Thursday, June 30, 2022

A Magic Potion

Friedrich Nietzsche, Homer and Classical Philology, Inaugural Address, University of Basel, May 28, 1869 (tr. John McFarland Kennedy, rev. Jessica N. Berry):

It must be freely admitted that philology is to some extent borrowed from several other sciences, and is mixed together like a magic potion from the strangest liquids, metals, and bones...

Man muß nämlich ehrlich bekennen, daß die Philologie aus mehreren Wissenschaften gewissermaßen geborgt und wie ein Zaubertrank aus den fremdartigsten Säften, Metallen und Knochen zusammengebraut ist...

A Lover of the Past

C.S. Lewis, interview with Sherwood E. Wirt, in God in the Dock: Essays on Theology and Ethics, ed. Walter Hooper (1970; rpt. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2014), pp. 285-296 (at 292):

Wirt: How would you evaluate modern literary trends as exemplified by such writers as Ernest Hemingway, Samuel Beckett and Jean-Paul Sartre?Hat tip: Joel Eidsath.

Lewis: I have read very little in this field. I am not a contemporary scholar. I am not even a scholar of the past, but I am a lover of the past.

Ruins

Rutilius Namatianus, De reditu suo 1.409-414 (tr. J.Wight Duff and Arnold M. Duff):

The memorials of an earlier age cannot be recognised;

devouring time has wasted its mighty battlements away.

Traces only remain now that the walls are lost:

under a wide stretch of rubble lie the buried homes.

Let us not chafe that human frames dissolve:

from precedents we discern that towns can die.

agnosci nequeunt aevi monumenta prioris:

grandia consumpsit moenia tempus edax. 410

sola manent interceptis vestigia muris:

ruderibus latis tecta sepulta iacent.

non indignemur mortalia corpora solvi:

cernimus exemplis oppida posse mori.

Wednesday, June 29, 2022

We Have Lost Something

Lisa Jardine, Erasmus, Man of Letters: The Construction of Charisma in Print (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015), pp. 4-5:

We twentieth-century advancers of learning have altogether lost any such confidence in grand designs. We are painfully aware of an apparently flagging eminence, a diminished stature, a waning of a world in which men of letters made the agenda, and worldly men then strove to pursue it. We have ceased, I suggest, to promote learning as such, because we have lost Erasmus's conviction that true learning is the originator of all good and virtuous action—that right thought produces right government. In fact, of course, we try not to use words like true, good, virtuous, and right at all, if we can help it. They embarrass us. We are too deeply mired in the relativity of all things to risk truth claims. And on the whole we believe that in all of this, our age is one of loss—that we have lost something which the age of Erasmus possessed.

Freedom and Ease from Strife

John Swinnerton Phillimore, "Lermontov's Despair," lines 9-12, Things New and Old (Oxford: Humphrey Milford, 1918), p. 22:

No, there is naught I look for now in life,

For nothing in the past I feel regret:

Freedom is all I seek, and ease from strife.

Ah, could a man sleep soundly and forget!

Newcomers and Gangrels

J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings, Part 3: The Return of the King (VI.7: Homeward Bound; Barliman Butterbur speaking):

'No one comes nigh Bree now from Outside,' he said. 'And the inside folks, they stay at home mostly and keep their doors barred. It all comes of those newcomers and gangrels that began coming up the Greenway last year, as you may remember; but more came later. Some were just poor bodies running away from trouble; but most were bad men, full o' thievery and mischief.'

Imagine the Scene

Joshua T. Katz, "The Case for Secular American Yeshivas," Sapir: A Journal of Jewish Conversations 4 (Winter 2022):

Without philology — literally “love of words” in Greek — no one can properly follow, reproduce, or debate the merits and failings of a text.

And yet, sidelining philology is what most humanities departments have been doing for decades. All too often, professional humanists, and therefore also their students, do not so much read texts as approach them with one or another deliberate lens. They prioritize what is typically referred to as theory, believing — in large part in order not to seem irrelevant in a progressive world — that the central mission of education is not the search for truth but rather innovation, however wacky, for the sake of innovation. Textual tradition be damned.

[....]

If I sound like a cranky professor, it’s because I am one. I appreciate innovative thinking as much as the next person, but I also believe in tradition, and it is baffling to me that there are classicists who don’t.

[....]

How many people take the time to read about the hot-button issues of the day from all sides, assessing arguments and sources dispassionately rather than throwing out 280 ill-informed characters based on a sound bite or two from a single media source?

[....]

Imagine the scene: small groups of 18-year-olds sitting around a table hunched over some text or other and arguing cheerfully but with determination over the interpretation of the Second Amendment. Or the difference between the coverage of some event in the Washington Post and the Washington Examiner. Or the meaning of statesmanship, as defined by Plato, George Washington, and Barack Obama. The discussion of a given text or set of texts could go on for hours or days or weeks: There would be no formal curriculum, just a sense of doing philology, which Friedrich Nietzsche described as “slow reading.” I love this picture.

Garden Ornament

Columella, On Agriculture 10.29-34 (tr. E.S. Forster and Edward F. Heffner):

Related post: On Guard Duty.

Seek not a statue wrought by DaedalusSee Hans Herter, De Priapo (Giessen: Alfred Töpelmann, 1932 = Religionsgeschichtliche Versuche und Vorarbeiten, XXIII), p. 208.

Or Polyclitus or by Phradmon carved

Or Ageladas, but the rough-hewn trunk

Of some old tree which you may venerate

As god Priapus in your garden's midst,

Who with his mighty member scares the boys

And with his reaping-hook the plunderer.

neu tibi Daedaliae quaerantur munera dextrae,

nec Polyclitea nec Phradmonis, aut Ageladae

arte laboretur: sed truncum forte dolatum

arboris antiquae numen venerare Priapi

terribilis membri, medio qui semper in horto

inguinibus puero, praedoni falce minetur.

Related post: On Guard Duty.

Tuesday, June 28, 2022

The Fault Is Within Us

Manilius 1.904-905 (tr. G.P. Goold):

Wonder not at the grievous disasters which betide man and man's affairs, for the fault oft lies within us: we have not sense to trust heaven's message.This reminds me somewhat of Shakespeare, King Lear 1.2.116-130, although the moral is different:

ne mirere gravis rerumque hominumque ruinas,

saepe domi culpa est: nescimus credere caelo.

This is the excellent foppery of the world, that, when we are sick in fortune, often the surfeit of our own behaviour, we make guilty of our disasters the sun, the moon, and the stars; as if we were villains on necessity; fools by heavenly compulsion; knaves, thieves, and treachers by spherical pre-dominance; drunkards, liars, and adulterers by an enforc'd obedience of planetary influence; and all that we are evil in, by a divine thrusting on. An admirable evasion of whore-master man, to lay his goatish disposition to the charge of a star! My father compounded with my mother under the Dragon's Tail, and my nativity was under Ursa Major, so that it follows I am rough and lecherous. Fut! I should have been that I am, had the maidenliest star in the firmament twinkled on my bastardizing.Related post: Lack of Judgement.

Epitaph of C. Stallius Hauranus

Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum X 2971 = Carmina Latina Epigraphica 961 (from Naples; tr. Dirk Obbink):

On the inscription see Allison Catherine Boex, Hic Tacitus Lapis: Voice, Audience, and Space in Early Roman Verse-Epitaphs (diss. Cornell University, 2014), pp. 109-115, and on C. Stallius Hauranus see Kent J. Rigsby, "Hauranus the Epicurean," Classical Journal 104 (2008) 19-22.

I'm not a very clubbable man, but it wouldn't upset me to be labeled as "ex Epicureio gaudivigente choro" or "Epicuri de grege porcum" (Horace, Epist. 1.4.16).

Related post: Epitaph of an Epicurean.

Gaius Stallius Hauranus watches this place,Gaudivigens is a hapax legomenon; Franz Buecheler ad loc. says, "gaudiuigens noue fictum quasi ἡδυθαλής, animus laetitia uiget Lucr. [3.149-150]," but ἡδυθαλής is also "noue fictum," so far as I can tell. I don't have access to Thomas Lindner, Lateinische Komposita: Ein Glossar vornehmlich zum Wortschatz der Dichtersprache (Innsbruck, 1996 = Innsbrucker Beiträge zur Sprachwissenschaft, 105).

a member of the Epicurean chorus that flourishes in joy.

Stallius Gaius has sedes Hauranus tuetur,

ex Epicureio gaudivigente choro.

1 Hauranus lapis: Gauranus Hagenbuch

On the inscription see Allison Catherine Boex, Hic Tacitus Lapis: Voice, Audience, and Space in Early Roman Verse-Epitaphs (diss. Cornell University, 2014), pp. 109-115, and on C. Stallius Hauranus see Kent J. Rigsby, "Hauranus the Epicurean," Classical Journal 104 (2008) 19-22.

I'm not a very clubbable man, but it wouldn't upset me to be labeled as "ex Epicureio gaudivigente choro" or "Epicuri de grege porcum" (Horace, Epist. 1.4.16).

Related post: Epitaph of an Epicurean.

Mock-Sanskrit in Joyce's Ulysses

James Joyce, Ulysses, Episode 12 (Cyclops):

Hat tip: John O'Toole.

Questioned by his earthname as to his whereabouts in the heavenworld he stated that he was now on the path of prālāyā or return but was still submitted to trial at the hands of certain bloodthirsty entities on the lower astral levels. In reply to a question as to his first sensations in the great divide beyond he stated that previously he had seen as in a glass darkly but that those who had passed over had summit possibilities of atmic development opened up to them. Interrogated as to whether life there resembled our experience in the flesh he stated that he had heard from more favoured beings now in the spirit that their abodes were equipped with every modern home comfort such as tālāfānā, ālāvātār, hātākāldā, wātāklāsāt and that the highest adepts were steeped in waves of volupcy of the very purest nature.Pralaya (without the macrons) is a real Sanskrit word, but the others of course aren't.

Hat tip: John O'Toole.

Monday, June 27, 2022

An All-Embracing Collective

Clifford Ando, Imperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman Empire (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000), pp. 40-41 (footnote omitted):

Starting in particular with the reign of Hadrian, the imperial administration also explicitly advertised an ideology of unification. This ideology constructed the empire as an all-embracing collective by minimizing differences in culture and class and emphasizing the similarity of each individual's relationship to the emperor and especially the all-inclusive benefits of Roman rule.

Addition and Subtraction

William Morris (1834-1896), A Tale of the House of the Wolfings and All the Kindreds of the Mark (London: Reeves and Turner, 1889), p. 181 (from chapter XXIX):

[T]he host of the dead grew, and the host of the living lessened.

Imperishable Fame

Calvert Watkins (1933-2013), How to Kill a Dragon: Aspects of Indo-European Poetics (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), pp. 12-13:

Rigvedic ákṣiti śrávaḥ (1.40.4b, 8.103.5b, 9.66.7c), śrávaḥ ... ákṣitam (1.9.7bc) and Homeric κλέος ἄφθιτον (Il. 9.413) all mean 'imperishable fame'. The two phrases, Vedic and Greek, were equated by Adalbert Kuhn as early as 1853, almost en passant, in an article dealing with the nasal presents in the same two languages.1 Kuhn's innovation was a simple one, but one destined to have far-reaching consequences. Instead of making an etymological equation of two words from cognate languages, he equated two bipartite noun phrases of noun plus adjective, both meaning 'imperishable fame'. The comparability extended beyond the simple words to their suffixal constituents śrav-as- a-kṣi-ta-m, κλεϝ-ες ἀ-φθι-το-ν.2 What Kuhn had done was to equate two set or fixed phrases between two languages, which later theory would term formulas. Thus in M.L. West's somewhat lyrical words (1988a:152), 'With that famous equation of a Rig-Vedic with a Homeric formula... Kuhn in 1853 opened the door to a new path in the comparative philologist's garden of delights.' The equation has itself given given rise to a considerable literature, notably Schmitt 1967:1-102 and Nagy 1974; it is discussed at length with further references and the equation vindicated in chap. 15.The Indo-European origin of the Homeric phrase is disputed by Margalit Finkelberg, "Is κλέος ἄφθιτον a Homeric Formula?" Classical Quarterly 36 (1986) 1-5, and "More on κλέος ἄφθιτον," Classical Quarterly 57 (2007) 341–350, both reprinted in her Homer and Early Greek Epic (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2020), pp. 3-8 and 66-77. For a defence of the Indo-European origin see Katharina Volk, "κλέος ἄφθιτον Revisited," Classical Philology 97 (2002) 61–68.

1. KZ 2.467. The journal, Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Sprachforschung, was founded by Kuhn only the previous year, and for the first hundred volumes of its existence was so abbreviated, for "Kuhns Zeitschrift". With volume 101 (1988) it became Historische Sprachforschung (HS).

2. The identity of the equation could be captured by a reconstruction reducing each of the two to the same common prototype. Historically the first reconstruction in Indo-European studies, with precisely the declared aim of capturing the common prototype underlying the feminine participles Greek -ουσα and Indie -antī, had been made by August Schleicher only the year before Kuhn's article, in the preface to Schleicher 1852.

An Inescapable Fact

Eleanor Dickey, An Introduction to the Composition and Analysis of Greek Prose (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), p. x:

As necessary as memorization is consolidation. It is an inescapable fact that for most people, Greek grammatical forms and syntactic rules have a tendency to depart rapidly from the mind soon after being learned. One must simpiy accept this fact and learn the material repeatedly...

Epitaph of Asiarches

Richmond Lattimore, Themes in Greek and Latin Epitaphs (1935; rpt. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1962), p. 260:

I can't find a complete English translation of the inscription anywhere, so here is my rough version:

There remain to be considered a number of additional epitaphs which might be classed, very loosely, as philosophical.359 Tolman calls them "frivolous," and the fact is that the "philosophy" is mainly that which has for a long time passed as Epicurean; the conclusion that since life is short and death certain, the best one can do is enjoy the fun as long as it lasts. This grows from meditations on the nature of life itself, concerning which a late Roman epitaph may be cited:Lattimore cites as his source Georg Kaibel, Epigrammata Graeca ex Lapidibus Conlecta (Berlin: Reimer, 1878), p. 282, number 699, which I print here with my own critical apparatus:ἄστατος ὄντως359 Cf. Tolman 95-96; Lier (1904), 56-64.

θνητῶν ἐστι βίος καὶ βραχὺς οὐδ' ἄπονος.360

In truth the life of mortals is unsteady, short, and not without troubles.

360 EG 699, 5-6, (Rome, 3d cent. A.D.).

Νήπιον, ὠκύμορον κατέχω χθών, ὦ ξένε, παῖδα,Other editions include L. Moretti, Inscriptiones Graecae Urbis Romae III 1162 (unavailable to me), Inscriptiones Graecae XIV 1422, and Werner Peek, Griechische Vers-Inschriften (Berlin, 1955), p. 212, number 789.

ζώσαντ' ἐν μελάθροις ἐς λυκάβαντα τέταρτον.

οὔνομα δ' ἐν τοκέεσσι φίλοις κέκλητ' Ἀσιάρχης·

αὐτοὶ δ' οἳ θρέψαν τήνδ' ἐπέθοντο κόνιν

καὶ δακρύοισιν ἔβρεξαν ὅλον τάφον· ἄστατος ὄντως 5

θνητῶν ἐστι βίος καὶ βραχὺς οὐδ' ἄπονος.

versus 2 metro claudicat: μέχρις vel ὡς ante ἐς add. dub. Peek; λυκάβαντα lapis: λυκάβαν Wilhelm; τέταρτον lapis: τρίτον dub. Kaibel

I can't find a complete English translation of the inscription anywhere, so here is my rough version:

I, the earth, cover a prematurely dead infant child, o stranger,There is a Spanish translation in María Luisa del Barrio Vega, Epigramas funerarios griegos (Madrid: Editorial Gredos, 1992), p. 174:

who lived in his house up to his fourth year.

By name he was called Asiarches by his dear parents;

they who raised him buried these ashes

and drenched the whole tomb with their tears; unsteady in truth

is the life of mortals, and short, and not without troubles.

Yo soy la tierra que guarda a un niño de corta edad, de prematura muerte, extranjero: cuatro años fueron los que vivió en su casa. Asiarques era el nombre con el que lo llamaban sus padres. Este polvo esparcieron quienes lo criaron, y con sus lágrimas han humedecido toda su tumba. Fugaz es, en verdad, la vida de los mortales, breve y llena de pesares.

Sunday, June 26, 2022

Dislike of Travel

Eleanor Dickey, "J.N. Adams (1943-2021)," Commentaria Classica 8 (2021) 225-228 (at 227):

Born in Sydney, Australia, in 1943, Adams graduated from the University of Sydney in 1965 and in 1967 flew to England to embark on doctoral work at Oxford. He found the flying so traumatic that he could never get on an aeroplane again and remained in Britain for the rest of his life, though he always considered himself emphatically Australian. Adams' dislike of travel was not confined to flying: he almost never crossed the Channel by any means, and even within the UK rarely attended conferences. He thereby gained much more time for writing, and he ran no risk of being sidelined from contemporary scholarly discourse: the world's Latinists flocked to consult him individually, both about his ideas and about their own.

We May No Longer Endure These Outlanders

William Morris (1834-1896), A Tale of the House of the Wolfings and All the Kindreds of the Mark (London: Reeves and Turner, 1889), p. 154 (from chapter XXV):

But now look to it what ye will do; for we may no longer endure these outlanders in our houses, and we must either die or get our own again: and that is not merely a few wares stored up for use, nor a few head of neat, nor certain timbers piled up into a dwelling, but the life we have made in the land we have made. I show you no choice, for no choice there is.

Attentive Reading

John Ruskin (1819-1900), Sesame and Lilies, rev. ed. (London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1871), p. 17:

[Y]ou must get into the habit of looking intensely at words, and assuring yourself of their meaning, syllable by syllable—nay, letter by letter.Related posts:

The Founders of the Modern Spirit

Ernest Renan (1823-1892) The Future of Science (London: Chapman and Hall, Limited, 1891), p. 131:

The modern spirit, that is, rationalism, criticism, liberalism, was founded on the same day that philology was founded. The founders of the modern spirit are the philologists.

L'esprit moderne, c'est-à-dire le rationalisme, la critique, le libéralisme, a été fondé le même jour que la philologie. Les fondateurs de l'esprit moderne sont des philologues.

Saturday, June 25, 2022

Accidents Happen

Joshua T. Katz, "The Muse at Play: An Introduction," in Jan Kwapisz et al., edd., The Muse at Play: Riddles and Wordplay in Greek and Latin Poetry (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2013), pp. 1-30 (at 5, footnote omitted):

Acrostics are seemingly straightforward, but the existence of C-A-C-A-T-A ("shitty") in Eclogue 4.47–52 will suffice to show that accidents happen.

I'm Vexed and Grieved

Aristophanes, Assemblywomen 174-179 (tr. Stephen Halliwell):

I'm vexed and grieved to seeR.G. Ussher ad loc.:

The poor condition the city's affairs are in.

I notice how she always has as leaders

The rotten types. If one of them is decent

For one whole day, he's rotten then for ten!

If you switch to another, he'll only make things worse.

ἄχθομαι δὲ καὶ φέρω

τὰ τῆς πόλεως ἅπαντα βαρέως πράγματα. 175

ὁρῶ γὰρ αὐτὴν προστάταισι χρωμένην

ἀεὶ πονηροῖς. κἄν τις ἡμέραν μίαν

χρηστὸς γένηται, δέκα πονηρὸς γίγνεται.

ἐπέτρεψας ἑτέρῳ· πλείον᾿ ἔτι δράσει κακά.

175 ἅπαντα codd.: σαπέντα Palmer: παρόντα Jackson

Masked Words

John Ruskin, Sesame and Lilies, rev. ed. (London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1871), pp. 19-20:

There are masked words droning and skulking about us in Europe just now, — (there never were so many, owing to the spread of a shallow, blotching, blundering, infectious "information," or rather deformation, everywhere, and to the teaching of catechisms and phrases at school instead of human meanings) — there are masked words abroad, I say, which nobody understands, but which everybody uses, and most people will also fight for, live for, or even die for, fancying they mean this or that, or the other, of things dear to them: for such words wear chameleon cloaks — "ground-lion" cloaks, of the colour of the ground of any man's fancy: on that ground they lie in wait, and rend them with a spring from it. There never were creatures of prey so mischievous, never diplomatists so cunning, never poisoners so deadly, as these masked words; they are the unjust stewards of all men's ideas: whatever fancy or favourite instinct a man most cherishes, he gives to his favourite masked word to take care of for him; the word at last comes to have an infinite power over him, — you cannot get at him but by its ministry.Chameleon comes from χαμαί (on the ground) and λέων (lion).

The Mad Impulse of One Mind

Jordanes, Gothic History 36.193 (tr. Charles Christopher Mierow):

What just cause can be found for the encounter of so many nations, or what hatred inspired them all to take arms against each other? It is proof that the human race lives for its kings, for it is at the mad impulse of one mind a slaughter of nations takes place, and at the whim of a haughty ruler that which nature has taken ages to produce perishes in a moment.Related post: The King and His Subjects.

quae potest digna causa tantorum motibus invenire? aut quod odium in se cunctos animavit armari? probatum est humanum genus regibus vivere, quando unius mentis insano impetu strages sit facta populorum et arbitrio superbi regis momento defecit quod tot saeculis natura progenuit.

Friday, June 24, 2022

For You Too

Inscriptiones Graecae I2 972, tr.

Paul Friedländer and Herbert B. Hoffleit, Epigrammata: Greek Inscriptions in Verse from the Beginnings to the Persian Wars (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1948), p. 88:

Before the tomb of brave and wise Antilochus

[shed a tear]; for you too death awaits.

Aristion made me.

Ἀ]ντιλόχου ποτὶ σῆμ' ἀγαθοῦ καὶ σόφρονος ἀνδρὸς

[δάκρυ κ]άταρ[χ]σον̣, [ἐ]π[ε]ὶ καὶ σὲ μένει θάνατος.

Ἀριστίον μ' ἐπόησεν.

Reverence for the Text

H. Craig Melchert, "In Memoriam

Calvert Watkins," Journal of Indo-European Studies 41.3/4 (Fall/Winter 2013) 506-526 (at 510-511):

With his gift for large-scale synthesis and willingness to explore novel approaches, Calvert Watkins nevertheless firmly believed that "the devil is in the details." All of his linguistic analyses and hypotheses, from the most modest individual word etymology to his grandest and boldest reconstructed schemata rested on rock-solid philological foundations—and he insisted that his students' analyses did likewise. Originality without proper grounding veers easily into unbridled fantasy, and generalizations become self-perpetuating dogma. In Watkins' work an unwavering "reverence for the text" forestalled any such tendencies. He viewed recalcitrant facts that did not fit an analysis not as inconveniences to be ignored, but as priceless clues to a better solution—something to which he hoped his students would contribute.Related post: The Courage to Make a Mistake.

Blacksmith Working on a Helmet

Attic red-figure stemmed cup depicting a blacksmith working on a helmet, attributed to the Antiphon Painter, ca. 480 B.C. (Oxford, Ashmolean Museum, accession number AN1896-1908.G.267):

John H. Oakley, A Guide to Scenes of Daily Life on Athenian Vases (Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2020), pp. 51-52:

Second in popularity on Athenian vases, after the images connected with pottery production, were scenes of metalworkers. Interestingly, a major metalworking area of Athens was in the northwest Agora and not far from the Kerameikos, the potters' quarters, so that the painters did not have far to look for inspiration. Several of the metalworking scenes are mythological, showing Thetis and/or Hephaistos or Athena, and occasionally satyrs, so they are not included here. Armor is the most common object being worked on by the smiths, with a helmet, as in the tondo of a red-figure cup in Oxford by the Antiphon Painter of 480 BC (fig. 2.5), being the most popular object. Seated on a diphros, the smith holds out a Corinthian helmet in his left hand and a file/rasp in his right. Other tools, five files/rasps of different sizes, hang above him in the background; a furnace stands behind him and an anvil, an akmotheton, is set in a mound before him. On other vases, greaves, tripods, statues, and swords are shown being worked on.

Skill

Bernard DeVoto (1897-1955), Across The Wide Missouri (1947; rpt. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1964), pp. 158-160:

Skill develops from controlled, corrected repetitions of an act for which one has some knack. Skill is a product of experience and criticism and intelligence. Analysis cannot much transcend those truisms. Between the amateur and the professional, between the duffer and the expert, between the novice and the veteran there is a difference not only in degree but in kind. The skillful man is, within the function of his skill, a different integration, a different nervous and muscular and psychological organization. He has specialized responses of great intricacy. His associative faculties have patterns of screening, acceptance and rejection, analysis and sifting, evaluation and selective adjustment much too complex for conscious direction. Yet as the patterns of appraisal and adjustment exert their automatic and perhaps metabolic energy, they are accompanied by a conscious process fully as complex. A tennis player or a watchmaker or an airplane pilot is an automatism but he is also criticism and wisdom.

It is hardly too much to say that a mountain man's life was skill. He not only worked in the wilderness, he also lived there and he did so from sun to sun by the exercise of total skill. It was probably as intricate a skill as any ever developed by any way of working or living anywhere. Certainly it was the most complex of the wilderness crafts practiced on this continent. The mountains, the aridity, the distances, and the climates imposed severities far greater than those laid on forest-runners, rivermen, or any other of our symbolic pioneers. Mountain craft developed out of the crafts which earlier pioneers had acquired and, like its predecessors, incorporated Indian crafts, but it had a unique integration of its own. It had specific crafts, technologies, theorems and rationales and rules of thumb, codes of operating procedure — but it was a pattern of total behavior.

Treatises could be written on the specific details; we lack space even for generalizations. Why do you follow the ridges into or out of unfamiliar country? What do you do for a companion who has collapsed from want of water while crossing a desert? How do you get meat when you find yourself without gunpowder in a country barren of game? What tribe of Indians made this trail, how many were in the band, what errand were they on, were they going to or coming back from it, how far from home were they, were their horses laden, how many horses did they have and why, how many squaws accompanied them, what mood were they in? Also, how old is the trail, where are those Indians now, and what does the product of these answers require of you? Prodigies of such sign-reading are recorded by impressed greenhorns, travelers, and army men, and the exercise of critical reference and deduction which they exhibit would seem prodigious if it were not routine. But reading formal sign, however impressive to Doctor Watson or Captain Fremont, is less impressive than the interpretation of observed circumstances too minute to be called sign. A branch floats down a stream — is this natural, or the work of animals, or of Indians or trappers? Another branch or a bush or even a pebble is out of place — why? On the limits of the plain, blurred by heat mirage, or against the gloom of distant cottonwoods, or across an angle of sky between branches or where hill and mountain meet, there is a tenth of a second of what may have been movement — did men or animals make it, and, if animals, why? Buffalo are moving downwind, an elk is in an unlikely place or posture, too many magpies are hollering, a wolf's howl is off key — what does it mean?

Such minutiae could be extended indefinitely. As the trapper's mind is dealing with them, it is simultaneously performing a still more complex judgment on the countryside, the route across it, and the weather. It is recording the immediate details in relation to the remembered and the forecast. A ten-mile traverse is in relation to a goal a hundred miles, or five hundred miles, away: there are economies of time, effort, comfort, and horseflesh on any of which success or even survival may depend. Modify the reading further, in relation to season, to Indians, to what has happened. Modify it again in relation to stream flow, storms past, storms indicated. Again in relation to the meat supply. To the state of the grass. To the equipment on hand. . . . You are two thousand miles from depots of supply and from help in time of trouble.

All this (with much more) is a continuous reference and checking along the margin or in the background of the trapper's consciousness while he practices his crafts as hunter, wrangler, furrier, freighter, tanner, cordwainer, smith, gunmaker, dowser, merchant. The result is a high-level integration of faculties. The mountain man had mastered his conditions — how well is apparent as soon as soldiers, goldseekers, or emigrants come into his country and suffer where he has lived comfortably and die where he has been in no danger. He had no faculties or intelligence that the soldier or the goldseeker lacked; he had none that you and I lack. He had only skill.

Thursday, June 23, 2022

Retirement

Aristophanes, Assemblywomen 464 (tr. Jeffrey Henderson):

You can stop groaning and stay at home farting all day.

σὺ δ᾽ ἀστενακτὶ περδόμενος οἴκοι μενεῖς.

Labels: noctes scatologicae

A Fair City

J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings, Part 3: The Return of the King (VI.5: The Steward and the King):

In his time the City was made more fair than it had ever been, even in the days of its first glory; and it was filled with trees and with fountains, and its gates were wrought of mithril and steel, and its streets were paved with white marble; and the Folk of the Mountain laboured in it, and the Folk of the Wood rejoiced to come there; and all was healed and made good, and the houses were filled with men and women and the laughter of children, and no window was blind nor any courtyard empty; and after the ending of the Third Age of the world into the new age it preserved the memory and the glory of the years that were gone.

New Poetry Anthology

"GCSE removes Wilfred Owen and Larkin in diversity push," The Times (June 23, 2022):

Hat tip: Eric Thomson, who remarks, "'All that will survive of us is love'. If there's much more of this sort of craven pandering, nothing will survive of me but a puddle of bile."

"What will survive of us is love," Philip Larkin wrote in An Arundel Tomb.GCSE = General Certificate of Secondary Education; OCR = Oxford, Cambridge and Royal Society of Arts

Neither the poem nor the poet, however, has survived a shake-up of works included in a GCSE poetry anthology.

OCR, one of the three main exam boards, has removed works by John Keats, Thomas Hardy, Wilfred Owen and Larkin from its English literature syllabus from this September.

Some poems by Hardy and Keats will remain, but there will be no poetry by Larkin, Seamus Heaney or Owen, whose Anthem for Doomed Youth is on the present syllabus.

The "conflict" section of the anthology contains none of the best known First World War poets, such as Siegfried Sassoon, Rupert Brooke and Robert Graves. Instead, it has new works including We Lived Happily during the War by Ilya Kaminsky, Colonization in Reverse by Louise Bennett Coverly [sic, read Coverley] and Thirteen by Caleb Femi. OCR said 15 new poems were included, 30 retained and 15 removed. The syllabus will be used in exams in the summer of 2024.

The exam board described the new poems as "exciting and diverse", adding: "Our anthology for GCSE English literature students will feature many poets that have never been on a GCSE syllabus before and represent diverse voices, from living poets of British-Somali, British-Guyanese and Ukrainian heritage to one of the first black women in 19th century America to publish a novel. Of the 15 poets whose work has been added, 14 are poets of colour. Six are black women, one is of South Asian heritage. Our new poets also include disabled and LGBTQ+ voices."

The anthology has three themes: love and relationships, conflict, and youth and age. It also retains works by William Blake, Emily Brontë, Sylvia Plath and Carol Ann Duffy and adds the British-Jamaican poet Raymond Antrobus, 36, and Kaminsky, 45, a Ukrainian-American who is deaf.

Works by the British-Somali poet Warsan Shire, 33, and British-Nigerian poet Theresa Lola, 28 — both young people's laureates for London — illustrate the theme of "youth and age".

Judith Palmer, director of the Poetry Society, said: "It's fantastic to see this new selection including poets from such a range of backgrounds and identities, writing in such diverse forms, voices and styles."

Hat tip: Eric Thomson, who remarks, "'All that will survive of us is love'. If there's much more of this sort of craven pandering, nothing will survive of me but a puddle of bile."

Evils of the Machine Age

G.M. Trevelyan, "Macaulay and the Sense of Optimism," in Ideas and Beliefs of the Victorians: An Historic Revaluation of the Victorian Age (1949; rpt. London: Sylvan Press, 1950), pp. 46-52 (at 50-51):

Macaulay was not wrong in thinking that the English were better off materially, and were certainly more humane than in the past. The facts that escaped his notice, and escaped the notice of most of his contemporaries, were other evils that the machine age had brought—the destruction of craftsmanship and the intelligent joy of man in his daily work, the ugliness and depressing aspect of the great new cities which were taking the place of farm, village and country town as the scene of ordinary human existence; the loss of rural tradition, which had been the real basis of our higher civilisation in England from the days of Chaucer and Shakespeare onwards.

Credible Evidence

Jordanes, Gothic History 5.38 (tr. Charles Christopher Mierow):

For myself, I prefer to believe what I have read, rather than put trust in old wives' tales.

nos enim potius lectioni credimus quam fabulis anilibus consentimus.

Wednesday, June 22, 2022

Doktorvater

Joshua Katz, "The Educational Guild," Daily Princetonian (April 2, 2013):

No one needs me to explain that, thanks to nature and nurture, all of us inherit and take on traits, good and bad, from our parents. But there are academic parents, too, and their influence, which can naturally have a profound effect on any student, is typically of particular importance to those of us who choose to follow seriously in their intellectual footsteps and join the educational guild ourselves.Joshua Katz wrote 36 articles for the Daily Princetonian. I have been able to find only two on the World Wide Web, this one and My Two Ferdinands. Considering the current frenzy in favor of cancellation, I downloaded them, because I don't know how much longer they will survive in cyberspace.

I was astonishingly fortunate in my teachers, both in college and in graduate school, and it would be wrong of me to name any one of them as my most important influence: I study what I study, teach what I teach and in many ways am what I am because I am a mutt, the son of all of them. Nevertheless, when one's Doktorvater — that wonderful German word for Ph.D. supervisor, literally "doctor-father" — is the single most prominent scholar in the field, and when that scholar is also a deeply kind person who has no truck with hierarchy, it would be wrong to downplay the extraordinary role he has had in shaping one's career. And that's the case with me: My Doktorvater was Calvert Watkins, the leading historical and comparative linguist and Indo-Europeanist of our times ...

[....]

But it isn't because of his brilliance that I loved Calvert. I loved him because he had a fantastic sense of humor, because he was the consummate host, because he had a thing about black-eyed peas, because he introduced me to Myers's Rum with a splash of tonic and a wedge of lime, because he devoured mysteries, because he wasn't pretentious and yet wore a pocket watch and because he really and truly couldn't understand how anyone could claim to be educated without being able to read cuneiform. During my years as a graduate student, few days passed when I didn't have at least one formal or informal class with him, few days when we didn't have at least one informal meal or drink together. In and out of the classroom, day after day, he taught simply by being himself.

[....]

The pursuit and advancement of knowledge is a traditional craft, in some ways not unlike blacksmithing and the production of stained glass, and giving a lecture of this kind is a neat way of demonstrating to students that they are part of a tradition.

Arminius

Statue of Arminius in New Ulm, Minnesota (click once or twice to enlarge):

Thanks to Mrs. Laudator for taking the photographs.

Related posts:

Related posts:

So Fares Hot Blood

William Morris (1834-1896), A Tale of the House of the Wolfings and All the Kindreds of the Mark (London: Reeves and Turner, 1889), p. 144 (from chapter XXIII):

So fares hot blood to the glooming and the world beneath the grass;

And the fruit of the Wolfings' orchard in a flash from the world must pass.

Men say that the tree shall blossom in the garden of the folk,

And the new twig thrust him forward from the place where the old one broke,

And all be well as aforetime: but old and old I grow,

And I doubt me if such another the folk to come shall know.

Epitaph of Arcadion

Epitaph of Arcadion, preserved by Athenaeus 10.436d = Werner Peek, Griechische Vers-Inschriften, Vol. I: Grab-Epigramme (Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 1955), p. 58, # 221 (tr. S. Douglas Olson):

This tomb, which belongs to Arcadion of the many cups,See Francis Cairns, Hellenistic Epigram: Contexts of Exploration (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), pp. 254-255.

was erected here beside the path that leads to the city

by his sons Dorcon and Charmylus. The man died,

sir, by gulping down six cups of strong wine.

τοῦ πολυκώθωνος τοῦτ' ἠρίον Ἀρκαδίωνος

ἄστεος ὤρθωσαν τᾷδε παρ' ἀτραπιτῷ

υἱῆες Δόρκων καὶ Χαρμύλος· ἔφθιτο δ' ὡνήρ,

ὤνθρωπ', ἓκ χανδῆς ζωροποτῶν κύλικας.

4 ἐκ χανδῆς codd.: ἓκ χανδὸν Dilthey: εὐχανδεῖς Lobeck

Tuesday, June 21, 2022

Fatalism

"Fatalism," from the Hitopadesha, tr. Arthur William Ryder, Relatives, Being Further Verses Translated from the Sanskrit (San Francisco: A.M. Robertson, 1919), p. 70:

What shall not be, will never be;The same, tr. Edwin Arnold, The Book of Good Counsels, from the Sanskrit of the 'Hitopadeśa' (London: W.H. Allen and Co., Limited, 1893), p. 18:

What shall be, will be so:

This tonic slays anxiety;

Taste it, and end your woe.

That which will not be, will not be — and what is to be, will be: Why not drink this easy physic, antidote of misery?

For Virile Power

Calvert Watkins, "The Third Donkey: Origin Legends and Some Hidden Indo-European Themes," in J.H.W. Penney, ed., Indo-European Perspectives: Studies in Honour of Anna Morpurgo Davies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), pp. 65-80, rpt. in his Selected Writings, ed. Lisi Oliver, Vol. III: Publications 1992-2008 (Innsbruck: Institut für Sprachwissenschaft der Universität Innsbruck, 2008 = Innsbrucker Beiträge zur Sprachwissenschaft, 129), pp. 1033-1048 (at 1035-1036):

I'm too lazy to transcribe this, because of all the diacritics. If you substitute my for thy, this could be a personal prayer. I hope it works for you.

Glory

Homer, Odyssey 8.147-148 (tr. Richmond Lattimore):

For there is no greater glory that can befall a man livingNeither speed nor strength is in the Greek. The same (tr. A.T. Murray):

than what he achieves by speed of his feet or strength of his hands.

οὐ μὲν γὰρ μεῖζον κλέος ἀνέρος ὄφρα κ᾽ ἔῃσιν,

ἤ ὅ τι ποσσίν τε ῥέξῃ καὶ χερσὶν ἑῇσιν.

For there is no greater glory for a man so long as he lives than that which he achieves by his own hands and his feet.W.B. Stanford ad loc.:

147-8 are lines worth memorizing as an expression of the Greeks' intense love and admiration of athletics, as illustrated also in the Victory Odes of Pindar and the athletic sculptures of the fifth century.

Monday, June 20, 2022

Epicurean Advice

Corpus Inscriptionum Graecarum III 3846.L (Aizanoi, Phrygia) = Philippe Le Bas, Voyage archéologique en Grèce et en Asie Mineure fait pendant les années 1843 et 1844, Tome III, Première Partie: Inscriptions (Paris: Didot, 1870), p. 266, number 977 (my translation):

"Down here" means in the grave. I take Anthos to be a personal name, rather than "a flower". See e.g. T. Corsten, ed., A Lexicon of Greek Personal Names, Vol. V.A: Coastal Asia Minor: Pontos to Ionia (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2010), p. 34. Franz Cumont, "Une pierre tombale érotique de Rome," L'Antiquité Classique 9 (1940) 5–11 (at 8), also regards it as a proper name, but Andrzej Wypustek, "Laughing in the Face of Death: a Survey of Unconventional Hellenistic and Greek-Roman Funerary Verse-Inscriptions," Klio 103 (2021) 160-187 (at 174), translates it (wrongly, in my view) as "the flower".

Anthos to the passersby: greetings! Bathe, drink, eat, copulate. For down here you have none of these things.The Packard Humanities Institute's Searchable Greek Inscriptions lists the source as C.W.M. Cox et al., Monumenta Asiae Minoris Antiqua, Vol. IX: Monuments from the Aezanitis (London: Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies, 1988 = Journal of Roman Studies Monographs, 4), p. 189 (number P300), which is next to worthless, since MAMA IX doesn't print the Greek and merely refers to the publications listed above.

Ἄνθος τοῖς παροδείταις χαίριν· λοῦσαι, πίε, φαγὲ, βείνησον· τούτων γὰρ ὧδε κάτω [οὐ]δὲ<ν> ἔχις.

"Down here" means in the grave. I take Anthos to be a personal name, rather than "a flower". See e.g. T. Corsten, ed., A Lexicon of Greek Personal Names, Vol. V.A: Coastal Asia Minor: Pontos to Ionia (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2010), p. 34. Franz Cumont, "Une pierre tombale érotique de Rome," L'Antiquité Classique 9 (1940) 5–11 (at 8), also regards it as a proper name, but Andrzej Wypustek, "Laughing in the Face of Death: a Survey of Unconventional Hellenistic and Greek-Roman Funerary Verse-Inscriptions," Klio 103 (2021) 160-187 (at 174), translates it (wrongly, in my view) as "the flower".

A Hard Student

Thomas Jefferson, letter to Vine Utley (March 21, 1819):

I was a hard student until I entered on the business of life, the duties of which leave no idle time to those disposed to fulfill them; & now, retired, and at the age of 76, I am again a hard student.

Pindar

Calvert Watkins, "ΕΠΕΩΝ ΘΕΣΙΣ. Poetic Grammar: Word Order and Metrical Structure in the Odes of Pindar," in Heinrich Hettrich, ed., Indogermanische Syntax: Fragen und Perspektiven (Wiesbaden: Reichert, 2002), pp. 319–337, rpt. in his Selected Writings, ed. Lisi Oliver, Vol. III: Publications 1992-2008 (Innsbruck: Institut für Sprachwissenschaft der Universität Innsbruck, 2008 = Innsbrucker Beiträge zur Sprachwissenschaft, 129), pp. 1005-1023 (at 1005):

If I may quote a recent personal communication from the Regius Professor, Peter Parsons of Christ Church, Oxford: "The very word Pindar — as I know from teaching him — turns otherwise muscular colleagues to jelly."Related posts:

Sunday, June 19, 2022

Some European Personal Names

Calvert Watkins, "Two Celtic Notes," in Peter Anreiter and Erzsébet Jerem, edd., Studia Celtica et Indogermanica: Festschrift für Wolfgang Meid zum 70. Geburtstag (Budapest: Archaeolingua Alapítvány, 1999), pp. 539-543, rpt. in his Selected Writings, ed. Lisi Oliver, Vol. III: Publications 1992-2008 (Innsbruck: Institut für Sprachwissenschaft der Universität Innsbruck, 2008 = Innsbrucker Beiträge zur Sprachwissenschaft, 129), pp. 916-920 (at 919, on the etymology of Gaulish buððutton):

[T]he number of European personal names like Mentula, Couillard, Schwanz, Schmuck, perhaps Gvozdanović and quite possibly Wacker-nagel would suggest the male organ as a likelier onomastic etymon than 'kiss.'Related post: Squeamishness.

Life

Bhartrihari, "Life," tr. Arthur William Ryder, Relatives, Being Further Verses Translated from the Sanskrit (San Francisco: A.M. Robertson, 1919), p. 44:

Here is the sound of lutes, and there are screams and wailings;

Here winsome girls, there bodies old and failing;

Here scholars' talk, there drunkards' mad commotion—

Is life a nectared or a poisoned potion?

Alii Alia

Egil Kraggerud, Critica: Textual Issues in Horace, Ennius, Vergil and Other Authors (Abingdon: Routledge, 2020), p. 21:

An annoying trait that seems to persist among industrious compilers should be banned once and for all; that is the habit, usually prompted by fatigue I believe, of adding an alii alia or the like to two or three proposals mentioned, sometimes no doubt more or less by chance.

Swords into Plowshares, Spears into Pruning Hooks

Claudian, Against Eutropius 2.194-196 (tr. Maurice Platnauer):

Go then, busy thyself with the plough, cleave the soil, bid thy followers lay aside their swords and sweat o'er the harrow.

i nunc, devotus aratris

scinde solum positoque tuos mucrone sodales

ad rastros sudare doce.

Frugality

Thomas Jefferson, letter to Elbridge Gerry (January 26, 1799):

I am for a government rigorously frugal & simple, applying all the possible savings of the public revenue to the discharge of the national debt; and not for a multiplication of officers & salaries merely to make partisans, & for increasing, by every device, the public debt, on the principle of it's being a public blessing.

Saturday, June 18, 2022

Minding Other People's Business

Bertolt Brecht, Mann ist Mann, Scene 4 (tr. Gerhard Nellhaus):

There are some people who will keep sticking their noses into everything. Give them a finger and they'll have your whole hand.Related posts:

Es gibt Leute, die ihre Nase in gar alle Angelegenheiten hineinstecken müssen. Wenn man solchen Leuten den kleinen Finger reicht, nehmen sie gleich die ganze Hand.

- Let's Stop Somebody from Doing Something!

- Foolish

- Right Thinkers

- Against Busybodies and Nosey Parkers

- Recipe for a Happy Life

Silver Stag Vessels

Silver stag vessel, Central Anatolia, ca. 14th–13th century B.C., in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (acc. no. 1989.281.10, gift of the Norbert Schimmel Trust):

See Theo van den Hout, "The Silver Stag Vessel: A Royal Gift," Metropolitan Museum Journal 53 (2018) 114-127.

Silver stag vessel found in Mycenae, Grave Circle A, Grave IV, ca. 16th century B.C., in Athens, National Archaeological Museum (inv. no. 388): See Robert B. Koehl, "The Silver Stag 'Bibru' from Mycenae," in Jane B. Carter and Sarah P. Morris, edd., The Ages of Homer: A Tribute to Emily Townsend Vermeule (Austin: The University of Texas Press, 2014), pp. 61-66.

Silver stag vessel found in Mycenae, Grave Circle A, Grave IV, ca. 16th century B.C., in Athens, National Archaeological Museum (inv. no. 388): See Robert B. Koehl, "The Silver Stag 'Bibru' from Mycenae," in Jane B. Carter and Sarah P. Morris, edd., The Ages of Homer: A Tribute to Emily Townsend Vermeule (Austin: The University of Texas Press, 2014), pp. 61-66.

An Awful Tigress

Bhartrihari, "Heedlessness," tr. Arthur William Ryder, Relatives, Being Further Verses Translated from the Sanskrit (San Francisco: A.M. Robertson, 1919), p. 6:

Old age, an awful tigress, growls:The same, tr. B. Hale Wortham, The Śatakas of Bhartṛihari (1886; rpt. Abingdon: Routledge, 2000), p. 55:

And shafts of sickness pierce the bowels;

Life's water trickles from its jar—

'Tis strange how thoughtless people are.

Old age menaces the body like a tiger; diseases carry it off like enemies; life slips away like water out of a broken jar; and yet man lives an evil life in the world. Truly this is marvellous.

Friday, June 17, 2022

The Sweet Luxury of Being Taught

Ray Monk, Robert Oppenheimer: A Life Inside the Center (New York: Anchor Books, 2014), pp. 204-205:

Oppenheimer's concern with truth, goodness, and beauty led him in the early 1930s to a serious study of ancient Hindu literature; so serious, indeed, that he took lessons in Sanskrit so that he could read the Hindu texts in their original language. The first mention of this comes in his letter to Frank of August 10, 1931, in which he writes, "I am learning Sanskrit, enjoying it very much, and enjoying again the sweet luxury of being taught."Id., pp.455-456:

His teacher was Arthur Ryder, who was professor of Sanskrit at Berkeley. Harold Cherniss has described Ryder as "a friend half divine in his great humanity." In his views on education, he was a curious mixture of the ultra-traditionalist and the iconclast. He believed on the one hand that a university education ought to consist primarily of Latin, Greek, and mathematics (with the other sciences and humanities given as a reward to good students and the social sciences ignored altogether). On the other hand, his approach to the teaching of Sanskrit was refreshingly free from the deadening hand of dry scholarship. He regarded the learning of Sanskrit as the opening of a door onto great literature, not as an academic discipline. Perhaps for that reason he was the ideal teacher for Oppenheimer, who held him in enormously high regard. "Ryder felt and thought and talked as a stoic," Oppenheimer once told a journalist, extolling him as "a special subclass of the people who have a tragic sense of life, in that they attribute to human actions the completely decisive role in the difference between salvation and damnation. Ryder knew that a man could commit irretrievable error, and that in the face of this fact, all others were secondary."

Because of its use in this context (recollections of the Trinity atomic tests) by Oppenheimer, "Now that I am become death, the destroyer of worlds" has become one of the best-known lines from the Bhagavad Gita. Those who go looking for those words, however, often fail to find them, since in most English translations of the text they do not appear. The Sanskrit word that Oppenheimer translates as "death" is more usually rendered as "time," so that, for example, in the Penguin Classics edition, the line is given as: "I am all-powerful Time, which destroys all things." In the famous translation by the nineteenth-century poet Edwin Arnold it appears as: "Thou seest Me as Time, who kills, Time who brings all to doom, The Slayer Time, Ancient of Days, come hither to consume," which conveys an image diametrically opposed to that of a sudden release of deadly power. Oppenheimer, however, was following the example of his Sanskrit teacher, Arthur Ryder, whose translation reads: "Death am I, and my present task destruction."Id., pp. 675-676:

Soon after he arrived back in Princeton, Oppenheimer received a letter dated February 1 from The Christian Century, a nondenominational magazine, asking him to "jot down — almost on impulse" a list of up to ten books "that most shaped your attitudes in your vocations and philosophy of life." The list he sent them was as follows:Hat tip: Jim K., old and dear friend, with whom I've shared the six things (Panchatantra, tr. Arthur Ryder):

1. Les Fleurs du mal

2. Bhagavad Gita

3. Riemann's Gesammelte mathematische Werke

4. Theaetetus

5. L'Education sentimentale

6. Divina Commedia

7. Bhartrihari's Three Hundred Poems

8. "The Waste Land"

9. Faraday's notebooks

10. Hamlet

Six things are done by friends:

To take, and give again;

To listen, and to talk;

To dine, to entertain.

Faction Within Faction

Josephus, Jewish War 5.1.4 (tr. H. St. J. Thackeray):

This new development might be not inaccurately described as a faction bred within a faction, which like some raving beast for lack of other food at length preyed upon its own flesh.

ταύτην δ᾽ οὐκ ἂν ἁμάρτοι τις εἰπὼν στάσει στάσιν ἐγγενέσθαι, καὶ καθάπερ θηρίον λυσσῆσαν ἐνδείᾳ τῶν ἔξωθεν ἐπὶ τὰς ἰδίας ἤδη σάρκας ὁρμᾷ.

An Inscription on a Greek Vase

Attic red-figure kylix by Phintias, about 510 B.C. (Malibu, Getty Museum, 80.AE.31):

From the Getty Museum web site:

Also from the Getty Museum web site:

Leslie Threatte (1943-2021), The Grammar of Attic Inscriptions, II: Morphology (Berlin: de Gruyter, 1996), p. 641: In other words, if Threatte's reading is adopted, the youth is saying ἥδομαι (I'm enjoying myself).

This inscription isn't listed in Henry R. Immerwahr, Corpus of Attic Vase Inscriptions, where the vase is mentioned under number 4943.

At the top, an inscription, E [...] A I E Λ O, perhaps uttered by the youth (whose lips are parted and who gestures with his right hand).To me it looks like he's gesturing with his left hand.

Also from the Getty Museum web site:

On B Ε[.]ΑΙΕΛΟ The letters are not easily recognisable, as the color has flaked off.The vase is apparently 1620.12 bis in J.D. Beazley, Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters, 2nd ed. (Oxford, 1963), which is unavailable to me.

Leslie Threatte (1943-2021), The Grammar of Attic Inscriptions, II: Morphology (Berlin: de Gruyter, 1996), p. 641: In other words, if Threatte's reading is adopted, the youth is saying ἥδομαι (I'm enjoying myself).

This inscription isn't listed in Henry R. Immerwahr, Corpus of Attic Vase Inscriptions, where the vase is mentioned under number 4943.

Changes in the Meaning of Words

Claudian, Against Eutropius 2.206-208 (tr. Maurice Platnauer):

Why give fair names to shameful weakness? Cowardice is called loyalty; fear, a sense of justice.George Orwell, 1984, chapter 1:

quid pulchra vocabula pigris

praetentas vitiis? probitatis inertia nomen,

iustitiae formido subit.

The Ministry of Truth — Minitrue, in Newspeak — was startlingly different from any other object in sight. It was an enormous pyramidal structure of glittering white concrete, soaring up, terrace after terrace, 300 metres into the air. From where Winston stood it was just possible to read, picked out on its white face in elegant lettering, the three slogans of the Party:Cf. Thucydides 3.82.4 (tr. Richard Crawley):WAR IS PEACE

FREEDOM IS SLAVERY

IGNORANCE IS STRENGTH

Words had to change their ordinary meaning and to take that which was now given them. Reckless audacity came to be considered the courage of a loyal ally; prudent hesitation, specious cowardice; moderation was held to be a cloak for unmanliness; ability to see all sides of a question inaptness to act on any. Frantic violence, became the attribute of manliness; cautious plotting, a justifiable means of self-defence.Cf. also B. Hale Wortham, tr., The Śatakas of Bhartṛihari (London: Trübner & Co., 1886), pp. 8-9:

καὶ τὴν εἰωθυῖαν ἀξίωσιν τῶν ὀνομάτων ἐς τὰ ἔργα ἀντήλλαξαν τῇ δικαιώσει. τόλμα μὲν γὰρ ἀλόγιστος ἀνδρεία φιλέταιρος ἐνομίσθη, μέλλησις δὲ προμηθὴς δειλία εὐπρεπής, τὸ δὲ σῶφρον τοῦ ἀνάνδρου πρόσχημα, καὶ τὸ πρὸς ἅπαν ξυνετὸν ἐπὶ πᾶν ἀργόν: τὸ δ᾽ ἐμπλήκτως ὀξὺ ἀνδρὸς μοίρᾳ προσετέθη, ἀσφαλείᾳ δὲ τὸ ἐπιβουλεύσασθαι ἀποτροπῆς πρόφασις εὔλογος.

The moderate man's virtue is called dulness; the man who lives by rigid vows is considered arrogant; the pure-minded is deceitful; the hero is called unmerciful; the sage is contemptuous; the polite man is branded as servile, the noble man as proud; the eloquent man is called a chatterer; freedom from passion is said to be feebleness. Thus do evil-minded persons miscall the virtues of the good.Thanks to Kevin Muse for drawing my attention to Plato, Republic 560e (tr. Paul Shorey):

In celebration of their praises they euphemistically denominate insolence 'good breeding,' licence 'liberty,' prodigality 'magnificence,' and shamelessness 'manly spirit.'Related posts:

ἐγκωμιάζοντες καὶ ὑποκοριζόμενοι, ὕβριν μὲν εὐπαιδευσίαν καλοῦντες, ἀναρχίαν δὲ ἐλευθερίαν, ἀσωτίαν δὲ μεγαλοπρέπειαν, ἀναίδειαν δὲ ἀνδρείαν.

Thursday, June 16, 2022

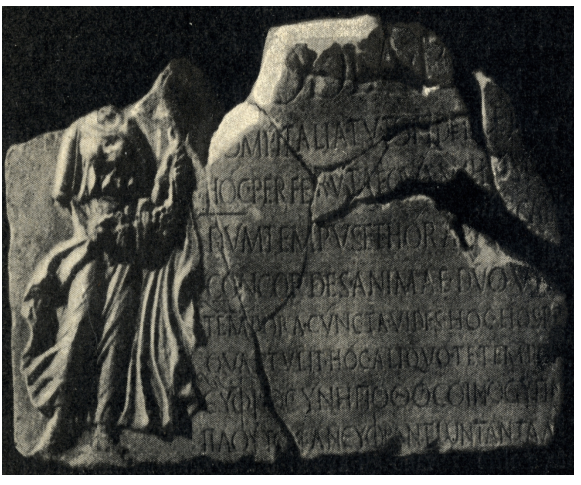

Epitaph for a Roman Freedwoman

Robert E.A. Palmer, "A Poem of All Seasons: AE 1928.108,"

Phoenix 30.2 (Summer, 1976) 159-173 (at 159-160, line numbers added in right margin):

C[l]odia P(ubli) l(iberta) - - - 1Palmer didn't translate the first line, i.e. "Clodia, freedwoman of Publius." Palmer also didn't publish a photograph of the stone, so here it is:

(1) Compitalia tu totidem [qui concelebrasti] / hoc 2

(2) perfer. ut aequa mih[ifuerint Fata aspi]ce. t[um] / dum 3

(3) tempus et hora [mihi, dum suppeditat] quo[que vita], 4

(4) concordes animae duo vix[imus anno]s cas[tos]. 5

(5) Tempora cuncta vides. hoc, hospe[s, te monet hora] 6

(6) quae tulit hoc. aliquo te tempor[e terra tenebit]. 7

(1) εὐφροσύνη, πόθος, οἶνος, ὕπν[ος ταῦτ' ἐστὶ βροτοῖσι] 8

(2) πλοῦτος· ἀνευφράντων Ταντάλ[ου ἐστὶ βίος]. 9

APPARATUS

2 suppl. Palmer totide—et Lugli totide[m] te SEG 3 suppl. Palmer mihi quo Lugli 4 suppl. Palmer ---gas Lugli hora[e---]ga s SEG 5 vix[imus atque perimus Lugli anno]s cas[tos Palmer 6 hospe[s te monet annus Lugli hora Palmer 7 suppl. Lugli 8 ὕπν[ος Lugli ταῦτ' ἐστὶ βροτοῖσι Beazley μόνα ἐστὶ βροτοῖσι Harrison τέρψει σε βιοῦντα De Sanctis 9 Ταντάλ[ου ἐστὶ βίος Beazley τανταλ[ίσει σε κόρῳ De Sanctis

"You who have shared in as many Compitalia, endure this (death of mine). Consider how fair the Fates have been to me. Yesteryear while I (still) had a season and some time, while life, too, was in me, we both lived together in harmony and fidelity."2 "You see all the Seasons (figured here). Time warns you of this, stranger,—Time who brought this. At some season the earth shall hold you. Mirth, love, wine, sleep, these are men's riches; the mournful lead the life of Tantalus."

On the same stone as the inscription a relief of one of the four Seasons (Horae) is sculptured.

2 Duo may modify annos. Hence, "We lived two years in harmony and fidelity."

Withdrawing to the Vanishing Point

M.F.K. Fisher (1908-1992), Map of Another Town: A Memoir of Provence (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1964), p. 10:

It is mainly a question of withdrawing to the vanishing point from the consciousness of the people one is with, before one actually leaves. It is invaluable at parties, testimonial dinners, discussions of evacuation routes in California towns, and coffee-breaks held for electioneering congressmen …

Orcs

Robert Stuart, Tolkien, Race, and Racism in Middle-Earth (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2022), p. 150:

Hearing the 'savage sound' of a chainsaw at work, he would exclaim 'Orcs!' (Sayer 1995, 23). A motorcyclist roaring past would evoke the same outraged exclamation: 'there is an Orc!' (Ordway 2021, 7). For Tolkien, modernity's apparatus of mechanised noise, pollution, and destruction was everywhere 'manned' by Orcs.References (id., p. 162):

Ordway, H. (2021) Tolkien's Modern Reading: Middle-earth Beyond the Middle Ages, Park Ridge IL: Word on Fire Academic.

Sayer, G. (1995) 'Recollections of J.R.R. Tolkien', in P. Reynolds and G. GoodKnight (eds). Proceedings of the J.R.R. Tolkien Centenary Conference, Keble College, Oxford, 1992, Altadena, CA: Mythopoeic Press, pp. 21–25.

Wednesday, June 15, 2022

Professors and Clods

Andrew T. Weil, "Joshua Whatmough," Harvard Crimson (May 3, 1963):

To observe the forms of his eccentricity one might listen to him lecture in Linguistics 100 ("Language"), impressively described in the catalogue of courses as dealing with such topics as the "Theory of Communication," "Language and the Nature of Man," "Language and Literature," and so forth. Actually, when Professor Whatmough lectures in Linguistics 100, he dispenses with these problems in thirty minutes. The rest of the hour gives him a chance to hold forth on everything that he feels needs speaking out against. He does this in the most elegantly precise English to be heard in Cambridge and often illustrates his points with Latin or Greek quotations which he clearly expects his listeners to understand. His manner of delivery varies with his subject. He can be quietly incisive ("A professor should be a person, not a clod. The whole system of Ph.D.'s in certain fields tends to turn professors into clods. I do not have a Ph.D.") or, if the situation demands, violently destructive ("Linguistics has much to offer psychology; psychology has nothing to offer linguistics. And that nothing is wrong.") Certain issues (whether anyone has the right to control what professors say in classes, for one) turn him purple with rage — invariably an awesome transformation. And when it is all over, Whatmough smiles, adjusts his cornflower, takes up his walking stick and leaves the lecture room contented.

Spear and Bow

Calvert Watkins (1933-2013), How to Kill a Dragon: Aspects of Indo-European Poetics (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), pp. 21-22:

Anyone who knows by heart the couplet of the Greek soldier-poet Archilochus (2 IEG):ἐν δορὶ μὲν μοι μᾶζα μεμαγμένη, ἐν δορὶ δ᾽ οἶνοςwith its triple figure of anaphora of the weapon, will surely recognize and respond to the same figure of anaphora, this time five-fold, of another weapon in Rigveda 6.75.2:

Ἰσμαρικός, πίνω δ᾽ ἐν δορὶ κεκλιμένος,

In my spear is my kneaded bread; in my spear

Ismarian wine; I drink leaning on my spear,dhánvanā gā́ dhánvanājíṃ jayema

dhánvanā tīvrā́ḥ samádo jayema

dhánuḥ śátror apakāmáṃ kṛṇoti

dhánvanā sárvāḥ pradíśo jayema

With the bow may we win cattle, with the bow the fight;

with the bow may we win fierce battles.

The bow takes away the enemy's zeal;

with the bow may we win all the regions.

A Know-It-All

Dio Cassius 78.11.5 (on Caracalla; tr. Earnest Cary):

But this same emperor made many mistakes because of the obstinacy with which he clung to his own opinions; for he wished not only to know everything but to be the only one to know anything, and he desired not only to have all power but to be the only one to have power. Hence he asked no one's advice and was jealous of those who had any useful knowledge. He never loved anyone, but he hated all who excelled in anything, most of all those whom he pretended to love most; and he destroyed many of them in one way or another.

ὅτι ὁ αὐτὸς αὐτογνωμονῶν πολλὰ ἐσφάλη· πάντα τε γὰρ οὐχ ὅτι εἰδέναι ἀλλὰ καὶ μόνος εἰδέναι ἤθελε, καὶ πάντα οὐχ ὅτι δύνασθαι ἀλλὰ καὶ μόνος δύνασθαι ἠβούλετο, καὶ διὰ τοῦτο οὔτε τινὶ συμβούλῳ ἐχρῆτο καὶ τοῖς χρηστόν τι εἰδόσιν ἐφθόνει. ἐφίλησε μὲν γὰρ οὐδένα πώποτε, ἐμίσησε δὲ πάντας τοὺς προφέροντας ἔν τινι, μάλιστα δὲ οὓς μάλιστα ἀγαπᾶν προσεποιεῖτο· καὶ αὐτῶν συχνοὺς καὶ διέφθειρεν τρόπον τινά.

Epitaph of Telesistratos

John Granger Cook, Empty Tomb, Resurrection, Apotheosis (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2018 = Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament, 410), p. 227:

Thanks very much to Tim Parkin for sending me the photograph from IGUR III, 1341:

An inscription in Rome, for example, appears on a stone on which are depicted erotic scenes:Unfortunately I haven't been able to see the photograph in Inscriptiones Graecae Urbis Romae. Curavit L. Moretti. Fasciculus IV (1491-1705). Revidenda potiora (Rome: Istituto Italiano per la Storia Antica, 1990), p. 167. The stone is now in Rome (Banco di Sardegna, via Boncompagni 6), according to Moretti, op. cit., p. 165.From Germa Hiera I, Teleistratos [sic, read Telesistratos], repose in the Isles of the Blessed; I want to use these things again! During my life this was the only gain!371 IGUR III, 1341, published originally by F. Cumont, Une pierre tombale érotique de Rome, AntCl 9 (1940) 5–11 (five rows of vulvae, a monstrously erect male, and below a triangle containing the letters ΔΡΜ, another vulva). Cp. the photograph and location in IGUR IV, 1341. Trans. (and discussion) by F. dell'Oro, "Anacreon, the Connoisseur of Desires." An Anacreontic Reading of Menecrates' Sepulchral Epigram (IKyzikos 18, 520 = Merkelbach/Stauber SGO 08/01/47 Kyzikos), in: Imitate Anacreon!: Mimesis, Poiesis, and the Poetic Inspiration in the Carmina Anacreonta, ed. M. Baumbach and N. Dümmler, Berlin 2014, 67–93, esp. 87. SGO is R. Merkelbach and J. Stauber, ed., Steinepigramme aus dem Griechischen Osten, 5 vols., Stuttgart et al. 1998–2004.

Γέρμης ἐξ Ἱερῆς / Τελεσίστρατος ἐν / μακάρων νήσοις κεῖμαι, / ἔτι τῶνδε χρέος ποθέω· / τοῦτο μόνον ζῶν ἐκέρδησα.371

Thanks very much to Tim Parkin for sending me the photograph from IGUR III, 1341:

A Classical Education

Ezra Pound, radio broadcast from 1941, in Ezra Pound Speaking. Radio Speeches of World War II. Edited by Leonard W. Doob (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1978), p. 391:

In fact a classical education WOULD be useful if the universities didn't wrap it in cotton wool, and keep the stewdents from reading the more vital passages.

In fact a little Greek of the right kind or even readin' some with a crib IF you have the real curiosity would be useful.

[....]

When will American college students realize that almost ANY bit of real knowledge would keep 'em from being dead rabbits? Aristotle, Demosthenes, Mencius or Confucius, all antidotes to bein' suckers.

[....]

And of course it is a mere matter of opinion, but it WAS Aristotle's opinion, expressed in the 5th book of his Politics, that the three qualities which supreme magistrates ought to possess are loyalty to established constitutions; secondly, great capacity for the duties of the office; and thirdly, virtue and justice.

Tuesday, June 14, 2022

Epitaph of Philetos

Richmond Lattimore, Themes in Greek and Latin Epitaphs (1935; rpt. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1962), p. 84:

μηδὲν ἄγαν φρονέων, θνητὰ δὲ πάνθ' ὁρόω[νThe order of the clauses is mixed up in Lattimore's translation. I would revise it as follows:

ἦλθον, ἀπῆλθον ἄμεμπτος, ἃ μὴ θέμις οὐκ ἐδόκευσα,

εἴτ' ἤμην πρότερον, εἴτε χρόνοις ἔσομαι.472

I believed in overdoing nothing. I came and went away blameless. I observed everything human, but did not pry into what is forbidden, or seek to know whether I existed before or whether I ever shall again.

472 EG 615, 4-6 (Sena Gallica, 2d or 3d cent. A.D.). For further variations in Greek, cf. IGR 3, 1438; Ramsay 635; Cumont, op. cit.

I believed in overdoing nothing. I observed everything human. I came and went away blameless. I did not pry into what is forbidden, whether I existed before or whether I ever shall again.Cf. the translation of the entire inscription in G.H.R. Horsley, New Documents Illustrating Early Christianity, Vol. 4: A Review of Greek Inscriptions and Papyri published in 1979 ([North Ryde:] Ancient History Documentary Research Centre, Macquarie University, 1987), p. 32:

To the underworld gods. I was like I was in my speech, spirit, and form, possessing the implanted soul of a person just born, happy in friendship and fortunate in my mind, holding the view 'nothing in excess', and viewing everything as mortal. I came (i.e., into the world), I departed blameless, I did not think about things which I ought not to: whether I had a previous existence, whether I shall have one in time (to come). I was educated, I educated (others), I shackled the vault of the universe, declaring to men the divine virtues which proceed from the gods. The dear earth conceals me; yet what was my pure name? I was Philetos, a man beloved by all, from Limyra in Lykia.See also Andrzej Wypustek, "Laughing in the Face of Death: a Survey of Unconventional Hellenistic and Greek-Roman Funerary Verse-Inscriptions," Klio 103 (2021) 160-187 (at 170-171).

Numberless Barbarian Hordes

Ammianus Marcellinus 31.4.6 (tr. John C. Rolfe):

With such stormy eagerness on the part of insistent men was the ruin of the Roman world brought in. This at any rate is neither obscure nor uncertain, that the ill-omened officials who ferried the barbarian hordes often tried to reckon their number, but gave up their vain attempt; as the most distinguished of poets says [Vergil, Georgics 2.105-106]:Related post: Refugees.Who wishes to know this would wish to knowita turbido instantium studio orbis Romani pernicies ducebatur. illud sane neque obscurum est neque incertum, infaustos transvehendi barbaram plebem ministros, numerum eius comprehendere calculo saepe temptantes, conquievisse frustratos, "quem qui scire velit" ut eminentissimus memorat vates, "Libyci velit aequoris / idem discere quam multae zephyro truduntur harenae."

How many grains of sand on Libyan plain

By Zephyrus are swept.

ducebatur V: adducebatur Mommsen: augebatur Heraeus

truduntur V: turbentur A, codd. Vergilii

Repertories of Conjectures

Egil Kraggerud, Critica: Textual Issues in Horace, Ennius, Vergil and Other Authors (Abingdon: Routledge, 2020), p. 15, with note on p. 27:

Only in the case of a small handful of ancient authors7 have there been serious undertakings in more recent times to collect the whole output of conjectures. A full survey of conjectures from the start of the printing era until the present day, however, is an indispensable prerequisite for any critical editing of a classical text, no less so than a complete catalogue is necessary to the user of a library. That few scholars have so far given priority to the matter should not be normative for future priorities among scholars. The drawbacks and calamities following in the wake of ignorance are, of course, difficult to measure like any contra-factual evaluation. To cut the argument short, however: easily available complete information in this regard would be a particular boon to editors and commentators alike, and I am equally sure that time-saving repertories of conjectures would have much to offer philologists in general as well.In the note, make the following corrections:

7 Aeschylus: R.D. Dawe, Repertory of Conjectures on A., Leiden: Pindar, 1965; D.E. Gerber, Emendations in Pindar 1513–1972, Amsterdam: Hakkert, 1976. — Sophocles: L. van Paassen (not printed, but gratefully consulted by editors of Sophocles: R.D. Dawe and H. Lloyd-Jones – N.G. Wilson. — Catullus: D. Kiss, An Online Repertory of Conjectures, Catullus Online. — Propertius): W. R. Smyth, Thesaurus criticus ad Sexti Propertii textum, Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1970; Seneca: M. Billerbeck – M. Somazzi, Repertorium der Konjekturen in den Seneca-Tragödien [Mnemosyne. Suppl. 316], Leiden: Brill 2009.

- For "Leiden: Pindar, 1965;" read "Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1965; Pindar —"

- For "Propertius):" read "Propertius:"

Carpe Diem

Jacques Perret (1906-1992), Horace, tr. Bertha Humez ([New York:] New York University Press, 1964), pp. 94-95:

The famous phrase Carpe diem, "Pluck the passing day," makes us grasp, I believe, one of the most essential aspects of Horace's moral personality. It is, naturally, in rapport with his temperament: this man of Mercury had the mobility of quicksilver; he was impulsive and volatile. Nevertheless, it is doubtful that he would have adopted this point of view if he had not attributed a true moral value to it. In fact, he places it in opposition to those vices that always most horrified him and that he battled all his life. One of the greatest reproaches that he makes against ambition and the love of riches is that these passions mortgage and annul the present—which one neglects to experience for what it is—in favor of a future that is surely chimerical, since, even if it were to be realized, and nothing is less certain, one would turn away from it at once: for one would not know how to live in it, forever driven on by the same incapacity that makes us strangers to the time in which we are living now. In future projects Horace always feared a treason to the present, the surest mark of moral instability and weakness.Id., pp. 96-97:

Horace, then, did not like to think of the future. For him, tomorrow was the place not of hope but of uncertainties, and it was better not to try to dissipate these, for the only certitude that one risked finding instead was death. Yet death has a considerable place in the Odes, and it is clear that Horace did not like it. He did not seek to dress it up, or to volatilize it, or to persuade himself that it is a natural phenomenon that we should accept with indifference or at least without sadness. On that head, how little of an Epicurean he is! He did not succeed—but very rare, I think, are those who do—in living really entirely in the succession of present instants. Instead of feeling moment grains under his fingers like so many infrangible diamonds, he had a feeling of evanescence, and in the presence of that feeling he was without recourse. Most of us escape that anguish only by placing all our interest, all our love, in some great continuity external to ourselves, the fortunes of which will not be compromised by our own death. Horace's morality does not offer him this remedy. Should we pity him? Pity and condemn him both? If we could undertake a dialogue with him, would he not have much to say to us on the inhumanity, oversimplifications, and rejections that our behavior often dissimulates?The translation seems awkward in parts, e.g. "Instead of feeling moment grains under his fingers like so many infrangible diamonds," where the French reads "Au lieu de sentir sous ses doigts la granulation des moments comme autant de diamants infrangibles."

Monday, June 13, 2022

Bloods

Jacob Wackernagel (1853-1938), Lectures on Syntax, ed. and tr. David Langslow (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), p. 18 (editor's footnotes omitted):

In the earliest period, Christian texts in Latin are almost exclusively translations from Greek texts, translations, moreover, which were made not by the intellectual elite but by simple people of limited education and learning, for whom the wording of the original was surrounded by a sacred halo. As a result, when they produced versions of holy texts, they committed gross infringements of the rules of their own language. For example, in an old translation of the New Testament, which is known in fragments—i.e., not in the Vulgate—we read at Mark 4:11 omnia dicitur, 'all things (pl.) is said (sg.)'. In Latin it is a glaring solecism to use a singular verb with a plural subject. This is explained by the fact that the Greek original has πάντα γίγνεται 'everything (pl.) comes to pass (sg.)', with the familiar Greek construction (neuter plural subject with singular verb; cf. I, 101–3 below). Similarly, in the so-called Clementina, Greek participles in the genitive absolute are rendered with genitives in the Latin, e.g. §43 contendentium tribuum, 'while the tribes were disputing'. Or again, in just the same way it can happen that in texts of the Bible even Hebraisms enter Latin. Several times in the Old Testament we have the expression ἀνὴρ αἱμάτων (lit. 'man of bloods (pl.)': 2 Kings 16:7, 8; Psalms 5:7, 25:9, etc.; Proverbs 29:10). From a Greek point of view the descriptive genitive is anomalous and so, too, is the plural, 'bloods' (αἵματα occurs only in poetry). Both features are conditioned by the Hebrew original, and accordingly the phrase used in the Latin text is uir sanguinum. This is particularly striking because sanguis in Latin has otherwise no plural at all; the grammarians, who take no notice of Christian Latin, make this an explicit rule (Servius on Aen. 4.687; Priscian 5.54 = GL II, 175).Servius on Aen. 4.687:

nec sanguines dicimus numero plurali nec cruores.See also Augustine, Enarrationes in Psalmos 50.16:

expressit latinus interpres verbo minus latino proprietatem tamen ex graeco. nam omnes novimus latine non dici sanguines, nec sanguina; tamen quia ita graecus posuit plurali numero, non sine causa, nisi quia hoc invenit in prima lingua hebraea, maluit pius interpres minus latine aliquid dicere, quam minus proprie.

An Anti-Intellectual

Dio Cassius 78.11.2 (on Caracalla; tr. Earnest Cary):

Indeed, he had no regard whatever for the higher things, and never even learned anything of that nature, as he himself admitted; and hence he actually held in contempt those of us who possessed anything like education.

οὐδὲν γὰρ τῶν καλῶν ἐλογίζετο· οὐδὲ γὰρ ἔμαθέ τι αὐτῶν, ὡς καὶ αὐτὸς ὡμολόγει, διόπερ καὶ ἐν ὀλιγωρίᾳ ἡμᾶς τούς τι παιδείας ἐχόμενον εἰδότας ἐποιεῖτο.

A Good Death

Leslie Mitchell, Maurice Bowra: A Life (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), p. 302, with notes on p. 364: