant phrase and many people, in ancient times and modern, have believed it—practical politicians and their critics—yes, and thinkers like Euripides and Tolstoi have said it in bitterness of heart. It deserves study.

Autoschediastic Repristinations

Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve, "Brief Mention," American Journal of Philology 26.1 (1905) 111-119 (at 113):

Newer› ‹Older