Saturday, July 31, 2021

Powerful is the Desire for the Fatherland

Friedrich Schiller, William Tell, lines 838-850 (Attinghausen to his nephew Rudenz; from Act II, Scene 1; tr. Sidney E. Kaplan):

Deluded boy, seduced by empty show!

Despise your land of birth! Be ashamed

of the good old customs of your fathers!

With burning tears you will some day

long for home, for the hills of your fathers

and the melody of this herd song

which you scorn in proud disgust.

With pain and longing it will move you

when it strikes your ear in the foreign land.

Oh, powerful is the love for one's native land!

The strange, false world is not for you.

There at the proud court with your true heart

you will remain forever a stranger to yourself.

Verblendeter, vom eiteln Glanz verführt!

Verachte dein Geburtsland! Schäme dich

Der uralt frommen Sitte deiner Väter!

Mit heißen Thränen wirst du dich dereinst

Heim sehnen nach den väterlichen Bergen,

Und dieses Heerdenreihens Melodie,

Die du in stolzem Ueberdruß verschmähst,

Mit Schmerzenssehnsucht wird sie dich ergreifen,

Wenn sie dir anklingt auf der fremden Erde.

O mächtig ist der Trieb des Vaterlands!

Die fremde falsche Welt ist nicht für dich,

Dort an dem stolzen Kaiserhof bleibst du

Dir ewig fremd mit deinem treuen Herzen!

Friday, July 30, 2021

Away With Him!

William Shakespeare, Henry VI, Part II, 4.7.60 (Pope Francis Jack Cade speaking):

Away with him, away with him! He speaks Latin.

The Modern Age

Friedrich Nietzsche, Unpublished Fragments from the Period of Thus Spoke Zarathustra (Summer 1882-Winter 1883/84), tr. Paul S. Loeb and David F. Tinsley (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2019 = The Complete Works of Friedrich Nietzsche, vol. 14), p. 556 (Notebook 22, number 1):

It is the age of puny people.Friedrich Nietzsche, Nachgelassene Fragmente 1882-1884, edd. Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari, 2. Aufl. (Munich: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, 1988 = Kritische Studienausgabe, Bd. 10), p. 614:

Es ist die Zeit der kleinen Leute.Cf. Juvenal 15.69-71:

For the human race was already going downhill when Homer was alive; now the earth brings forth bad and puny men. Therefore whatever god has set eyes on us laughs and despises us.

nam genus hoc vivo iam decrescebat Homero,

terra malos homines nunc educat atque pusillos;

ergo deus, quicumque aspexit, ridet et odit.

Because I Said So

Juvenal 6.223 (tr. Peter Green):

I want, I command it: let my will suffice as reason.

hoc volo, sic iubeo, sit pro ratione voluntas.

No Escape

Homer, Iliad 22.300-301 (tr. Richmond Lattimore):

And now evil death is close to me, and no longer far away,Nicholas Richardson ad loc.:

and there is no way out.

νῦν δὲ δὴ ἐγγύθι μοι θάνατος κακός, οὐδ᾽ ἔτ᾽ ἄνευθεν,

οὐδ᾽ ἀλέη.

For 300 cf. 16.853 (Patroklos to Hektor) = 24.132 (Thetis to Akhilleus) ἄγχι παρέστηκεν θάνατος καὶ μοῖρα κραταιή. ἀλέη ('escape') occurs only here in Homer. Cf. Hes. Erga 545, and Hippocrates, Aer. 19; ἀλεωρή 3x Il.Cf. also the verb ἀλέομαι = avoid, shun, flee.

Thursday, July 29, 2021

Koinonia

M.I. Finley, "Leaders and Followers," in his Democracy Ancient and Modern, 2nd ed. (London: The Hogarth Press, 1985), pp. 3-37 (at 29):

Koinonia is hard to translate by a single English word: it has a cluster of meanings, including, for example, business partnership, but here we must think of "community" with a strong inflection, as in the early Christian community, in which the bonds were not merely propinquity and a common way of life but also a consciousness of common destiny, common faith. For Aristotle man was by nature not only a being destined to live in a city-state but also a household being and a community being.

People Lived Differently Then

Juvenal 6.11-12 (tr. Susanna Morton Braund):

You see, people lived differently then, when the world was new and the sky was young...Commentators compare Lucretius 5.907 (tellure nova caeloque recenti).

quippe aliter tunc orbe novo caeloque recenti

vivebant homines...

Wednesday, July 28, 2021

A Sort of Second Body

George Santayana, The Life of Reason, or The Phases of Human Progress: Reason in Religion (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1905), pp. 186-187:

Patriotism is another form of piety in which its natural basis and rational function may be clearly seen. It is right to prefer our own country to all others, because we are children and citizens before we can be travellers or philosophers. Specific character is a necessary point of origin for universal relations: a pure nothing can have no radiation or scope. It is no accident for the soul to be embodied; her very essence is to express and bring to fruition the body's functions and resources. Its instincts make her ideals and its relations her world. A native country is a sort of second body, another enveloping organism to give the will definition. A specific inheritance strengthens the soul. Cosmopolitanism has doubtless its place, because a man may well cultivate in himself, and represent in his nation, affinities to other peoples, and such assimilation to them as is compatible with personal integrity and clearness of purpose. Plasticity to things foreign need not be inconsistent with happiness and utility at home. But happiness and utility are possible nowhere to a man who represents nothing and who looks out on the world without a plot of his own to stand on, either on earth or in heaven. He wanders from place to place, a voluntary exile, always querulous, always uneasy, always alone. His very criticisms express no ideal. His experience is without sweetness, without cumulative fruits, and his children, if he has them, are without morality. For reason and happiness are like other flowers—they wither when plucked.

First Person Plural Possessive Pronoun

Leo Spitzer (1887-1960), "The Addresses to the Reader in the'Commedia," Italica

32.3 (September, 1955) 143-165 (at 151), calls the first person plural possessive pronoun

the "possessive of human solidarity."

Dinner Menu

Kenneth Rexroth, Complete Poems (Port Townsend: Copper Canyon Press, 2004), pp. 358-359:

Dinner in a peasant auberge,

Everybody inspects the

Vélos. "De Paris en Italie?

Incroyable! Formidable!"

Grilled pork chops, fried potatoes,

Tomatoes, beans in vinegar,

Fresh cheese, pears, wine, and coffee,

And the magnificent bread

Of Touraine. Just looking at it,

We weep for joy after the

Rancid papier mâché turds

They sell in Paris. We shake

Hands with everybody and

Pedal on down the river,

Wobbling, heavy with food.

A Taste for Simplicity

George Santayana, letter to Shohig Sherry Terzian (December 27, 1937):

As I grow old, I feel reviving in myself an opposite instinct, a Castilian love of mended clothes, simple monotonous days, and a minimum of belongings.

Toy Trumpeters

Friedrich Nietzsche, Unpublished Fragments from the Period of Thus Spoke Zarathustra (Summer 1882-Winter 1883/84), tr. Paul S. Loeb and David F. Tinsley (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2019 = The Complete Works of Friedrich Nietzsche, vol. 14), p. 538 (Notebook 20, number 13):

The solemn toy trumpeters, who with their melodies preach dreary doctrines and lies.Friedrich Nietzsche, Nachgelassene Fragmente 1882-1884, edd. Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari, 2. Aufl. (Munich: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, 1988 = Kritische Studienausgabe, Bd. 10), p. 595:

Die feierlichen Schnurrpfeifer, die mit Tönen düstere Lehren und Lügen predigen.

Tuesday, July 27, 2021

Not Altogether Fruitless

Poggio Bracciolini, Letters I.8 (to Niccolò Niccoli, tr. Phyllis Walter Goodhart Gordan):

But this reading of mine is not altogether fruitless. I learn a little something every day, even if only superficially, and this is the reason why my love of Greek literature has come back so strong...

nec est tamen omnino inutilis haec lectio; disco aliquid in diem, saltem superficie tenus, et haec est causa potissime, cur amor graecarum litterarum redierit...

What Stupidity Looks Like

Cyprian of Antioch, Confession and Martyrdom 13 (Coptic version, tr. Anthony Alcock):

I saw the likeness of stupidity with a head as small as a nut...Id. (Greek version, with numbering 4.2, tr. Ryan Bailey):

I saw ... the form of folly, having the head of a nut...Cf. Adamantius the Sophist, Physiognomonica B30, in Richard Foerster, ed., Scriptores Physiognomonici, Vol. I (Leipzig: B.G. Teubner, 1893), p. 381 (tr. Ian Repath):

εἶδον ... εἶδος μωρίας, κεφαλὴν ἔχον καρύου...

A very small head indicates an insensible and unintelligent man...

κεφαλὴ μικρὰ πάνυ ἀναίσθητον καὶ ἀσύνετον σημαίνει...

Down With Everything Philological

Francis Bacon (1561-1626), Novum Organum, Aphorisms 3 (tr. Anthony Grafton):

Down with antiquities and citations or supporting testimonies from texts; down with debates and controversies and divergent opinions; down with everything philological.Oxford Latin Dictionary, s.v. facesso, sense 3: "To go away, depart, be off," here jussive subjunctive, 3rd person plural, with subjects antiquitates, etc.

Primo igitur facessant antiquitates, et citationes, aut suffragia auctorum; etiam lites et controversiae et opiniones discrepantes; omnia denique philologica.

Monday, July 26, 2021

A World Without Media

M.I. Finley, "Leaders and Followers," in his Democracy Ancient and Modern, 2nd ed. (London: The Hogarth Press, 1985), pp. 3-37 (at 17-18):

"A state composed of too many," Aristotle wrote in a famous passage (Politics, 1326b3-7), "will not be a true state, for the simple reason that it can hardly have a true constitution. Who can be the general of a mass so excessively large? And who can be herald, except Stentor?"Id. (at 22, discussing Thucydides 6.24.3-4):

The reference to the herald (the town crier) is illuminating. The Greek world was primarily one of the spoken, not the written, word. Information about public affairs was chiefly disseminated by the herald, the notice board, gossip and rumour, verbal reports and discussions in the various commissions and assemblies that made up the governmental machinery. This was a world not only without mass media but without media at all, in our sense. Political leaders, lacking documents that could be kept secret (apart from the occasional exception), lacking media they could control, were of necessity brought into a direct and immediate relationship with their constituents, and therefore under more direct and immediate control.

It would be easy to preach about the irrationality of crowd behaviour at an open-air mass meeting, swayed by demagogic orators, chauvinistic patriotism and so on. But it would be a mistake to overlook that the vote in the Assembly to invade Sicily had been preceded by a period of intense discussion, in the shops and taverns, in the town square, at the dinner table—a discussion among the same men who finally came together on the Pnyx for the formal debate and vote. There could not have been a man sitting in the Assembly that day who did not know personally, and often intimately, a considerable number of his fellow-voters, his fellow-members of the Assembly, including perhaps some of the speakers in the debate. Nothing could be more unlike the situation today, when the individual citizen from time to time engages, along with millions of others, not just a few thousand of his neighbours, in the impersonal act of marking a ballot-paper or manipulating the levers of a voting-machine.

Verbal Retaliation

Euripides, Alcestis 704-705 (tr. Edward P. Coleridge):

Yet if thou wilt speak ill of me, thyself shalt hear a full and truthful list of thy own crimes.Related posts:

εἰ δ᾽ ἡμᾶς κακῶς

ἐρεῖς, ἀκούσῃ πολλὰ κοὐ ψευδῆ κακά.

Philology

Edward W. Said (1935-2003), Humanism and Democratic Criticism (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004), p. 57:

Philology is just about the least with-it, least sexy, and most unmodern of any of the branches of learning associated with humanism...Id., p. 61:

For a reader of texts to move immediately, however, from a quick, superficial reading into general or even concrete statements about vast structures of power or into vaguely therapeutic structures of salutary redemption (for those who believe that literature makes you a better person) is to abandon the abiding basis for all humanistic practice. That basis is at bottom what I have been calling philological, that is, a detailed, patient scrutiny of and a lifelong attentiveness to the words and rhetorics by which language is used by human beings who exist in history...

The Gods Are There

Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff (1848-1931), Der Glaube der Hellenen, I (Berlin: Weidmannsche Buchhandlung, 1931), p. 17 (tr. Egon Flaig):

The gods exist. The first prerequisite for understanding the belief and the cult of the Greeks is that we realise and accept this as a given fact just as they did. Knowledge of their existence is based on a perception, be it internal or external, be it the perception of the godhead itself or of something in which we discern its effect.

Die Götter sind da. Daß wir dies als gegebene Tatsache mit den Griechen erkennen und anerkennen, ist die erste Bedingung für das Verständnis ihres Glaubens und ihres Kultus. Daß wir wissen, sie sind da, beruht auf einer Wahrnehmung, sei sie innerlich oder äußerlich, mag der Gott selbst wahrgenommen sein oder etwas, in dem wir die Wirkung eines Gottes erkennen.

Sunday, July 25, 2021

Of Little Worth

Friedrich Nietzsche, Unpublished Fragments from the Period of Thus Spoke Zarathustra (Summer 1882-Winter 1883/84), tr. Paul S. Loeb and David F. Tinsley (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2019 = The Complete Works of Friedrich Nietzsche, vol. 14), p. 481(Notebook 17, number 1):

Everything that can be bought is worth little: I spit this doctrine into the faces of hucksters.Friedrich Nietzsche, Nachgelassene Fragmente 1882-1884, edd. Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari, 2. Aufl. (Munich: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, 1988 = Kritische Studienausgabe, Bd. 10), p. 533:

Alles was bezahlt werden kann ist wenig werth: diese Lehre speie ich den Krämern ins Gesicht.

Disapproval of Educational Innovations

Suetonius, On Rhetoricians 1, quoting an edict of the censors Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus and Lucius Licinius Crassus from

92 B.C.

(tr. J.C. Rolfe):

Our forefathers determined what they wished their children to learn and what schools they desired them to attend. These innovations in the customs and principles of our forefathers do not please us nor seem proper.Also quoted by Aulus Gellius 15.11.2.

maiores nostri, quae liberos suos discere et quos in ludos itare vellent, instituerunt. haec nova, quae praeter consuetudinern ac morem maiorum fiunt, neque placent neque recta videntur.

The Oppressor

Friedrich Schiller, William Tell, lines 704-705 (from Act I, Scene 4; my translation):

But he who oppresses us is our emperor

And highest judge...

Doch der uns unterdrückt, ist unser Kaiser

Und höchster Richter...

Preparedness

Alcaeus, fragment 140 Voigt, tr. C.M. Bowra, Greek Lyric Poetry from Alcman to Simonides, 2nd rev. ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1961), pp. 137-138:

The great house glitters with bronze, and the whole roof is well decked with gleaming helmets, from which white plumes of horse-hair hang waving, to deck the heads of men. Bright greaves of bronze lie round pegs and hide them—a protection against the strong arrow,—and corslets of new linen and hollow shields lie thrown upon the floor. With them are swords from Chalcis, and with them many belts and tunics. These we may not forget, ever since we first stood to this task.The Greek, adapted from Eva-Maria Voigt, ed., Sappho et Alcaeus, Fragmenta (Amsterdam: Athenaeum, 1971), p. 242:

]...[Herbert Weir Smyth, Greek Melic Poets (London: Macmillan and Co., Limited, 1900), pp. 223-224 (with different line numbering): David A. Campbell, Greek Lyric Poetry : A Selection of Early Greek Lyric, Elegiac and Iambic Poetry (1982; rpt. London: Bristol Classical Press, 1998), pp. 303-304 (with different line numbering): Bowra, op. cit., p. 138 (footnotes omitted):

μαρμαίρει δὲ μέγας δόμος

χάλκωι, παῖσα δ᾿ Ἄρηι κεκόσμηται στέγα

λάμπραισιν κυνίαισι, κὰτ

τᾶν λεῦκοι κατέπερθεν ἴππιοι λόφοι 5

νεύοισιν, κεφάλαισιν ἄν-

δρων ἀγάλματα· χάλκιαι δὲ πασσάλοις

κρύπτοισιν περικείμεναι

λάμπραι κνάμιδες, ἔρκος ἰσχύρω βέλεος,

θόρρακές τε νέω λίνω 10

κόϊλαί τε κὰτ ἄσπιδες βεβλήμεναι·

πὰρ δὲ Χαλκίδικαι σπάθαι,

πὰρ δὲ ζώματα πόλλα καὶ κυπάσσιδες.

τῶν οὐκ ἔστι λάθεσθ᾿ ἐπεὶ

δὴ πρώτιστ᾿ ὐπὰ τὦργον ἔσταμεν τόδε. 15

3 Ἄρηι codd.: ἄρ' εὖ Page

15 πρώτιστ᾿ ὐπὰ τὦργον Lobel: πρώτισθ᾿ ὑπὸ ἔργον codd.

Alcaeus marks the arms and the armour with a keen eye and registers each item in turn. Though such an armoury is clearly intended for use, it has its own charm for him, and he delights in it as an aristocrat delights in the apparatus of his sport. The arms so described are contemporary and the best that money can buy. If the helmets, with their horse-hair plumes, are not so up to date as the plumeless Corinthian helmet, which was already in full use on the Greek mainland, but have a Homeric air, the 'hollow' shields came into existence with the introduction of hoplite tactics in the seventh century, and the adjective is much to the point. The linen corslets are not so much a means of protection as a military elegance; they recall those which Amasis of Egypt dedicated in the temple of Athene at Lindos and sent to Sparta. The ζώματα and the κυπάσσιδες complete the inventory of what a full uniform required. The whole passage suggests an officer who enjoys the inspection of kit and looks forward with confidence to the good use that will be made of it.The same fragment, tr. Richmond Lattimore, Greek Lyrics, 2nd ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1960), pp. 44-45:

The great hall is aglare with bronze armament and the whole inside made fit for warOn this fragment see Denys Page, Sappho and Alcaeus: An Introduction to the Study of Ancient Lesbian Poetry (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1955), pp. 209-223, and Henry Spelman, "Alcaeus 140," Classical Philology 110.4 (October 2015) 353-360.

with helms glittering and hung high, crested over with white horsemanes that nod and wave

and make splendid the heads of men who wear them. Here are shining greaves made out of bronze,

hung on hooks, and they cover all the house's side. They are strong to stop arrows and spears.

Here are war-jackets quilted close of new linen, with hollow shields stacked on the floor,

with broad swords of the Chalkis make, many tunics and many belts heaped close beside.

These shall not lie neglected, now we have stood to our task and have this work to do.

Saturday, July 24, 2021

For Our Ancestral Heritage

Orm Øverland, The Western Home: A Literary History of Norwegian America ([Northfield]: The Norwegian American Historical Association, 1996), pp. 203, 205 (note omitted):

The front lines between the proponents of language retention and of Anglicization had hardened during and after the First World War. Wist, who in 1904 had spoken of the transitional character of the immigrant culture, now seemed a preservationist compared to those who questioned the patriotism of any American who used a foreign language. The new church formed in 1917 had identified itself as "Norwegian" but wartime nativist pressure led to a resolution (533 voting yes, 61, no) at the first biennial convention in 1918 to drop this adjective. The resolution had to be confirmed by a second biennial meeting, and the opposition mobilized, forming a society, For Fædrearven (For our ancestral heritage), with the purpose of keeping the church "Norwegian." The prime mover and secretary was [Ole] Rølvaag. In a newspaper in Canton, South Dakota, Visergutten, he wrote a series of articles and edited a debate on Norwegian-American culture (3 Feb. 1921-15 June 1924, eventually publishing his contributions in 1922 in Omkring fædrearven (On our ancestral heritage). As nativist sentiment subsided with the end of the war and a disruptive debate on a non-theological issue was foreseen, leaders of the church themselves recommended that the convention reverse its position in 1920 (Chrislock 1977, 220-221). The spokesmen for "our heritage" had won the battle against what had seemed significant odds. Indeed the ground swell of sympathy for the preservationist stance not only demonstrated a reaction to the experience of near persecution of minority cultures but seemed to augur a revitalization of Vesterheimen. The Norwegian Society had never gained popular support in the early years of the century; For Fædrearven could boast annual meetings with several thousand participants (Rolvaag 1922,17).

In the first of the three essays in his 1922 volume, "Naive reflections on our heritage," Rølvaag develops a theory of ethnicity and describes the traits and characteristics that Norwegian Americans may contribute to their new country. While this essay presents the most complete statement of the preservationist views shared by Ager, Buslett, Johnson, and Strømme, the other two essays are more polemical in tone and add little to the theory or the rhetoric of the first. Nostalgia for the Old World has no place in Rølvaag's reflections; he speaks as a Norwegian American, not as a Norwegian. In keeping with the terminology of his day, Rølvaag speaks of "race" where we would speak of ethnicity and he may at times seem to suggest that national traits are not merely cultural but are transferred genetically. Nevertheless, his message to his readers is less concerned with what they are than with what they must do. His appeals to ethnic pride must be understood in a context where the ideologues of Americanism were suggesting that the traits of immigrants were not only undesirable but inferior. In his conclusion to the first essay he speaks to the heart of the matter, the "sancta sanctorum: our emotional relationship to the land we have become citizens of and where our children will live and build after us." He asks how someone with a "Norwegian soul" may become a good American citizen, and replies: "let us hold high our heritage; then our emotional relationship to America will be all right. For this land needs human beings, not merely creatures" (107-108. Italics are Rølvaag's.).

His implied antagonists are the spokesmen for the melting-pot ideology, who appear to be near relatives of Ibsen's Button Molder. In the last act of Peer Gynt the Button Molder explains that since Peer had failed to realize himself in life, he would go neither to hell nor to heaven but would be melted down by orders of a "thrifty" Master who "throws out nothing as irreparable / That still can be used for raw material." Peer protests that even "the old-time judgment" would be better than "simply to disappear / Like a mote in a stranger's blood, to forswear / being Gynt for a ladle-existence, to melt—/ It makes my innermost soul revolt." But he meets little understanding from the Button Molder, who points out that "Yourself is just what you've never been—/ So what difference to you to get melted down?" Literate Norwegian Americans were preconditioned to react negatively to Israel Zangwill's vision of America in The Melting-Pot (1909), and Rølvaag merges Ibsen's metaphor of the "melting ladle" with Zangwill's "melting pot": "We cannot be reconciled to the doctrine that it would benefit our country if all its inhabitants become identical, molded in the same ladle, with all dissimilarities ground away. We believe this would impoverish us as a people" (1922,22).

Letters of the Alphabet as Analogues for Atoms

Lucretius 1.817-829 (tr. Ronald Latham):

It often makes a big difference in what combinations and positions the selfsame elements occur, and what motions they mutually pass on or take over. For the same elements compose sky, sea and lands, rivers and sun, crops, trees and animals, but they are moving differently and in different combinations. Consider how in my verses, for instance, you see many letters common to many words; yet you must admit that different verses and words differ in substance and in audible sound. So much can be accomplished by letters through mere change of order. But the elements can bring more factors into play so as to create things in all their variety.I don't have access to Cyril Bailey's commentary on Lucretius, so I'm forced to rely on William Barney Smith's (Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1942), who has these observations on this passage (p. 281): I also don't have access to Wilson H. Shearin, "Saussure's cahiers and Lucretius' elementa: A Reconsideration of the Letters-Atoms Analogy," in Donncha O'Rourke, ed., Approaches to Lucretius: Traditions and Innovations in Reading the De Rerum Natura (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020), pp. 140-156, although I was able to extract this footnote (p. 141, n. 4) from Google Books:

atque eadem magni refert primordia saepe

cum quibus et quali positura contineantur

et quos inter se dent motus accipiantque;

namque eadem caelum mare terras flumina solem 820

constituunt, eadem fruges arbusta animantis,

verum aliis alioque modo commixta moventur.

quin etiam passim nostris in versibus ipsis

multa elementa vides multis communia verbis,

cum tamen inter se versus ac verba necessest 825

confiteare et re et sonitu distare sonanti.

tantum elementa queunt permutato ordine solo;

at rerum quae sunt primordia, plura adhibere

possunt unde queant variae res quaeque creari.

Anti-Clerical Sentiments

Friedrich Nietzsche, Unpublished Fragments from the Period of Thus Spoke Zarathustra (Summer 1882-Winter 1883/84), tr. Paul S. Loeb and David F. Tinsley (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2019 = The Complete Works of Friedrich Nietzsche, vol. 14), pp. 388-389 (Notebook 13, number 1):

Black ponds from which the sweet gloom of a toad sings forth: this is what you are to me, you priests. Who among you could stand to show himself naked!Friedrich Nietzsche, Nachgelassene Fragmente 1882-1884, edd. Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari, 2. Aufl. (Munich: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, 1988 = Kritische Studienausgabe, Bd. 10), pp. 433-434:

You do well to lay out your corpse in black, and I hear the evil-spiced dullness of death chambers resounding from your speeches.

How I hate the lying convulsions of your humility! In your kneeling I see the habits of slaves, you lickspittles of your God!

Schwarze Teiche, aus denen heraus der süße Trübsinn der Unke singt: das seid ihr mir, ihr Priester. Wer von euch vertrüge es, sich nackt zu zeigen!

Ihr thut gut, euren Leichnam schwarz auszuschlagen, und aus euren Reden klingt mir die übel gewürzte Dumpfheit von Todtenkammern.

Wie hasse ich den verlogenen Krampf eurer Demuth! Eurem Kniefall sehe ich die Gewohnheiten der Sklaven an, ihr Speichellecker eures Gottes!

Long Live the People and the Crafts!

Stephen Greenblatt, The Swerve: How the World Became Modern (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2011), pp. 114-115:

Some of the most skilled of these [cloth workers] were organized in powerful guilds that looked out for their interests, but other workmen labored for a pittance. In 1378, two years before Poggio's birth, the seething resentment of these miserable day laborers, the populo minuto, had boiled over into a full-scale bloody revolt. Gangs of artisans ran through the streets, crying, "Long live the people and the crafts!" and the uprising briefly toppled the ruling families and installed a democratic government. But the old order was quickly restored, and with it a regime determined to maintain the power of the guilds and the leading families.In his endnotes Greenblatt provides no sources for this passage. His populo minuto seems to be a misprint for popolo minuto. In Italian the cry was apparently "Viva il popolo et l'arti!" See Il controtumulto de' Ciompi: Lettera del secolo XIV (Florence: Tipografia all'Insigna di S. Antonio, 1869), p. 10. Other sources record a similar cry — Viva il popolo minuto, i.e., Long live the little people, which would be a good slogan for a modern populist movement.

After the defeat of the Ciompi, as the working-class revolutionaries were called, the resurgent oligarchs held on to power tenaciously for more than forty years, shaping Poggio's whole knowledge and experience of the city where he determined to make his fortune.

Labels: typographical and other errors

Friday, July 23, 2021

Coitus Interruptus

G.W. Bowersock, "The Art of the Footnote,"

American Scholar 53.1 (Winter 1984) 54-62 (at 54):

If the text should actually prove to be absorbing, ordinary footnotes afford no pleasure whatever. Encountering one, as Noel Coward remarked, is like going downstairs to answer the doorbell while making love.

Modesty

Poggio Bracciolini, letter to Franciscus Marescalcus of Ferrara, 1436 (tr. Phyllis Walter Goodhart Gordan):

I have never made nor do I make a great deal of my writings, for I am never so conscious of how trifling is my ability to express myself as when I take pen in hand and settle my mind on the effort of writing. In this matter I am very often such a failure in my own eyes that I seem to myself ignorant and without talent in writing since sometimes not only matter but even words fail me, although I have spent a long time searching for what I should say.

[....]

Therefore read when you find time free from more important business and, if you are offended by anything in your reading, be generous either to my ignorance or to my wordiness.

Neque enim scripta mea unquam magni feci, neque facio, tunc maxime cognoscens quam parum dicendi facultate possim, quum sumpto calamo animum ad scribendi curam accommodavi. In quo persaepe ita mihi ipsi desum, ut rudis atque ingenii inops mihi videar in scribendo, quum non solum sententiae aliquando, sed etiam verba deficiant, licet diutius quid dicam investiganti.

[....]

Leges igitur, quum tempus vacuum nactus eris a majoribus negotiis, et si qua in re inter legendum offenderis, dabis veniam vel ignorantiae, vel verbositati.

Killing and Mutilation

David West (1926-2013), The Imagery and Poetry of Lucretius (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1969), pp. 9-10:

'Imaging is, in itself', according to Dryden, 'the very height and life of poetry.' This is true of the poetry of Lucretius. Yet his images are frequently not explained by commentators and not respected by translators. Even those writing expressly on his imagery have done little more than pass general judgments supported by lists of paraphrased examples. Popular though it is among writers on classical literature, paraphrase kills poetry, and in Lucretius (where so much depends upon the acuity of the detail), it mutilates the corpse.

Thursday, July 22, 2021

War's Embrace

Homer, Iliad 17.227-228 (tr. Peter Green):

So let each man make straight for the foe, whether to perishὀαριστύς is meeting, intimate conversation, dalliance, from ὄαρ = wife.

or come safely through: that's the sweet embrace of warfare.

τώ τις νῦν ἰθὺς τετραμμένος ἢ ἀπολέσθω

ἠὲ σαωθήτω· ἣ γὰρ πολέμου ὀαριστύς.

The End of Civilization

M.L. West, "The New OCT of Sophocles," a review of Sophoclis Fabulae by H. Lloyd-Jones and N.G. Wilson (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990), and Sophoclea. Studies on the Text of Sophocles by H. Lloyd-Jones and N.G. Wilson (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990), in Classical Review 41.2 (1991)

299-301 (at 301):

Related post: The Chief Reason to Learn Latin.

An OCT with a preface in English! This is the end of civilization as we have known it.Traditionally books in the Oxford Classical Text (OCT) series had prefaces written in Latin.

Related post: The Chief Reason to Learn Latin.

Dust

Friedrich Nietzsche, Unpublished Fragments from the Period of Thus Spoke Zarathustra (Summer 1882-Winter 1883/84), tr. Paul S. Loeb and David F. Tinsley (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2019 = The Complete Works of Friedrich Nietzsche, vol. 14), pp. 394-395 (Notebook 13, number 1):

You throw dust around yourselves like sacks of grain, you scholars, and without meaning to! Still, who would have guessed that your dust comes from grain and from the golden bliss of summer fields?Friedrich Nietzsche, Nachgelassene Fragmente 1882-1884, edd. Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari, 2. Aufl. (Munich: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, 1988 = Kritische Studienausgabe, Bd. 10), p. 440:

Gleich Mehlsäcken staubt ihr um euch, ihr Gelehrten, und unfreiwillig! Doch wer erriethe, daß euer Staub her vom Korne stammt und von der gelben Wonne der Sommerfelder?

In Defence of Apathy

M.I. Finley, "Leaders and Followers," in his Democracy Ancient and Modern, 2nd ed. (London: The Hogarth Press, 1985), pp. 3-37 (at 4, with note on p. 173):

Or when Aristotle (Politics, 1319al9-38) argued that the best democracy will be in a state with a large rural hinterland and a relatively numerous population of farmers and herdsmen, who "are scattered over the country, do not meet together so often or feel the need of assembling," one feels a kinship with a contemporary political scientist, W.H. Morris Jones, who wrote, in an article with the revealing title, "In Defence of Apathy," that "many of the ideas connected with the general theme of a Duty to Vote belong properly to the totalitarian camp and are out of place in the vocabulary of liberal democracy"; that political apathy is a "sign of understanding and tolerance of human variety" and has a "beneficial effect on the tone of political life" because it is a "more or less effective counter-force to the fanatics who constitute the real danger to liberal democracy."3

3. Political Studies, 2 (1954) 25-37, at pp. 25 and 37, respectively.

Wednesday, July 21, 2021

Honest Fools and Dishonest Swindlers

Frederick Engels, "On the History of Early Christianity," in Marx and Engels, On Religion (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1975; rpt. 1981), pp. 275-300 (at 280):

And just as all those who have nothing to look forward to from the official world or have come to the end of their tether with it—opponents of inoculation, supporters of abstemiousness, vegetarians, anti-vivisectionists, nature-healers, free-community preachers whose communities have fallen to pieces, authors of new theories on the origin of the universe, unsuccessful or unfortunate inventors, victims of real or imaginary injustice who are termed "good-for-nothing pettifoggers" by all bureaucracy, honest fools and dishonest swindlers—all throng to the workers' parties in all countries—so it was with the first Christians.

Dolts

Lucretius 1.641-644 (tr. W.H.D. Rouse):

For dolts admire and love everything more

which they see hidden amid distorted words,

and set down as true whatever can prettily tickle

the ears and all that is varnished over with fine-sounding phrases.

omnia enim stolidi magis admirantur amantque,

inversis quae sub verbis latitantia cernunt,

veraque constituunt quae belle tangere possunt

auris et lepido quae sunt fucata sonore.

A Holy Thing

Martin P. Nilsson, Geschichte der griechischen Religion, 2. Aufl., Bd. I: Die Religion Griechenlands bis auf die griechische Weltherrschaft (Munich: C.H. Beck'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1965), pp. 118-119, tr. in Jeffrey Henderson, The Maculate Muse: Obscene Language in Attic Comedy, 2nd ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), p. 13, n. 30 (footnotes omitted in the German text):

Thus the phallus of the Greeks came to be regarded as a holy thing, not as a fascinum whose indecency warded off evil influences. To be sure, a belief in the efficacy of indecent gestures as countermagic did persist, but for the most part it was restricted to the female organs. In regard to the phallus and the sex act, the Greeks were as dispassionate as animal breeders, a fact demonstrated by a great multitude of vases whose illustrations are to our minds too shocking to be exhibited, to say nothing of the comic poets. The Romans, on the other hand, possessed the same feelings of modesty as we, and so for the Romans the phallus was fascinum.

So wurde der Phallos von den Griechen als ein Heiltum betrachtet, nicht als ein fascinum, dessen Unanständigkeit böse Einflüsse abwehrt. Ein Glaube an die Wirkung unanständiger Gebärden als Gegenzauber bestand allerdings, beschränkte sich aber hauptsächlich auf die weibliche Organe. Dem Phallos und dem Geschlechtsakt standen die Griechen fast ebenso unbefangen gegenüber wie Tierzüchter; das zeigen eine ganz Anzahl Vasen, die wegen ihrer für unsere Begriffe anstössigen Bilder nicht ausgestellt werden können — von den Komodiendichtern nicht zu sprechen. Die Römer dagegen besassen dieselbe Art des Schamgefühls wie wir, und bei ihnen ist der Phallos fascinum.

Classic and Romantic

Goethe, Conversations with Eckermann, April 2, 1829 (Goethe speaking; tr. John Oxenford):

I call the classic healthy, the romantic sickly. In this sense, the 'Nibelungenlied' is as classic as the 'Iliad,' for both are vigorous and healthy. Most modern productions are romantic, not because they are new, but because they are weak, morbid, and sickly; and the antique is classic, not because it is old, but because it is strong, fresh, joyous, and healthy. If we distinguish 'classic' and 'romantic' by these qualities, it will be easy to see our way clearly.

Das Klassische nenne ich das Gesunde, und das Romantische das Kranke. Und da sind die Nibelungen klassisch wie der Homer, denn beide sind gesund und tüchtig. Das meiste Neuere ist nicht romantisch, weil es neu, sondern weil es schwach, kränklich und krank ist, und das Alte ist nicht klassisch, weil es alt, sondern weil es stark, frisch, froh und gesund ist. Wenn wir nach solchen Qualitäten Klassisches und Romantisches unterscheiden, so werden wir bald im reinen sein.

Tuesday, July 20, 2021

A Loud Giant

Peter Green, The Greco-Persian Wars (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), p. 89:

Xerxes' pleasure in these harmless junketings was only marred by the sudden death, after a short illness, of his relative Artachaeës, a shambling giant (reputedly eight feet tall) with the loudest voice in Persia. This Stentorian monster, appropriately enough, had been general overseer of the canal workmen. He received a magnificent funeral, and the whole army helped to raise a great mound over his grave. By Herodotus's day the local inhabitants were already sacrificing to Artachaeës 'as to a demi-god', and invoking his name during their prayers. Why not? He had been larger, and louder, than any of them. One commentator remarks that 'respect for mere size is an Oriental characteristic', citing the Mamelukes' surprise at Napoleon's shortness; but there is something very Greek about this metamorphosis too. In the increasingly anthropocentric world of the fifth century BC — 'Man is the measure of all things', said Protagoras — nothing could have been more logical, when one comes to think of it, than to worship an outsize human being.Herodotus 7.117 (tr. Robin Waterfield):

[1] During Xerxes' stay in Acanthus Artachaees, who had been in charge of the construction of the canal, happened to die of disease. Artachaees was an Achaemenid who was very highly regarded by Xerxes; he was the tallest of the Persians (being only four fingers short of five royal cubits) and he had the loudest voice in the world. Xerxes was deeply upset at his death and gave him a magnificent funeral and burial; the whole army helped to raise his burial mound. [2] On the advice of an oracle, the people of Acanthus have instituted a hero-cult of Artachaees, which involves calling on him by name.

[1] ἐν Ἀκάνθῳ δὲ ἐόντος Ξέρξεω συνήνεικε ὑπὸ νούσου ἀποθανεῖν τὸν ἐπεστεῶτα τῆς διώρυχος Ἀρταχαίην, δόκιμον ἐόντα παρὰ Ξέρξῃ καὶ γένος Ἀχαιμενίδην, μεγάθεΐ τε μέγιστον ἐόντα Περσέων (ἀπὸ γὰρ πέντε πηχέων βασιληίων ἀπέλειπε τέσσερας δακτύλους) φωνέοντά τε μέγιστον ἀνθρώπων, ὥστε Ξέρξην συμφορὴν ποιησάμενον μεγάλην ἐξενεῖκαί τε αὐτὸν κάλλιστα καὶ θάψαι· ἐτυμβοχόεε δὲ πᾶσα ἡ στρατιή. [2] τούτῳ δὲ τῷ Ἀρταχαίῃ θύουσι Ἀκάνθιοι ἐκ θεοπροπίου ὡς ἥρωι, ἐπονομάζοντες τὸ οὔνομα.

Samizdat

M.I. Finley, "Censorship in Classical Antiquity," in his Democracy Ancient and Modern, 2nd ed. (London: The Hogarth Press, 1985), pp. 142-172 (at 146):

There is an important sense in which it is correct to say that all written works in antiquity were a kind of samizdat, not because they were always, or even usually, illicit, but because their circulation was restricted to copies prepared by hand and passed by hand from person to person.Id. (at 153-154):

It is extremely important to realize that in classical antiquity (and indeed anywhere before the invention of printing) the number of books in circulation and the number of readers of books were infinitesimal and insignificant outside the small world of professional philosophers and intellectuals. And even they relied heavily on oral communication and memory, like everyone else. Books and pamphlets played no real part in affecting or moulding public opinion, even in élite circles.

Death Speaks

Euripides, Alcestis 55 (my translation):

When those who pass away are young I gain greater honor.I.e. than he does when they are old.

νέων φθινόντων μεῖζον ἄρνυμαι γέρας.

γέρας BOV et Σbv: κλέος LP

How to Increase Strength and Flexibility

Martin L. West, "Diminishing Returns and New Challenges," in Christopher Stray et al., edd., Liddell and Scott:

The History, Methodology, and

Languages of the World's Leading

Lexicon of Ancient Greek (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), pp. 339-352 (at 340):

We older folk cannot really imagine ever managing without the ponderous physical presence of a hard-copy LSJ within reach. It has contributed not a little to the strength and suppleness of our wrists.

Sunday, July 18, 2021

Eye-Philologists

W.B. Stanford, The Sound of Greek: Studies in the Greek Theory and Practice of Euphony (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967 = Sather Classical Lectures, 38), p. 1, with notes on pp. 19-20:

In our world of printed books we mostly study and enjoy literature in silence. We do sometimes hear the sound of poetry and of good prose in the classroom and in the theatre, and when we listen to the radio. But most of our literary experience, as adults at any rate, is silent. We sit in a library or at home; our eyes move quickly over black marks on a white page; and our mind takes in an author's thoughts and images. When we were children at school, our teachers taught us to aim at rapid reading: the sooner we got through the elementary stage of sounding the words as we went along, the better, they said. In any educational book on the psychology of reading you will probably find a section called something like "Training to Decrease Vocalization."1Jespersen is Otto Jespersen, Language: Its Nature, Development, and Origin (London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd., 1922), p. 24:

We take all this for granted, and undoubtedly we gain great benefits from this silent, rapid reading. So when we are studying the classical literatures of Greece and Rome we generally aim at reading them in just the same way. We use our eyes, but not our ears and our voices.2 We are what has been aptly called "eye-philologists," not "ear-philologists."3

1 See, e.g., John Anthony O'Brien, Silent Reading (New York, 1921).

2 Cf. A.W. Verrall, The Bacchants of Euripides and Other Essays (Cambridge, 1910) 246: "The habit of silent reading has made us slow to catch the sound of what is written. And moreover, used to language and poetry constructed on principles not merely different from the Greek, but diametrically opposed, our attention, even if given to the sound, brings us no natural and instinctive report. To logic, rhetoric, pathos we are alive; and upon these heads the tragic poets are criticised; but as to noise we will not notice it, not even if we are bidden and bidden again."

3 I take the terms "eye-philologists" and "ear-philologists" from Jespersen 23 f. How little the ear counts among modern rhetoricians is exemplified in the neglect of all matters of verbal sound except rhythm in so full a manual as Cleanth Brooks and Robert Penn Warren, Modern Rhetoric (New York, 1949).

But there can be no doubt that the way in which Latin has been for centuries made the basis of all linguistic instruction is largely responsible for the preponderance of eye-philology to ear-philology in the history of our science.

One Life Only

Epicurus, Sententiae Vaticanae 14 = fragment 204 Usener (tr. Brad Inwood and L.P. Gerson):

We are born only once, and we cannot be born twice; and one must for all eternity exist no more. You are not in control of tomorrow and yet you delay your [opportunity to] rejoice. Life is ruined by delay and each and every one of us dies without enjoying leisure.Text and apparatus from P. von der Mühll, ed., Epicuri Epistulae Tres et Ratae Sententiae a Laertio Diogene Servatae...Accedit Gnomologium Epicureum Vaticanum (Leipzig: B.G. Teubner, 1922), p. 61: Cf. Jürgen Hammerstaedt and Martin Ferguson Smith, "Diogenes of Oinoanda: New Discoveries of 2012 (NF 206–212) and New Light on 'Old' Fragments," Epigraphica Anatolica 45 (2012) 1–37 (at 21 = NF 209 II, lines 3-6):

γεγόναμεν ἅπαξ, δὶς δὲ οὐκ ἔστι γενέσθαι· δεῖ δὲ τὸν αἰῶνα μηκέτι εἶναι· σὺ δὲ οὐκ ὢν τῆς αὔριον <κύριος> ἀναβάλλῃ τὸν χαῖρον· ὁ δὲ βίος μελλησμῷ παραπόλλυται καὶ εἷς ἕκαστος ἡμῶν ἀσχολούμενος ἀποθνῄσκει.

ὡϲ οὐκ ἔϲτιν

δὶϲ ἀποθανεῖν,

οὕτωϲ οὐδὲ δὶϲ

ζῆϲαι.

As it is not possible to die twice, so it is not possible to live twice either.

Saturday, July 17, 2021

A Greek Vase

5th century BC kantharos from Nola, attributed to the Amphitrite Painter (London, British Museum, Museum number 1865,0103.23, Catalogue number E155):

Some think this represents Death and Heracles fighting over Alcestis. See e.g. Herbert González Zymla, "La iconografía de Thanatos, el dios muerte en el arte griego, y la percepción de

lo macabro desde la sensibilidad clásica," Eikón Imago 10 (2021) 107-128 (at 122). But the vase isn't listed in T.B.L. Webster, Monuments Illustrating Tragedy and Satyr Play, 2nd ed. (London: University of London, Institute of Classical Studies, 1967), p. 154, under the entry for Euripides' Alcestis.

Your Thoughts and Dreams

Richard Kannicht and Bruno Snell, edd., Tragicorum Graecorum Fragmenta, Vol. 2: Fragmenta Adespota, rev. ed. (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2007), p. 53 (Adespota fr. 127, here without the lunate sigmas, followed by apparatus, testimonial and critical, from TrGF; tr. C. Bradford Welles):

Your thoughts reach higher than the air;In line 6 Welles translates Burges' conjecture ταχύπουν (accusative), rather than the manuscript reading ταχύπους (nominative).

You dream of wide fields' cultivation,

The homes you plan surpass the homes

That men have known, but you do err,

Guiding your life afar.

But one there is who'll catch the swift,

Who goes a way obscured in gloom,

And sudden, unseen, overtakes

And robs us of our distant hopes—

Death, mortals' source of many woes.

φρονεῖτε νῦν αἰθέρος ὑψηλότερον

καὶ μεγάλων πεδίων ἀρούρας,

φρονεῖθ᾿ ὑπερβαλλόμενοι

†δόμων† δόμους, ἀφροσύνᾳ

πρόσω βιοτὰν τεκμαιρόμενοι. 5

ὁ δ᾿ ἀμφιβάλλει ταχύπους

κέλευθον ἕρπων σκοτίαν,

ἄφνω δ᾿ ἄφαντος προσέβα

μακρὰς ἀφαιρούμενος ἐλ-

πίδας θνατῶν πολύμοχθος Ἅιδας 10

Friday, July 16, 2021

Extremism

Barry Baldwin, Studies in Aulus Gellius (Lawrence: Coronado Press, 1975), p. 2:

[E]xtremism in the pursuit of literacy is no vice.

Civility Pledge

Aristophanes, Lysistrata 1043-1049 (tr. Alan H. Sommerstein):

We are not preparing, gentlemen,Manfred Landfester ad loc.:

to say anything slanderous at all

about any of our fellow-citizens,

but, quite the contrary,

to say and do nothing

but good; for you've quite enough troubles

on your plates already.

οὐ παρασκευαζόμεσθα τῶν πολιτῶν οὐδέν᾽, ὦνδρες,

φλαῦρον εἰπεῖν οὐδὲ ἕν,

ἀλλὰ πολὺ τοὔμπαλιν πάντ᾽ ἀγαθὰ καὶ λέγειν

καὶ δρᾶν· ἱκανὰ γὰρ τὰ κακὰ καὶ τὰ παρακείμενα.

1043–1045 „Wir haben nicht vor, […] etwas Schlechtes (griech. phlaúron) über einen Bürger zu sagen“: Der Chor spricht im Folgenden nicht als Chor der alten Männer und Frauen der Handlung, sondern vor allem auktorial als der Dichter Aristophanes. Damit hat dieses Stasimon Elemente einer Parabase übernommen. Mit dem „nichts Schlechtes über einen Bürger sagen“ zeigt der Chor den Verzicht auf das „namentliche Verspotten“ (griech. onomastí kōmōdeín), das Markenzeichen der Alten Komödie, an.

1048f. „Schlimmes (griech. kaká) gibt es schon genug“: Es ist nicht etwas „Schlimmes“ in der Handlung der Komödie für den Chor, sondern entspre- chendt dem parabasenartigen Charakter des Liedes der „schlimme“ Zustand der Stadt Athen vor allem nach der Katastrophe der Sizilischen Expedition, den Thukydides (8,1,2) lapidar und zugleich eindrucksvoll als eine Art Schockstarre wegen des Verlustes vieler Bürger beschrieben hat.

Thursday, July 15, 2021

An Unseemly Gesture?

Herodotus 2.162.3 (tr. A.D. Godley):

Alan B. Lloyd, Herodotus, Book II, Commentary 99-182 (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1993), pp. 176-177: N.G. Wilson, Herodotea: Studies on the Text of Herodotus (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), p. 45: Favorino di Arelate, Opere. Introduzione, Testo Critico e Commento a cura di Adelmo Barigazzi (Florence: Felice Le Monnier, 1966), pp. 159-160 (fragment 15): My translation of Favorinus, fragment 15 Barigazzi:

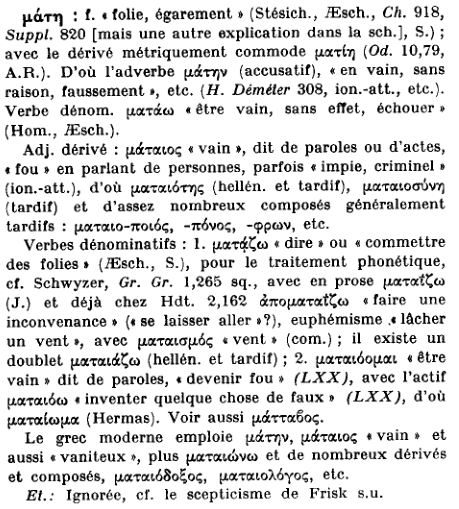

On the root of ἀποματαΐζω see Pierre Chantraine, Dictionnaire étymologique de la langue grecque, III (Paris: Klincksieck, 1974), p. 672 (s.v. μάτη):

When Apries heard of it, he sent against Amasis an esteemed Egyptian named Patarbemis, one of his own court, instructing him to take the rebel alive and bring him into his presence. Patarbemis came, and summoned Amasis, who lifted his leg with an unseemly gesture (being then on horseback) and bade the messenger take that token back to Apries.J. Enoch Powell, A Lexicon to Herodotus (Cambridge: At the University Press, 1938), p. 41, renders ἀποματαΐζω as "break wind". Similarly Franco Montanari, The Brill Dictionary of Ancient Greek (Leiden: Brill, 2015), p. 260, s.v. ἀποματαΐζω: "to break wind (euphem. for ἀποπέρδω)". Cf. The Cambridge Greek Lexicon, Vol. I: A-I (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021), p. 190, s.v. ἀποματαΐζω: "respond in an insulting way (app. w. a fart)".

πυθόμενος δὲ ταῦτα ὁ Ἀπρίης ἔπεμπε ἐπ᾽ Ἄμασιν ἄνδρα δόκιμον τῶν περὶ ἑωυτὸν Αἰγυπτίων, τῷ οὔνομα ἦν Πατάρβημις, ἐντειλάμενος αὐτῷ ζῶντα Ἄμασιν ἀγαγεῖν παρ᾽ ἑωυτόν. ὡς δὲ ἀπικόμενος τὸν Ἄμασιν ἐκάλεε ὁ Πατάρβημις, ὁ Ἄμασις, ἔτυχε γὰρ ἐπ᾽ ἵππου κατήμενος, ἐπάρας ἀπεματάϊσε, καὶ τοῦτό μιν ἐκέλευε Ἀπρίῃ ἀπάγειν.

Alan B. Lloyd, Herodotus, Book II, Commentary 99-182 (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1993), pp. 176-177: N.G. Wilson, Herodotea: Studies on the Text of Herodotus (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), p. 45: Favorino di Arelate, Opere. Introduzione, Testo Critico e Commento a cura di Adelmo Barigazzi (Florence: Felice Le Monnier, 1966), pp. 159-160 (fragment 15): My translation of Favorinus, fragment 15 Barigazzi:

A man from Boeotia, seventy years old, happening upon a treasure, lifted his leg, farted, and passed by, as if it no longer meant anything to him. So it is that old age puts an end at the same time to both avarice and curiosity.Text and translation of the fragment of Favorinus can also be found in Denis M. Searby, The Corpus Parisinum. A Critical Edition of the Greek Text with Commentary and English Translation. A Medieval Anthology of Greek Texts from the Pre-Socratics to the Church Fathers, 600 B.C. - 700 A.D. (Lewiston: The Edwin Mellen Press, 2007), pp. 288 and 671.

Ὁ Βοιωτὸς ἐντυχὼν θησαυρῷ µετὰ ἑβδοµήκοντα ἔτη ἐπάρας τὸ σκέλος ἀπεµατάισε καὶ παρῆλθεν, ὡς οὐκέτι οὐδὲν ὄντα πρὸς αὐτόν. ὥστε καὶ πολυχρηματίας ἅµα παύει τὸ γῆρας καὶ πολυπραγµοσύνης.

On the root of ἀποματαΐζω see Pierre Chantraine, Dictionnaire étymologique de la langue grecque, III (Paris: Klincksieck, 1974), p. 672 (s.v. μάτη):

Labels: noctes scatologicae

A Fine Number

Robert E. Lee, letter to his son George Washington Custis Lee, then a cadet at West Point (February 1, 1852), concerning upcoming examinations in June, quoted in Douglas Southall Freeman, R.E. Lee: A Biography, Vol. I (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1943), p. 312:

Removal of the statue of Robert E. Lee and his horse Traveller from Market Street Park (formerly Lee Park) in Charlottesville, Virginia, on July 10, 2021:

You must be No. 1. It is a fine number. Easily found and remembered. Simple and unique. Jump to it fellow.This reminds me of Homer's αἰὲν ἀριστεύειν καὶ ὑπείροχον ἔμμεναι ἄλλων (Iliad 6.208 and 11.784), translated by Peter Green as "always to be the best, preeminent over others."

Removal of the statue of Robert E. Lee and his horse Traveller from Market Street Park (formerly Lee Park) in Charlottesville, Virginia, on July 10, 2021:

Inconveniences

Thomas Jefferson, letter to Archibald Stuart (December 23. 1791):

I would rather be exposed to the inconveniences attending too much liberty than to those attending too small a degree of it.

Stopgap

Friedrich Nietzsche, Unpublished Fragments from the Period of Thus Spoke Zarathustra (Summer 1882-Winter 1883/84), tr. Paul S. Loeb and David F. Tinsley (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2019 = The Complete Works of Friedrich Nietzsche, vol. 14), p. 382 (Notebook 13, number 1):

And there, where your understanding has sprung a leak, you quickly stick the poorest of all plugs: his name is "God."Friedrich Nietzsche, Nachgelassene Fragmente 1882-1884, edd. Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari, 2. Aufl. (Munich: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, 1988 = Kritische Studienausgabe, Bd. 10), p. 427:

Und wo euer Verstand eine Lücke hat, da stellt ihr flugs den ärmsten aller Lückenbüßer hinein: „Gott“ ist sein Name.

Wednesday, July 14, 2021

Error Prevails

Goethe, Conversations with Eckermann, December 16, 1828 (Goethe speaking; tr. John Oxenford):

The truth must be repeated over and over again, because error is repeatedly preached among us, not only by individuals, but by the masses. In periodicals and cyclopædias, in schools and universities; everywhere, in fact, error prevails, and is quite easy in the feeling that it has a decided majority on its side.

Und denn, man muß das Wahre immer wiederholen, weil auch der Irrtum um uns her immer wieder geprediget wird, und zwar nicht von einzelnen, sondern von der Masse. In Zeitungen und Enzyklopädien, auf Schulen und Universitäten, überall ist der Irrtum obenauf, und es ist ihm wohl und behaglich, im Gefühl der Majorität, die auf seiner Seite ist.

The Nature of the Gods

Lucretius 1.44-49 = 2.646-651 (tr. W.H.D. Rouse):

For the very nature of divinity must necessarilyEpicurus, Principal Doctrines 1 (tr. Cyril Bailey):

enjoy immortal life in the deepest peace,

far removed and separated from our troubles;

for without any pain, without danger,

itself mighty by its own resources, needing us not at all,

it is neither propitiated with services nor touched by wrath.

omnis enim per se divum natura necessest

immortali aevo summa cum pace fruatur

semota ab nostris rebus seiunctaque longe;

nam privata dolore omni, privata periclis,

ipsa suis pollens opibus, nihil indiga nostri,

nec bene promeritis capitur nec tangitur ira.

The blessed and immortal nature knows no trouble itself nor causes trouble to any other, so that it is never constrained by anger or favour. For such things exist only in the weak.Cicero, On the Nature of the Gods 1.17.45a (tr. H. Rackham):

τὸ μακάριον καὶ ἄφθαρτον οὔτε αὐτὸ πράγματα ἔχει οὔτε ἄλλῳ παρέχει· ὥστε οὔτε ὀργαῖς οὔτε χάρισι συνέχεται· ἐν ἀσθενεῖ γὰρ πᾶν τὸ τοιοῦτον.

If this is so, the famous maxim of Epicurus truthfully enunciates that 'that which is blessed and eternal can neither know trouble itself nor cause trouble to another, and accordingly cannot feel either anger or favour, since all such things belong only to the weak.'See Cyril Bailey, The Greek Atomists and Epicurus: A Study (1928; rpt. New York: Russell & Russell, 1964), pp. 472-473.

quod si ita est, vere exposita illa sententia est ab Epicuro, quod beatum aeternumque sit id nec habere ipsum negotii quicquam nec exhibere alteri, itaque neque ira neque gratia teneri, quod, quae talia essent, inbecilla essent omnia.

Personal Investigation

Polybius 12.27.4-6 (tr. Ian Scott-Kilvert):

[4] You can busy yourself among books with very little danger or hardship, provided only that you have taken care to have access to a city which is well supplied with records or to have a library close at hand. [5] After that you need only pursue your researches while reclining on your couch, and you can compare the mistakes of earlier historians without undergoing any hardship. [6] Personal investigation, on the other hand, demands much greater exertion and expense, but it is of prime importance and makes the greatest contribution of all to history.Günter Glockmann and Hadwig Helms, Polybios-Lexikon, Bd. II, Lieferung 2 (Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 2005), col. 501 (s.v. πολυπραγμοσύνη):

[4] τὰ μὲν ἐκ τῶν βυβλίων δύναται πολυπραγμονεῖσθαι χωρὶς κινδύνου καὶ κακοπαθείας, ἐάν τις αὐτὸ τοῦτο προνοηθῇ μόνον ὥστε λαβεῖν ἢ πόλιν ἔχουσαν ὑπομνημάτων πλῆθος ἢ βυβλιοθήκην που γειτνιῶσαν. [5] λοιπὸν κατακείμενον ἐρευνᾶν δεῖ τὸ ζητούμενον καὶ συγκρίνειν τὰς τῶν προγεγονότων συγγραφέων ἀγνοίας ἄνευ πάσης κακοπαθείας. [6] ἡ δὲ πολυπραγμοσύνη πολλῆς μὲν προσδεῖται ταλαιπωρίας καὶ δαπάνης, μέγα δέ τι συμβάλλεται καὶ μέγιστόν ἐστι μέρος τῆς ἱστορίας.

Tuesday, July 13, 2021

Can't Live With 'Em or Without 'Em

Aristophanes, Lysistrata 1038-1039 (tr. Jeffrey Henderson):

That ancient adage is right on the mark and no mistake:Commentators cite [Susarion], fragment 1 (tr. Ian C. Storey):

"Can't live with the pests or without the pests either."

κἄστ᾿ ἐκεῖνο τοὔπος ὀρθῶς κοὐ κακῶς εἰρημένον,

οὔτε σὺν πανωλέθροισιν οὔτ᾿ ἄνευ πανωλέθρων.

Listen, people, Susarion has this to say,R. Kassel and C. Austin, edd., Poetae Comici Graeci, Vol. VII: Menecrates — Xenophon (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1989), pp. 664-665: See also S. Douglas Olson, Broken Laughter. Select Fragments of Greek Comedy. Edited with Introduction, Commentary, and Translation (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), pp. 321, 328-330, 458.

the son of Philinus, from Tripodisce in Megara:

women are a bad thing, but nevertheless, my townsfolk,

you cannot have a home without a bad thing.

Both to marry and not to marry is a bad thing.

ἀκούετε λεῴ· Σουσαρίων λέγει τάδε

υἱὸς Φιλίνου Μεγαρόθεν Τριποδίσκιος.

κακὸν γυναῖκες· ἀλλ᾿ ὅμως, ὦ δημόται,

οὐκ ἔστιν οἰκεῖν οἰκίαν ἄνευ κακοῦ.

καὶ γὰρ τὸ γῆμαι καὶ τὸ μὴ γῆμαι κακόν.

Monday, July 12, 2021

Are We Defenseless?

Friedrich Schiller, William Tell, lines 644-646 (from Act I, Scene 4; my translation):

Are we then defenseless? To what purpose did we learn

The crossbow to draw and the heavy weight

Of the battle axe to swing?

Sind wir denn wehrlos? Wozu lernten wir

Die Armbrust spannen und die schwere Wucht

Der Streitaxt schwingen?

Akin and Alike

Aristotle, Rhetoric 1.11.25 (1371 b 12-17; tr. John Henry Freese, with his notes):

And since that which is in accordance with nature is pleasant, and things which are akin are akin in accordance with nature, all things akin and like are for the most part pleasant to each other, as man to man, horse to horse, youth to youth. This is the origin of the proverbs:William M.A. Grimaldi ad loc.: Related posts:The old have charms for the old, the young for the young,and all similar sayings.

Like to like,a

Beast knows beast,

Birds of a feather flock together,b

a Odyssey, xvii.218 ὡς αἰεὶ τὸν ὁμοῖον ἄγει θεὸς ὡς τὸν ὁμοῖον.

b Literally, “ever jackdaw to jackdaw.”

καὶ ἐπεὶ τὸ κατὰ φύσιν ἡδύ, τὰ συγγενῆ δὲ κατὰ φύσιν ἀλλήλοις ἐστίν, πάντα τὰ συγγενῆ καὶ ὅμοια ἡδέα ὡς ἐπὶ τὸ πολύ, οἷον ἄνθρωπος ἀνθρώπῳ καὶ ἵππος ἵππῳ καὶ νέος νέῳ, ὅθεν καὶ αἱ παροιμίαι εἴρηνται, ὡς "ἧλιξ ἥλικα τέρπει", καὶ "ὡς αἰεὶ τὸν ὁμοῖον", καὶ "ἔγνω δὲ θὴρ θῆρα", "καὶ γὰρ κολοιὸς παρὰ κολοιόν", καὶ ὅσα ἄλλα τοιαῦτα.

Every One Can Draw

Douglas Southall Freeman, R.E. Lee: A Biography, Vol. I (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1943), p. 63 (on the curriculum at West Point; footnote omitted):

The one added academic study was free-hand drawing of the human figure. This was under the tutelage of Thomas Gimbrede, an amiable Frenchman, a good miniaturist, and a competent engraver, who was not altogether without the blessed quality of humor. It was Mr. Gimbrede's custom to give each class of beginners an introductory lecture, in the course of which he endeavored to prove to unbelieving third-classmen that every one could learn to draw. His proof was: "There are only two lines in drawing, the straight line and the curve line. Every one can draw a straight line and every one can draw a curve line — therefore, every one can draw."

Sunday, July 11, 2021

A Great Corrupter

Andrew Robert Burn (1902-1991), Persia and the Greeks: The Defence of the West, 546-478 B.C. (1962; rpt. Totowa: Minerva Press, 1968), pp. 6-7:

Tradition is a great corrupter. It may preserve important facts, though even then the preservation may take the form of seizing on one important or merely picturesque fact and embroidering it. Einhard tells us that Hrodland, Count of the Breton Marches, was killed by the Basques in an attack on the rearguard of Charlemagne's army returning from Spain; three hundred years later, Roland is the hero of a mighty epic, falling after tremendous slaughter before a huge host of Saracens, and avenged by the destruction of all the hosts of Babylon by his lord (who a few weeks earlier, with Roland to help him, had been unable to capture Pampeluna). Why Roland became the hero of the great poem, we may perhaps guess when we remember what was Roland's most famous attribute: a horn; and what was famous about the horn: that, at the crisis of his fortunes, he refused to blow it. Did the real Count Hrodland refuse to call for help and stop the main column in a defile, for an attack by these barbarians? If so, for his gallantry and pride he paid with his life. This is exactly the kind of thing that seizes the imagination of mankind; but it constitutes a warning against expecting popular tradition to preserve reliable history for long periods.

Compassion

Friedrich Nietzsche, Unpublished Fragments from the Period of Thus Spoke Zarathustra (Summer 1882-Winter 1883/84), tr. Paul S. Loeb and David F. Tinsley (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2019 = The Complete Works of Friedrich Nietzsche, vol. 14), p. 374 (Notebook 13, number 1):

See him, how he swells and overflows with compassion for everything that is called human: his mind is already completely drunk with compassion; soon he will be doing incredibly foolish things.Friedrich Nietzsche, Nachgelassene Fragmente 1882-1884, edd. Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari, 2. Aufl. (Munich: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, 1988 = Kritische Studienausgabe, Bd. 10), p. 419:

Seht ihn, wie er schwillt und überschwillt von Mitleiden mit allem, was Mensch heißt: ganz schon ist sein Geist ertrunken in seinem Mitleiden; bald wird er große Thorheiten thun.

Sine Qua Non

Maximianus, Elegies 5.111-116 (tr. A.M. Juster):

Related post: The Best Part of a Man.

It makes the human race, the herds, the birds, the beastsThe antecedent of the pronouns haec and hac is mentula (prick).

and everything that breathes throughout the world.

Without it there's no union of the different sexes;

the highest grace of marriage dies without it.

It brings together coupled minds with its strong bond

so that the pair combine to be one flesh.

haec genus humanum, pecudum, volucrumque, ferarum

et quicquid toto spirat in orbe, creat

hac sine diversi nulla est concordia sexus,

hac sine coniugii gratia summa perit.

haec geminas tanto constringit foedere mentes,

unius ut faciat corporis esse duo.

Related post: The Best Part of a Man.

Saturday, July 10, 2021

Enlightenment

Lucretius 1.1114-1117 (tr. Cyril Bailey):

These things you will learn thus, led on with little trouble; for one thing after another shall grow clear, nor will blind night snatch away your path from you, but that you shall see all the utmost truths of nature: so shall things kindle a light for others.H.A.J. Munro, ed., Titi Lucreti Cari De Rerum Natura Libri Sex, Vol. II (1864; rpt. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), p. 37:

haec sic pernosces parva perductus opella;

namque alid ex alio clarescet nec tibi caeca 1115

nox iter eripiet, quin ultima naturai

pervideas: ita res accendent lumina rebus.

1114 sic codd.: sei Munro

cetera iam poteris per te tute ipse videre post 1114 add. Munro

1114 sei Ed. after Nic. Nicc. Flor. 31 Camb. etc. for sic: a verse is here lost which I feel sure was of this kind, Cetera iam poteris per te tute ipse videre, with which the preceding words parva perductus opella must be joined. Lucr. says it is hard to master his principles, but when that is thoroughly done, then led on with little trouble you may learn the rest yourself. Comp. especially I 400—417, and see Camb. Journ. of phil. i p. 374. Lach. for sic reads scio and perdoctus for perductus, and then gets no satisfactory sense: Junt. reads non for nec in 1115 : Lamb. perfunctus for perdoctus: Bern. sis, and perdoctus after Lach.

Friday, July 09, 2021

Country and City

Varro, De Re Rustica 3.1.4 (tr. William Davis Hooper, rev. Harrison Boyd Ash):

It was divine nature which gave us the country, and man's skill that built the cities.

divina natura dedit agros, ars humana aedificavit urbes.

How Did Things Get Like This?

Andrew Robert Burn (1902-1991), Persia and the Greeks: The Defence of the West, 546-478 B.C. (1962; rpt. Totowa: Minerva Press, 1968), p. 3:

History represents an attempt to answer the question, 'How did things get like this?' — and the question is often stimulated by a sense that the world has gone wrong.

Thursday, July 08, 2021

Like Is Dear to Like

Theocritus, Idylls 9.31-32 (tr. A.F.S. Gow):

Cicada is dear to cicada, ant to ant, hawk to hawk...Related posts:

τέττιξ μὲν τέττιγι φίλος, μύρμακι δὲ μύρμαξ,

ἴρηκες δ᾿ ἴρηξιν...

Firsthand Experience

Polybius 12.25g.1-3 (tr. Ian Scott-Kilvert):

It is in fact equally impossible for a man who has had no experience of action in the field to write well about military operations as it is for a man who has never engaged in political affairs and their attendant circumstances to write well on those topics. And since the writings of mere book-worms lack both firsthand experience and any vividness of presentation, their work is completely without value for its readers. For if you remove from history the element of practical instruction, what is left is insignificant and without any benefit to them. Again, when writers try to provide details about cities and places without possessing firsthand experience of this kind, the result is bound to be very similar, since they will leave out many things which ought to be mentioned and deal at great length with other details which are not worth the trouble.Id., 12.25h.5-6:

For this reason the writers of the past believed that historical memoirs should possess such vividness that they would make the reader exclaim whenever the narrative dealt with political events that the author must have taken part in politics and had experience of public affairs; or when he dealt with war that he had known active service and risked his life; or when he turned to domestic matters that he had lived with a wife and brought up children, and similarly with the various other aspects of life. Now this quality can only be found in the writing of those who have played some part in affairs themselves and made this aspect of history their own. Of course it is diffcult to have been personally involved and played an active role in every kind of event, but it is certainly necessary to have had experience of the most important and those of most frequent occurrence.

Searching After Treasures

Henry Fielding, "The Covent-Garden Journal," No. 10 (February 4, 1752), in his Works, Vol. 12 (London: J.M. Dent & Co., 1902), pp. 220-225 (at 222-223):

When we are employed in reading a great and good author, we ought to consider ourselves as searching after treasures, which, if well and regularly laid up in the mind, will be of use to us on sundry occasions in our lives. If a man, for instance, should be overloaded with prosperity or adversity (both of which cases are liable to happen to us), who is there so very wise, or so very foolish, that, if he was a master of Seneca and Plutarch, could not find great matter of comfort and utility from their doctrines?

Wednesday, July 07, 2021

Country versus City Life

Martial 1.55 (tr. Walter C.A. Ker):

If you wish briefly to learn your Marcus' wishes, Fronto, bright ornament of war and of the gown, he seeks this — to be tiller of land that is his own, though not large; and rough ease he delights in amid small means. Does any man court halls gaudy and chill with Spartan stone, and bring with him — O fool! —the morning salute, who, blest with spoils of wood and field, can before his hearth open his crowded nets, and draw with trembling line the leaping fish, and bring forth from the red jar his golden honey? For whom the bailiff's portly dame loads his rickety table, and charcoal unbought cooks his home-laid eggs? May he, I pray, who loves not me love not this, and live, pale-faced, amid the duties of the town.Ludwig Friedlaender ad loc. (SG = his Sittengeschichte Roms):

Vota tui breviter si vis cognoscere Marci,

clarum militiae, Fronto, togaeque decus,

hoc petit, esse sui nec magni ruris arator,

sordidaque in parvis otia rebus amat.

quisquam picta colit Spartani frigora saxi 5

et matutinum portat ineptus have,

cui licet exuviis nemoris rurisque beato

ante focum plenas explicuisse plagas

et piscem tremula salientem ducere saeta

flavaque de rubro promere mella cado? 10

pinguis inaequales onerat cui vilica mensas

et sua non emptus praeparat ova cinis?

non amet hanc vitam quisquis me non amat, opto,

vivat et urbanis albus in officiis.

2. Fronto. Welcher Fronto hier gemeint ist, lässt sieh nicht bestimmen. Borghesi hielt ihn für S. Octavius Fronto, cos. 86, Statthalter von Mösien 92, oder für Q. Pactumeius Fronto, cos. 80. Oeuvres III 3S2, SG III 432. Mommsen (Ind. Plin.) hat an T. Catius (Caesius) Fronto, cos. 96 (10. Oktober) gedacht.On the identity of Fronto here see Juan Fernández Valverde in Rosario Moreno Soldevila et al., A Prosopography to Martial's Epigrams (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2019), pp. 239-240:

3. M. besass jedoch damals bereits sein Nomentanum (XIII 42 XIII 119). Aber es war zu dürftig, um ihn zu ernähren, SG III 397, 4.

4. Sordida. Zu I 49, 28.

5. picta Spartani frigora saxi d. h. ein mit Säulen und Wänden von grünem lakonischen Marmor (Serpentin, Marquardt Prl. 603, 13) prangendes vornehmes Atrium.

6. d. h. stattet als Client den vorgeschriebenen Morgenbesuch (salutatio) bei dem Patron ab.

ineptus. Weil diese Bemühungen für die Patrone lästig waren, überdies meist erfolglos blieben. SG I 3H8 ff.

9. tremula — saeta. Saeta für Angelschnur auch X 30, 16. Tremula linea III 58, 27.

14. albus. Von der ungesunden Blässe der Städter. SG I 32 und zu III 58, 24. Bei urbana officia ist vorzugsweise au Clientendienste zu denken.

The Vandal Epigram

D.R. Shackleton Bailey, ed., Anthologia Latina, I: Carmina in Codicibus Scripta, Fasc. 1: Libri Salmasiani Aliorumque Carmina (Stuttgart: B.G. Teubner, 1982), p. 201 (number 279):

Eric Thomson suggests (via email):

De conviviis barbarisId., p. 202 (number 280):

Inter 'eils' Goticum 'scapia matzia ia drincan'

non audet quisquam dignos edicere versus.

1 'Massmannus in Hauptii annal. german. I, p. 379 sqq. eils salutem, skapja procuratorem peni vel skap "procura, praebe", jah matjan jah drigkan "et cibum et potum" interpretatur Riese

2 audit A educere sched. : anne ded- ? uersos A

Calliope madido trepidat se iungere Baccho,Magnús Snædal, "The 'Vandal' Epigram," Filologia Germanica/Germanic Philology 1 (2009) 181-213, regards 279-280 as one poem and translates the Latin thus (at 184):

ne pedibus non stet ebria Musa suis.

Separavit L. Mueller 2 sobria idem : deb- Peiper

On foreign guests.Snædal identifies the foreign words as Vandal and interprets them as follows (at 205):

Among the Gothic 'eils scapia matzia ia drincan'

No one ventures to recite decent verses.

Calliope hurries to depart from the wet Bacchus,

So it does not happen that a drunken muse doesn't stand on her feet.

eils! scapia! matzia ia drincan!Snædal on the Sitz im Leben (at 210):

Hails! *Skapja! *Matja jah *drigkan!

'Hail! Waiter! Food and drink!'

The simplest assumption is that the author had himself tried — with limited success — to recite poetry among drunken Vandals, had witnessed such an attempt, or had been told about one. He composed the epigram about this and, although it is presented as a general truth, most likely he had a certain incident in mind. He is not making fun of Vandal poetry but only saying that dignified verses cannot been [sic, i.e. be] read while they are always ordering food and drink because Calliope flees from there. This is indeed all we can say with some certainty about the occasion of the epigram.See also Yuri Kleiner, "Another hypothesis concerning the grammar and meaning of Inter eils goticum," NOWELE: North-Western European Language Evolution 71.2 (2018) 236–248, who glosses scapia as the 1st person singular of the verb corresponding to Gothic skapjan 'make'.

Eric Thomson suggests (via email):

...the 'pedes' are both anatomical and metrical. Alcohol plays havoc with the diction, making 'dignos edicere versus' impossible (cf. Martial's tipsy Terpsichore: quid dicta nescit saucia Terpsichore, 3.68.6), so I would take 'non quisquam' as 'no one' among those doing the 'drincan'...

Tuesday, July 06, 2021

Saviors?

Friedrich Nietzsche, Unpublished Fragments from the Period of Thus Spoke Zarathustra (Summer 1882-Winter 1883/84), tr. Paul S. Loeb and David F. Tinsley (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2019 = The Complete Works of Friedrich Nietzsche, vol. 14), p. 333 (Notebook 10, number 34):

Redeemers? I call you the ones who bind and tame!Friedrich Nietzsche, Nachgelassene Fragmente 1882-1884, edd. Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari, 2. Aufl. (Munich: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, 1988 = Kritische Studienausgabe, Bd. 10), p. 374:

Erlöser? Binder und Bändiger nenne ich euch!

Martial 5.20

Martial 5.20 (tr. D.R. Shackleton Bailey, with his notes):

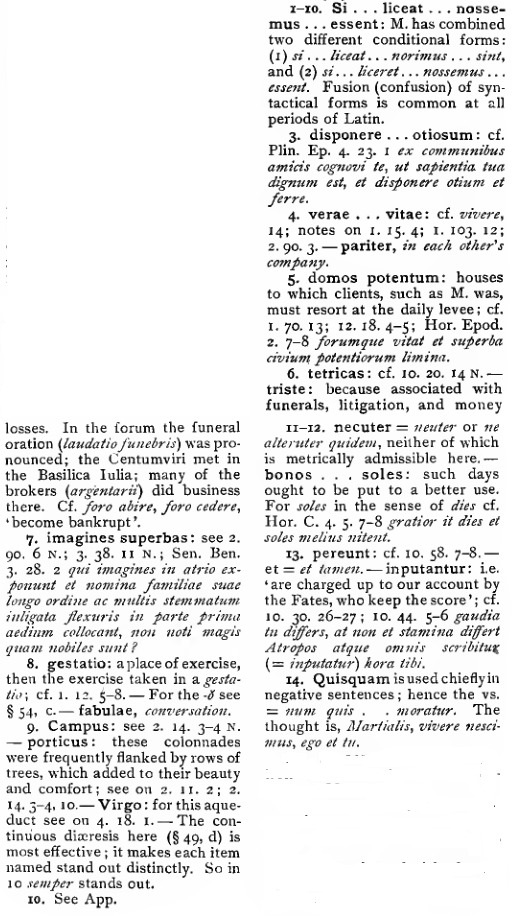

Could but you and I, dear Martialis, enjoy carefree days and dispose our time in idleness, and both alike have leisure for true living, we should know nothing of the halls and mansions of the mighty, nor sour lawsuits and the gloomy Forum, nor haughty deathmasks: but riding,a chatting, books, the Field, the colonnade,b the shade, the Virgin,c the baths — these should be our daily haunts, these our labors. As things are, neither of us lives for himself. We feel our good days slip away and leave us; they are wasted, and put to our account. Does any man, knowing the way to live, defer it?Edwin Post ad loc.: Peter Howell ad loc.:

a Gestatio also covers conveyance in a carriage or litter.

b There were several; cf. 11.1.9-12.

c Aqueduct.

Si tecum mihi, care Martialis,

securis liceat frui diebus,

si disponere tempus otiosum

et verae pariter vacare vitae,

nec nos atria nec domos potentum 5

nec litis tetricas forumque triste

nossemus nec imagines superbas;

sed gestatio, fabulae, libelli,

campus, porticus, umbra, Virgo, thermae,

haec essent loca semper, hi labores. 10

nunc vivit necuter sibi, bonosque

soles effugere atque abire sentit,

qui nobis pereunt et imputantur.

quisquam vivere cum sciat, moratur?

11 necuter sibi Schneidewin: nec ut eius ibo γ: neuter sibi β

A Renegade to the True Muse

Robert Graves, "The Virgil Cult," Virginia Quarterly Review 38.1 (Winter 1962) 13-35

(at 14):

Why Virgil's poems have for the last two thousand years exercised so great an influence on our Western culture is, paradoxically, because he was a renegade to the true Muse. His pliability; his subservience; his narrowness; his denial of that stubborn imaginative freedom which the true poets who preceded him had prized; his perfect lack of originality, courage, humour, or even animal spirits: these were the negative qualities which first commended him to government circles, and have kept him in favour ever since.

Solidarity

Cicero, De Finibus 5.23.65 (tr. H. Rackham):

Newer› ‹Older