Sunday, October 31, 2021

The Sword Is Mightier Than the Pen

Cicero, In Defence of Murena 22 (tr. C. Macdonald):

In truth there is no doubt—for I must speak my mind—that success in a military career counts for more than any other. It is this which has won renown for the people of Rome and eternal glory for their city, which has compelled the world to obey our rule. All the activities of this city, all this noble profession of ours, our hard work and recognition here at the Bar lurk in obscurity under the care and protection of prowess in war. The moment that there is a distant rumble of warfare, our arts immediately fall silent.Id. 30:

ac nimirum—dicendum est enim quod sentio—rei militaris virtus praestat ceteris omnibus. haec nomen populo Romano, haec huic urbi aeternam gloriam peperit, haec orbem terrarum parere huic imperio coegit; omnes urbanae res, omnia haec nostra praeclara studia et haec forensis laus et industria latet in tutela ac praesidio bellicae virtutis. simul atque increpuit suspicio tumultus, artes ilico nostrae conticiscunt.

All those activities of yours are dashed from our hands the moment any fresh disturbance sounds the call to arms. In the words of a poet of genius [Ennius] and a very reliable authority, at the declaration of war "there is banished" not only your wordy pretence of wisdom but also that mistress of the world "good sense; force is in control, the orator is rejected" whether he is tiresome and long-winded or whether he is "a good speaker; the rough soldier is courted," but your profession lies abandoned. "They do not go from court to join issue, but rather," he says, "they seek redress with the sword." If this is so, Sulpicius, in my view, let the Forum give way to the camp, peace to war, the pen to the sword, shade to the heat of the sun; in short, concede first place in the State to that profession which has given the State dominion over the world.The quotations are from Ennius' Annals 248–253 Skutsch (tr. Sander M. Goldberg and Gesine Manuwald):

omnia ista nobis studia de manibus excutiuntur, simul atque aliqui motus novus bellicum canere coepit. etenim, ut ait ingeniosus poeta et auctor valde bonus, proeliis promulgatis "pellitur e medio" non solum ista vestra verbosa simulatio prudentiae sed etiam ipsa illa domina rerum, "sapientia; vi geritur res, spernitur orator" non solum odiosus in dicendo ac loquax verum etiam "bonus; horridus miles amatur," vestrum vero studium totum iacet. "non ex iure manum consertum, sed mage ferro" inquit "rem repetunt." quod si ita est, cedat, opinor, Sulpici, forum castris, otium militiae, stilus gladio, umbra soli; sit denique in civitate ea prima res propter quam ipsa est civitas omnium princeps.

good sense is driven from view, by force are affairs managed,

the honest advocate is spurned, the uncouth soldier loved,

not striving with learned speech nor with insulting speech

do they contend among themselves, stirring up hatred;

not to lay claim by law, but rather by the sword—

they press claims and seek mastery—they rush on with force unchecked

pellitur e medio sapientia, vi geritur res;

spernitur orator bonus, horridus miles amatur;

haud doctis dictis certantes, nec maledictis

miscent inter sese inimicitiam agitantes;

non ex iure manum consertum, sed magis ferro—

rem repetunt regnumque petunt—vadunt solida vi.

Saturday, October 30, 2021

The Leaders of the Crowd

W.B. Yeats, "The Leaders of the Crowd," Collected Poems, ed. Richard J. Finneran (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1989), p. 184:

They must to keep their certainty accuse

All that are different of a base intent;

Pull down established honour; hawk for news

Whatever their loose fantasy invent

And murmur it with bated breath, as though

The abounding gutter had been Helicon

Or calumny a song. How can they know

Truth flourishes where the student's lamp has shone,

And there alone, that have no solitude?

So the crowd come they care not what may come.

They have loud music, hope every day renewed

And heartier loves; that lamp is from the tomb.

Slow to Believe

Ovid, Heroides 2.9-10 (tr. Grant Showerman):

We are tardy in believing, when belief brings hurt.

tarde, quae credita laedunt,

credimus.

Friday, October 29, 2021

Meta = In Second Place After, Inferior To

Kim Lyons, "Facebook just revealed its new name: Meta," The Verge (Oct. 28, 2021):

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg announced Thursday at his company's Connect event that its new name will be Meta.A Greek-English Lexicon. [9th Edition] Compiled by H.G. Liddell and R. Scott. Revised and Augmented Throughout by Sir Henry Stuart Jones ... with a Revised Supplement (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996), p. 1109, col. 2, s.v. μετά: Franco Montanari, The Brill Dictionary of Ancient Greek (Leiden: Brill, 1995), p. 1320, col. 3, s.v. μετά: The Backpfeifengesicht of Mark Zuckerberg:

Negatives

Robinson Jeffers, "Foreword" to his Selected Poetry (New York: Randon House, 1938), p. xv:

Another formative principle came to me from a phrase of Nietzsche's: "The poets? The poets lie too much." I was nineteen when the phrase stuck in my mind; a dozen years passed before it worked effectively, and I decided not to tell lies in verse. Not to feign any emotion that I did not feel; not to pretend to believe in optimism or pessimism, or unreversible progress; not to say anything because it was popular, or generally accepted, or fashionable in intellectual circles, unless I myself believed it; and not to believe easily. These negatives limit the field; I am not recommending them but for my own occasions.

Love and Fear

Ovid, Heroides 1.11-12 (tr. Grant Showerman):

When have I not feared dangers graver than the real?Alessandro Barchiesi on line 12:

Love is a thing ever filled with anxious fear.

quando ego non timui graviora pericula veris?

res est solliciti plena timoris amor.

Un concetto volutamente semplice, di buon senso quotidiano, cfr. Cic. Att. 1, 2, 24 non ignoro quam sit amor omnis sollicitus atque anxius. Anche res est ha un sapore idiomatico e colloquiale: molti esempi in Ovidio (cfr. Palmer ad l.; H.-Sz. 444 sg.; A. Traina, Lo stile «drammatico» del filosofo Seneca, Bologna 19874, 86 sg. n. 1). V. anche Ov. met. 7, 719 cuncta timemus amantes!; her. 6, 21 credula res amor est; Pont. 2, 7, 37 res timida est omnis miser; her. 18, 109 omnia sed vereor; quis enim securus amavit?Id., 1.71-72:

But now, what I am to fear I know not—yet none the less I fear all things, distraught,

and wide is the field lies open for my cares.

quid timeam, ignoro—timeo tamen omnia demens,

et patet in curas area lata meas.

A Man Who Liked Certainty

Gerald Brenan (1894-1987), South from Granada (1957; rpt. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980), p. 24:

He was a man who liked certainty. His opinions hardened quickly into dogmas, because by force of repeating them emphatically he made them true. Thus all contradiction was disturbing to him and the smallest suspicion of doubt opened a gap in that phalanx of solid beliefs which he had assembled for his protection and reassurance. He was ready to fight, therefore, to the last ditch on the most insignificant matters, and when defeated would return to the attack a few minutes later from the same positions.

Thursday, October 28, 2021

A Bad Man

Sophocles, Philoctetes 407-409 (Philoctetes referring to Odysseus; tr. Richard C. Jebb):

For well I know that he would lend his tongue to any base pretext, to any villainy, if thereby he could hope to compass some dishonest end.

ἔξοιδα γάρ νιν παντὸς ἂν λόγου κακοῦ

γλώσσῃ θιγόντα καὶ πανουργίας, ἀφ᾽ ἧς

μηδὲν δίκαιον ἐς τέλος μέλλοι ποεῖν.

Long Live Dante!

Aldous Huxley, "Centenaries," On the Margins: Notes & Essays (1923; rpt. London: Chatto and Windus, 1928), pp. 1-11 (at 4-9):

How much better they order these things in Italy! In that country — which one must ever admire more the more one sees of it — they duly celebrate their great men; but celebrate them not with a snuffle, not in black clothes, not with prayer-books in their hands, crape round their hats, and a hatred, in their hearts, of all that has to do with life and vigour. No, no; they make their dead an excuse for quickening life among the living; they get fun out of their centenaries.

Last year the Italians were celebrating the six hundredth anniversary of Dante's death. Now, imagine what this celebration would have been like in England. All the oldest critics and all the young men who aspire to be old would have written long articles in all the literary papers. That would have set the tone. After that some noble lord, or even a Prince of the Blood, would have unveiled a monument designed by Frampton or some other monumental mason of the Academy. Imbecile speeches in words of not more than two syllables would then have been pronounced over the ashes of the world's most intelligent poet. To his intelligence no reference would, of course, be made; but his character, ah! his character would get a glowing press. The most fiery and bitter of men would be held up as an example to all Sunday-school children.

After this display of reverence, we should have had a lovely historical pageant in the rain. A young female dressed in white bunting would have represented Beatrice, and for the Poet himself some actor manager with a profile and a voice would have been found. Guelfs and Ghibellines in fancy dress of the period would go splashing about in the mud, and a great many verses by Louis Napoleon Parker would be declaimed. And at the end we should all go home with colds in our heads and suffering from septic ennui, but with, at the same time, a pleasant feeling of virtuousness, as though we had been at church.

See now what happens in Italy. The principal event in the Dante celebration is an enormous military review. Hundreds of thousands of wiry little brown men parade the streets of Florence. Young officers of a fabulous elegance clank along in superbly tailored riding breeches and glittering top-boots. The whole female population palpitates. It is an excellent beginning. Speeches are then made, as only in Italy they can be made — round, rumbling, sonorous speeches, all about Dante the Italianissimous poet, Dante the irredentist, Dante the prophet of Greater Italy, Dante the scourge of Jugo-Slavs and Serbs. Immense enthusiasm. Never having read a line of his works, we feel that Dante is our personal friend, a brother Fascist.

After that the real fun begins; we have the manifestazioni sportive of the centenary celebrations. Innumerable bicycle races are organized. Fierce young Fascisti with the faces of Roman heroes pay their homage to the Poet by doing a hundred and eighty kilometres to the hour round the Circuit of Milan. High speed Fiats and Ansaldos and Lancias race one another across the Apennines and round the bastions of the Alps. Pigeons are shot, horses gallop, football is played under the broiling sun. Long live Dante!

How infinitely preferable this is to the stuffiness and the snuffle of an English centenary! Poetry, after all, is life, not death. Bicycle races may not have very much to do with Dante — though I can fancy him, his thin face set like metal, whizzing down the spirals of Hell on a pair of twinkling wheels or climbing laboriously the one-in-three gradients of Purgatory Mountain on the back of his trusty Sunbeam. No, they may not have much to do with Dante; but pageants in Anglican cathedral closes, boring articles by old men who would hate and fear him if he were alive, speeches by noble lords over monuments made by Royal Academicians — these, surely, have even less to do with the author of the Inferno.

It is not merely their great dead whom the Italians celebrate in this gloriously living fashion. Even their religious festivals have the same jovial warm-blooded character. This summer, for example, a great feast took place at Loreto to celebrate the arrival of a new image of the Virgin to replace the old one which was burnt some little while ago. The excitement started in Rome, where the image, after being blessed by the Pope, was taken in a motor-car to the station amid cheering crowds who shouted, "Evviva Maria" as the Fiat and its sacred burden rolled past. The arrival of the Virgin in Loreto was the signal for a tremendous outburst of jollification. The usual bicycle races took place; there were football matches and pigeon-shooting competitions and Olympic games. The fun lasted for days. At the end of the festivities two cardinals went up in aeroplanes and blessed the assembled multitudes — an incident of which the Pope is said to have remarked that the blessing, in this case, did indeed come from heaven.

Rare people! If only we Anglo-Saxons could borrow from the Italians some of their realism, their love of life for its own sake, of palpable, solid, immediate things. In this dim land of ours we are accustomed to pay too much respect to fictitious values; we worship invisibilities and in our enjoyment of immediate life we are restrained by imaginary inhibitions. We think too much of the past, of metaphysics, of tradition, of the ideal future, of decorum and good form; too little of life and the glittering noisy moment.

New Interpretations of Old Texts

Hermann Fränkel, Ovid: A Poet between Two Worlds (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1945 = Sather Classical Lectures, 18), p. 1:

As students of classical literature, we cannot expect to have new material wafted onto our desks year in and year out in bountiful quantity; most of the time, we find ourselves handling objects that have been known and used for many centuries. The priceless documents from olden times entrusted to our temporary care remain the same, but each of us will make a fresh effort to comprehend and assess them according to his own lights. There are any number of aspects, all of them equally legitimate, under which a great work of literature may be correctly understood; it is the ephemeral product that allows of one explanation only. On the other hand, any person or generation that is keenly responsive to certain values will inevitably be blind and deaf to certain others, and in the march of literary criticism not every step moves forward. Thus it is only natural that we should frequently be obliged to revise opinions handed down to us.

[....]

However valid a critical judgment may have been in the first place, it will lose some of its cogency with each reiteration, and by the time it has become a truism it has little truth left in it. The reasons for this strange fact seem to be these. Unchallenged perseverance in a belief leads to complacent over-simplification; the complex setting on which the assertion was originally projected gradually fades out, and with its background its justification will be gone; a criticism, in order to be revealing, must stir the mind rather than put it to rest; and we know least about those things we take for granted.

Wednesday, October 27, 2021

Let the Bedstead Creak

Ovid, Amores 3.14.17-26 (tr. Christopher Marlowe):

The bed is for lascivious toyings meete,

There use all tricks, and tread shame under feete,

When you are up, and drest, be sage and grave,

And in the bed hide all the faults you have.

Be not asham'de to strip you being there,

And mingle thighes yours ever mine to beare,

There in your Rosie lips my tongue in-tombe,

Practise a thousand sports when there you come.

Forbeare no wanton words you there would speake,

And with your pastime let the bed-stead creake.

est qui nequitiam locus exigat; omnibus illum

deliciis imple, stet procul inde pudor.

hinc simul exieris, lascivia protinus omnis

absit, et in lecto crimina pone tuo. 20

illic nec tunicam tibi sit posuisse pudori

nec femori impositum sustinuisse femur;

illic purpureis condatur lingua labellis,

inque modos venerem mille figuret amor;

illic nec voces nec verba iuvantia cessent, 25

spondaque lasciva mobilitate tremat.

The Arts and Sciences

Ezra Pound, Literary Essays (New York: New Directions, 1954), p. 225:

The arts and sciences hang together. Any conception which does not see them in their interrelation belittles both. What is good for one is good for the other.

A Ninny

Catullus 17.12-13, 21-22 (tr. F.W. Cornish):

The fellow is a perfect blockhead, and has not as much sense as a little babyHat tip: Eric Thomson.

two years old sleeping in the rocking arms of his father.

[....]

Like this, my booby sees nothing, hears nothing;

what he himself is, whether he is or is not, he does not know so much as this.

insulsissimus est homo, nec sapit pueri instar

bimuli tremula patris dormientis in ulna.

[....]

talis iste meus stupor nil videt, nihil audit,

ipse qui sit, utrum sit an non sit, id quoque nescit.

21 meus codd.: merus Passerat

Tuesday, October 26, 2021

Mark of Culture

Nicolás Gómez Dávila (1913-1994), Escolios a un Texto Implicito, II (Bogotá: Instituto Colombiano de Cultura, 1977), p. 195 (my translation):

A cultured soul is one in which the din of the living does not drown out the music of the dead.

Alma culta es aquella donde el estruendo de los vivos no ahoga la música de los muertos.

The Devil Burning Books

Attachment to One's Native Place

Gerald Brenan (1894-1987), South from Granada (1957; rpt. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980), p. 17:

Like most of the villages of the Sierra Nevada, Yegen was composed of two barrios or quarters, built at a short distance from one another. The barrio de arriba or upper quarter, which was the one in which I lived, began just below the road and ended at the church. Here there was a level space some two or three acres in extent — a break in the endless slope — which was given over to cultivation, and immediately below it the barrio de abajo, or lower quarter, began. The extraordinarily strong feelings of attachment which Spaniards have to their native place showed themselves even in the case of these barrios, for, although there was no difference in their social composition, there was a decided feeling of rivalry between them. People made their friends chiefly in the one in which they lived, and if they had to move house avoided settling in the other. Both in politics and in private quarrels the two barrios tended to take different sides. But since there were no obstacles to intermarriage, the feeling never went very deep and did not of course compare with the gulf which divided one pueblo or village from another.Id., p. 38:

As the months passed by and I came to be better acquainted with the villlage I had chosen for my home, I was surprised to discover what a very self-contained place it was. Even our gentry were not on visiting terms with those of the neighbouring villages, which we scarcely entered except on the occasion of their yearly festivals. Of the two nearest, Válor was disliked because its people were thought to put on airs, while Mecina was laughed at because of its old-fashioned dress and customs. The only ones that we were on good terms with were those that stood at some distance off, especially when they grew different crops and some trade was done with them.Related post: Local Chauvinism.

There was naturally no courting between adjacent villages. It was unthinkable that a man or girl of Yegen should marry anyone from Válor or Mecina. They might, if the opportunity occurred, marry from a remoter town or locality, though even so there were, besides the schoolmistress, only two married women living among us who had been born in other places. One of these was my landlord's wife, Doña Lucía, while the other was the doctor's wife, and they had both met their husbands while these were studying at the University of Granada. What is more, there were only two men in the village besides myself who were not 'sons of the pueblo'. These were the priest and the officially appointed secretary to the municipal council, and both of them came from villages a few miles away. It will thus be easily understood that the sense these villagers had of belonging to a closed community — a Greek polis or a primitive tribe — was very strong. Everyone felt his life bound up with that of the pueblo he had been born into — a pueblo which, through its freely elected municipal officers, governed itself.

Arrival of the Conqueror

Horace, Epodes 16.11-12 (tr. C.E. Bennett):

The savage conqueror shall stand, alas! upon the ashes of our city, and the horseman shall trample it with clattering hoof...Ezekiel 26.11 (KJV):

barbarus heu cineres insistet victor et urbem

eques sonante verberabit ungula...

With the hoofs of his horses shall he tread down all thy streets: he shall slay thy people by the sword, and thy strong garrisons shall go down to the ground.

Monday, October 25, 2021

Exaltavit Humiles

Diphilus, fragment 86 Kassel and Austin (tr. S. Douglas Olson):

O Dionysus, dearest and wisest in the eyes of all those who have any sense, how kind you are! You alone make the humble man proud and persuade the fellow with a haughty expression to laugh, the weak man to take a risk, and the coward to be bold.

ὦ πᾶσι τοῖς φρονοῦσι προσφιλέστατε

Διόνυσε καὶ σοφώταθ᾽, ὡς ἡδύς τις εἶ·

ὃς τὸν ταπεινὸν μέγα φρονεῖν ποιεῖς μόνος,

τὸν τὰς ὀφρῦς αἴροντα συμπείθεις γελᾶν,

τὸν τ᾽ ἀσθενῆ τολμᾶν τι, τὸν δειλὸν θρασύν.

4 συμπείθεις codd.: συμπαθῶς Tucker

"poterat v. 6 sequi εἶναι διδάσκεις vel tale aliquid" Kock

Pasta Names

Oretta Zanini De Vita, Popes, Peasants,

and Shepherds: Recipes and Lore from

Rome and Lazio, tr.

Maureen B. Fant (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013), pp. 4-5:

The same holds for pasta: poverty and imagination lay behind the proliferation of all the many types that changed name from town to town: the stracci of one become fregnacce of another, and the Sabine frascarelli differ little from the strozzapreti of the Ciociaria, the region's southern hinterland. The popular imagination gave whimsical names to the simple paste of water and flour, and only rarely eggs, worked with the hands or with small tools. Thus we have cecamariti (husband blinders) and cordelle (ropes), curuli, fusilli (also called ciufulitti), frigulozzi, pencarelli, manfricoli, and sfusellati, as well as strozzapreti (priest stranglers), the lacchene of the town of Norma and the pizzicotti (pinches) of Bolsena, while the fieno (hay) of Canepina has, accompanied by paglia (straw), been absorbed into the repertory of the pan-Italian grande cucina. All these pastas were served with much the same sauce, plain tomato and basil, though on feast days, pork, lamb, or beef would be added.See also her Encyclopedia of Pasta, tr. Maureen B. Fant (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), p. 117 (s.v. fregnacce):

The term fregnaccia in the dialect of Rome and Lazio means "pack of lies, silliness, trifle" and emphasizes the simplicity of the preparation. It comes from the dialect word fregna, meaning "female genitals." It is curious to note how often popular terminology for pasta, an important dish in the everyday diet, makes reference to sexual organs: along with fregnacce, there are cazzellitti (see entry), pisarei (see entry), and others. All of them are in addition to the many pasta terms that refer to things, animals, or general words of disparagement.

A Kind of Smell Peculiar to the Man

Erasmus, Adages I viii 77 (tr. R.A.B. Mynors, with his note):

77 Aliter catuli longe olent, aliter sues

Dogs and hogs smell very different

In Plautus, in the Epidicus, we find an unattractive but most expressive image: Dogs and hogs smell very different. The words signify that one man is distinguished from another, not by his clothes but by some inborn quality, special and peculiar to each individual, which shines out (to look no further) in his face and the look in his eye and discriminates easily between free man and slave, well-born man and peasant, good man and rascal. This is, as it were, a kind of smell peculiar to the man, by which if you have a keen nose you can tell what he is like. Martial is thinking of it in book six, when he says:A thousand arts she did essayHere belongs the remark of an advocate quoted by Quintilian: 'He does not have even the face of a man of free birth.' The speaker was himself extremely hideous, and counsel for the other party threw it back at him, saying he was quite right; he who did not have a free man's face could not be free-born.

And thought that she had saved the day:

But let her try what tricks she will,

Thais smells of Thais still.

From Plautus Epidicus 579, the title of the play not given till 1523; illustrated from Martial 6.93.11-12 and Quintilian 6.3.32. Otto 361

Aliter catuli longe olent, aliter sues

Apud Plautum legitur in Epidico sordidior quidem metaphora, sed tamen ad rem significandam apta: Aliter catuli longe olent, aliter sues. Quo dicto significatum est non veste dignosci hominem ab homine, verum inesse nativum quiddam genuinum ac proprium in unoquoque, quod in ipso vultu oculisque eluceat, quo liberum a servo, generosum a rustico, probum ab improbo facile discernas. Atque hic est hominis veluti peculiaris quidam odor, quo deprehenditur, si quis modo sit sagaci nare. Huc allusit Martialis libro VI:Cum bene se tutam per fraudes mille putavit,Huc pertinet etiam illud cujusdam apud Fabium: Ne faciem quidem liberi hominis habet. Quod cum a quodam esset dictum deformi specie, retorsit adversarius affirmans recte dictum eum non esse liberum, cui non sit facies liberalis.

Omnia cum ferit, Thaida Thais olet.

The Mythless Motleyness of Modernity

Julian Young, Friedrich Nietzsche: A Philosophical Biography (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), pp. 133-134 (notes omitted):

What is wrong with the mythless 'motleyness' of modernity? In pointing to the specific symptoms of this, Nietzsche develops a 'cultural criticism' which is deeply indebted to Wagner's and which persists with remarkable consistency throughout his career.Most of the quotations come from Nietzsche's The Birth of Tragedy, § 23.

The first symptom is loss of unity. Since the unity of a community, of a 'people', can only exist when individuals are gathered into the 'maternal womb' of a unified myth, there is, in modernity, no community, no homeland. Instead, all we have is a 'wilderness of thought, morals, and action', a 'homeless wandering about'. Modern society has become the atomized world of, in Wagner's phrase, 'absolute egoism', with the only unity being the artificial and oppressive one of the state. As a consequence, communally and so individually, life becomes meaningless.

The second symptom is a 'greedy scramble to grab a place at the table of others', the search for meaning in the supermarket of 'foreign religions and cultures'. One might think here not only of the thriving 'Eastern-guru' business but also of so-called postmodern architecture, the raiding of past and alien styles as an expression of the hollowed-out emptiness of our own culture, which, Nietzsche points out, is not really 'post' modernity at all.

The final symptom is modernity's 'feverish agitation'. The loss of the eternal, mythical perspective on things, the loss of a meaning of life, leads to an 'enormous growth in worldliness', a 'frivolous deification of the present ...of the "here and now"'. This is what modern German sociologists call the Erlebnisgesellschaft — the society driven by the frenzied quest for 'experiences', cheap thrills; for sex, drugs, rock and roll and 'extreme' sports. It is the society described by Wagner as 'bored to death by pleasure'. Without a communal ethos to give aspiration and meaning to one's life, the only way of keeping boredom at bay is the frenzied search for cheap thrills.

Books

Gerald Brenan (1894-1987), South from Granada (1957; rpt. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980), p. 8:

At length my money arrived. I was able to buy a good meal and, what was equally important, a couple of books.Id., p. 9:

I had fetched my suitcase from Granada and so had a few books to read. I spent the last days of waiting sitting under the orange trees with a copy of Spinoza's Ethics and, when that proved too exacting, with Bury's History of Greece. The years of boredom in base-camps and trenches had filled me with a hunger for knowledge, and the first tasks I had set myself when I was settled were to learn something about philosophy and to teach myself Greek. I felt ashamed of being twenty-five and of having read nothing but a few novels and some poetry.

Saturday, October 23, 2021

Time

Diphilus, fragment 84 Kassel and Austin (my translation):

A grey-haired craftsman is time, stranger;See Eduard Fraenkel, Plautine Elements in Plautus, tr. Tomas Drevikovsky and Francis Muecke (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), pp. 40-41.

he likes to remake everyone for the worse.

πολιὸς τεχνίτης ἐστὶν ὁ χρόνος, ὦ ξένε·

χαίρει μεταπλάττων πάντας ἐπὶ τὰ χείρονα.

1 πολιὸς codd.: σκολιὸς Grotius: σκαιὸς Meineke: φαῦλος Hirschig: ποῖος Herwerden: ἄτοπος Haupt: δόλιος Canter: ἄπονος Edmonds

The Approach of an Amateur

Gerald Brenan (1894-1987), Thoughts in a Dry Season (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978), p. viii:

I was never at a university and can claim no special knowledge of anything. All my life I have been a learner rather than a knower, a dabbler in matters that were often beyond my natural range or capacity, so that when I treat of these I can only excuse myself with the hope that in an age of specialists the approach of an amateur may have some interest.

Friday, October 22, 2021

Censorship

Thomas Jefferson, letter to N.G. Dufief (April 19, 1814):

[A]re we to have a censor whose imprimatur shall say what books may be sold, and what we may buy?

A Curse

A curse tablet found in the temple of Mercury, Uley, Gloucestershire in 1978, published by M.W.C. Hassall and R.S.O Tomlin, Britannia 19 (1988) 485–487, with translation (p. 486, sic in original):

Biccus gives Mercury whatever he has lost (that the thief), whether man or male (sic), may not urinate nor defecate nor speak nor sleep nor stay awake nor (have) well-being or health, unless he bring (it) in the temple of Mercury; nor gain consciousness (sic) of (it) unless with my intervention.Latin (p. 487, simplified):

Biccus dat Mercurio quidquid pe(r)d(id)it si vir si mascel ne meiat ne cacet ne loquatur ne dormiat n[e] vigilet nec s[al]utem nec sanitatem ness[i] in templo Mercurii pertulerit ne co(n)scientiam de perferat ness[i] me intercedenteThe curse tablet is now in the British Museum (number 1978,0102.80). See also Sara Paulin, "'Ne meiat, ne cacet, ne loquatur, ne dormiat, ne vigilet.' La sujeción del cuerpo en las tablillas de maldición latinas," in Alicia Schniebs, ed., Discursos del cuerpo en Roma (Buenos Aires: Editorial de la Facultad de Filosofía y Letras Universidad de Buenos Aires, 2011), pp. 185-208.

Thursday, October 21, 2021

Table Manners

Plautus, fragment 55 (tr. Wolfgang de Melo):

I don't blare about politics at table and I don't bellow about the laws.

neque ego ad mensam publicas res clamo nec leges crepo.

The Continuity of Values

Arthur Darby Nock, "The Study of the History of Religion," Essays on Religion and the Ancient World, Vol. I (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1972), pp. 331-340 (at 338):

You cannot read such a book as Westermarck's The Origin and Development of the Moral Ideas without being deeply impressed by the continuity of the virtues in human history. You cannot, of course, read it without becoming aware of the extent to which the details of ethical codes vary in different ages and climes, and are a product of particular forms of social structure and of particular forms of fear and ignorance. You may regard the checks which are so commonly placed on the sexual instinct as explicable from physiological and ritual considerations. But you cannot deny that you find them in some shape almost everywhere. And, what is more important, you find the same generosity, the same hospitality, the same truthfulness, the same respect for legitimate authority held in honour over the world.Id. (at 339):

Furthermore, you will find in the whole story a notable measure of continuity in general. The prophetic innovators of whom we have spoken have nearly all proved to come not to destroy but to fulfil. The movements which sprang from their teaching have nearly all conserved the values which existed in the traditions with which they broke.

It is possible to maintain the unbending supernaturalism of the Catholic Church frankly as a thing revealed to man from without and resting on a divine gift of faith. Here it is all or nothing; one concession would invalidate everything, for it is of the essence of the system that reason is the handmaid of faith, concerned to study and understand what is given to it by faith. This majestic structure is likely to have a very long life as it stands; if I were to have a chance of seeing the world in 2432, by the time machine of H.G. Wells or some similar device, I should confidently expect to find the Latin Mass being said with the same gestures and dogmatic theology being taught according to the principles of St. Thomas Aquinas. The uncompromising nature of Catholicism, its perfect because unconscious correspondence to the needs and aspirations of ordinary humanity, its very otherness are its guarantee of survival. Protestantism is in a very different position. Its basic theory, that it represents a return to the Gospel or to the primitive church, has not stood investigation, and it is from its very nature, from its championship of individual judgment, unable to oppose a fiat of authority to the findings of scholarship. It has to stand before the world absolutely on its own merits, as a frank and deliberate compromise between tradition, or, if you prefer it, revelation and reason; and when you make such a compromise you cannot cry, Stop.Nock's essay was originally published in the Hibbert Journal 31 (1933) 605-615. How inaccurate his prophecy about the Catholic Church has proved to be! The head of that church did his utmost to limit the celebration of the traditional Latin Mass a few months ago in the ironically named Traditionis custodes. The seeds of destruction almost always sprout from within.

A Fierce and Caustic Mockery of Life

Thomas Mann (1875-1955), "Schopenhauer," Essays, tr. H.T. Lowe-Porter (New York: Vintage Books, 1957), pp. 255-302 (at 267-268):

He speaks with a cutting vehemence, in accents of experience and all-embracing knowledge that horrify and bewitch us by their power and veracity. Certain pages display a fierce and caustic mockery of life, uttered as it were with flashing eyes and compressed lips, and in showers of Greek and Latin quotations: a pitiful-pitiless coruscation of statement, citation, and proof of the utter misery of the world. All this is far from being so depressing as one would expect from the pitch of acuity and sinister eloquence it arrives at. Actually it fills the reader with strange, deep satisfaction, whose source is the spiritual rebellion speaking in the words, the human indignation betrayed in what seems like a suppressed quiver of the voice. Everyone feels this satisfaction; everyone realizes that when this great writer and commanding spirit speaks of the suffering of the world, he speaks of yours and mine; all of us feel what amounts almost to triumph at being thus avenged by the heroic Word.

Er spricht davon mit einer schneidenden Vehemenz, mit einem Akzent der Erfahrung, des umfassenden Bescheidwissens, der entsetzt und durch seine gewaltige Wahrheit entzückt. Es ist auf gewissen Seiten ein wilder kaustischer Hohn auf das Leben, funkelnden Blickes und mit verkniffenen Lippen, unter Einstreuung griechischer und lateinischer Zitate; ein erbarmungsvoll-erbarmungsloses Anprangern, Feststellen, Aufrechnen und Begründen des Weltelends,—bei weitem nicht so niederdrückend übrigens, wie man bei soviel Genauigkeit und finsterem Ausdruckstalent erwarten sollte, mit einer seltsam tiefen Genugtuung erfüllend vielmehr kraft des geistigen Protestes, der in einem unterdrückten Beben der Stimme vernehmbaren menschlichen Empörung, die sich darin ausdrückt. Diese Genugtuung empfindet jeder; denn spricht ein richtender Geist und großer Schriftsteller im allgemeinen vom Leiden der Welt, so spricht er auch von deinem und meinem, und bis zum Triumphgefühl fühlen wir alle uns gerächt durch das herrliche Wort.

Wednesday, October 20, 2021

Party Animosities

Thomas Jefferson, letter to Mrs. Church (October, 1792):

Party animosities here have raised a wall of separation between those who differ in political sentiments. They must love misery indeed who would rather, at the sight of an honest man, feel the torment of hatred and aversion than the benign spasms of benevolence and esteem.

The Few and the Many

Plautus, Trinummus 34-35 (tr. Paul Nixon):

We have a crowd here that gives lots more consideration to currying favour with a certain clique than to our general welfare.J.H. Gray ad loc.:

nimioque hic pluris pauciorum gratiam

faciunt pars hominum quam id quod prosint pluribus.

34. nimioque pluris, 'value at a higher price by much,' value far more highly (see on v. 28) the favour of the few. Pauciores )( plures οἱ ὀλίγοι, 'the aristocrats,' 'the optimates.' Cf. the complaints of self-seeking v. 1033 ff.

35. faciunt, plur. after pars hominum which implies a number of persons, a common κατὰ σύνεσιν or ad sensum construction.

quam id quod prosint pluribus, 'than they (value) that wherein they may benefit the many.' This, the reading of A, is supported by Shilleto (quoted by Prof. Mayor on Cic. 2 Phil. 21.30, q.v.). Id is acc. after faciunt, quod is the limiting (adverbial) acc. of neut. pron. so common in Plautus, e.g. Curc. 327 sed quod te misi, nihilo sum certior, 'but I am no wiser about what I sent you for,' lit. 'as to what,' Curc. 456 quid hoc quod ad te uenio? 'but what about the business on which I come to you?' So id and ĭdem frequently. Cf. Ouid. Epist. VI.3.4 hoc tamen ipsum debueram scripto certior esse tuo.

Tuesday, October 19, 2021

Words of a President of the United States of America

Thomas Jefferson, letter to Isaac Weaver, Jr. (June 7, 1807):

Being very sensible of bodily decays from advancing years, I ought not to doubt their effect on the mental faculties. To do so would evince either great self-love or little observation of what passes under our eyes; and I shall be fortunate if I am the first to perceive and to obey this admonition of nature.

Dust

Nicolás Gómez Dávila (1913-1994), Escolios a un Texto Implicito, II (Bogotá: Instituto Colombiano de Cultura, 1977), p. 188 (my translation):

A little dust on a text drives away the average reader.

Un poco de polvo sobre un texto ahuyenta al lector común.

I Wish

Robert Frost (1874-1963), "The Black Cottage," Complete Poems (1948; rpt. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1964), pp. 74-77 (at 77):

For, dear me, why abandon a belief

Merely because it ceases to be true.

Cling to it long enough, and not a doubt

It will turn true again, for so it goes.

Most of the change we think we see in life

Is due to truths being in and out of favor.

As I sit here, and oftentimes, I wish

I could be monarch of a desert land

I could devote and dedicate forever

To the truths we keep coming back and back to.

So desert it would have to be, so walled

By mountain ranges half in summer snow,

No one would covet it or think it worth

The pains of conquering to force change on.

Monday, October 18, 2021

Symbols of Other-World Potations

J.M.C. Toynbee (1897-1985), Death and Burial in the Roman World (1971; rpt. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996), p. 253 (note omitted):

A strange form of gravestone, peculiar, so it seems, to Roman sites in modern Portugal, is the wine barrel lying on its side on a low base, generally with its hoops, and sometimes with rows of wineskins, rendered in relief on its curving surface and a panel reserved for the funerary inscription in a central space between the groups of hoops. The Evora (Ebora) Museum has one, the Conimbriga Museum, near Coimbra, one (without hoops), the Beja (Pax Julia) Museum as many as thirteen and fragments of a number of others; and there is a particularly well preserved example from Algarve in the National Archaeological Museum at Belém on the outskirts of Lisbon. Many more must still exist or have existed. It would appear to be improbable that all the dead persons above whose remains these objects stood had been in the wine trade. The piece at Belém is, in fact, inscribed with the name of a woman who died at the age of twenty-five. These barrels must be symbols of other-world potations or of the wine of new life beyond the grave. Whether they stood directly on the ground or were mounted on pedestals is not known. At any rate they provide a very unusual type of free-standing stelai. (Pl. 81)Id., plate 81:

Below, the gravestone of a young woman, Eppatricia [sic, read Patricia], in the form of a wine-barrel adorned with hoops and wine-skins—a type of monument apparently peculiar to Roman sites in what is now Portugal (p. 253).The inscription is Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum 2.5143:

D(is) M(anibus) s(acrum) / et Patriciae / vixit ann(is) / XXV mens(ibus) / VII dieb(us) VIIII / s(it) t(i)b(i) t(e)r(ra) l(e)b(i)sSee also José d'Encarnação, Inscrições Romanas do Conventus Pacensis: subsídios para o estudo da Romanização (Coimbra: Instituto de Arqueologia da Faculdade de Letras, 1984), pp. 95-96, number 50. Here are more photographs, from d'Encarnação:

Sunday, October 17, 2021

A Holy Thing

Arthur Darby Nock, "The Study of the History of Religion," Essays on

Religion and the Ancient World, Vol. I (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1972), pp. 331-340 (at 333):

A fact is a holy thing, and its life should never be laid down on the altar of a generalization. We have had these generalizations in plenty, and they have worked havoc. The key to all religions and to all mythologies has been sought in various theories—in an emphasis on the worship of ancestors, or on the worship of the heavenly bodies, or on the worship of inanimate and even artificial objects charged with power, or on the kinship of certain social units with animals or plants called totems, or again in the interpretation of all phenomena in terms of mana, the obscure magical force present in various objects, or again in the henotheistic ideas reported as held among quite undeveloped tribes. Each time the key has opened certain doors, but no amount of filing has enabled it to open all doors. Each time the attempt has shown a naïf assumption, characteristic of the ancients and excusable in them, that the universe and the facts of life are ultimately susceptible of a simple explanation. But the universe and the facts of life are stubborn and recalcitrant and the quest for simple explanations is doomed to failure. No big thing is so to be explained. There is no single and simple origin of tragedy or of sacrifice or of funerary ritual. Life does not happen like that. If any domain of the history of man and of his thought seems to us quite straightforward, we may be fairly certain that we are ill-informed about it or view it from a partisan standpoint.

Unattractive Names

Wilfred Thesiger, The Marsh Arabs (1964; rpt. London: Penguin Books, 2007), p. 45:

He was called Jahaish (little donkey). This was not a nickname but his proper name. Many of these tribesmen had wildly improbable names; Jahaish was one of the least odd. I was to meet at various times men or boys called Chilaib (little dog), Bakur (sow) and Khanzir (pig), startling among Moslems, who regarded both dogs and pigs as unclean. Others had such strange names as Jaraizi (little rat), Wawai (jackal), Dhauba (hyena), Kausaj (shark), Afrit (Jinn) and even Barur (dung). In order to avert the evil eye unattractive names like these were often given to boys whose brothers had died in infancy.Related posts:

Small Towns

Julian Young, Friedrich Nietzsche: A Philosophical Biography (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), p. 13 (note omitted, brackets in original):

At least until the beginning of his nomadic mode of life at the end of the 1870s, Nietzsche hated large cities. But small towns where one was protected from the dangers of the wide world by a wall, where one came to know one's neighbours and remained in contact with the countryside, he came to love, particularly Germany's old medieval towns. In 1874, for instance, he wrote to his friend Edwin Rohde that he planned to leave the city of Basel and move to the walled (to this very day) medieval town of Rotenburg-ob-der-Tauber in Franconia since, unlike the cities of modernity, it was still 'altdeutsch' [German in the old-fashioned way] and 'whole'.

A High School Library

Amy Richlin, Slave Theater in the Roman Republic: Plautus and Popular Comedy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), p. 62, n. 93:

My copy of Duckworth's book comes from the North Platte (Nebraska) Senior High School Library, from which it was deaccessioned. This library now no longer contains either a copy of The Nature of Roman Comedy or any book about or by Plautus, and only four books even tangentially about Rome: testimony to the cultural gutting of what are now hinterlands.

Saturday, October 16, 2021

Water

Plato, Euthydemus 304b (tr. W.R.M. Lamb):

Water is cheapest.Plautus, Asinaria 198 (tr. Paul Nixon):

τὸ δὲ ὕδωρ εὐωνότατον.

Daylight, water, sunlight, moonlight, darkness—for these things I have to pay no money.Horace, Satires 1.5.88-89 (tr. H. Rushton Fairclough):

diem aquam solem lunam noctem, haec argento non emo.

Here water, nature's cheapest product, is sold.Seneca, Natural Questions 4.13.3-4 (tr. Thomas H. Corcoran):

venit vilissima rerum

hic aqua.

We have found out how we may compress snow so that it prevails over summer and is protected in a cold place against the season's heat. What have we accomplished by this diligence? Only that we trade in free water. We are sad because we cannot pay for air and sunlight, and because this air comes easily and without cost to the fastidious also and the rich. How unfortunate it is for us that nature has left anything as common property. This water, which nature has allowed to flow for everyone and be available to all, the drinking of which she has made common to life; this water which she has poured forth abundantly and generously for the use of men as well as wild animals, birds, and the laziest creatures; on this water luxury, ingenious against itself, has put a price. So, nothing can please luxury unless it is expensive. Water was the one thing which reduced the wealthy to the level of the mob. In this, the wealthy could not be superior to the poorest man. Someone burdened by riches has thought out how even water might become a luxury.Vitruvius 8.praef.3 (tr. Frank Granger):

invenimus quomodo stiparemus nivem, ut ea aestatem evinceret et contra anni fervorem defenderetur loci frigore. quid hac diligentia consecuti sumus? nempe ut gratuitam mercemur aquam. nobis dolet quod spiritum, quod solem emere non possumus, quod hic aer etiam delicatis divitibusque ex facili nec emptus venit. o quam nobis male est quod quicquam a rerum natura in medio relictum est! hoc quod illa fluere et patere omnibus voluit, cuius haustum vitae publicum fecit, hoc quod tam homini quam feris avibusque et inertissimis animalibus in usum large ac beate profudit, contra se ingeniosa luxuria redegit ad pretium, adeo nihil illi potest placere nisi carum. unum hoc erat quod divites in aequum turbae deduceret, quo non possent antecedere pauperrimum; illi cui divitiae molestae sunt excogitatum est quemadmodum etiam caperet aqua luxuriam.

Water, moreover, by furnishing not only drink but all our infinite necessities, provides its grateful utility as a gracious gift.Lactantius, Divine Institutes 3.26.11 (tr. Mary Francis McDonald):

aqua vero non solum potus sed infinitas usu praebendo necessitates, gratas, quod est gratuita, praestat utilitates.

We do not sell water, nor do we hold forth the sun as a reward.

nos aquam non vendimus nec solem mercede praestamus.

El Jefe

Tacitus, Histories 1.49.8 (tr. Clifford H. Moore):

All would have agreed that he was equal to the imperial office if he had never held it.

omnium consensu capax imperii nisi imperasset.

Friday, October 15, 2021

Mores Maiorum

Paul Zanker, The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus, tr. Alan Shapiro (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1990), p. 156:

Simplicity and self-sufficiency, a strict upbringing and moral code, order and subservience within the family, diligence, bravery, and self-sacrifice: these were the virtues that had continually been evoked in Rome with the slogan "mores maiorum," ever since the process of Hellenization began. Yet in reality this archaic society and its values were receding ever more rapidly. Nevertheless, the belief in the necessity of a moral renewal was firmly rooted. Without a return to the ancestral virtues there could be no internal healing of the body politic.

Such dramatic appeals had surely been heard many times before, and, inevitably, they are vague, short-lived, and out of touch with reality. But despite this, their emotional impact can often be amazingly deep. They are an indispensable element in the eternal longing for a "brave new world."

Peace and Continuity

Wilfred Thesiger, The Marsh Arabs (1964; rpt. London: Penguin Books, 2007), p. 23:

As I came out into the dawn, I saw, far away across a great sheet of water, the silhouette of a distant land, black against the sunrise. For a moment I had a vision of Hufaidh, the legendary island, which no man may look on and keep his senses; then I realized that I was looking at great reedbeds. A slim, black, high-prowed craft lay beached at my feet — the sheikh's war canoe, waiting to take me into the Marshes. Before the first palaces were built at Ur, men had stepped out into the dawn from such a house, launched a canoe like this, and gone hunting here. Woolley had unearthed their dwellings and models of their boats buried deep under the relics of Sumeria, deeper even than evidence of the Flood. Five thousand years of history were here and the pattern was still unchanged.

Memories of that first visit to the Marshes have never left me: firelight on a half-turned face, the crying of geese, duck flighting in to feed, a boy’s voice singing somewhere in the dark, canoes moving in procession down a waterway, the setting sun seen crimson through the smoke of burning reedbeds, narrow waterways that wound still deeper into the Marshes. A naked man in a canoe with a trident in his hand, reed houses built upon water, black, dripping buffaloes that looked as if they had calved from the swamp with the first dry land. Stars reflected in dark water, the croaking of frogs, canoes coming home at evening, peace and continuity, the stillness of a world that never knew an engine. Once again I experienced the longing to share this life, and to be more than a mere spectator.

You Won't Get Away With It

Plautus, Asinaria 489–490 (tr. Paul Nixon):

Do you want to insult another man and not get it back?

I'm as much of a man as you are!

tu contumeliam alteri facias, tibi non dicatur?

tam ego homo sum quam tu.

An Hour a Day

Martin Buber, Tales of the Hasidim, Vol. II: The Later Masters, tr. Olga Marx (New York: Schocken Books, 1948), p. 92:

Rabbi Moshe Leib said:

"A human being who has not a single hour for his own every day is no human being."

A Higher Revelation

Beethoven, quoted in Bettina Brentano, letter to Goethe (May 28, 1810), from O.G. Sonneck, ed., Beethoven: Impressions by His Contemporaries (New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1967), p. 80:

When I open my eyes I must sigh, for what I see is contrary to my religion, and I must despise the world which does not know that music is a higher revelation than all wisdom and philosophy, the wine which inspires one to new generative processes, and I am the Bacchus who presses out this glorious wine for mankind and makes them spiritually drunken. When they are again become sober they have drawn from the sea all that they brought with them, all that they can bring with them to dry land. I have not a single friend; I must live alone. But well I know that God is nearer to me than to other artists; I associate with him without fear; I have always recognized and understood him and have no fear for my music — it can meet no evil fate. Those who understand it must be freed by it from all the miseries which the others drag about with themselves.Did Beethoven really say that, or did Bettina Brentano make it up to impress Goethe?

Wenn ich die Augen aufschlage, so muß ich seufzen; denn, was ich sehe, ist gegen meine Religion, und die Welt muß ich verachten, die nicht ahnt, daß Musik höhere Offenbarung ist als alle Weisheit und Philosophie, sie ist der Wein, der zu neuen Erzeugungen begeistert, und ich bin der Bacchus, der für die Menschen diesen herrlichen Wein keltert und sie geistestrunken macht, wenn sie dann wieder nüchtern sind, dann haben sie allerlei gefischt, was sie mit aufs Trockne bringen. — Keinen Freund hab ich, ich muß mit mir allein leben; ich weiß aber wohl, daß Gott mir näher ist wie den andern in meiner Kunst, ich gehe ohne Furcht mit ihm um, ich hab ihn jedesmal erkannt und verstanden, mir ist auch gar nicht bange um meine Musik, die kann kein bös Schicksal haben, wem sie sich verständlich macht, der muß frei werden von all dem Elend, womit sich die andern schleppen.

Thursday, October 14, 2021

Everybody Needs A Friend

Cicero, On Friendship 23.87 (tr. J.G.F. Powell):

Even if one be of so rude and savage a nature as to shun and hate the society of men, as we have learned was the case with that Timon of Athens, if there ever was such a man, he yet cannot help seeking some one in whose presence he may vomit the venom of his bitterness.

quin etiam si quis asperitate ea est et immanitate naturae, congressus ut hominum fugiat atque oderit, qualem fuisse Athenis Timonem nescio quem accepimus, tamen is pati non possit, ut non anquirat aliquem, apud quem evomat virus acerbitatis suae.

Decrepit

Wallace M. Lindsay, ed., Sexti Pompei Festi De verborum significatu quae supersunt cum Pauli epitome (Leipzig: B.G. Teubner, 1913), p. 62:

Decrepitus est desperatus crepera iam vita, ut crepusculum extremum diei tempus. Sive decrepitus dictus, quia propter senectutem nec movere se, nec ullum facere potest crepitum.Thesaurus Linguae Latinae (TLL), s.v. crepitus, cites this passage under the heading de ventre (4:1170, 79-80), i.e., here crepitum = crepitum ventris. TLL, s.v. decrepitus (5,1:217, 82), derives the adjective from de + crepare. For crepo with the meaning break wind, see TLL 4:1172, 42-48. If we accept Festus' explanation of decrepitus, describing someone who can't break wind because of old age, then I'm not decrepit yet.

Labels: noctes scatologicae

Wednesday, October 13, 2021

Gallows Humor

Antonin J. Obrdlik, "'Gallows Humor'—A Sociological Phenomenon,"

American Journal of Sociology 47.5 (March, 1942) 709-716 (at 712-713):

People who live in absolute uncertainty as to their lives and property find a refuge in inventing, repeating, and spreading through the channels of whispering counterpropaganda, anecdotes and jokes about their oppressors. This is gallows humor at its best because it originates and functions among people who literally face death at any moment. Some of them even dare to collect the jokes as philatelists collect stamps. One young man whom I knew was very proud of having a collection of more than two hundred pieces which he kept safe in a jar interred in the corner of his father's garden. These people simply have to persuade themselves as well as others that their present suffering is only temporary, that it will soon be all over, that once again they will live as they used to live before they were crushed. In a word, they have to strengthen their hope because otherwise they could not bear the strains to which their nerves are exposed. Gallows humor, full of invectives and irony, is their psychological escape, and it is in this sense that I call gallows humor a psychological compensation. Its social influence is enormous. On many an occasion I have observed how one good anecdote changed completely the mood of persons who have heard it—pessimists changed into optimists. Relying on my observations, I may go so far as to say that gallows humor is an unmistakable index of good morale and of the spirit of resistance of the oppressed peoples. Its decline or disappearance reveals either indifference or a breakdown of the will to resist evil. I can remember that those who accepted the New Order as something final and unalterable refused to listen to anecdotes and usually attacked those who repeated them in their presence with sarcastic remarks like this: "You'd better stop making fun of yourself. This is no time to live on jokes." They did not lose their ardent nationalism, but their morale disintegrated—there was no will-power left to resist.

The Triumph of Death

Manilius 4.16 (tr. G.P. Goold):

At birth our death is sealed, and our end is consequent upon our beginning.Propertius 2.28.58 (tr. H.E. Butler):

nascentes morimur, finisque ab origine pendet.

Sooner or later death awaiteth all.These quotations appear at the bottom of The Triumph of Death, by Georg Pencz (1500-1550): The illustration above comes from the Art Institute of Chicago, which recently fired all 122 of its docents.

longius aut propius mors sua quemque manet.

Persistence in Error

Lactantius, Divine Institutes 3.24.10 (tr. Mary Francis McDonald):

I do not know what to say about those who, when once they have gone astray, constantly remain in their foolishness and defend their empty theses with empty prattling, except that sometimes I think that they philosophize for the sake of a joke, or that cleverly and knowingly they take up lies to defend them, so that they might, as it were, exercise or demonstrate their abilities in evil things.

quid dicam de his nescio, qui cum semel aberraverint, constanter in stultitia perseverant et vanis vana defendunt, nisi quod eos interdum puto aut ioci causa philosophari aut prudentes et scios mendacia defendenda suscipere, quasi ut ingenia sua in malis rebus exerceant vel ostendant.

Tuesday, October 12, 2021

Our Task

Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, letter to Hermann Usener (February, 1883; tr. Robert E. Norton), in Usener und Wilamowitz. Ein Briefwechsel 1870-1905 (Leipzig: B.G. Teubner, 1934), p. 28:

Ancient poetry (and naturally law and belief and history) is dead: our task is to enliven it.Related post: Blood for the Ghosts.

Die alte Poesie (und natürlich ebenso Recht und Glaube und Geschichte) ist tot: unsere Aufgabe ist, sie zu beleben.

This Fearful Country

William Shakespeare, The Tempest 5.1.104-106:

All torment, trouble, wonder and amazement

Inhabits here. Some heavenly power guide us

Out of this fearful country!

Ohe, Iam Satis Est!

Horace, Satires 1.5.12-13 (tr. Emily Gowers):

I find it a useful expression these days, when so many things disgust me. To translate Donatus (quoted above by Moreno Soldevila), "Ohe is an interjection signifying surfeit to the point of disgust."

Whoa, that's quite enough!Martial, 4.89.1 (tr. Rosario Moreno Soldevila):

ohe,

iam satis est!

Whoa, that's enough, whoa...Moreno Soldevila ad loc.:

ohe, iam satis est, ohe...

cf. Hor. S. 1.5.12–13. The interjection ohe (Gr. ὠή or ὠῆ) roughly means 'stop it' (OLD s.v. 1a), although it can simply imply impatience or tiresomeness (OLD s.v. 1b): cf. Don. ad Ter. Ph. 377 ohe interiectio est satietatem usque ad fastidium designans. It belongs to oral language; it is, therefore, highly common in comedy: Pl. As. 384; Bac. 1065; Ter. Ph. 418; 1001; cf. Pers. 1.23. It is normally reinforced by the adverb iam (Ter. Ad. 723; 769 [cf. Hau. 879]; Hor. S. 2.5.96), or even by iam satis (Pl. Cas. 248; St. 734). For its prosody, see TLL s.v. 536.36–43 (W.). Both here and in line 9, the first ohe has two long vowels, whereas the second has a short /o/ (cf. 1.31.1, for the different prosody of tibi: tĭbī and tĭbĭ). Martial further uses iam satis est in 7.51.14 et cum 'Iam satis est' dixeris, ille leget (Galán ad loc.); 9.6.4; cf. Pl. As. 329 iam satis est mihi; Hor. S. 1.1.120 iam satis est; Ep. 1.7.16; [Quint.] Decl. 6.7.The sentence is in A. Otto, Die Sprichwörter und sprichwörtlichen Redensarten der Römer (Leipzig: B.G. Teubner, 1890), p. 309 (#1591), but not in Renzo Tosi, Dictionnaire des sentences latines et grecques, tr. Rebecca Lenoir (Grenoble: Jérôme Millon, 2010).

I find it a useful expression these days, when so many things disgust me. To translate Donatus (quoted above by Moreno Soldevila), "Ohe is an interjection signifying surfeit to the point of disgust."

Monday, October 11, 2021

Medieval

Nicolás Gómez Dávila (1913-1994), Escolios a un Texto Implicito, II (Bogotá: Instituto Colombiano de Cultura, 1977), p. 159 (my translation):

To discover the fool, there is no better reagent than the word: medieval. Immediately he sees red.

Para descubrir al tonto no hay mejor reactivo que la palabra: medieval. Inmediatamente ve rojo.

Not a Game

K.J. Dover, "On Writing for the General Reader," The Greeks and their Legacy: Collected Papers, Vol. II (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1988), pp. 304-313 (at 312):

In the past, many a good grammarian has disastrously misinterpreted many a passage of Greek literature because the evidence most relevant to its interpretation was not the kind of evidence he understood, and if Classics were a leisurely game we might be content to say that for the next couple of generations it is someone else's turn. But Classics is not a game; it is an enquiry into what real people actually said and thought and felt and did.

Refutation

Plato, Gorgias 458a (Socrates speaking; tr. Walter Hamilton, rev. Chris Emlyn-Jones):

And what sort of man am I? I am one of those people who are glad to have their own mistakes pointed out and glad to point out the mistakes of others, but who would just as soon have the first experience as the second; in fact I consider being refuted a greater good, inasmuch as it is better to be relieved of a very bad evil oneself than to relieve another.Paul A. Rahe, "Donald Kagan, 1932–2021," New Criterion (October 2021):

ἐγὼ δὲ τίνων εἰμί; τῶν ἡδέως μὲν ἂν ἐλεγχθέντων εἴ τι μὴ ἀληθὲς λέγω, ἡδέως δ᾽ ἂν ἐλεγξάντων εἴ τίς τι μὴ ἀληθὲς λέγοι, οὐκ ἀηδέστερον μεντἂν ἐλεγχθέντων ἢ ἐλεγξάντων· μεῖζον γὰρ αὐτὸ ἀγαθὸν ἡγοῦμαι, ὅσῳπερ μεῖζον ἀγαθόν ἐστιν αὐτὸν ἀπαλλαγῆναι κακοῦ τοῦ μεγίστου ἢ ἄλλον ἀπαλλάξαι.

Working with Don Kagan was a delight. One could argue with the man. He was less attached to his own opinions than to the process of probing and sifting the evidence, and he was open to changing his mind.

Alternative

Cesare Pavese, Diaries (December 20, 1935; my translation):

Either cops or criminals.

O poliziotti o delinquenti.

Sunday, October 10, 2021

Arguments

Plato, Gorgias 457c-e (Socrates speaking; tr. Walter Hamilton, rev. Chris Emlyn-Jones):

I suppose, Gorgias, that like me you have had experience of many arguments, and have observed how difficult the parties find it to define exactly the subject which they have taken in hand and to come away from their discussion mutually enlightened; what usually happens is that, as soon as they disagree and one declares the other to be mistaken or obscure in what he says, they lose their tempers and accuse one another of speaking from motives of personal spite and in an endeavour to score a victory rather than to investigate the question at issue; and sometimes they part on the worst possible terms, after such an exchange of abuse that the bystanders feel annoyed on their own account that they ever thought it worth their while to listen to such people.

οἶμαι, ὦ Γοργία, καὶ σὲ ἔμπειρον εἶναι πολλῶν λόγων καὶ καθεωρακέναι ἐν αὐτοῖς τὸ τοιόνδε, ὅτι οὐ ῥᾳδίως δύνανται περὶ ὧν ἂν ἐπιχειρήσωσιν διαλέγεσθαι διορισάμενοι πρὸς ἀλλήλους καὶ μαθόντες καὶ διδάξαντες ἑαυτούς, οὕτω διαλύεσθαι τὰς συνουσίας, ἀλλ᾽ ἐὰν περί του ἀμφισβητήσωσιν καὶ μὴ φῇ ὁ ἕτερος τὸν ἕτερον ὀρθῶς λέγειν ἢ μὴ σαφῶς, χαλεπαίνουσί τε καὶ κατὰ φθόνον οἴονται τὸν ἑαυτῶν λέγειν, φιλονικοῦντας ἀλλ᾽ οὐ ζητοῦντας τὸ προκείμενον ἐν τῷ λόγῳ· καὶ ἔνιοί γε τελευτῶντες αἴσχιστα ἀπαλλάττονται, λοιδορηθέντες τε καὶ εἰπόντες καὶ ἀκούσαντες περὶ σφῶν αὐτῶν τοιαῦτα οἷα καὶ τοὺς παρόντας ἄχθεσθαι ὑπὲρ σφῶν αὐτῶν, ὅτι τοιούτων ἀνθρώπων ἠξίωσαν ἀκροαταὶ γενέσθαι.

Civil War

Vergil, Eclogues 1.71-72 (tr. H. Musgrave Wilkins):

See to what a pitch of woe civil war has brought our wretched fellow-countrymen!Wendell Clausen ad loc.:

en quo discordia civis

produxit miseros!

discordia: domestic strife, civil war; cf. G. 2.496 'infidos agitans discordia fratres', Cic. Phil. 7.25 'omnia . . . plena odiorum, plena discordiarum, ex quibus oriuntur bella ciuilia'. The collocation 'discordia ciuis' is striking; repeated in A. 12.583 'trepidos inter discordia ciuis' and imitated by Propertius 1.22.5 'cum Romana suos egit discordia ciuis'.

A Quotation About Hebrew

Joseph L. Baron, ed., A Treasury of Jewish Quotations (New York: Aronson, 1985), p. 176 (373.18):

It is worth studying the Hebrew language for ten years in order to read Psalm 104 in the original.The asterisk indicates a non-Jewish author, and DPB stands for Daily Prayer Book (New York: Bloch Publishing Co., 1948). I only have access to Joseph H. Hertz, The Authorised Daily Prayer Book, rev. ed. (New York: Bloch Publishing Company, 1961), where the following appears on p. 582:

*Herder. q Hertz, DPB, 582.

Herder, a pioneer of the appreciation of the Bible as literature, declared, "It is worth while studying the Hebrew language for ten years, in order to read Psalm 104 in the original".No source is given, and I can't find the original quotation. Some German versions of the sentence are floating around on the World Wide Web, but I suspect that they are all translations from the English. One would expect to find the quotation in Herder's Vom Geist der ebräischen Poesie, but it escapes me.

Question

William Shakespeare, The Tempest 5.1.281:

How cam'st thou in this pickle?

Saturday, October 09, 2021

Malleus Maurorum

From a friend:

Greetings from Ourique, close to the site of the battle thereof.Click the photograph once or twice to enlarge it.

I thought I'd photograph this statue of Portugal's first king before it's spray-painted or toppled.

The Wisdom of the Man on the Street

Ernst Jünger (1895–1998), Der Waldgang, § 16, tr. Thomas Friese:

It is rather the case that the ordinary man on the street, whom we meet everywhere, everyday, grasps the situation better than any regime and any theoretician. This ability stems from the surviving traces in him of a knowledge reaching deeper than all the platitudes of the times. It also explains why resolutions can be made at conferences and congresses that are much stupider and more dangerous than the candid opinion of the first random person stepping out of the next streetcar.

Es ist vielmehr so, daß der einfache Mensch, der Mann auf der Straße, dem wir täglich und überall begegnen, die Lage besser erfaßt hat als alle Regierungen und alle Theoretiker. Das beruht darauf, daß in ihm immer noch die Spuren eines Wissens leben, das tiefer reicht als die Gemeinplätze der Zeit. Daher kommt es, daß auf Konferenzen und Kongressen Beschlüsse gefaßt werden, die viel dümmer und gefährlicher sind, als es der Schiedsspruch des Nächsten, Besten wäre, den man aus einer Straßenbahn herauszöge.

Welcome

Seneca, Letters to Lucilius 21.10 (tr. Richard M. Gummere):

Go to his [Epicurus'] Garden and read the motto carved there: "Stranger, here you will do well to tarry; here our highest good is pleasure." The care-taker of that abode, a kindly host, will be ready for you; he will welcome you with barley-meal and serve you water also in abundance, with these words: "Have you not been well entertained?"There is an incorrect citation ("Ep. 79.15") of this motto in Diskin Clay, "The Athenian Garden," in James Warren, ed., The Cambridge Companion to Epicureanism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), pp. 9-28 (at 9).

cum adieris eius hortulos et inscriptum hortulis legerishospes, hic bene manebis, hic summum bonum voluptas est,paratus erit istius domicilii custos hospitalis, humanus, et te polenta excipiet et aquam quoque large ministrabit et dicet: "ecquid bene acceptus es?"

Labels: typographical and other errors

Attraction

Lucretius 2.258 (tr. W.H.D. Rouse):

We proceed whither pleasure leads each.Vergil, Eclogues 2.65 (tr. H. Musgrave Wilkins):

progredimur quo ducit quemque voluptas.

voluptas α-RFC: voluntas Ω

Every man is attracted by his favourite pleasure.Thanks to Alan Crease for drawing my attention to a similar German proverb:

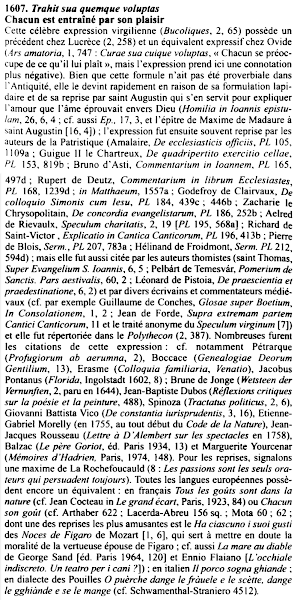

trahit sua quemque voluptas.

Jedem Tierchen sein Pläsierchen.Renzo Tosi, Dictionnaire des sentences latines et grecques, tr. Rebecca Lenoir (Grenoble: Jérôme Millon, 2010), #1607, pp. 1185-1186:

Friday, October 08, 2021

A Waste of Time

Nicolás Gómez Dávila (1913-1994), Escolios a un Texto Implicito, II (Bogotá: Instituto Colombiano de Cultura, 1977), p. 158 (my translation):

To engage in discussion with those who do not share our postulates is nothing more than a foolish way to kill time.

Dialogar con quienes no comparten nuestros postulados no es más que una manera tonta de matar el tiempo.

College Students

Grant Showerman (1870-1935), With the Professor (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1910), pp. 84-85:

Could it be, after all, that his faith had been misplaced—that the value of education was overestimated, and greatly so? He remembered having read the assertion of an English observer to the effect that education was the great national fetich of the United States. He thought of the motley crowd in his own and other institutions with which he was acquainted—of the thousands of aimless young men and women floating along in the current of the college course simply because report had it that education was a good thing; of the thousands more who worked hard first to gain entrance and then to remain, and whose case was hopeless because of natural dullness and deficiency; of the throngs—some stupid and some talented—who were unambitious; of the idlers who came to get culture through being in the college atmosphere, and whose joys and sorrows were almost all inseparably connected with fraternity and sorority life.

Defenceless

Plato, Gorgias 486a-d (Callicles speaking; tr. Walter Hamilton, rev. Chris Emlyn-Jones):

Fragment 186:

Do not be offended, Socrates — I am speaking out of the kindness of my heart to you — aren't you ashamed to be in this plight, which I believe you to share with all those who plunge deeper and deeper into philosophy?The quotations/paraphrases are from Euripides' Antiope, here in the translation of Christopher Collard and Martin Cropp.

As things are now, if anyone were to arrest you or one of your sort and drag you off to prison on a charge of which you were innocent, you would be quite helpless — you can be sure of that; you would be in a daze and gape and have nothing to say, and when you got into court, however unprincipled a rascal the prosecutor might be, you would be condemned to death, if he chose to ask for the death penalty.

But what kind of wisdom can we call it, Socrates, this art that 'takes a man of talent and spoils his gifts', so that he cannot defend himself or another from mortal danger, but lets his enemies rob him of all his goods, and lives to all intents and purposes the life of an outlaw in his own city? A man like that, if you will pardon a rather blunt expression, can be slapped on the face with complete impunity.

Take my advice then, my good friend; 'abandon argument, practise the accomplishments of active life', which will give you the reputation of a prudent man. 'Leave others to split hairs' of what I don't know whether to call folly or nonsense; 'their only outcome is that you will inhabit a barren house.' Take for your models not the men who spend their time on these petty quibbles, but those who have a livelihood and reputation and many other good things.

καίτοι, ὦ φίλε Σώκρατες — καί μοι μηδὲν ἀχθεσθῇς· εὐνοίᾳ γὰρ ἐρῶ τῇ σῇ — οὐκ αἰσχρὸν δοκεῖ σοι εἶναι οὕτως ἔχειν ὡς ἐγὼ σὲ οἶμαι ἔχειν καὶ τοὺς ἄλλους τοὺς πόρρω ἀεὶ φιλοσοφίας ἐλαύνοντας;

νῦν γὰρ εἴ τις σοῦ λαβόμενος ἢ ἄλλου ὁτουοῦν τῶν τοιούτων εἰς τὸ δεσμωτήριον ἀπάγοι, φάσκων ἀδικεῖν μηδὲν ἀδικοῦντα, οἶσθ᾽ ὅτι οὐκ ἂν ἔχοις ὅτι χρήσαιο σαυτῷ, ἀλλ᾽ ἰλιγγιῴης ἂν καὶ χασμῷο οὐκ ἔχων ὅτι εἴποις, καὶ εἰς τὸ δικαστήριον ἀναβάς, κατηγόρου τυχὼν πάνυ φαύλου καὶ μοχθηροῦ, ἀποθάνοις ἄν, εἰ βούλοιτο θανάτου σοι τιμᾶσθαι.

καίτοι πῶς σοφὸν τοῦτό ἐστιν, ὦ Σώκρατες, “ἥτις εὐφυῆ λαβοῦσα τέχνη φῶτα ἔθηκε χείρονα”, μήτε αὐτὸν αὑτῷ δυνάμενον βοηθεῖν μηδ᾽ ἐκσῶσαι ἐκ τῶν μεγίστων κινδύνων μήτε ἑαυτὸν μήτε ἄλλον μηδένα, ὑπὸ δὲ τῶν ἐχθρῶν περισυλᾶσθαι πᾶσαν τὴν οὐσίαν, ἀτεχνῶς δὲ ἄτιμον ζῆν ἐν τῇ πόλει; τὸν δὲ τοιοῦτον, εἴ τι καὶ ἀγροικότερον εἰρῆσθαι, ἔξεστιν ἐπὶ κόρρης τύπτοντα μὴ διδόναι δίκην.

ἀλλ᾽ ὠγαθέ, ἐμοὶ πείθου, “παῦσαι δὲ ἐλέγχων, πραγμάτων δ᾽ εὐμουσίαν ἄσκει”, καὶ ἄσκει ὁπόθεν δόξεις φρονεῖν, “ἄλλοις τὰ κομψὰ ταῦτα ἀφείς”, εἴτε ληρήματα χρὴ φάναι εἶναι εἴτε φλυαρίας, “ἐξ ὧν κενοῖσιν ἐγκατοικήσεις δόμοις”· ζηλῶν οὐκ ἐλέγχοντας ἄνδρας τὰ μικρὰ ταῦτα, ἀλλ᾽ οἷς ἔστιν καὶ βίος καὶ δόξα καὶ ἄλλα πολλὰ ἀγαθά.

Fragment 186:

And how is this wise—an art that takes a naturally robust man and makes him inferior?Fragment 188:

καὶ πῶς σοφὸν τοῦτ᾿ ἐστίν, ἥτις εὐφυᾶ

λαβοῦσα τέχνη φῶτ᾿ ἔθηκε χείρονα;

No, let me persuade you! Cease this idle folly, and practise the fine music of hard work! Make this your song, and you will seem sensible, digging, ploughing the land, watching over flocks, leaving to others these pretty arts of yours which will have you keeping house in a bare home.

ἀλλ᾿ ἐμοὶ πιθοῦ·

παῦσαι ματᾴζων καὶ πόνων εὐμουσίαν

ἄσκει· τοιαῦτ᾿ ἄειδε καὶ δόξεις φρονεῖν,

σκάπτων, ἀρῶν γῆν, ποιμνίοις ἐπιστατῶν,

ἄλλοις τὰ κομψὰ ταῦτ᾿ ἀφεὶς σοφίσματα,

ἐξ ὧν κενοῖσιν ἐγκατοικήσεις δόμοις.

R

Ernst Jünger (1895–1998), Der Waldgang, § 6, tr. Thomas Friese:

On the other hand, through the pressure they themselves create, dictatorships open up a series of weak points that simplify and condense the possibilities for attack. Sticking with our example, even the whole sentence above ["I said no"] would not be necessary. A short "No" would suffice, because everyone whose eye it caught would know exactly what was meant. It would be a sign that the oppression had not entirely succeeded.Nicolas de Chamfort (1741-1794), Maximes et Pensées:

Symbols stand out particularly well on monotoned backgrounds. The gray expanses correlate with a concentration into a minimized space. The signs can manifest as colors, figures, or objects. Where they have an alphabetic character, the script is transformed into pictography. In the process, it gains immediate life, becomes hieroglyphic, and now, rather than explaining, it offers subject matter requiring explanation. One could further abbreviate and, in the place of "No," simply use a single letter — say, an R. This could indicate: Reflect, Reject, React, Rearm, Resist. It could also mean: Rebel.

This would be a first step out of the world of statistical surveillance and control. Yet the question at once arises if the individual is strong enough for such a venture.

Andererseits eröffnen die Diktaturen durch ihren eigenen Druck eine Reihe von Blößen, die den Angriff vereinfachen und abkürzen. So braucht man, um bei unserem Beispiel zu bleiben, nicht einmal den oben erwähnten Satz [»Ich habe Nein gesagt«]. Auch das Wörtchen »Nein« würde ausreichen, und jeder, dessen Augen darauf fielen, würde genau wissen, was es zu bedeuten hat. Das ist ein Zeichen dafür, daß die Unterdrückung nicht völlig gelungen ist.

Gerade auf eintönigen Unterlagen leuchten die Symbole besonders auf. Den grauen Flächen entspricht Verdichtung auf engstem Raum. Die Zeichen können als Farben, Figuren oder Gegenstände auftreten. Wo sie Buchstabencharakter tragen, verwandelt sich die Schrift in Bilderschrift zurück. Damit gewinnt sie unmittelbares Leben, wird hieroglyphisch und bietet nun, statt zu erklären, Stoff für Erklärungen. Man könnte noch weiter abkürzen und statt des »Nein« einen einzigen Buchstaben setzen — nehmen wir an, das W. Das könnte dann etwa heißen: Wir, Wachsam, Waffen, Wölfe, Widerstand. Es könnte auch heißen: Waldgänger.

Das wäre ein erster Schritt aus der statistisch überwachten und beherrschten Welt. Und sogleich erhebt sich die Frage, ob denn der Einzelne auch stark genug zu solchem Wagnis ist.

Almost all men are slaves, for the reason the Spartans gave to explain the servitude of the Persians, the inability to pronounce the syllable "No." Knowing how to pronounce this word and knowing how to live by oneself are the only two ways to preserve one's freedom and individuality.

Presque tous les hommes sont esclaves par la raison que les Spartiates donnaient de la servitude des Perses, faute de savoir prononcer la syllabe non. Savoir prononcer ce mot et savoir vivre seul sont les deux seuls moyens de conserver sa liberté et son caractère.

Thursday, October 07, 2021

Too Hard for the American Brain

John Jay Chapman (1862-1933), "A New Menace to Education: The Growing Contempt for Culture and the Classics in American Universities," Meredith College, Quarterly Bulletin 1919-1920: Special Education Number, pp. 1-6 (at 1, footnote omitted):