Wednesday, August 31, 2022

Wolf Pack

Jan Bremmer, "The Suodales of Poplios Valesios," Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 47 (1982) 133-147 (at 141):

The members of the fían, the fénnid, were regularly connected with wolfs and wild dogs, and this fits in well with the fact that among the Indo-Europeans strangers and boys who had to live away from civilised society were often called dog or wolf, or even dressed as such; this custom is found among the Irish, Germans, Greeks, Lithuanians, Hittites and Indo-Iranians (below). Moreover, among these peoples many tribal and personal names are composed with the element 'wolf' (Lycii, Lycurgus etc.), and it is hard to attribute this only to the bearers' having been criminals; it rather points to the time when they lived away from society during their initiation, or when they were performing heroic feats to prove their manhood.35)Related posts:

35) Wolfs and outlaws: L. Gernet, Anthropologie de la Grèce antique (Paris 1968), 154-171 ("Dolon le loup"); E. Richardson, The Wolf in the West, J.Walters Art Gallery 36 (1971), 91-102; M.R. Gerstein, Germanic Warg: the Outlaw as Werwolf, in G.J.Larson (ed.), Myth in Indo-European Antiquity (Berkeley etc. 1974), 131-156; M. Jacoby, Wargus, vargr 'Verbrecher' Wolf (Uppsala 1974); R.Schmidt-Wiegand, Wargus, in H. Jankuhn e.a. (eds.), Zum Grabfrevel in vor- und frühgeschichtlicher Zeit, Abh. Ak. Göttingen, Philol.-hist. Klasse III 113 (Göttingen 1978), 188-196; E. Campanile, Meaning and Prehistory of Old Irish Cú Glas, J. Indo-European Studies 7 (1979), 237-247; F.Graf, Nordionische Kulte (Rome 1982), the chapter on Apollo Lykeios. Personal names: E. Campanile, Ricerche di cultura poetica indoeuropea (Pisa 1977), 80-82. Tribal names: M. Eliade, Zalmoxis, The Vanishing God (Chicago/London 1972), 1-3; O.N. Trubacev, in R. Schmitt (ed.), Etymologie (Darmstadt 1977), 262-265; H. Kothe, Nationis nomen, non gentis, Philologus 123 (1979, 242-287), 274-282, 286f.

The role of the dog has been much less researched, but we may mention the Longobard Cynocephali who have been studied in a brilliant article by O. Höfler, Cangrande von Verona und das Hundesymbol der Longobarden, in Brauch und Sinnbild. Festschrift E. Fehrle (Karlsruhe 1940), 101-137; H. Birkhan, in Festgabe für Otto Höfler (Wien 1976), 36f. (on the Lithuanian 'Jungmannschaft' fighting with dog's heads); L. Kretzenbacher, Kynokephale Dämonen südosteuropäischer Volksdichtung (München 1968); Kothe, op. cit., 251, 259 (dogs and tribal names); C. Lecouteux, Zs. f. deutsches Alt. 110 (1981), 213-217.

The Greek Miracle

Ernest Renan, Recollections of My Youth, tr. C.B. Pitman (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1883), pp. 50-52:

The impression which Athens made upon me was the strongest which I have ever felt. There is one and only one place in which perfection exists, and that is Athens, which outdid anything I had ever imagined. I had before my eyes the ideal of beauty crystallised in the marble of Pentelicus. I had hitherto thought that perfection was not to be found in this world; one thing alone seemed to come anywhere near to perfection. For some time past I had ceased to believe in miracles strictly so called, though the singular destiny of the Jewish people, leading up to Jesus and Christianity, appeared to me to stand alone. And now suddenly there arose by the side of the Jewish miracle the Greek miracle, a thing which has only existed once, which had never been seen before, which will never be seen again, but the effect of which will last for ever, an eternal type of beauty, without a single blemish, local or national. I of course knew before I went there that Greece had created science, art, and philosophy, but the means of measurement were wanting. The sight of the Acropolis was like a revelation of the Divine, such as that which I experienced when, gazing down upon the valley of the Jordan from the heights of Casyoun, I first felt the living reality of the Gospel. The whole world then appeared to me barbarian. The East repelled me by its pomp, its ostentation, and its impostures. The Romans were merely rough soldiers; the majesty of the noblest Roman of them all, of an Augustus and a Trajan, was but attitudinizing compared to the ease and simple nobility of these proud and peaceful citizens. Celts, Germans, and Slavs appeared as conscientious but scarcely civilised Scythians. Our own Middle Ages seemed to me devoid of elegance and style, disfigured by misplaced pride and pedantry, Charlemagne was nothing more than an awkward German stableman; our chevaliers louts at whom Themistocles and Alcibiades would have laughed. But here you had a whole people of aristocrats, a general public composed entirely of connoisseurs, a democracy which was capable of distinguishing shades of art so delicate that even our most refined judges can scarcely appreciate them. Here you had a public capable of understanding in what consisted the beauty of the Propylon and the superiority of the sculptures of the Parthenon. This revelation of true and simple grandeur went to my very soul. All that I had hitherto seen seemed to me the awkward effort of a Jesuitical art, a rococo mixture of silly pomp, charlatanism, and caricature. These sentiments were stronger as I stood on the Acropolis than anywhere else.

A Gasbag

Cicero, On the Orator 2.18.75 (tr. E.W. Sutton and H. Rackham):

Nor do I need any Greek professor to chant at me a series of hackneyed axioms, when he himself never had a glimpse of a law-court or judicial proceeding, as the tale goes of Phormio the well-known Peripatetic; for when Hannibal, banished from Carthage, had come in exile to Antiochus at Ephesus and, inasmuch as his name was highly honoured all the world over, had been invited by his hosts to hear the philosopher in question, if he so pleased, and he had intimated his willingness to do so, that wordy individual is said to have held forth for several hours upon the functions of a commander-in-chief and military matters in general. Then, when the other listeners, vastly delighted, asked Hannibal for his opinion of the eminent teacher, the Carthaginian is reported to have thereupon replied, in no very good Greek, but at any rate candidly, that time and again he had seen many old madmen but never one madder than Phormio.

nec mihi opus est Graeco aliquo doctore, qui mihi pervulgata praecepta decantet, cum ipse nunquam forum, nunquam ullum iudicium aspexerit: ut Peripateticus ille dicitur Phormio, cum Hannibal Carthagine expulsus Ephesum ad Antiochum venisset exsul, proque eo, quod eius nomen erat magna apud omnes gloria, invitatus esset ab hospitibus suis, ut eum, quem dixi, si vellet, audiret; cumque is se non nolle dixisset, locutus esse dicitur homo copiosus aliquot horas de imperatoris officio et de re militari. tum, cum ceteri, qui illum audierant, vehementer essent delectati, quaerebant ab Hannibale, quidnam ipse de illo philosopho iudicaret. his Poenus non optime Graece, sed tamen libere respondisse fertur, multos se deliros senes saepe vidisse, sed qui magis, quam Phormio deliraret, vidisse neminem.

Religious Tradition

Cicero, On the Laws 2.8.19 (tr. Niall Rudd):

No one shall have gods of his own, whether new or foreign, unless they have been officially brought in. In private they shall worship those gods whose worship has been handed down in its proper form by their forefathers.The Latin text with an image of the critical apparatus from J.G.F. Powell, ed., M. Tullius Ciceronis De Re Publica, De Legibus, Cato Maior De Senectute, Laelius De Amicitia (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), p. 203:

In the cities they shall have shrines; in the countryside they shall have groves and abodes for their tutelary gods.

They shall preserve the rituals of their family and fathers.

Separatim nemo habessit deos, neve novos neve advenas, nisi publice adscitos. Privatim colunto quos rite a patribus <cultos acceperint.Johan Nicolai Madvig, Disputatio de emendandis Ciceronis libris de legibus (Copenhagen: Typis Directoris Iani Hostrup Schultzii, 1836), p. 7 = his Opuscula Academica (Copenhagen: Sumptibus Librariae Gyldendalianae, 1887), pp. 508-509:

In urbibus> delubra habento, lucos in agris habento et Larum sedes.

Ritus familiae patrumque servanto.

Sed sequitur: Constructa a patribus delubra in urbibus habento. 2) Ridiculam legem! Qui enim praecipi id potest, quod totum non in ipsius, cui praecipitur, potestate positum sit, sed in patrum facto? Si enim nulla delubra patres construxerunt, nulla posteri habere ab iis constructa possunt; ipsi possunt et exstruere et habere. Atque hoc praecipere volebat Cicero; nam ex interpretatione legis apparet, respici contrariam Persarum sententiam, qui nulla esse templa deorum volebant. (Itaque Patrum delubra, quod ibi scribitur, in eadem perversitate est, a Wyttenbachio ob aliam causam correctum, quod patrum delubra pro iis, quae patres exstruxissent, non diceretur. Poterat addere, necessarium esse ipsi patres.) Atque haec tam perversa sententia in ceteris codicibus est omnibus; in iis duobus, quos dixi, totus locus sic scriptus est: privatim colunto quos rite a patribus delubra habento. Jam aperta res est. Quum in eo codice, ex quo nostri descripti sunt, vocabulum unum aut etiam plura excidissent, emendator sententiam superiorem in colunto finivit, quos rite mutavit in constructa, salva grammatica et specie sententiae, ipsa sententia pessumdata. Ea emendatio in solos illos duos codices non pervasit, ex quibus apparet, Ciceronem hac forma sententiam legis concepisse: Separatim nemo habessit deos neve novos neve advenas, nisi publice adscitos. Privatim colunto, quos rite a patribus [cultos acceperint] 3). Delubra habento.

2) Voces in urbibus nullus habet codex, nec iis opus est, quamquam in legis explicatione adduntur, quod templa fere in urbibus erant. Generaliter dicitur: delubra habento; deinde speciatim additur de lucis in agris ceterisque, ut ne contrarii quidem causa (oppositionem appellant) necessarium additamentum sit.

3) Hoc est, in quibus colendis ipsi patres legi paruerint, ut est in explicatione legis. Seiungitur a separato cultu privatus familiarum cultus a maioribus acceptus. In supplemento nihil praeter sententiam praesto.

Tuesday, August 30, 2022

Change

Armand D'Angour, The Greeks and the New: Novelty in Ancient Greek Imagination and Experience (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), pp. 37-38:

From this background Aristotle proceeds to reflect briefly on the question of political innovation in general, concluding that a distinction should be drawn between tekhnē, the sphere of specialist disciplines, and nomos, that of law and politics. Regarding laws, he says,a case may be made for the view that change (kīnein) is the better policy. Certainly in other branches of knowledge change has proved beneficial. We may cite in evidence the changes from traditional practice which have been made in medicine, in physical training, and generally in all the arts and forms of human skill; and since politics is to be counted as an art or form of skill, it can be argued logically that the same must also be true of politics.6This analysis recalls the words attributed by Thucydides to the Corinthian envoy to Sparta in 431:In politics as in technology (tekhnē), the new (epigignomena) must always prevail over the old. The established traditions may be best in a settled society, but when there is much change demanding a response there must be much innovative thinking also.7However, Aristotle ends his discussion by rejecting the parallel between law and tekhnē, and poses a series of questions about pertinent differences in the implementation of political innovation:We must also notice that the analogy drawn from the arts is false. To change the practice of an art is not the same as to change the operation of a law. It is from habit, and only from habit, that law derives the validity which secures obedience. But habit can be created only by the passage of time; and a readiness to change from existing to new and different laws will accordingly tend to weaken the general power of law. Further questions may also be raised. Even if we admit that it is allowable to make a change, does this hold true, or not, of all laws and in all constitutions? And again, should change be attempted by any person whatsoever, or only by certain persons? It makes a great difference which of these different alternatives is adopted . . . We may therefore dismiss this question for the present. It belongs to a different occasion.86 Ibid. [Arist. Pol.] 1268b33–8.

7 Thuc. 1.71.3. See further Chapter 9, p. 221.

8 Arist. Pol. 1269a19–28.

The Vix Krater

Bijan Omrani, Caesar's Footprints. A Cultural Excursion to Ancient France: Journeys Through Roman Gaul (New York: Pegasus Books, 2017), p. 16:

Paul MacKendrick, Roman France (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1972), p. 14:

By examining some of the archaeological finds of this age, it is possible to imagine how Gallic tribesmen might have reacted when they first set eyes on the luxury imports of the Greeks. For a vignette, let us set the date at 520 BC, at a Gallic settlement on the flat-topped hill of Mont Lassois by the upper reaches of the Seine in northeastern Burgundy. A number of boxes have been brought up the hill into the camp of wooden huts and palisades. The boxes contain together just one item, but being a heavy import, it is flat-packed for self-assembly. Fortunately, there are instructions — scratched-on Greek letters, indicating which part should be joined to which. As the tribesmen labour to join the pieces together — handles, stand, cover — the item takes shape. It is not easy work. The item is metal, refulgent hammered bronze, weighing over 200 kilograms, with individual components of as much as 60 kilograms. When finished, it stands at least as high as the tribesmen, at 1.6 metres (5 foot 4 inches). This is no simple bookshelf or bedstead, but a colossal 1,200-litre wine cauldron, or krater. It is the largest such item known from the ancient world, and is intricately and skilfully worked. Gorgons, menacing, with snakes in their hair and tongues sticking out through grimacing smiles, glare from the handles, as do rampant lions, their muscles taut and claws digging into the metalwork, while their tails echo in their curve the elegant whorls and scrolls chased into the rim and the volutes of the handles. In a band below the rim that runs the whole circumference of the krater, Greek soldiers, hoplites, march in an endless parade. They are naked save for great fan-crested helmets (whose plumage reaches down to their waist), greaves and round, dish-like shields strapped to their left arms. Some ride on chariots whose horses, ambling and stately, peer inquisitively at the new owners of the krater.For Yanks like me, 1200 litres = 317 gallons.

Paul MacKendrick, Roman France (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1972), p. 14:

Marseille may have been the port of transshipment for the most impressive piece of Greek metalwork ever found in France, or anywhere else for that matter, the bronze crater (punchbowl) of Vix (Fig. 1.6). It was found in January 1953, the most striking of fifty-three objects in the wood-lined chamber of a tumulus (burial mound) 138 feet across, which was being excavated near Châtillon-sur-Seine. It stands over 5 feet tall, and weighs 436 pounds. Snake-haired Gorgons decorate the handles; between the handles runs a frieze of chariots, charioteers, and warriors wearing the armor fashionable in the Ripe Archaic period, the late sixth century B.C. The body of the vase was made in one piece, without soldering, beaten when cold, and polished. Each of the men and horses in the frieze differs slightly from every other, so that it is clear this is the loving hand-work of a craftsman of genius, and not made from molds. The bowl has a cover, weighing 30 pounds; in its center the statuette of a goddess, six inches high, wearing a belted, pleated robe and a Mona Lisa smile.Some photographs from René Joffroy, "La tombe de Vix (Côte-d'Or)," Monuments et mémoires de la Fondation Eugène Piot 48.1 (1954) 1-68 (click on each photograph once or twice to enlarge):

Monday, August 29, 2022

Hardly Treason

Page Smith, John Adams, Vol. II: 1784-1826 (Garden City: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1962), p. 1033, with note on p. 1152:

He addressed fourteen questions to his Cabinet officers in regard to Fries' rebellion and the legal questions involved in the charge of treason. The Secretaries were unanimous in recommending that the sentence of death for treason be carried out on the three accused and Charles Lee concurred; but the more Adams thought about it the more convinced he was that it would be a disservice to the nation to extend the definition of treason so far. Fries' "rebellion" was to him no more "than a riot, highhanded, aggravated, daring, and dangerous indeed," but hardly treason. "Is there not great danger in establishing such a construction of treason as may be applied to every sudden, ignorant, inconsiderable heat among a part of the people wrought up by political dispute?"12

12. AA/TBA, October 12, 1800, APm.

Stage Fright

Cicero, In Defense of Cluentius 18.51 (tr. H. Grose Hodge):

And then I rose to reply, and Heaven knows how anxious I was, how uneasy, how apprehensive! Personally, I am always very nervous when I begin to speak. Every time I make a speech I feel I am submitting to judgement, not only my ability but even my character and honour, and am afraid of seeming either to promise more than I can perform, which suggests shamelessness, or to perform less than I can, which suggests bad faith and indifference. On this particular occasion I was a prey to every form of nervousness, afraid of seeming tongue-tied if I said nothing, or shameless if I said much, with so weak a case.

hic ego tum ad respondendum surrexi: qua cura, di immortales! qua sollicitudine animi! quo timore! semper equidem magno cum metu incipio dicere: quotienscumque dico, totiens mihi videor in iudicium venire non ingenii solum, sed etiam virtutis atque officii, ne aut id profiteri videar, quod non possim, quod est impudentiae, aut non id efficere, quod possim, quod est aut perfidiae aut neglegentiae. tum vero ita sum perturbatus ut omnia timerem: si nihil dixissem, ne infantissimus, si multa in eius modi causa dixissem, ne impudentissimus existimarer.

How Do You Put Up With It?

J.P.V.D. Balsdon, Romans and Aliens (London: Duckworth, 1979), pp. 28-29, with note on p. 265:

After he had left Domitian's Rome in a huff, Florus set up as a schoolmaster at Tarraco in Spain. 'What a terrible shame,' his friends from Baetica said; 'how do you put up with sitting in school and teaching boys?' Florus answered that it had been hard at first, but that he had become a dedicated teacher.36Related posts:

36. ... Florus, Virgilius Orator 3, 2-3.

- The Joy of Teaching

- Thankless Uphill Work

- An Intellectual Botany Bay

- The Education of the Young

- Teacher's Lament

- A Hopeless Endeavor

- Teaching

- Lament for Diotimus

Sunday, August 28, 2022

A Confusing Sentence

Sarah F. Derbew, Untangling Blackness in Greek Antiquity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022),

p. 79, n. 33:

There are 7 volumes (8 if you count the supplement) of Keil's Grammatici Latini, so I don't know what "Grammatici Latini 757" refers to, without a volume number. Besides, Nonius Marcellus was not included in the Grammatici Latini collection. Nonius' De Compendiosa Doctrina was edited in 3 volumes by W.M. Lindsay.

Martin L. West, ed. and tr., Greek Epic Fragments (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2003), pp. 266-269, has one testimonium and three fragments from the epic Danais—in none of them do I see anything about the rearing of the Danaids. Here is fragment 1, preserved in Clement of Alexandria, Miscellanies 4.120.4:

From Christopher G. Brown:

Grammarian Nonius Marcellus Melanippus and the narrator of the early epic Danais describe the Danaids' rearing as abnormal and unfeminine (Grammatici Latini 757; fr. 1, as numbered in West [2003]).Nonius Marcellus' name is simply Nonius Marcellus, not Nonius Marcellus Melanippus, at least according to Martin Schanz and Carl Hosius, Geschichte der römischen Litteratur, 4.1: Die Litteratur des vierten Jahrhunderts, 2. Aufl. (Munich: C.H. Beck, 1914), pp. 142-148 (§ 826: Nonius Marcellus), who make no mention of Melanippus.

There are 7 volumes (8 if you count the supplement) of Keil's Grammatici Latini, so I don't know what "Grammatici Latini 757" refers to, without a volume number. Besides, Nonius Marcellus was not included in the Grammatici Latini collection. Nonius' De Compendiosa Doctrina was edited in 3 volumes by W.M. Lindsay.

Martin L. West, ed. and tr., Greek Epic Fragments (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2003), pp. 266-269, has one testimonium and three fragments from the epic Danais—in none of them do I see anything about the rearing of the Danaids. Here is fragment 1, preserved in Clement of Alexandria, Miscellanies 4.120.4:

And then swiftly the daughters of Danaus armed themselves in front of the fair-flowing river, the lord Nile.

καὶ τότ᾿ ἄρ᾿ ὡπλίζοντο θοῶς Δαναοῖο θύγατρες

πρόσθεν ἐϋρρεῖος ποταμοῦ Νείλοιο ἄνακτος.

From Christopher G. Brown:

I think that the reference is really to the lyric poet Melanippides (fr. 757 PMG), who seems to write that the Danaids did not have the feminine temper or might (οὐδὲ τὰν ὀργὰν [West : αὐτὰν MSS: ἀλκὰν Lloyd-Jones] γυναικείαν ἔχον). The text is pretty clearly corrupt (Page obelizes); there is a good commentary by M. Davies, Lesser and Anonymous Fragments of Greek Lyric Poetry (Oxford 2021) 76-78....[Y]ou can find a more extensive list of suggestions for Melanippides' text in M. Ercoles, Melanippidis Melii Testimonia et Fragmenta (Pisa and Rome 2021) fr. 1.D.L. Page, ed., Poetae Melici Graeci (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1962; rpt. 1967), p. 392 (#757): The fragment from Melanippides, tr. and ed. David A. Campbell:

For they did not bear the censure of mankind as a reproach, nor did they have a woman's temperament: in seated chariots they exercised in the sunny glades, often delighting their hearts in hunting, or again seeking out frankincense with its sacred tears and fragrant dates and the smooth Syrian grains of cassia.See also Alain Moreau, "Les Danaïdes de Mélanippidès: la femme virile," Pallas 32 (1985) 59, 61-90.

οὐ γὰρ ἀνθρώπων φόρευν μομφὰν ὄνειδος,

οὐδὲ τὰν ὀργὰν γυναικείαν ἔχον,

ἀλλ᾿ ἐν ἁρμάτεσσι διφρού-

χοις ἐγυμνάζοντ᾿ ἀν᾿ εὐ-

ήλι᾿ ἄλσεα πολλάκις

θήραις φρένα τερπόμεναι,

<αἱ δ᾿> ἱερόδακρυν λίβανον εὐώ-

δεις τε φοίνικας κασίαν τε ματεῦσαι

τέρενα Σύρια σπέρματα

1 Lloyd-Jones: μορφὰν cod. West: ἐνεῖδος cod.

2 West: τὰν αὐτὰν cod., τὰν ἀλκὰν Lloyd-Jones

3 Emperius: ασδεα cod. Page: πολλάκι cod.

4 Porson: θῆρες cod.

5 suppl. Page Emperius: -δακρυ, πατεῦσαι cod.

6 Fiorillo: συρίας τέρματα cod.

Labels: typographical and other errors

Easily Satisfied

Juvenal 5.6 (tr. G.G. Ramsay):

I know of nothing so easily satisfied as the belly.Lucan 4.373-381 (tr. J.D. Duff):

ventre nihil novi frugalius.

O Luxury, extravagant of resources and never satisfied with what costs little; and ostentatious hunger for dainties sought over land and sea; and ye who take pride in delicate eating—hence ye may learn how little it costs to prolong life, and how little nature demands. No famous vintage, bottled in the year of a long forgotten consul, restores these to health; they drink not out of gold or agate, but gain new life from pure water; running water and bread are enough for mankind.Related post: Bread and Water.

o prodiga rerum

luxuries numquam parvo contenta paratis

et quaesitorum terra pelagoque ciborum 375

ambitiosa fames et lautae gloria mensae,

discite, quam parvo liceat producere vitam

et quantum natura petat. non erigit aegros

nobilis ignoto diffusus consule Bacchus,

non auro murraque bibunt, sed gurgite puro 380

vita redit. satis est populis fluviusque Ceresque.

Saturday, August 27, 2022

Irritatingly Perverse

Peter Green, "Juvenal Revisited," Grand Street 9.1 (Autumn, 1989) 175-196 (at 181-182, with a typographical error fixed):

In those innocent days no one had as yet come forward to inform us, with peremptory assurance, that authorial intention was irrelevant, that the work was, literally, in the eye of the beholder, that critical reader-response and Rezeptionsgeschichte were what mattered, that judging the literary value of a poem or play in any abiding sense was a self-deluding mirage, that a menu or a seed catalogue could be deconstructed in just the same way as the Iliad, that the true creative artist was the translator, and that in any case the apparent "character" of author or narrator must always be viewed as a mere literary mask, a persona, an artificial manipulation of traditional formalized topoi, rhetorical clichés. Juvenal, as readers of Professor W.S. Anderson will know, has been no more immune than the next man to this kind of treatment. Though obviously useful to the extent of correcting excessive faith in what has been termed the "biographical fallacy," this entire movement (I have to make clear from the start) strikes me as not only misconceived but positively dangerous, destruction rather than deconstruction, moral and aesthetic nihilism winding up in a literary cul-de-sac, fueled by professional academic theorists with fond memories of the 1960s and a conscious or unconscious hatred of all creative art: intellectuals to whom the notions of absolute objective truth or sustainable moral value judgments are, for a variety of ideological reasons, pure anathema. When I ask myself whether creator or interpreter is more important in the ultimate scheme of things (and never mind the attempt to gussy up the status of interpretation by giving it the pseudo-Hellenistic label of "hermeneutics"), then I only have to ask myself which of the two could more easily survive without the other. Mistletoe needs oak; cuckoo must find nest; the parasite cannot exist apart from its involuntary host.Id. (at 182-183):

If literature is no part of the historical process but a mere intellectual game of which the rules can be refashioned by any player, wherein does its value lie, except as a suspect vehicle for academic careerism? And how can it be related to the beliefs and cultural evolution of the society that generated it, let alone to the individual whose vision drew it into being? Just how far this dissociative principle can go was lately demonstrated by a not overimaginative English classicist, who proved, to his own satisfaction, if not to that of any historian, by argumenta ex silentio and a list of putative geographical and climatic errors, that Ovid was in fact never exiled to Tomis at all, but simply sat in Rome for the last decade of his life playing with the rhetoric of exilic themes.The English classicist who argued that Ovid was never exiled is A.D. Fitton-Brown, "The Unreality of Ovid's Tomitan Exile," Liverpool Classical Monthly 10 (1985) 19-22, now followed by Michael Fontaine, "The Myth of Ovid's Exile," Electryone 6.1 (2018) 1-14.

I thus have two serious strikes against me: I am a historian, which means that I believe in the objective existence of truth, and have no great faith in the binding force of critical theory; and not only do I passionately love literature, but I never forget that it was written by real people, in an actual society, at a specific point in time. My position in academe thus somewhat recalls that of Juvenal's friend Umbricius (another character whose very existence has been doubted: Umbricius, umbra, the shadow-man), who asked: "What can I do in Rome? I never learnt how/ to lie. If a book is bad, I cannot puff it .../ astrological clap-trap/ is not in my stars." All signification is not relative, is not arbitrary. I do not regard it as the chief function of my profession to play literary games that generate their own rules. The retrojection of such modern theories, with a fine disregard for changing historical circumstance, on to ancient authors is something I have always found irritatingly perverse.

Friday, August 26, 2022

The Basic Necessities

Paul MacKendrick, The Mute Stones Speak: The Story of Archaeology in Italy, 2nd ed. (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1983), p. 132:

A healthy site, an orderly plan, a water supply, strong walls, housing, provision for political and religious needs: the basic necessities are all here, at Cosa, and all as early as the founding of the colony.Related post: Foundation of a New City.

A Little Too Close for Comfort

Peter Green, "Juvenal Revisited," Grand Street 9.1 (Autumn, 1989) 175-196 (at 175):

My acquaintance with Juvenal—Hamlet's "satirical rogue"—dates back, I am somewhat horrified to realize, almost half a century, so that his animadversions on the disadvantages of old age—the baboonlike wrinkles, the dripping noses, the ruined taste buds, the sluggish sexual performance (iacet exiguus cum ramice neruus), and what Shakespeare, embroidering as usual on the original, sums up as "a plentiful lack of wit, together with most weak hams"—have come, in the course of time, a little too close for comfort.The quotation is from Juvenal 10.205, omitted in most school editions (e.g. J.D. Duff's) and translated by Paul Murgatroyd as "your little penis with its varicocele lies there."

De Gustibus Non Est Disputandum

Aristophanes, Frogs 103-106 (tr. Stephen Halliwell):

HERAKLES. You actually like this stuff?W.B. Stanford ad loc.: K.J. Dover ad loc.:

DIONYSOS. It sends me crazy!

HERAKLES. It's a great big con-trick: you know very well that it is.

DIONYSOS. Don’t try to inhabit my mind—just live in your own.

HERAKLES. Everyone can see these things are a load of rubbish.

Ἡρ. σὲ δὲ ταῦτ᾽ ἀρέσκει;

Δι. μἀλλὰ πλεῖν ἢ μαίνομαι.

Ἡρ. ἦ μὴν κόβαλά γ᾽ ἐστίν, ὡς καὶ σοὶ δοκεῖ.

Δι. μὴ τὸν ἐμὸν οἴκει νοῦν· ἔχεις γὰρ οἰκίαν. 105

Ἡρ. καὶ μὴν ἀτεχνῶς γε παμπόνηρα φαίνεται.

Thursday, August 25, 2022

The Fatherland

Thomas Mann, The Magic Mountain, chapter 4 (tr. James E. Woods; he = Settembrini):

Adolph Menzel, Im Biergarten (Schweinfurt, Museum Georg Schäfer)

"Beer, tobacco, and music," he said. "Behold the Fatherland."

»Bier, Tabak und Musik«, sagte er. »Da haben wir Ihr Vaterland!«

The Deplorables

J.P.V.D. Balsdon, Romans and Aliens (London: Duckworth, 1979), p. 25, with note on p. 265:

At the bottom of the social scale, below even the provincial, was the rusticus, the country bumpkin whom, universally, the city-dweller despised. 'Uncultured rustic clots like you,' Apuleius shouted at his prosecutor; 'uti tu es, inculti et agrestes.' Were such people men, or were they animals, Cicero asked?23Id., p. 38, with note on p. 265:

23. Apul., Apol. 23; Cic., Phil. 8, 9.

We have Ammianus Marcellinus' description of the top Roman senatorial society which he found in the fourth century AD. Rich, narrow-minded, uncultured and conceited, its members looked down their noses at an outsider, even a respectable outsider like Ammianus himself. 'Inanes flatus quorundam vile esse quicquid extra urbis pomerium nascitur aestimant', 'There are people who, with empty bombast, treat anything born outside the city as simple dirt'.38

38. AM 14, 6 (14, 6, 22 quoted in text); 28, 4.

The Professional Student

Goethe, Faust, Part II, lines 6637-6641 (tr. David Luke):

Mikhail Bakhtin, The Duvakin Interviews, 1973, tr. Margarita Marinova (Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press, 2019), pp. 69-70:

As your old mossy pate can yet apprize me,The same, tr. Stuart Atkins:

You're still a student. What else can you do

But just read on! That's scholarship for you!

One builds a modest card-house, there to sit;

Even great minds never quite finish it.

Ich weiß es wohl: bejahrt und noch Student,

Bemooster Herr! Auch ein gelehrter Mann

studiert so fort, weil er nicht anders kann.

So baut man sich ein mäßig Kartenhaus,

der größte Geist baut's doch nicht völlig aus.

I know the type—the student who keeps on

until he's middle-aged! But even learned men

continue studying because of some compulsion.

That's how a shabby house of cards is often started

which even the best mind cannot complete.

Mikhail Bakhtin, The Duvakin Interviews, 1973, tr. Margarita Marinova (Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press, 2019), pp. 69-70:

B: There were some very old students. There was no limit ... you could keep studying ...Friedrich Strehlke, Wörterbuch zu Goethe's Faust (Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1891), p. 15:

D: That's ridiculous!

B: Yes. If you could pay to keep studying, that's all that mattered.

D: Don't you think that's ridiculous?

B: There were certainly some minuses, but also pluses to the system. There were some old students, who never really attended classes, but wanted some kind of status in life, so they became eternal students. That's what they were called, "eternal students." It was the same situation in Germany, even more so. You were given a general student gradebook, "a matricula card." You could study one subject at one university, another — somewhere else, a third one at a third, and it was all legal.

D: So there was no concept of "university year" — freshman, sophomore, etc. — and moving up each year?

B: There was, there was, but it was a formality. Usually what mattered was how many years you spent studying — three years meant you were a third-year student ...

D: And what if you studied there for eight years? Were you supposed to be an eight-year student?

B: We didn't count beyond the usual years ... "He is a perpetual exam taker ..." or "This student has a tail ...," as we used to say.

D: So there were students with "tails"?

B: Right. For example, someone could study for five or six years, but still have many "tails," that is, exams he hasn't passed. In Germany, you could take exams in any subject at any university you wanted. That was great, because there were different professors at different schools. Everybody wanted to take a course with the most famous, the best professor at the time, so they went ...

D: ... to his particular university.

B: Yes. And moved somewhere else from there. They also had those students, the kind we called "eternal students." But they had a different name for them: "bemooster Herr," that means "hairy face" ...

D: You mean with a beard?

B: No, wait, here is a better translation. "Moos," "Bemooster Herr." Covered in moss! Moss. Yes. That's the best expression, a mossy student, someone covered with moss. We called them "old students" or "eternal students."

bemoost, 6638, bemooster Herr. Das bekannte Studentenlied von G. Schwab: „Bemooster Bursche zieh' ich aus“ ist schon von 1814, also viel älter als der zweite Theil von Faust.

Labels: opsimathy

Wednesday, August 24, 2022

Stuff Yourself

Juvenal 4.67 (tr. G.G. Ramsay):

Hasten to fill out thy belly with good things.Paul Wessner, ed., Scholia in Iuvenalem Vetustiora (Leipzig: B.G. Teubner, 1931), p. 59 (text and supplement): Edward Courtney, A Commentary on the Satires of Juvenal (1980; rpt. Berkeley: California Classical Studies, 2013), p. 182:

propera stomachum laxare sagina.

sagina Weidner et cod. Vat. Reg. 2029: saginam Ρ1R lem.: saginis VΦ: sagittis F et Probus Vallae: saginae Jahn (et saginis et sagittis agnoscit schol.)

[W]e again have Juvenal's favourite humour through incongruity. The word SAGINA will have been familiar to the fisherman from his trade; it means the small fry which feeds large fish (Varro RR 3.17.7, where it is also described as plebeiae cenae pisces; Pliny NH 9.14). There is a play on animum laxare, where the verb is metaphorical.Some scholars, however, understand the command in precisely the opposite meaning, not stuff your stomach with the fish, but rather purge your stomach of its contents to make room for the fish. See e.g. Biagio Santorelli, ed., Giovenale, Satira IV. Introduzione, Traduzione e Commento (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2012), pp. 102-103: Oxford Latin Dictionary, s.v. sagīna: Alfred Ernout and Alfred Meillet, Dictionnaire étymologique de la langue latine, 4th ed. rev. Jacques André (Paris: Klincksieck, 2001), p. 588 (s.v. sagīna):

Les langues romanes suppose un doublet sagīnum (et *sagīmen). M.L. 7506; B.W. saindoux [= lard]....Aucune étymologie. Terme technique.There is no entry for sagina in Michiel de Vaan, Etymological Dictionary of Latin and the Other Italic Languages (Leiden: Brill, 2008).

Budget Cuts

Tuesday, August 23, 2022

A Series of Dark Lines

Dante, Inferno 21.139 (he = the devil Malacoda; tr. John D. Sinclair):

And he made a trumpet of his rear.F. Lippmann, ed., Zeichnungen von Sandro Botticelli zu Dantes Göttlicher Komödie, 2. Aufl. (Berlin: G. Grote'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1921), unnumbered page, illustration for Inferno XXI (note lower right-hand corner): Paul Barolsky, "Dante's Infernal Fart and the Art of Translation," Arion 22.1 (Spring/Summer 2014) 93-101 (at 98):

ed elli avea del cul fatto trombetta.

At the right side of this diabolical band we see the devil that is unmistakably Malacoda. I say unmistakably, because Botticelli has depicted the black hole of the demon, what some translators refer to as his "asshole," and from it he pictures a series of dark lines that convey a rush of wind. These horizontal "motion-lines," that issue from the devil's buttocks become a kind of coda.

Labels: noctes scatologicae

Bestial Cruelty

Fyodor Dostoyevsky, The Brothers Karamazov, Part II, Book V, Chapter 4 (tr. Constance Garnett):

People talk sometimes of bestial cruelty, but that's a great injustice and insult to the beasts; a beast can never be so cruel as a man, so artistically cruel.

Monday, August 22, 2022

Lament for Diotimus

Greek Anthology 11.437 (by Aratus; tr. W.R. Paton, with his note):

Hermann Beckby ad loc. (with my additions):

Related posts:

I lament for Diotimus,1 who sits on stonesThe children of Gargarus, i.e., the children of the inhabitants of Gargarus (or Gargara).

repeating Alpha and Beta to the children of Gargarus.

1 The epigram is not meant to be satirical. Diotimus was a poet obliged to gain his living by teaching in an obscure town.

αἰάζω Διότιμον, ὃς ἐν πέτραισι κάθηται,

Γαργαρέων παισὶν βῆτα καὶ ἄλφα λέγων.

Hermann Beckby ad loc. (with my additions):

Nach Stephanos von Byzanz [s.v. Γάργαρα, vol. I, pp. 408-409 Billerbeck] handelt es sich um Diotimos von Adramyttion. Zum Anfang vgl. VIII 739. Gargara: Stadt in der Troas. Nach Reitzenstein [Epigramm und Skolion, p. 171] ist das Ep. ein Spottepitaph auf den Lebenden (s. VII 739, 1 und zu VII 408). Nach Hecker [Commentationis Criticae de Anthologia Graeca Pars Prior, pp. 21-22] ist das Ep. kein Spott, sondern eine Art Empfehlung für ihn an König Antigonos. Diotimos war vielleicht infolge der Keltenkriege in Not geraten. Nach Macrobius [5,20,8] stammen die Verse aus einer Elegie. Zum Schluß vgl. Horaz Epist. I,20,17: pueros elementa docentem; Lukian Gall. 23: παιδία συλλαβίζειν διδάσκων.See also Paul Schubert, "A propos d'une épigramme d'Aratos sur Diotimos," Hermes 127.4 (1999) 501-503.

Related posts:

- The Joy of Teaching

- Thankless Uphill Work

- An Intellectual Botany Bay

- The Education of the Young

- Teacher's Lament

- A Hopeless Endeavor

- Teaching

Unspotted From the World

Walter Hooper, introduction to C.S. Lewis, Present Concerns (San Diego: Harcourt, Inc., 1987), p. 7:

The phrase "unspotted from the world" comes from James 1:27 (KJV):

"Who is Elizabeth Taylor?" asked C.S. Lewis. He and I were talking about the difference between "prettiness" and "beauty", and I suggested that Miss Taylor was a great beauty. "If you read the newspapers," I said to Lewis, "you would know who she is." "Ah-h-h-h!" said Lewis playfully, "but that is how I keep myself 'unspotted from the world'." He recommended that if I absolutely "must" read newspapers I have a frequent "mouthwash" with The Lord of the Rings or some other great book.

The phrase "unspotted from the world" comes from James 1:27 (KJV):

Pure religion and undefiled before God and the Father is this, To visit the fatherless and widows in their affliction, and to keep himself unspotted from the world.

θρησκεία καθαρὰ καὶ ἀμίαντος παρὰ τῷ θεῷ καὶ πατρὶ αὕτη ἐστίν, ἐπισκέπτεσθαι ὀρφανοὺς καὶ χήρας ἐν τῇ θλίψει αὐτῶν, ἄσπιλον ἑαυτὸν τηρεῖν ἀπὸ τοῦ κόσμου.

Sunday, August 21, 2022

A Good Journey

Sophocles, Philoctetes 641 (tr. R.C. Jebb):

'Tis ever fair sailing, when thou fleest from evil.

ἀεὶ καλὸς πλοῦς ἔσθ᾽, ὅταν φεύγῃς κακά.

KWFA PROSWPA

Aristophanes, Clouds, Wasps, Peace. Edited and Translated by Jeffrey Henderson (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998 = Loeb Classical Library, 488), p. 426 (in the Dramatis Personae for Peace):

kwfa proswpaThis a mistake for ΚΩΦΑ ΠΡΟΣΩΠΑ (i.e. non-speaking characters). See pp. 8 and 220. And yes, I know what caused the mistake—something like this: A friend once called me Λοεβομάστιξ (Loebomastix, i.e. castigator of the Loeb Classical Library; cf. Ὁμηρομάστιξ = Homeromastix).

Labels: typographical and other errors

A Pair of Fools

Sebald Beham (1500-1550), A Couple of Fools (British Museum, accession number 1892,0628.185):

Margaret A. Sullivan, "Fools/Folly," in Helene E. Roberts, ed., Encyclopedia of

Comparative Iconography, Vol. 1 (Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 1998), pp. 331-336 (at 331):

When a bladder is substituted for the traditional bauble, as in Hans Sebald Beham's small print (circa 1530) of a male fool seated on the ground next to a female fool, its phallic shape emphasizes his inability to control his sexual appetites, a failing that further associates the fool with animals. Grotesque features such as a big nose, large lips, crossed eyes, or some other deformity that is the antithesis of a desirable physiognomy also characterize the imagery of the fool and are used to mark the fool as a deviant.Charles Zika, The Appearance of Witchcraft: Print and Visual Culture in Sixteenth-Century Europe (2007; rpt. London: Routledge, 2009), pp. 76-77 (notes omitted):

Murner's image, for instance, probably alluded to contemporary use of the German word for pot or cauldron, Hafen or Häfelin, for the vagina. The association was not just limited to language, but also related to communal practices. On the feast of St. John in southern Germany, for instance, unmarried women would hang from the eaves of their houses small pots filled with rose petals, with a burning candle inside. The pot symbolized the vagina and so the hanging of these pots at mid-summer marked a woman's sexual fertility and availability. It is not surprising, therefore, that the pot, vase or vessel was frequently used pictorially to represent female sexuality, most graphically and obviously so in a small engraving of Two Fools by Sebald Beham, in which a phallic stick held by the male fool is matched by the vessel held by the female.John H. Astington, Stage and Picture in the English Renaissance: The Mirror up to Nature (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), p. 103:

The print shows a male and female fool sitting facing each other, drinking. They both wear the traditional headgear of the Brant tradition, and their lascivious interest each in the other is signalled not only by their poses, each leaning forward, but by the prominent left foreground detail of the phallic 'bauble' the male figure holds in his right hand, made of leather or cloth, and stuffed to take on its characteristic shape, not unlike the ancient costumes worn by Greek actors in comedies. The flies around the heads of the two figures are symbols of their corruption, animality, and empty-headedness. The drinking vessels — the flask held by the man, with its projecting spout, and the prominently shaded mouth of the flagon in the right lower foreground, at the same level as the woman's thighs — further symbolise the lechery of the encounter ...

Saturday, August 20, 2022

Theta and Zeta

I just encountered theta and zeta as nouns in Walter of Wimborne's Ave Virgo Mater Christi, in his Poems, ed. A.G. Rigg (Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 1978), pp. 146-147.

Theta isn't in Alexander Souter, A Glossary of Later Latin to 600 A.D. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1949), Albert Blaise, Lexicon Latinitatis Medii Aevi (Turnhout: Brepols, 1975), or J.F. Niermeyer, Mediae Latinitatis Lexicon Minus (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1976). Rigg ad loc. refers to Isidore of Seville (560-636), Etymologies 1.3.8 (tr. Stephen A. Barney et al.):

Zeta, on the other hand, is in all the dictionaries just cited, with the meaning diaeta = house.

Theta isn't in Alexander Souter, A Glossary of Later Latin to 600 A.D. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1949), Albert Blaise, Lexicon Latinitatis Medii Aevi (Turnhout: Brepols, 1975), or J.F. Niermeyer, Mediae Latinitatis Lexicon Minus (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1976). Rigg ad loc. refers to Isidore of Seville (560-636), Etymologies 1.3.8 (tr. Stephen A. Barney et al.):

There are also five mystical letters among the Greeks. The first is ϒ, which signifies human life, concerning which we have just spoken. The second is Θ, which [signifies] death, for the judges used to put this same letter down against the names of those whom they were sentencing to execution. And it is named 'theta' after the term θάνατος, that is, 'death.' Whence also it has a spear through the middle, that is, a sign of death. Concerning this a certain verse says:Walter of Wimborne used theta in the phrase theta tetre mortis, i.e. the death of death.How very unlucky before all others, the letter theta.Quinque autem esse apud Graecos mysticas litteras. Prima ϒ, quae humanam vitam significat, de qua nunc diximus. Secunda Θ, quae mortem [significat]. Nam iudices eandem litteram adponebant ad eorum nomina, quos supplicio afficiebant. Et dicitur Theta ἀπὸ τοῦ θανάτου, id est a morte. Vnde et habet per medium telum, id est mortis signum. De qua quidam:O multum ante alias infelix littera theta.

Zeta, on the other hand, is in all the dictionaries just cited, with the meaning diaeta = house.

Saint Erasmus

Dedication of Jeff Persels and Russell Ganim, edd.,

Fecal Matters in Early Modern Literature and Art: Studies in Scatology

(2004; rpt. London: Routledge, 2016):

Related post: The Company of Saints.To Erasmus, patron saint of intestinal disorders

Ora pro nobis.

Friday, August 19, 2022

Food Fit for Sheep

Greek Anthology 11.413 (by Ammianus; tr. W.R. Paton):

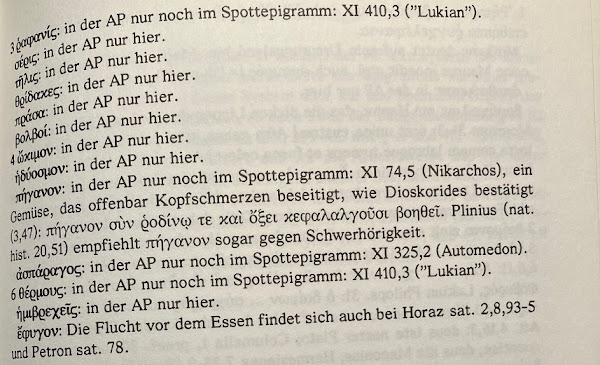

Thanks very much to Michael Hendry for sending me a photocopy of the relevant pages of Hendrich Schulte, Die Epigramme des Ammianos: Text, Übersetzung, Kommentar (Trier: Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier, 2004):

Apelles gave us a supper as if he had butchered a garden,The same, tr. H.C.I. Gwynne-Vaughan and F.A. Wright:

thinking he was feeding sheep and not friends.

There were radishes, chicory, fenugreek, lettuces, leeks, onions,

basil, mint, rue, and asparagus.

I was afraid that after all these things he would serve me with hay,

so when I had eaten some half-soaked lupins I went off.

ὡς κῆπον τεθυκὼς, δεῖπνον παρέθηκεν Ἀπελλῆς,

οἰόμενος βόσκειν ἀντὶ φίλων πρόβατα.

ἦν ῥαφανίς, σέρις ἦν, τῆλις, θρίδακες, πράσα, βολβοί,

ὤκιμον, ἡδύοσμον, πήγανον, ἀσπάραγος·

δείσας δ᾽ ἐκ τούτων μὴ καὶ χόρτον παραθῇ μοι,

δειπνήσας θέρμους ἡμιβρεχεῖς, ἔφυγον.

He went among his garden rootsSee Friedrich Marx, C. Lucilii Carminum Reliquiae, Vol. II: Commentarius (Leipzig: B.G. Teubner, 1905), pp. 81-82 (on fragment 193), and Francesco Citti, "La Gola Frustrata: Invitati Delusi da Plauto ad Ammiano Epigrammatista," Lexis 9-10 (1992) 163-175.

And took a knife and cut their throats;

Then served us greenstuff, heap on heap,

As though his guests were bleating sheep.

Rue, lettuce, onion, basil, leek,

Radishes, chicory, fenugreek,

Asparagus and peppermint,

And lupines boiled—he made no stint.

At last in fear I came away:

I thought the next course would be hay.

Thanks very much to Michael Hendry for sending me a photocopy of the relevant pages of Hendrich Schulte, Die Epigramme des Ammianos: Text, Übersetzung, Kommentar (Trier: Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier, 2004):

Surprise

J.P.V.D. Balsdon, Romans and Aliens (London: Duckworth, 1979), p. x:

A learned friend of mine expressed surprise at the antiquity of some of the books which I quote; these are in the main doctorate dissertations of the nineteenth century, the sort of work which, with its close concentration of interest on the subject in hand, never seems to me to lose its value. Scholars have grown no cleverer in the last hundred years; it is simply that they have more (particularly in the way of inscriptions and papyri) to be clever about.

Thursday, August 18, 2022

Strange Tricks

M.I. Finley, The World of Odysseus, 2nd ed. (1965; rpt. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1983), p. 17:

The human mind plays strange tricks with time perspectives when the distant past is under consideration: centuries become as years and millennia as decades. It requires conscious effort to make the necessary correction ...

The Eloquence of the Manager of a Freak Show

Greek Anthology 11.353 (by Palladas; tr. W.R. Paton, with his note):

Jean François Boissonade ap. Friedrich Dübner, Epigrammatum Anthologia Palatina, Vol. II (Paris: Firmin Didot, 1888), p. 388:

Alfred Franke, De Pallada Epigrammatographo (Leipzig: Hesse & Becker, 1899), p. 82:

Wulf D. Hund, "Racist King Kong Fantasies: From Shakespeare's Monster to Stalin's Ape-Man," in Wulf D. Hund et al., edd., Simianization: Apes, Gender, Class, and Race (Vienna: LIT Verlag, 2015), pp. 43-73 (at 45-46, with mention of Palladas in n. 8):

Hermolycus' daughter slept with a great ape and she gave birth to many little ape-Hermeses. If Zeus, transformed into a swan, got him from Leda Helen, Castor, and Pollux, with Hermione at least a crow lay, and, poor woman, she gave birth to a Hermes-crowd of horrible demons.2Paton's translation is awkward. I would revise it slightly as follows:

2 The epigram seems very confused. Is Hermione the same as Hermolycus' daughter, and how did she manage to have such a variety of husbands?

Ἑρμολύκου θυγάτηρ μεγάλῳ παρέλεκτο πιθήκῳ·

ἡ δ᾽ ἔτεκεν πολλοὺς Ἑρμοπιθηκιάδας.

εἰ δ᾽ Ἑλένην ὁ Ζεὺς καὶ Κάστορα καὶ Πολυδεύκην

ἐκ Λήδης ἔτεκεν, κύκνον ἀμειψάμενος,

Ἑρμιόνῃ γε Κόραξ παρελέξατο· ἡ δὲ τάλαινα

φρικτῶν δαιμονίων ἑρμαγέλην ἔτεκεν.

Hermolycus' daughter slept with a great ape and she gave birth to many little ape-Hermeses. If Zeus, transformed into a swan, begat Helen, Castor, and Pollux from Leda, with Hermione at least a crow lay, and, poor woman, she gave birth to a Hermes-crowd of horrible demons.This epigram seems to have attracted little notice among scholars. Some subsidia interpretationis follow.

Jean François Boissonade ap. Friedrich Dübner, Epigrammatum Anthologia Palatina, Vol. II (Paris: Firmin Didot, 1888), p. 388:

CCCLIII. In Plan. ἄδηλον. — In quandam deformium liberorum matrem. — 1. «Hermolyci filia Hermione deformi viro concumbebat; nam sic est πιθήκῳ capiendum; conf. ad ep. 196. — 2. Nomen tanquam ex avi et patris nomine compositum. — 5. Dixerat cum simia rem habuisse; nunc cum corvo dicit, non nitide; nec Ἑρμαγέλη exspectatur post Ἑρμοπιθηκιάδας: ut crediderim esse confusa duo epigrammata, quorum prius primo disticho includatur. — 6. Ἑρμαγέλη, grex quem pascat Mercurius larvarum praeses.» B. Omnia integra, neque ea lance expendendus Palladas.In other words, Boissonade thought there were two separate epigrams (lines 1-2 and 3-6), not one.

Alfred Franke, De Pallada Epigrammatographo (Leipzig: Hesse & Becker, 1899), p. 82:

Constat inter omnes horum saeculorum, quae commemoravi, poetas in primis Nonnum et eius sectatores maxime valuisse novis verbis fictis. In Palladae quoque epp. multa invenimus nova verba haud parva cum sagacitate ficta aut parodiae aut annominationis causa. De nominibus propriis certis de causis fictis iam supra dixiiuus, addimus hoc loco alia: ... praeterea Ἑρμοπιθηκιάδης et ἑρμαγέλη comice fingit secundum Ἑρμόλυκος ep. XI. 353.Id., pp. 83-84 (footnotes omitted):

Particulas quoque, quae saeculis Ch. n. sequentibus in dies rarescebant, apud Palladam perraras esse observamus. Ex eis particulis, quas Blass in Novo Testamento non iam exstare explicavit, perpaucae in epp. Palladae reperiuntur ... γὲ coniunctum legitur et apud Parthenium et reliquos eroticos plane desideratur, semel inveni in Palladae ep. XI. 353, 5., quo loco cum etiam propter sententiarum conexum suspicionem moveat, fortasse rectius in δὲ mutandum est.Georg Luck, "Palladas: Christian or Pagan?" Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 63 (1958) 455-471 (at 467, with note on p. 470):

His eloquence is, indeed, the eloquence of the manager of a freak show70; he does not have to appeal to moral standards in order to attract his public.Heather White, "Eight Convivial and Satirical Epigrams," Minerva. Revista de filología clásica 11 (1997) 67-71 (at 70):

70 Cf. Anth. Pal. 11.353.

In this epigram Hermolycus' daughter (i.e. Hermione) is said to have slept with an ape and produced ugly children. For the fact that apes were considered ugly cf. A.P. XI, 196. The poet then states that if Zeus transformed himself into a swan in order to produce beautiful children, then Hermione must have slept with a crow in order to produce her children. For the comparison between the beautiful white swan and the ugly black crow cf. Callimachus fr. 260,56 ff.Of course Hermolycus' daughter didn't literally sleep with an ape and produce offspring. On the first line πιθήκῳ probably refers to "a despicable or ugly person": see Franco Montanari, The Brill Dictionary of Ancient Greek (Leiden: Brill, 1995),p. 1663, where this passage is not cited, however. I wonder if perhaps Πίθηκος could be a name or nickname here. Pithecium is a proper name in Plautus, Truculentus 477.

Wulf D. Hund, "Racist King Kong Fantasies: From Shakespeare's Monster to Stalin's Ape-Man," in Wulf D. Hund et al., edd., Simianization: Apes, Gender, Class, and Race (Vienna: LIT Verlag, 2015), pp. 43-73 (at 45-46, with mention of Palladas in n. 8):

Aware of the Spanish atrocities in America and the Portuguese slave trading in Africa, Bodin opposes slavery.7 But at the same time he is equipped with the racist knowledge of his era. On the one side it is traditional, peopled by devils and witches. Satan appears as ›God's ape‹ and seduces sinners full of carnal desire. Unsurprisingly, in this ambience women mix with apes. Respective evidence dates back to the eleventh century. The cardinal and Doctor of the Church Peter Damian has already told the story about the spouse of a count from Liguria whose playmate was a monkey as lecherous as herself. Thus the atrocity happened: »com [sic, read cum] femina fera concubuit« — the woman copulated with the animal.8 After that the monkey, looking on the husband as a rival, mangled him with claws and teeth. On top of that, a child arose from this liaison that was described not as a bestial but as an infernal monstrosity.9Could the consort of Hermolycus' daughter be an Aethiops? If so, then the note of Lindsay Watson and Patricia Watson on Juvenal 6.599-600 may be relevant:

7 Cf. Henry Heller: Bodin on Slavery and Primitive Accumulation; Claudia Opitz-Belakhal: Das Universum des Jean Bodin, pp. 86-89.

8 Petrus Damianus: Opera, p. 143; cf. Alfred Adam: Der Teufel als Affe Gottes; Horst W. Janson: Apes and Ape Lore in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, p. 268; Samuel G. Armistead, James T. Monroe, Joseph H. Silverman: Was Calixto's Grandmother a Nymphomaniac Mamlūk Princess?, refer to similar motifs in Fernando de Rojas' ›La Celestina‹ and the ›Arabian Nights‹. The Greek Anthology records an earlier epigram of Palladas who asserted: »Hermolycus' daughter slept with a great ape and she gave birth to many little ape-Hermeses« (XI, 353, p. 237).

9 At that time the ape's immortal soul presumably had disappeared which on the way from Augustine to Thomas Aquinas definitely got lost (see Richard Sorabji: Animal Minds and Human Morals, pp. 201 f.). Admittedly an ape may have had the right to court proceedings, but »medieval animals fared badly when facing trial« (Jan Bondeson: Animals on Trial, p. 135).

The Roman matrona who gave birth to an Aethiops was a theme in declamation (Balsdon 1979: 218). Martial jests upon the topic (6.39.6-9); Plin. HN 7.51, Arist. Gen. an. 722a10-11 and Plut. De sera 563a report the procreative results ...Balsdon 1979 = J.P.V.D. Balsdon, Romans and Aliens (London: Duckworth, 1979), where most of the relevant information is in n. 29 (p. 294). To the references adduced by the Watsons add Claudian, The War Against Gildo 1.188-193.

Wednesday, August 17, 2022

Praise and Blame

Salvian, On the Governance of God 8.1.1 (tr. Jeremiah F. O'Sullivan):

In a way, all wish to be praised. Reproof is pleasing to nobody. What is much worse, no matter how bad, no matter how depraved a man, he prefers to be lauded in a lying manner than reproved in a right manner. He prefers to be deceived by the mockery of false praise, rather than made whole by the most healthful advice.

omnes enim admodum se laudari volunt; nulli grata reprehensio est. immo, quod peius multo est, quamlibet malus, quamlibet perditus, mavult mendaciter praedicari quam iure reprehendi et falsarum laudum inrisionibus decipi quam saluberrima admonitione salvari.

No Longer Communities

Donald Davidson, "Some Day, in Old Charleston," in his Still Rebels, Still Yankees and Other Essays (1957; rpt. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1972), pp. 213-227 (at 226):

Communities that accept such perversions of the beautiful and the gallant are no longer communities in any true sense. They have passed into a state of social disequilibrium and instability that makes them exceedingly dangerous. If they do not know what use ought to be made of beauty and gallantry, and, still worse, do not care what use is made of these so long as impressive material results are obtained, there is nothing to stop them from perverting and using as an instrument of power anything that can be so perverted and used. They are mobs, made vastly more dangerous than the ordinary spontaneous mob because, though spiritually mobs, they retain the rational organization supplied to them by science and education, and can thus use chaos itself as a form of power.

Good Health

Lucian, A Slip of the Tongue in Greeting 11 (tr. K. Kilburn):

Then Pyrrhus of Epirus also is worthy of mention. As a general he was second only to Alexander and endured a myriad changes of fortune. In all his prayers to the gods and sacrifices and offerings he never asked them for victory or increased kingly dignity or glory or excessive wealth; his prayer was for this thing alone—good health; he was sure that if he had this he would easily get all the rest. I think he was right when he considered that all the blessings in the world are worth nothing when health is the one thing he hasn't got.

ἄξιον δὲ καὶ Πύρρου τοῦ Ἠπειρώτου μνησθῆναι, ἀνδρὸς μετὰ Ἀλέξανδρον τὰ δεύτερα ἐν στρατηγίαις ἐνεγκαμένου καὶ μυρίας τροπὰς τῆς τύχης ἐνεγκόντος. οὗτος τοίνυν ἀεὶ θεοῖς εὐχόμενος καὶ θύων καὶ ἀνατιθεὶς οὐδεπώποτε ἢ νίκην ἢ βασιλείας ἀξίωμα μεῖζον ἢ εὔκλειαν ἢ πλούτου ὑπερβολὴν ᾔτησε παρ᾽ αὐτῶν, ἀλλ᾽ ἓν τοῦτο ηὔχετο, ὑγιαίνειν, ὡς ἔστ᾽ ἂν τοῦτ᾽ ἔχῃ, ῥᾳδίως αὐτῷ τῶν ἄλλων προσγενησομένων. καὶ ἄριστα, οἶμαι, ἐφρόνει, λογιζόμενος ὅτι οὐδὲν ὄφελος τῶν ἁπάντων ἀγαθῶν, ἔστ᾽ ἂν τοῦ ὑγιαίνειν μόνον ἀπῇ.

The Isolated Worker

A.G. Sertillanges (1863-1948), The Intellectual Life, tr. Mary Ryan (Westminster: The Newman Press, 1960), p. 9:

The same is true of the isolated worker, deprived of intellectual resources and stimulating society, buried in some little provincial spot, where he seems condemned to stagnate, exiled far from rich libraries, brilliant lectures, an eagerly responsive public, possessing only himself and obliged to draw solely on that inalienable capital.Maurice Platnauer, review of John Jackson, Marginalia Scaenica (London: Oxford University Press, 1955), in Classical Review 6.2 (June, 1956) 112-115 (at 112):

The greater part of Jackson's life was spent not in the studious seclusion of a university but in a remote village in the wilds of Cumberland, where he managed his mother's farm, his reading and writing being of necessity done on his return from the day's work. He was further inhibited by having no public library to which to go for new editions or books of reference, and by the fact that his own texts and commentaries were neither very numerous nor always up to date; yet he has produced a collected body of emendations the like of which, at least for brilliance and ingenuity, has not seen the light of day since the publication of Madvig's Adversaria and Cobet's Variae and Novae Lectiones more than a century ago.

Tuesday, August 16, 2022

Wholesale Condemnation of Africans

I don't see Salvian of Marseille mentioned in the index of Benjamin Isaac, The Invention of Racism in Classical Antiquity (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004; rpt. 2006), although his book covers a wide

chronological range,

"from the fifth century B.C. till late antiquity" (p. 2). The seventh book of Salvian's On the Governance of God is full of condemnations of Africans. I've selected just a few examples below.

7.13.57 (tr. Jeremiah F. O'Sullivan):

7.13.57 (tr. Jeremiah F. O'Sullivan):

But in almost all Africans, insofar as it pertains to both, that is, being equally good and evil, there is no balance, because almost the whole population is evil. After the purity of their original nature has been cut off, vice has created in them, as it were, another nature.7.15.63-64:

in Afris vero paene omnibus nihil horum est, quod ad utrumque pertineat, id est bonum aeque ac malum, quia totum admodum malum. adeo exclusa naturae originalis sinceritate aliam quodammodo in his naturam vitia fecerunt.

As all dirt flows into the bilge in the bowels of a ship, so vices flowed into the African way of life, as if from the whole world. I know of no baseness which did not abound there. Even though pagans and wild peoples have their own special vices, yet, all their crimes do not merit reproach.7.18.80:

The Gothic nation is lying, but chaste. The Alani are unchaste, but they lie less. The Franks lie, but they are generous. The Saxons are savage in cruelty, but admirable in chastity. In short, all peoples have their own particular bad habits, just as they have certain good habits. Among almost all Africans, I know not what is not evil. If they are to be accused of inhumanity, they are inhuman; if of drunkenness, they are drunkards; if of forgery, they are the greatest of forgerers; if of deceit, they are the most deceitful; if of cupidity, they are the most greedy; if of treachery, they are the most treacherous.

nam sicut in sentinam profundae navis conluviones omnium sordium, sic in mores eorum quasi ex omni mundo vitia fluxerunt. nullam enim improbitatem scio quae illic non redundaverit; cum utique etiam paganae ac ferae gentes etsi habeant specialiter mala propria, non sint tamen in his omnia exsecratione digna.

Gothorum gens perfida, sed pudica est; Alanorum impudica, sed minus perfida; Franci mendaces, sed hospitales; Saxones crudelitate efferi, sed castitate mirandi. omnes denique gentes habent, sicut peculiaria mala, ita etiam quaedam bona. in Afris paene omnibus nescio quid non malum. si accusanda est inhumanitas, inhumani sunt; si ebrietas, ebriosi; si falsitas, fallacissimi; si dolus, fraudulentissimi; si cupiditas, cupidissimi; si perfidia, perfidissimi.

Who could believe or even hear that men converted to feminine bearing not only their habits and nature, but even their looks, walk, dress, and everything that is proper to the sex or appearance of a man? Therefore, everything was put contrariwise, so that, since nothing should be more shameful to men than if they seem to have something feminine about them, in Carthage nothing seemed worse to certain men than to have something masculine about them.Somewhat milder is the anonymous Expositio Totius Mundi et Gentium 17.61 Rougé p. 202 (tr. Jesse Earle Woodman):

quis credere aut etiam audire possit, convertisse in muliebrem tolerantiam viros non usum suum tantum atque naturam, sed etiam vultum, incessum, habitum, et totum penitus quicquid aut in sexu est aut in usu viri: adeo versa in diversum omnia erant, ut cum viris nihil magis pudori esse oporteat, quam si muliebre aliquid in se habere videantur , illic nihil viris quibusdam turpius videretur, quam si in aliquo viri viderentur.

Africa itself is very great, good, and rich, but the men which it produces are not worthy of their native land. While the land is great and good, its men are definitely not. They are said to be extremely treacherous, saying one thing and doing another. it is difficult to find a good man among them, although it is possible that there are a few good ones among their large numbers.

ipsa autem regio Africae est valde maxima et bona et dives, homines autem habens non dignos patriae; regio enim multa et bona, homines vero non sic. dolosi enim quam plurime omnes esse dicuntur, alia quidem dicentes, alia autem facientes. difficile autem inter eos invenitur bonus; tamen in multis pauci boni esse possunt.

Monday, August 15, 2022

Distinctions

Paul, Letter to the Galatians 3:28 (KJV):

There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither bond nor free, there is neither male nor female: for ye are all one in Christ Jesus.F.F. Bruce ad loc.:

οὐκ ἔνι Ἰουδαῖος οὐδὲ Ἕλλην, οὐκ ἔνι δοῦλος οὐδὲ ἐλεύθερος, οὐκ ἔνι ἄρσεν καὶ θῆλυ· πάντες γὰρ ὑμεῖς εἷς ἐστε ἐν Χριστῷ Ἰησοῦ.

Paul makes a threefold affirmation which corresponds to a number of Jewish formulas in which the threefold distinction is maintained, as in the morning prayer in which the male Jew thanks God that he was not made a Gentile, a slave or a woman (S. Singer, The Authorised Daily Prayer Book [London, 1939], 5f.). This threefold thanksgiving can be traced back as far as R. Judah b. Elai, c. AD 150 (t. Ber. 7.18), or his contemporary R. Me'ir (b. Men. 43b)—both with 'brutish man' [bôr] instead of 'slave'. The reason for the threefold thanksgiving was not any positive disparagement of Gentiles, slaves or women as persons but the fact that they were disqualified from several religious privileges which were open to free Jewish males....It is not unlikely that Paul himself had been brought up to thank God that he was born a Jew and not a Gentile, a freeman and not a slave, a man and not a woman. If so, he takes up each of these three distinctions which had considerable importance in Judaism and affirms that in Christ they are all irrelevant.Philo, On the Life of Moses 2.18-20 (tr. F.H. Colson):

Throughout the world of Greeks and barbarians, there is practically no state which honours the institutions of any other. Indeed, they can scarcely be said to retain their own perpetually, as they adapt them to meet the vicissitudes of times and circumstances. The Athenians reject the customs and institutions of the Lacedaemonians, and the Lacedaemonians those of the Athenians; nor, in the world of the barbarians, do the Egyptians maintain the laws of the Scythians nor the Scythians those of the Egyptians—nor, to put it generally, Europeans those of Asiatics nor Asiatics those of Europeans. We may fairly say that mankind from east to west, every country and nation and state, shew aversion to foreign institutions, and think that they will enhance the respect for their own by shewing disrespect for those of other countries. It is not so with ours. They attract and win the attention of all, of barbarians, of Greeks, of dwellers on the mainland and islands, of nations of the east and the west, of Europe and Asia, of the whole inhabited world from end to end.

τῶν κατὰ τὴν Ἑλλάδα καὶ βάρβαρον, ὡς ἔπος εἰπεῖν, οὐδεμία πόλις ἐστίν, ἣ τὰ ἑτέρας νόμιμα τιμᾷ, μόλις δὲ καὶ τῶν αὑτῆς εἰς ἀεὶ περιέχεται, πρὸς τὰς τῶν καιρῶν καὶ τῶν πραγμάτων μεθαρμοζομένη τροπάς. Ἀθηναῖοι τὰ Λακεδαιμονίων ἔθη καὶ νόμιμα προβέβληνται καὶ Λακεδαιμόνιοι τὰ Ἀθηναίων· ἀλλ' οὐδὲ κατὰ τὴν βάρβαρον Αἰγύπτιοι τοὺς Σκυθῶν νόμους φυλάττουσιν ἢ Σκύθαι τοὺς Αἰγυπτίων ἢ συνελόντι φράσαι τοὺς τῶν κατ' Εὐρώπην οἱ τὴν Ἀσίαν οἰκοῦντες ἢ τοὺς τῶν Ἀσιανῶν ἐθνῶν οἱ ἐν Εὐρώπῃ· ἀλλὰ σχεδὸν οἱ ἀφ' ἡλίου ἀνιόντος ἄχρι δυομένου, πᾶσα χώρα καὶ ἔθνος καὶ πόλις, τῶν ξενικῶν νομίμων ἀλλοτριοῦνται καὶ οἴονται τὴν τῶν οἰκείων ἀποδοχήν, εἰ τὰ παρὰ τοῖς ἄλλοις ἀτιμάζοιεν, συναυξήσειν. ἀλλ' οὐχ ὧδ' ἔχει τὰ ἡμέτερα· πάντας γὰρ ἐπάγεται καὶ συνεπιστρέφει, βαρβάρους, Ἕλληνας, ἠπειρώτας, νησιώτας, ἔθνη τὰ ἑῷα, τὰ ἑσπέρια, Εὐρώπην, Ἀσίαν, ἅπασαν τὴν οἰκουμένην ἀπὸ περάτων ἐπὶ πέρατα.

Samuel Parr's Epitaph for Edward Gibbon

Robert DeMaria, Jr., "Samuel Parr's Epitaph for Johnson, His Library, and His Unwritten Biography," in

Jesse G. Swan, ed., Editing Lives: Essays in Contemporary Textual and Biographical Studies in Honor of O M Brack, Jr. (Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press, 2013), pp. 67-92 (at 75, note omitted):

Parr was never really happy with the changes he was forced to make in Johnson's epitaph. He went over the details again and again with later correspondents, most extensively perhaps with Lord Sheffield in 1797 when he was approached by the Lord to compose Gibbon's epitaph. In this case he decided to use the "lapidary" style:There is no statue of Gibbon at Fletching. Here is the epitaph in the Fletching parish church (click once or twice to enlarge): Here is a transcription in mixed case letters, lightly punctuated:What I had done for Johnson, I found after frequent & serious consideration, that I neither could attempt with so much propriety, nor perform with so much success, for Mr. Gibbon. The variety, the brilliancy, & even the peculiarity of Mr. Gibbon's character determined to adopt for him the lapidary stile, which was first introduced among the Italians by Laur. Pignoribus, Jac. Salianus, Em. Thesaurus, Oct. Fermarius, Jo. Palatius, &c. & which afterward was employed by the French, the Germans, & by our own Countrymen.The epitaph for Gibbon is on his statue at Fletching in Sussex.

Eduardus Gibbon,Here is an English translation of the epitaph, from a paper copy in the church:

criticus acri ingenio et multiplici doctrina ornatus

idemque historicorum qui fortunam

imperii Romani

vel labentis et inclinati vel eversi et funditus deleti

litteris mandaverint

omnium facile princeps,

cujus in moribus erat moderatio animi

cum liberali quadam specie conjuncta

in sermone

multae gravitati comitas suaviter adspersa,

in scriptis

copiosum, splendidum,

concinnum orbe verborum

et summo artificio distinctum

orationis genus

reconditae exquisitaeque sententiae

et in momentis rerum politicarum observandis

acuta et perspicax prudentia.

Vixit annos LVI mens(es) VII dies XXVIII.

Decessit (ante diem) XVII Cal(endas) Feb(ruarias) anno sacro

MDCCLXXXXIV

et in hoc mausoleo sepultus est

ex voluntate Johannis Domini Sheffield

qui amico bene merenti et convictori humanissimo

h(anc) tab(ulam) p(oni) c(uravit).

EDWARD GIBBONHat tip: Eric Thomson.

A critical scholar endowed with a keen intellect and varied learning

He was by far the most outstanding of all the historians who have committed to writing the fortunes of the Roman Empire as it declined, fell and was finally overthrown and destroyed.

In his personal character there was a reasonableness of mind joined with liberal sentiments.

In his conversation charm was joined agreeably to deep seriousness.

In his writings was shown an abundant, well-chosen and skilful choice of words superbly crafted.

His public utterances displayed a profound and impressive command of words. In his dealing with public affairs he displayed insight, shrewdness and wisdom.

He lived for 56 years, 7 months and 28 days and died on 16 January, in the year of our Lord 1794.

[Note: The 17th day before the calends of February is 16th January]

He was buried in this tomb by the willing assent of John, Lord Sheffield, who caused this memorial to be erected to his faithful friend and learned companion.

Unembarrassed

Thomas Mann, The Magic Mountain, chapter 4 (Hans Castorp speaking about Settembrini; tr. James E. Woods):

And what a vocabulary! He's not the least embarrassed to use words like 'virtue'—I mean, really! That word has never passed my lips once in all my life—even in Latin class we always just translated virtus as 'bravery.' It made me wince deep inside, let me tell you.

Was er für Vokabeln gebraucht! Ganz ohne sich zu genieren spricht er von ›Tugend‹ — ich bitte dich! Mein ganzes Leben lang habe ich das Wort noch nicht in den Mund genommen, und selbst in der Schule haben wir immer bloß ›Tapferkeit‹ gesagt, wenn ›virtus‹ im Buche stand. Es zog sich etwas zusammen in mir, das muß ich sagen.

Sunday, August 14, 2022

The Talkative and Frivolous

An Anthology of Sanskrit Court Poetry: Vidyākara's "Subhāṣitaratnakoṣa" translated by Daniel H.H. Ingalls (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1965 = Harvard Oriental Series, 44), p. 355 (number 1286):

The talkative and frivolous prevail,

never the good in the world's opinion.

Waves ride on the ocean's top;

pearls lie deep.

Stop

Horace, Odes 2.9.17-18 (tr. Niall Rudd):

Newer› ‹Older

Do put a stop to these unseemly lamentations.Adolf Kiessling and Richard Heinze ad loc.:

desine mollium / tandem querelarum.

desine querellarum (λῆξον ὀδυρμῶν), wie abstineto (ἀπέχου) irarum III 27, 69, regnavit (ἦρξε) populorum III 30, 12 sind kühne syntaktische Neubildungen nach griechischem Muster...