Friday, September 30, 2022

Fall Views from the Northeast Kingdom

No Way

An Anthology of Sanskrit Court Poetry: Vidyākara's "Subhāṣitaratnakoṣa" translated by Daniel H.H. Ingalls (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1965 = Harvard Oriental Series, 44), p. 482 (number 1658):

There is no way to satisfyRelated posts:

everyone on earth;

so always see to your own good.

What harm if others talk?

Epitaph of an Ostler

Reinhold Merkelbach and Josef Stauber, Steinepigramme aus dem griechischen Osten, Bd. I: Die Westküste Kleinasiens von Knidos bis Ilion (Stuttgart; B.G. Teubner, 1998), p. 252, number 02/09/32, from Aphrodisias (simplified):

From Kevin Muse:

Θησσεὺς κτηνείτης ὁ λαλούμενος ἐνθ[ά]δε κεῖται,Translation by Joyce Reynolds et al., Inscriptions of Aphrodisias (2007):

ὅς πάσης ἀρετῆς ὢν ἀκροδικαιότερος·

ὦ παροδεῖτα, μή με παρέλθῃς

πρίν σε μαθεῖν στήλης τὰ γεγραμμένα·

ὡς ζῇς εὐφραίνου ἔσθιε πεῖνε τρύφα περιλάμβανε·

τοῦτο γὰρ ἦν τὸ τέλος [...] χρησάμενος.

Theseus the ostler, much-talked of, lies here,I don't have access to the discussion in Louis Robert, Hellenica: recueil d'épigraphie de numismatique et d'antiquités grecques, Vol. XIII, D'Aphrodisias à la Lycaonie (Paris: Librairie d'Amérique et d'Orient, Adrien-Maisonneuve, 1965), pp. 184-192. On κτηνείτης see Thomas Drew-Bear, "Some Greek Words: Part I," Glotta 50.1/2 (1972) 61-96 (at 81-82).

who, being a man of every virtue, was most particularly just.

Oh passerby, do not pass me by before you have learnt what is written on the stele.

Make merry, eat, drink, get possession of luxuries;

for this (the tomb) was the end.

From Kevin Muse:

This line of the epitaph:ὡς ζῇς εὐφραίνου ἔσθιε πεῖνε τρύφα περιλάμβανε·is translated in Reynolds et al., which you quote, as:Make merry, eat, drink, get possession of luxuries;The translation suggests that τρύφα is a (non-existent) noun meaning "luxuries" and direct object of περιλάμβανε. I think rather that τρύφα is simply the imperative of τρυφάω: luxuriate! περιλαμβάνω can simply mean "embrace." I haven't found any parallels for the use without an object, but the sense is clear enough—this is an injunction to have sex, at the climax of a series of hedonistic imperatives. Besides, I don't think it is in the spirit of the οstler's injunction for readers to busy themselves with getting possession of anything, since in death no one can take possessions with them, and the business of getting also takes one away from the business of immediate enjoyment....

Here's a parallel, suggesting even a formulaic order of actions in both inscriptions:SEG 35:1406 Pisidia

πολυκηδέα θυμόν· /

πεῖνε, τρύφα, τέρπου δώρο̣ις

χρυσῆς Ἀφροδείτης· /

Expulsion of Foreigners from Rome

J.P.V.D. Balsdon, Romans and Aliens (London: Duckworth, 1979), pp. 98-99, with notes on p. 276:

There were two occasions when, to our knowledge, foreigners were expelled at the outbreak of war. In 171 BC war had not in fact been declared against Macedon, and Macedonian envoys were in Rome trying to dispel the Senate's suspicion of king Perseus of Macedon, particularly its suspicion that Perseus had engineered the recent unsuccessful attempt on the Pergamene king Eumenes' life at Delphi. They had no success. They were ordered to leave Rome before night and to be out of Italy within thirty days; and the order was extended to cover all Macedonian residents in Rome, of whom, surprisingly, there seems to have been a number. Appian gives a graphic account of their dilemma. How were they to collect their possessions in the time? How were they to find transport? 'Some threw themselves on the ground at the city gates with their wives and children.'7Related posts:

In AD 9 there was hysteria in Rome on the news of the annihilation of three Roman legions under Varus in the Teutoberg forest in Germany. The emperor's German bodyguard was disbanded and its members removed to the islands (from which they were recalled before very long to resume their duties); 'Gauls and Celts' living or staying in Rome were ordered out of the city.8

7. P. 27, 6; L. 42, 48, 3; App., Mac. 11, 9.

8. CD 56, 23, 4; Suet., DA 49, 1 (but cf. TA 1, 24, 3). The German imperial guard was eventually disbanded by Galba, Suet., Galb. 12, 2.

What Is Life?

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, letter to Robert Southey (December 31, 1801):

We all "die daily." Heaven knows that many and many a time I have regarded my talents and requirements as a porter's burthen, imposing on me the capital duty of going on to the end of the journey, when I would gladly lie down by the side of the road, and become the country for a mighty nation of maggots. For what is life, gangrened, as it is with me, in its very vitals, domestic tranquillity?Hat tip: Eric Thomson, who remarks:

Earl Leslie Griggs, ed., Collected Letters of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Vol. II: 1801-1806, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1956), p. 427 makes no mention of it, and it isn't absolutely clear, but I wouldn't be surprised if the mention of 'maggots' and 'porter's burthen' in the letter didn't spring from a memory of Samuel Butler, Hudibras, Part 2, Canto 3 (see lines 378, 389):Beside all this, he serv'd his master

In quality of poetaster;

And rhimes appropriate could make

To ev'ry month i' th almanack 360

What terms begin and end could tell,

With their returns, in doggerel;

When the exchequer opes and shuts,

And sowgelder with safety cuts

When men may eat and drink their fill, 365

And when be temp'rate, if they will;

When use and when abstain from vice,

Figs, grapes, phlebotomy, and spice.

And as in prison mean rogues beat

Hemp for the service of the great, 370

So WHACHUM beats his dirty brains,

T' advance his master's fame and gains

And, like the Devil's oracles,

Put into doggrel rhimes his spells,

Which, over ev'ry month's blank page 375

I' th' almanack, strange bilks presage.

He would an elegy compose

On maggots squeez'd out of his nose;

In lyrick numbers write an ode on

His mistress, eating a black-pudden: 380

And when imprison'd air escap'd her,

It puft him with poetic rapture.

His sonnets charm'd th' attentive crowd,

By wide-mouth'd mortal troll'd aloud,

That 'circl'd with his long-ear'd guests, 385

Like ORPHEUS look'd among the beasts.

A carman's horse could not pass by,

But stood ty'd up to poetry:

No porter's burthen pass'd along,

But serv'd for burthen to his song. 390

Wednesday, September 28, 2022

A Short Greek Inscription

Friedrich Karl Dörner, ed., Tituli Bithyniae linguis Graeca et Latina conscripti: Paeninsula Bithynica praeter Calchedonem, Nicomedia et Ager Nicomedensis cum septemtrionali meridianoque litore Sinus Astaceni et cum Lacu Sumonensi (Vienna: Academia Scientiarum Austriaca, 1978 = Tituli Asiae Minoris, Vol. IV, Fasc. 1), number 324 (non vidi, my translation):

As long as you live, drink.A. Geoffrey Woodhead, Journal of Hellenic Studies 101 (1981) 226:

ὡς ζῆς, πῖ.

At the end of the day, after so comprehensive a reminder of mortality, one may well feel that the message of the shortest of them all, no. 324, is also the best— ὡς ζῆς, πῖ.

Afraid to Speak

Tacitus, Annals 4.69.3 (28 A.D.; tr. A.J. Woodman):

At no other time was the community more tense and panicked, behaving most cautiously of all toward those closest to them: encounters, dialogues, familiar and unfamiliar ears were avoided; even dumb and inanimate objects such as a roof and walls were treated with circumspection.A.J. Woodman ad loc:

non alias magis anxia et pavens civitas, <cautissime> agens adversum proximos; congressus, conloquia, notae ignotaeque aures vitari; etiam muta atque inanima, tectum et parietes circumspectabantur.

<cautissime> agens Martin: egens M: <t>egens Lipsius: <se t>egens Vertranius: <sui t>egens Müller: reticens Weissenborn

The conceit is not simply that 'the walls have ears' but that they can speak and thus repeat what they have heard: for this complex of ideas see Fraenkel on Aesch. Ag. 37, Dyck on Cic. Cael. 60; Otto 266, Tosi 106 §230; Santoro L'Hoir 166 7.133 muta atque inanima (again at H. 1.84.4) is a fairly common combination (Cic. Verr. 5.171, ND 1.36, Rhet. Herenn. 4.66, Quint. 5.11.23, 5.13.23); tectum and parietes are commonly combined from Cicero onwards (e.g. Verr. 5.184).

133 In The Times for 20 January 1992 an article on informers in the former East Germany by the brilliant Bernard Levin was accompanied by a Peter Brookes cartoon depicting two apprehensive women walking alongside a wall which is topped with barbed wire and has grown a pair of very large ears. The conceit, albeit differently applied, also featured in numerous posters in World War II.

Tuesday, September 27, 2022

Whence We Come, and Whither We Go

An Anthology of Sanskrit Court Poetry: Vidyākara's "Subhāṣitaratnakoṣa" translated by Daniel H.H. Ingalls (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1965 = Harvard Oriental Series, 44), p. 427 (number 1634):

The body is but the product of semen and of blood,Greek Anthology 10.45 (by Palladas; tr. W.R. Paton:

which then becomes a meal for death, a dwelling place for suffering,

a tavern for disease. A man may know all this

and yet, perforce, from lack of judgment,

drowning in the sea of ignorance,

he yearns for love, for sons, for women and for land.

[ŚILHAṆA COLLECTION]

If thou rememberest, O man, how thy father sowed thee, thou shalt cease from thy proud thoughts. But dreaming Plato hath engendered pride in thee, calling thee immortal and a "heavenly plant." "Of dust thou art made. Why dost thou think proudly?" So one might speak, clothing the fact in more grandiloquent fiction; but if thou seekest the truth, thou art sprung from incontinent lust and a filthy drop.Marcus Aurelius, Meditations 4.48.2 (tr. Gregory Hays):

Ἄν μνήμην, ἄνθρωπε, λάβῃς ὁ πατήρ σε τί ποιῶν

ἔσπειρεν, παύσῃ τῆς μεγαοφροσύνης.

ἀλλ᾽ ὁ Πλάτων σοὶ τῦφον ὀνειρώσσων ἐνέφυσεν,

ἀθάνατόν σε λέγων καὶ φυτὸν οὐράνιον.

ἐκ πηλοῦ γέγονας· τί φρονεῖς μέγα; τοῦτο μὲν οὕτως

εἶπ’ ἄν τις, κοσμῶν πλάσματι σεμνοτέρῳ.

εἰ δὲ λόγον ζητεῖς τὸν ἀληθινόν, ἐξ ἀκολάστου

λαγνείας γέγονας καὶ μιαρᾶς ῥανίδος.

Yesterday a blob of semen; tomorrow, embalming fluid, ash.Pirke Aboth 3 (tr. Michael L. Rodkinson):

ἐχθὲς μὲν μυξάριον, αὔριον δὲ τάριχος ἢ τέφρα.

Aqabia b. Mahalallel used to say: "Consider three things, and thou wilt not fall into transgression: know whence thou comest, whither thou art going, and before whom thou art about to give account and reckoning; know whence thou comest — from a fetid drop, and whither thou art going — to worm and maggot; and before whom thou art about to give account and reckoning: before the King of the kings of kings, the Holy One, blessed be He."

Zelus Domus Tuae Comedit Me

Euripides, Ion 102-111 (tr. Ronald Frederick Willetts):

As for myself, mine is the task

I have always done since my childhood.

With these branches of bay and these sacred

garlands I will brighten Apollo's

portals, cleanse the floor with

sprinklings of water,

put to flight with my arrows the birds

that foul the offerings.

Since I have neither mother nor father,

I revere the temple of Phoebus

that has nursed me.

ἡμεῖς δέ, πόνους οὓς ἐκ παιδὸς

μοχθοῦμεν ἀεί, πτόρθοισι δάφνης

στέφεσίν θ᾽ ἱεροῖς ἐσόδους Φοίβου

καθαρὰς θήσομεν ὑγραῖς τε πέδον 105

ῥανίσιν νοτερόν· πτηνῶν τ᾽ ἀγέλας,

αἳ βλάπτουσιν σέμν᾽ ἀναθήματα,

τόξοισιν ἐμοῖς φυγάδας θήσομεν·

ὡς γὰρ ἀμήτωρ ἀπάτωρ τε γεγὼς

τοὺς θρέψαντας 110

Φοίβου ναοὺς θεραπεύω.

Epitaph of a Boxer

Reinhold Merkelbach and Josef Stauber, edd., Steinepigramme aus dem griechischen Osten, Bd. 4: Die Südküste Kleinasiens, Syrien und Palaestina (München: K.G. Säur, 2002), p. 239, number 20/01/02, from Seleukeia in Pieria, 2nd/3rd century AD (text simplified by me):

[⏑–⏑] Ἑλλήσποντος Εἴλιον νέον·My rough translation:

ἄλλαις δ' Ἐπειοὶ πυγμάχον κατέστεφον.

νέος πατρῴοις κείμενος τύμβοις λέγω

Ἤλεις Σελεύκου· χαίρετε εὐφραίνεσθέ τε·

κενῶν γὰρ ἡμεῖν τέρμα μόχθων Ἀίδης.

[...] Hellespont and New Ilium; with other (wreathes?) the Epeans crowned me, a boxer. A young man lying in the ancestral grave, I, Eleis son of Seleukos, say: Rejoice and make merry; for the goal of our empty toils is Hades.The Epeans were a tribe in Elis, and Olympia was located in Elis. As Merkelbach and Stauber note, this probably refers to an Olympic victory. The inscription is also in Werner Peek, Griechische Vers-Inschriften, Vol. I: Grab-Epigramme (Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 1955), p. 610, # 1957.

Monday, September 26, 2022

The Worship of Artemis

Edith Hall, Introducing the Ancient Greeks: From Bronze Age Seafarers to

Navigators of the Western Mind (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2014), p. 257:

The New Testament says little on the topic of the hedonistic old religion that Dionysius and Damaris now abandoned. It mentions only Zeus, Hermes, and Artemis at all, and it was Artemis who was seen, especially in the eastern Aegean and Turkey, as the most potent symbol of paganism. Pagan authors such as Artemidorus of Daldis in Lydia (Asia Minor) attest to the continuing authority of the cult of Artemis in Ephesus in the second century AD during the age of the Antonines: One of the hundreds of dreams he records in his five-book Interpretation of Dreams (the ancient book that inspired Sigmund Freud) was dreamed by a prostitute in Ephesus who wanted entry to the temple. Inscriptions confirm the regional importance of the goddess: One, found on the island of Patmos, shows how seriously Artemis was still being taken by her priestess, Vera, in the third century AD: "Artemis herself, the virgin huntress, herself chose Vera as her priestess, the noble daughter of Glaukias, so that as water-carrier at the altar of the Patmian goddess she should offer sacrifices of the fetuses of quivering goats which had already been sacrificed." Patmos, described as "the most sacred island" of Artemis (Artemis of the Ephesians) in Acts 19:28, was under Ephesian governance. But it was also the site of some of the principal early Christian activities and traditions. In Glaukias's proud description of his daughter's selection as priestess to carry the lustral water, and her bloodthirsty sacrifice of pregnant goats and their fetuses, we can hear the defiance of the old pagan religion against the perceived encroachments of the new Christian faith.Translation of the entire inscription by Edith Hall, Adventures with Iphigenia in Tauris: A Cultural History of Euripides' Black Sea Tragedy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), pp. 142-143:

Artemis herself, the virgin huntress, herself chose Vera as her priestess, the noble daughter of Glaukias, so that as water-carrier at the altar of the Patmian goddess she should offer sacrifices of the foetuses of quivering goats which had already been sacrificed. As a young girl Vera was raised in Artis [i.e. Lebedos, north of Ephesus], but she was born and nursed on Patmos, the island of which Leto's daughter is most proud, which she protects as her throne in the deeps of the Aegean Sea, from the time when the warrior Orestes, having brought her from Scythia, installed her, and he was cured of the terrible madness which followed the murder of his mother. Now the lovely Vera, daughter of the wise doctor Glaukias, has sailed by the will of Scythian Artemis over the wintry swell of the waters of the Aegean in order to bring lustre to the rites and the festival, as the divine law instructed.Greek text from Reinhold Merkelbach and Josef Stauber, Steinepigramme aus dem griechischen Osten, Bd. I: Die Westküste Kleinasiens von Knidos bis Ilion (Stuttgart; B.G. Teubner, 1998), p. 169:

αὐτὴ παρθενικὴ Ἐλαφήβολος ἀρήτειραν

θήκατο κυδαλίμην Γλαυκίεω θύγατρα

ὑδροφόρον Βήραν Πατνίηι παραβώμια ῥέξαι

σπαιρόντων αἰγῶν ἔμβρυα καλλιθύτων.

εἰν Ἄρτει δ' ἐτράφη νεαρὴ παῖς, ἡ δὲ τιθήνη

ἐκ γενετῆς Βήρας κὲ τροφός ἐστι Πάτνος,

νῆσσος ἀγαυοτάτη Λητωΐδος, ἧς προβέβηκε

βένθεσιν Αἰγαίοις ἕδρανα, ῥυομένην

ἐξότε μιν Σκυθίηθεν Ἀρήϊος εἷσεν Ὀρέστης

παυσάμενος στυγερῆς μητροφόνου μανίης·

νῦν δ' ἐρατὴ Βήρα, θυγάτηρ σοφοῦ ἰητῆρος

Γλαυκίεω βουλαῖς Ἀρτέμιδος Σκυθίης

Αἰγαίου πλώσασα ῥόου δυσχείμερον οἶδμα

ὄργια κὲ θαλίην, ὡ̣ς θέμις, ἠγλάϊσεν.

Muck, or the Greatest Play Ever Written?

Excerpts from Terence Rattigan, The Browning Version:

TAPLOW. Well, anyway, sir, it's a good deal more exciting than this muck. (Indicating his book.)Aeschylus, Agamemnon 1399-1400 (tr. Eduard Fraenkel):

FRANK. What is this muck?

TAPLOW. Aeschylus, sir. The Agamemnon.

FRANK. And your considered view is that the Agamemnon of Aeschylus is muck, is it?

TAPLOW. Well, no, sir. I don't think the play is muck — exactly. I suppose, in a way, it's rather a good plot, really, a wife murdering her husband and having a lover and all that. I only meant the way it's taught to us — just a lot of Greek words strung together and fifty lines if you get them wrong.

[....]

He picks up a text of the Agamemnon and TAPLOW does the same.

Line thirteen hundred and ninety-nine. Begin.

TAPLOW. Chorus. We — are surprised at —

ANDREW. (Automatically.) We marvel at.

TAPLOW. We marvel at — thy tongue — how bold thou art — that you —

ANDREW. Thou. (ANDREW'S interruptions are automatic. His thoughts are evidently far distant.)

TAPLOW. Thou — can —

ANDREW. Canst —

TAPLOW. Canst — boastfully speak —

ANDREW. Utter such a boastful speech —

TAPLOW. Utter such a boastful speech — over — (In a sudden rush of inspiration.) — the bloody corpse of the husband you have slain —

ANDREW looks down at his text for the first time. TAPLOW looks apprehensive.

ANDREW. Taplow — I presume you are using a different text from mine —

TAPLOW. No, sir.

ANDREW. That is strange for the line as I have it reads: ἥτις τοιόνδ' ἐπ' ἀνδρὶ κομπάζεις λόγον. However diligently I search I can discover no 'bloody' — no 'corpse' — no 'you have slain'. Simply 'husband' —

TAPLOW. Yes, sir. That’s right.

ANDREW. Then why do you invent words that simply are not there?

TAPLOW. I thought they sounded better, sir. More exciting. After all she did kill her husband, sir. (With relish.) She's just been revealed with his dead body and Cassandra's weltering in gore —

ANDREW. I am delighted at this evidence, Taplow, of your interest in the rather more lurid aspects of dramaturgy, but I feel I must remind you that you are supposed to be construing Greek, not collaborating with Aeschylus.

TAPLOW. (Greatly daring.) Yes, but still, sir, translator's licence, sir — I didn't get anything wrong — and after all it is a play and not just a bit of Greek construe.

ANDREW. (Momentarily at a loss.) I seem to detect a note of end of term in your remarks. I am not denying that the Agamemnon is a play. It is perhaps the greatest play ever written —

TAPLOW. (Quickly.) I wonder how many people in the form think that?

We marvel at thy tongue, at the boldness of its speech, to utter such boasting words over thine own husband.See Thomas G. Palaima, "The Browning Version's and Classical Greek," in Bettina Amden et al., edd., Noctes Atticae: 34 Articles on Graeco-Roman Antiquity and its Nachleben. Studies Presented to Jørgen Mejer on his Sixtieth Birthday March 18, 2002 (Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press, 2002), pp. 199-214.

θαυμάζομέν σου γλῶσσαν, ὡς θρασύστομος,

ἥτις τοιόνδ' ἐπ' ἀνδρὶ κομπάζεις λόγον.

Sunday, September 25, 2022

Incomparable Taste

An Anthology of Sanskrit Court Poetry: Vidyākara's "Subhāṣitaratnakoṣa" translated by Daniel H.H. Ingalls (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1965 = Harvard Oriental Series, 44), pp. 425-426 (number 1628):

A dog will gnaw at a human bone,

and though it be wormy, covered with spittle, stinking,

repulsive and even void of meat,

he delights in its incomparable taste.

If even Indra should come by,

the dog would look upon him with suspicion,

for one who is low does not consider

that what he has may not be worth the having.

[ŚŪLA? ŚILHAṆA COLLECTION, BHARTṚHARI COLLECTION]

Rumor

Chariton, Callirhoe 3.2.7 (tr. G.P. Goold):

Rumor is the swiftest of all things. She flits through the air and no way is closed to her. Because of her, nothing unusual can remain secret.

πάντων γάρ πραγμάτων όξύτατόν έστιν ή Φήμη· δι' άέρος άπεισιν άκωλύτους έχουσα τάς όδούς· δια ταύτην ούδέν δύναται παράδοξον λαθεῖν.

The Text

John Dewar Denniston and Denys Page, edd., Aeschylus, Agamemnon (1957; rpt. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989), p. xxv (from Page's Introduction):

That is what is in the text; and, however crude and inadequate it may appear, in the text it remains, it cannot be removed....This plain testimony of the text is so displeasing that attempts have been made, all in vain, to substitute explanations other than, and inconsistent with, that which the poet offers.

Saturday, September 24, 2022

Don't Kick Against the Pricks

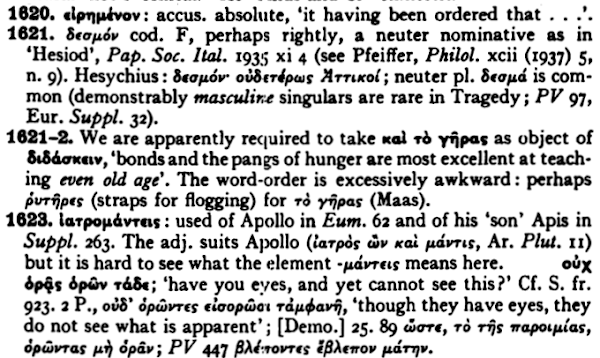

Aeschylus, Agamemnon 1619-1624 (Aegisthus to the chorus of old men; tr. Herbert Weir Smyth):

Old as you are, you shall learn how bitter it is at your age to be schooled when prudence is the lesson set before you. Bonds and the pangs of hunger are far the best doctors of the spirit when it comes to instructing the old. Do you have eyes and lack understanding? Do not kick against the goads lest you strike to your own hurt.John Dewar Denniston and Denys Page ad loc.: Related post: Eyes and Ears.

γνώσῃ γέρων ὢν ὡς διδάσκεσθαι βαρὺ

τῷ τηλικούτῳ, σωφρονεῖν εἰρημένον. 1620

δεσμὸς δὲ καὶ τὸ γῆρας αἵ τε νήστιδες

δύαι διδάσκειν ἐξοχώταται φρενῶν

ἰατρομάντεις. οὐχ ὁρᾷς ὁρῶν τάδε;

πρὸς κέντρα μὴ λάκτιζε, μὴ παίσας μογῇς.

1621 δεσμὸς T: δεσμὸν GF: δεσμοὶ Karsten

τὸ γῆρας τ: ῥυτῆρες Maas

1624 παίσας sch. Pind. P. 2.173 c: πήσας τ

The Simple Life

An Anthology of Sanskrit Court Poetry: Vidyākara's "Subhāṣitaratnakoṣa" translated by Daniel H.H. Ingalls (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1965 = Harvard Oriental Series, 44), p. 425 (number 1624):

The sky for garment, my hollow hand for cup,On "my hollow hand for cup" cf. Diogenes Laertius 6.2.37 (on Diogenes the Cynic; tr. R.D. Hicks):

deer for my companions, meditation for my sleep,

the earth for couch and roots for food:—

When will this, my fondest heart's desire, be fulfilled

to set the crown upon my happiness?

[ŚILHAṆA COLLECTION]

One day, observing a child drinking out of his hands, he cast away the cup from his wallet with the words, "A child has beaten me in plainness of living."

θεασάμενός ποτε παιδίον ταῖς χερσὶ πῖνον ἐξέρριψε τῆς πήρας τὴν κοτύλην, εἰπών, "παιδίον με νενίκηκεν εὐτελείᾳ."

Friday, September 23, 2022

No Subtitles

Jay H. Jasanoff and Brian D. Joseph, "Calvert Ward Watkins," Language 91.1 (March, 2015) 245-252 (at 245):

Cal began as a prodigy and never stopped being one. Exposure to Latin and Greek in school made him hungry for more, and by the time he was fifteen he had decided to be an Indo-Europeanist. He had already shown himself to be a remarkable practical language learner. Once, when he changed schools and was found to be behind the class in French, the problem was solved by his father taking him to see French movies, making sure he always got seated behind a lady in a fancy hat so that he would be unable to see the subtitles. In later years it was rumored, no doubt apocryphally, that he could get into a train at one end of a European country whose language he did not know and come out at the other end a fluent speaker. As he always emphasized, however, being a 'linguist' in this sense had nothing to do with being a linguist in the other. He would illustrate the point by relating how, when the famous Indo-Europeanists Carl Darling Buck (American) and Antoine Meillet (French) met face to face, they had no common language and had to use an interpreter.Id. (at 248-249):

The best way to recover older syntactic patterns, he held, was to build on synchronically anomalous structures of the type God save the king in English, which had to be old because they could not be new. To underscore the point, he quoted one of his favorite aphorisms: 'The first law of comparative grammar is that you've got to know what to compare'. A few pages later, expatiating on the near-identity of the Hittite, Vedic, and Greek versions of a single quasi-attested sentence ('The one who wins gets a prize'), he had occasion to drop another mot of which he was fond: 'If we want to know how the Indo-Europeans talked, it can be useful to consider what they talked about.'Id. (at 250-251):

Cal was a charismatic personality and an inspirational teacher. He had no use for the kind of teaching he disapprovingly referred to as 'indogermanisch *a ergibt a' ('IE *a gives a')—recycling cut and dried factual knowledge in the classroom. Books could do that after hours. Classes for Cal were an occasion for object lessons in how knowledge could be used to generate more knowledge. He was never happier than when he could stand before a roomful of students and demonstrate, with immense flair, how a word, phrase, or motif in one IE language was historically the same, after secondary developments were stripped away, as a word, phrase, or motif in another. There was no unseemly haste in his courses; he took seriously Jakobson's definition of philology as 'the art of reading slowly', and fully savored every construction, formula, and metrical unit before moving on to the next. He taught by example. His lectures were carefully crafted masterpieces, sometimes ending with a return to the theme with which he had begun, in the manner of an IE-style ring composition. A student who followed his model not only learned how to construct an argument—a skill surprisingly rare in philology-heavy fields—but also acquired an almost esthetic sense of what kinds of problems were worth working on and what kinds of solutions were worth looking for. While always insisting on the highest standards of scholarly knowledge and accuracy, he believed that bold and elegant ideas deserved to be sought out and nurtured, even if they sometimes failed to bear fruit. Not the least of the lessons he taught was the need to be wrong some of the time. 'Was ich da geschrieben habe, ist Quatsch' ('What I wrote there is nonsense') he liked to say, quoting a favorite remark of the great Celticist Rudolf Thurneysen (who, like Cal, was usually right).

Gaussargues

Lawrence Durrell, Spirit of Place: Letters and Essays on Travel, ed. Alan G. Thomas (New York: Open Road, 2012), page number unknown:

[T]he little Roman town with its graceful bridge and ambling trout-stream was certainly somewhere to linger. It figures in no guidebook—its time-saturated antiquities are considered unimportant beside those of its neighbours. But it is a jewel with its tiny medieval town and clock-tower; its rabbit warren streets and carved doorways with their battered scutcheons and mason's graffiti. Rooks calling too, from the old fort, their cries mingled with the hoarse chatter rising from the cafes under the planes. Gaussargues!

And here Pepe somehow came into his own—on the shady waterfront café before the tavern-hotel called "The Knights" where I was lodged, and where the affairs of the world were debated to the music of river-water and the hushing of the plane-fronds above us. Yes, if it was not entirely a new Pepe it was an extension of the old flamboyant figure in new terms—for here he was at home, among his friends, these dark-eyed, keen-visaged gentry wearing black berets and coloured shirts and belts. Their conversation, the whole humour and bias of their lives revolved about bulls and the cockades they carried, about football matches against the hated northern departments and the celestial fouls perpetrated during them; and more concretely about fishing and vines and olive-trees. Here too one entered the mainstream of meridional hospitality where a drink refused was an insult given—and where travellers find their livers insensibly turning into pigskin suitcases within them. Such laughter, such sunburned faces, and such copious potations are not, I think, to be found anywhere else outside the pages of Gargantua. At times the rose-bronze moon came up with an air of positive alarm to shine down upon tables covered with a harvest of empty glasses and bottles, or to gleam upon the weaker members of the company extended like skittles in the green grass of the river-bank, their dreams presumably armouring them against the onslaughts of the mosquitoes. Those of us who by this time were not too confused with wine and bewitched by folklore to stand upright and utter a prayer to Diana, managed to help each other tenderly, luxuriously to bed.…

Murier the dentist, Thoma the notary, Carpe the mason, Rickard the postmaster, Blum the mayor, and Gradon the chief policeman: such an assembly of moustaches and expressions as would delight a Happy Families addict. Massively, like old-fashioned mahogany furniture, they sat away their lives under the planes—village characters belonging to the same over- elaborated myth which created Panurge. They were terrific and they knew it!

Literal Translation

Aaron Hill, A Full and Just Account of the Present State of the Ottoman Empire (London: John Mayo, 1709), p. xiv:

A Literal Translation commonly appears Confin'd, Uneasy, Close and Aukward, like a Streight-Lac'd Lady in her New Made Stays, but when the Version has put on an Easy Paraphrase, and the Fine Lady is compleatly Dress'd, with Ribbons, Manteau, and her Looser Ornaments, tho' they are still the same, they were before, they brightly double Former Graces, and become Adorn'd with an Attractive Majesty.I owe the reference to Edith Hall, "Classics Invented: Books, Schools, Universities and Society 1679–1742," in Stephen Harrison and Christopher Pelling, edd., Classical Scholarship and Its History From the Renaissance to the Present: Essays in Honour of Christopher Stray (Berlin: de Gruyter, 2021), pp. 35-58 (at 45).

The Blood of the Lamb

Painted wooden panel depicting a sacrificial procession, 6th century B.C. (Athens, National Archaeological Museum, inv. no. 16464):

Matthew Dillon, Girls and Women in Classical Greek Religion (London: Routledge, 2002), p. 228, with notes on p. 355:

Four painted wooden pinakes (offering tablets; they are all polychromatic) dating to 540–520 BC were discovered in a cave, where the nymphs were worshipped, at Pitsa near Sikyon in the Peloponnese. The best-preserved pinax, with the colouring and the entire tablet almost intact, depicts a sacrificial scene in which women are prominent (Figure 7.3).105 The names of the dedicators, the deities being honoured and the name of the painter are provided by the painted inscriptions on the pinax. On the far right is an altar of the nymphs, associated with childbirth, and a procession is shown which has just arrived in front of the altar. First in front of the altar is a woman; she holds an oinochoe in her right hand, from which she appears to be about to pour a libation. On her head she carries a large flat basket, on which are two vessels on either side of what appears to be a box. The box presumably contains sacrificial items, such as perhaps the knife. She is immediately followed by a boy who leads a sheep by a rope; like the other figures the boy is wreathed. He is followed by two males, also boys but larger, yet not adults. One strums a lyre while the other plays the flute. Two women follow carrying sprigs of vegetation, and behind the second woman is a shrouded figure, also clearly carrying a sprig of vegetation; she is taller than the other women, both in height and in girth: she appears to be pregnant (unfortunately the pinax is damaged and her face is lost); the last in the processional line and clearly the largest of the figures, she is the most important and the sacrifice of the sheep is for her benefit. At least two women are named on this pinax: Euthydika and Eupolis, and perhaps a third; these could refer to the three women depicted in the procession.106Jennifer Larson, Greek Nymphs: Myth, Cult, Lore (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), pp. 232-233, with notes on p. 326:

105 Figure 7.3: Pitsa painted wooden plaque, NM 16464; polychrome (mainly blue and red paint for the figures on a cream-brown background); the less well preserved ones are: 16465, 16466, 16467; see SEG 23.264 a–c (Hausmann 1960: 14 pl. 4; Schelp 1975: 86 K16; Robertson 1975: pl. 34d; 1981: pl. 45; Lorber 1979: 93, no. 154, pls 45.154, 46.154; Amyx 1988: 394–5, 543, 604–5; Boardman 1993: pl. vii.64; 1996: 122 fig. 112; van Straten 1995: 57–8, pl. 56; Carratelli 1996: 101; Schefold 1998: pl. 38).

106 A third group of letters could be interpreted as the name 'Ethelonche'.

The discovery in 1934 of Saftulis cave near Sikyon created a sensation when it was found to contain unique examples of archaic painting on wood panels.13 The four votive tablets, or pinakes, had been preserved in the dry atmosphere of the cave, though two were fragmentary. The best-preserved one (figure 5.1) shows a sacrificial scene, with three adult women, younger flute and lyre players, and a slave with the necessary sacrificial wares approaching an altar. A sheep is the intended victim, and the tablet is inscribed with the names of two women, Euthydika and Eucholis, and the words "dedicated to the nymphs." .... One important question is whether similar tablets would have been placed in other nymph caves, or if they were characteristic only of the Sikyon-Corinth area, which was noted for its skilled painters in this period. Indications are that wooden votives were an important part of the rustic cult tradition, and it is most likely that wooden artifacts, including pinakes, have been ost in large numbers from cave sites.14 These tablets (the two best-preserved examples were dated 540–30) provide us with some interesting information about the cult of the nymphs in the sixth century in the eastern Peloponnese. First, the nymphs receive a typical blood sacrifice like that offered to the Olympian gods. There was nothing unusual about such a sacrifice except its value. Other evidence shows that while blood sacrifices for the nymphs were not unknown, lesser offerings were more common. These votive tablets probably commemorated some special occasion that called for a richer-than-usual offering to the nymphs. The prominence of the female dedicators in the sacrificial scene is also suggestive. They invite comparison with the mother of Sostratos in Menander's Dyscolus, who is described as particularly enthusiastic in her devotions to local deities and who makes pilgrimages to their shrines with an entourage of musicians and servants similar to that shown in the tablet.See also A.D. Rizakis, Achaïe III. Les cités achéennes: Épigraphie et histoire (Paris: de Boccard, 2008 = Meletemata, 55), pp. 249-251 (number 185a), and Theodora Kopestonsky, "The Greek Cult of The Nymphs at Corinth," Hesperia 85.4 (October-December 2016) 711-777 (at 760-763).

13. Orlandos (1965) 204–5 s.v. Pitsa; AA 50 (1935) 198; Hausmann (1960) 15–16 fig. 4; Neumann (1979) 27, pl. 12a; Amyx (1988) 2.604–5. The third and fourth tablets show groups of female figures. Tablet inscriptions: BCH 91 (1967) 644–46; SEG 23 (1968) 264.

14. For the popularity of wooden tablets, see Van Straten in Versnel (1981a) 78–79; Ar. Thesm. 770–75; Aen. Tact. 31, 15; Van Straten (1995) 57–58.

Thursday, September 22, 2022

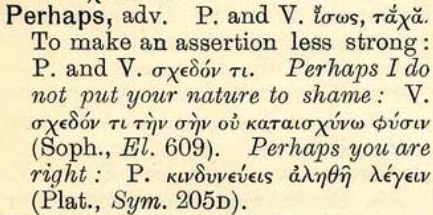

Perhaps

Kenneth Dover, The Greeks, 3rd ed. (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1989), p. 124:

Greek historians were never afraid to use their own judgement. They were willing to say 'I don't know', to speculate about the motives of the people they described, and to qualify their opinions on occasion by 'perhaps' and 'probably'. It is the appearance of words like 'perhaps' which marks the beginning of true historical writing.S.C. Woodhouse, English-Greek Dictionary: A Vocabulary of the Attic Language (London: George Routledge & Sons, 1910), p. 606: ἴσως and τάχα seem to occur more often in Thucydides than in Herodotus.

Wednesday, September 21, 2022

Maybe, Maybe Not

Richard Tarrant, Texts, Editors, and Readers: Methods and Problems in Latin

Textual Criticism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), p. 145:

E.R. Dodds: 'Our editions of Greek and Latin authors are good enough to live with'; D.R. Shackleton Bailey: 'Maybe, maybe not; it all depends on one's standard of living'.1Thanks very much to Christopher Brown for the following remarks:

1 Probably apocryphal, based on Shackleton Bailey's remark that 'when E. R. Dodds pronounced that our editions are good enough to live with, he cannot have been thinking of G. Lehnert's Teubner edition (1905) of the longer declamations falsely attributed to Quintilian' (1976a, 73).

[Tarrant] suggests that he concocted the exchange from a comment made by SB in his review of Hankason published in 1976. Great and prolific scholars often repeat themselves, and it is interesting to note that in a paper from 1975 SB writes, "Professor Dodds of Oxford, himself a highly accomplished textual critic, once opined that our (classical) texts are good enough to live with. I suppose that depends in the first place on one's standard of living" ("Editing Ancient Texts," in H.H. Paper [ed.], Language and Texts: the Nature of Linguistic Evidence [Ann Arbor 1975] 21-32 = Selected Classical Papers [Ann Arbor 1997] 324-335, at 329). That's clearly the source of the 'standard of living' language. I believe that the occasion of Dodds' opining was his inaugural lecture at Oxford, "Humanism and Technique in Greek Studies," which ruffled the feathers of a number of colleagues. Dodds tells the story (along with Bowra’s tart reaction to the lecture) in his autobiography, Missing Persons (Oxford 1977) 127.

Unhappily in Decline

Martha C. Nussbaum, "A Stoic's Confessions," Arion 4.3 (Winter, 1997) 149-160 (at 150):

The old practice of composing Greek prose and verse, now unhappily in decline, yields an active command of vocabulary, syntax, meter, and style that escapes pupils who practice a dead language only by translating.

Slow Writing

Gustave Flaubert, letter to Maxime Du Camp (June 26, 1852; tr. Geoffrey Wall):

May I die like a dog rather than try to rush through even one sentence before it is perfectly ripe.

Que je crève comme un chien plutôt que de hâter d'une seconde ma phrase qui n'est pas mûre.

A Crux in Aeschylus' Agamemnon

Aeschylus, Agamemnon 1440-1443 (Clytemnestra speaking about Cassandra; tr. Herbert Weir Smyth, with his Greek text and apparatus, from the old Loeb Classical Library edition, vol. II, pp. 128-129):

E. Scheer, "Beiträge zur Erklärung und Kritik des Aischylos," Rheinisches Museum 67 (1912) 481–514 (at 494-495, n. 2): λισποτριβής.

A.Y. Campbell, The Agamemnon of Aeschylus, a Revised Text with Brief Critical Notes (Liverpool: University Press, 1936): ναυτικῶν ἑδωλίων / ἵστωρ τρυφῆς, with the following explanation (p. 116): H.D. Broadhead, "Some Passages of the Agamemnon," Classical Quarterly 9.2 (November, 1959) 310-316 (at 315): ὁμοτρίβης. Note that Gottfried Hermann had already written: "poeta si illud in mente habuisset, non ἰσοτρίβης, sed ὁμοτρίβης dixisset."

James Diggle, "Notes on the Agamemnon and Persae of Aeschylus," Classical Review 18.1 (March, 1968) 1-4 (at 2-3): κοιτοτρίβης.

The bibliography is extensive, but see especially Martin L. West, Studies in Aeschylus (Stuttgart: B.G. Teubner, 1990), pp. 220-221.

and here she lies, his captive, and auguress, and concubine, his oracular faithful bedfellow, yet equally familiar with the seamen's benches.The same passage (tr. Alan H. Sommerstein, with his note and Greek text and apparatus, from the new Loeb Classical Library edition of the Oresteia, pp. 174-176):

ἥ τ' αἰχμάλωτος ἥδε καὶ τερασκόπος

καὶ κοινόλεκτρος τοῦδε, θεσφατηλόγος

πιστὴ ξύνευνος, ναυτίλων δὲ σελμάτων

ἰσοτριβής.3

3 ἰσοτριβὴς Rom., ἰστοτριβὴς FV3N: Pauw

and with him this captive, this soothsayer, this chanter of oracles who shared his bed, this faithful consort, this cheap whore306 of the ship's benches.Alan H. Sommerstein, "Comic Elements in Tragic Language: The Case of Aeschylus' Oresteia," in Andreas Willi, ed., The Language of Greek Comedy (2002; rpt. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), pp. 151-167 (at 155–156, footnotes omitted):

306 lit. "mast-rubber", where ἱστός "mast" is metaphorical as in Strabo's tale (8.6.20) of the Corinthian hetaera who said, when taunted with the fact that she did no proper work, "I've lowered three ἱστοί before now in [snapping her fingers?] this length of time". On the obscenity, unparalleled in tragedy, see my discussion in A. Willi ed. The Language of Greek Comedy (Oxford, 2002) 155–6.

ἥ τ' αἰχμάλωτος ἥδε καὶ τερασκόπος,

ἡ κοινόλεκτρος τοῦδε θεσφατηλόγος,

πιστὴ ξύνευνος, ναυτίλων δὲ σελμάτων

ἱστοτρίβης.3

1441 ἡ Karsten: καὶ f.

[Klytaimestra] denounces at great length the extramarital sexual activities of her husband, which in most male Greeks' view—with the sole exception of his insult to her in bringing Kassandra to her home—were none of her business. And in the course of doing so she uses two highly untragic vocabulary items. One is the notorious ἱστοτριβής (1443), referring to Kassandra. It will be necessary to take some time over this word, in view of some of the truly desperate attempts that have been made to keep Aeschylus at this point within the commonly assumed canons of tragic diction. M.L. West (1990a: ad loc.), with a reference to Iliad 1.31, notes coniugis nauticae nocturno muneri diurnum additur: but for one thing one could not do loom-weaving on board an ancient ship, for another, of the two words which on this view would refer to Kassandra's sexual duties, κοινόλεκτρος (1441) and ξύνευνος (1442), neither has anything in its own immediate context to suggest that she is being portrayed as a nautical consort, and for a third, and most importantly, it is absurd to make Klytaimestra climax this passage, which is dripping throughout with her jealousy of the women who replaced her abroad and the one who nearly supplanted her at home, by referring to the ordinary work of a maidservant which, far from being any threat to the mistress of the house, actually emphasizes her superiority inasmuch as she does not have to do it herself! Lloyd-Jones (1978: 58–9), building on a suggestion by Latte, sees an allusion to the practice in at least one Greek state (we do not know which) of punishing women for some offence (probably, but not certainly, unchastity) by making them sit on top of a ἱστός (more likely a loom, as Lloyd-Jones thinks, than a pole, as suggested by O'Daly 1985: 13: the object, according to Hesychius α 2576 [sic, read 2578], was to humiliate, not to torment). This neatly enables us to have our cake and eat it, by allowing ἱστοτριβής to mean 'whore' or the like while keeping Aeschylus free from 'an obscenity … unparalleled in tragic diction' (O'Daly 1985: 13); but it depends on our accepting that a word referring to a very specific punishment, and not one used at Athens, would be instantly intelligible to Aeschylus' Athenian audience. [....] Are we really meant to suppose that he accidentally made Klytaimestra refer to Kassandra, in a sexually charged context, by a word which could so easily be taken to mean πόρνην ἥτις τὸ πέος τρίψοι (Ar. Vesp. 739; cf. also Ar. Ach. 1149, Vesp. 1344)—and that neither he nor anyone else noticed it in rehearsal and changed the word? Unless we emend, we have no alternative but to accept the obscenity. It may be alien to tragedy, but it is far from alien to this particular tragic character. The whole point about Klytaimestra, especially in this scene, is that she breaks all the rules; and this word, prominently placed at the beginning of a line before a pause, is the culmination of her rule-breaking. What is more, by using it she contrives to perpetrate a maximal insult to Kassandra and Agamemnon at once. If, as the comic parallels suggest, ἱστοτριβής would be taken as meaning approximately 'one who gives hand jobs', then on the one hand the princess and prophetess Kassandra (to whom Klytaimestra was so elaborately sympathetic in 1035-46) is being downgraded to the level of the meanest slave in a Peiraeus brothel, and on the other hand it is being insinuated that Agamemnon had been suffering from erectile dysfunction and had needed manual assistance to overcome it.Cf. previously D.C.C. Young, "Gentler Medicines in the Agamemnon," Classical Quarterly 14.1 (May, 1964) 1-23 (at 15, on 1055-1056):

Klytaimestra is saying: 'I have no leisure to rub (wear away) this doorway', i.e. 'I can't wait hanging around the door here'. It is a vulgar expression, and she uses an even more vulgar expression involving the root τριβ- at 1443, where she refers to the corpse of Kassandra as ναυτίλων δὲ σελμάτων ἱστοτρίβης. Casaubon kept the word, translating it 'publicum navis prostibulum'. A ἱστός is anything set upright, an erection. Cf. the slang use of English 'beam', Latin trabs. Strabo, 8.378 [i.e. 8.6.20], has an anecdote about a ἑταίρα who, πρὸς τὴν ὀνειδίζουσαν, ὅτι οὐ φιλεργὸς εἴη οὐδ' ἐρίων ἅπτοιτο, retorted 'ἐγὼ μέντοι ἡ τοιαύτη τρεῖς ἤδη καθεῖλον ἱστοὺς ἐν βραχεῖ χρόνῳ τούτῳ.' ('I took down three beams in three shakes of a cow's tail'). Cf. also παιδοτριβέω sensu obscaeno = παιδεραστέω, Anth. Pal. 12.34.6; 222.2.For some older conjectures see Frederick H.M. Blaydes, ed., Aeschyli Agamemnon (Halle: In Orphanotrophei Libraria, 1898), p. 129: Here is a list of some more recent conjectures.

E. Scheer, "Beiträge zur Erklärung und Kritik des Aischylos," Rheinisches Museum 67 (1912) 481–514 (at 494-495, n. 2): λισποτριβής.

A.Y. Campbell, The Agamemnon of Aeschylus, a Revised Text with Brief Critical Notes (Liverpool: University Press, 1936): ναυτικῶν ἑδωλίων / ἵστωρ τρυφῆς, with the following explanation (p. 116): H.D. Broadhead, "Some Passages of the Agamemnon," Classical Quarterly 9.2 (November, 1959) 310-316 (at 315): ὁμοτρίβης. Note that Gottfried Hermann had already written: "poeta si illud in mente habuisset, non ἰσοτρίβης, sed ὁμοτρίβης dixisset."

James Diggle, "Notes on the Agamemnon and Persae of Aeschylus," Classical Review 18.1 (March, 1968) 1-4 (at 2-3): κοιτοτρίβης.

The bibliography is extensive, but see especially Martin L. West, Studies in Aeschylus (Stuttgart: B.G. Teubner, 1990), pp. 220-221.

Tuesday, September 20, 2022

Engagé Poems

W.H. Auden, A Certain World: A Commonplace Book (New York: The Viking Press, 1970), p. 87:

Hat tip: Karl Maurer, An Introduction to Robert Frost: A Talk with Notes. Edited by Adam Cooper and Taylor Posey (Asheville: Taylor Posey, Publisher, 2021), p. 5, where this passage is quoted. Thanks very much to one of Karl's former students, who sent me this beautiful book as a gift, and thanks to all who are keeping Karl's memory alive.

By all means let a poet, if he wants to, write engagé poems, protesting against this or that political evil or social injustice. But let him remember this. The only person who will benefit from them is himself; they will enhance his literary reputation among those who feel as he does. The evil or injustice, however, will remain exactly what it would have been if he had kept his mouth shut.Auden indicates no source, so presumably the paragraph is his own.

Hat tip: Karl Maurer, An Introduction to Robert Frost: A Talk with Notes. Edited by Adam Cooper and Taylor Posey (Asheville: Taylor Posey, Publisher, 2021), p. 5, where this passage is quoted. Thanks very much to one of Karl's former students, who sent me this beautiful book as a gift, and thanks to all who are keeping Karl's memory alive.

A Constituent Part of Life

Thomas Mann, The Magic Mountain, chapter 5 (Settembrini speaking; tr. James E. Woods):

Permit me, permit me, my good engineer, to tell you something, to lay it upon your heart. The only healthy and noble and indeed, let me expressly point out, the only religious way in which to regard death is to perceive and feel it as a constituent part of life, as life's holy prerequisite, and not to separate it intellectually, to set it up in opposition to life, or, worse, to play it off against life in some disgusting fashion—for that is indeed the antithesis of a healthy, noble, reasonable, and religious view. The ancients decorated their sarcophagi with symbols of life and procreation, some of them even obscene. For the ancients, in fact, the sacred and the obscene were very often one and the same. Those people knew how to honor death. Death is to be honored as the cradle of life, the womb of renewal. Once separated from life, it becomes grotesque, a wraith—or even worse. For as an independent spiritual power, death is a very depraved force, whose wicked attractions are very strong and without doubt can cause the most abominable confusion of the human mind.From Kevin Muse:

Gestatten Sie. Gestatten Sie mir, Ingenieur, Ihnen zu sagen und Ihnen ans Herz zu legen, daß die einzig gesunde und edle, übrigens auch — ich will das ausdrücklich hinzufügen — auch die einzig religiöse Art, den Tod zu betrachten, die ist, ihn als Bestand teil und Zubehör, als heilige Bedingung des Lebens zu begreifen und zu empfinden, nicht aber — was das Gegenteil von gesund, edel, vernünftig und religiös wäre — ihn geistig irgendwie davon zu scheiden, ihn in Gegensatz dazu zu bringen und ihn etwa gar widerwärtigerweise dagegen auszuspielen. Die Alten schmückten ihre Sarkophage mit Sinnbildern des Lebens und der Zeugung, sogar mit obszönen Symbolen, — das Heilige war der antiken Religiosität ja sehr häufig eins mit dem Obszönen. Diese Menschen wußten den Tod zu ehren. Der Tod ist ehrwürdig als Wiege des Lebens, als Mutterschoß der Erneuerung. Vom Leben getrennt gesehen, wird er zum Gespenst, zur Fratze — und zu etwas noch Schlimmerem. Denn der Tod als selbständige geistige Macht ist eine höchst liederliche Macht, deren lasterhafte Anziehungskraft zweifellos sehr stark ist, aber mit der zu sympathisieren ebenso unzweifelhaft die greulichste Verirrung des Menschengeistes bedeutet.

I'm surprised that Woods omits to translate the phrase aber mit der zu sympathisieren... in your selection today from Settembrini's discourse on death.

Here's Lowe-Porter's version, which I think might be better here:For death, as an independent power, is a lustful power, whose vicious attraction is strong indeed; to feel drawn to it, to feel sympathy with it, is without any doubt at all the most ghastly aberration to which the spirit of man is prone.

Fertilizer

Plutarch, Life of Marius 21.3 (tr. Bernadotte Perrin):

Nevertheless, it is said that the people of Massalia fenced their vineyards round with the bones of the fallen, and that the soil, after the bodies had wasted away in it and the rains had fallen all winter upon it, grew so rich and became so full to its depths of the putrefied matter that sank into it, that it produced an exceeding great harvest in after years, and confirmed the saying of Archilochus [fragment 292 West] that "fields are fattened" by such a process.Bijan Omrani, Caesar's Footprints. A Cultural Excursion to Ancient France: Journeys Through Roman Gaul (New York: Pegasus Books, 2017), p. 42:

Μασσαλιήτας μέντοι λέγουσι τοῖς ὀστέοις περιθριγκῶσαι τοὺς ἀμπελῶνας, τὴν δὲ γῆν, τῶν νεκρῶν καταναλωθέντων ἐν αὐτῇ καὶ διὰ χειμῶνος ὄμβρων ἐπιπεσόντων, οὕτως ἐκλιπανθῆναι καὶ γενέσθαι διὰ βάθους περίπλεω τῆς σηπεδόνος ἐνδύσης ὥστε καρπῶν ὑπερβάλλον εἰς ὥρας πλῆθος ἐξενεγκεῖν καὶ μαρτυρῆσαι τῷ Ἀρχιλόχῳ λέγοντι πιαίνεσθαι πρὸς τοῦ τοιούτου τὰς ἀρούρας.

Even the modern French name of the valley, Pourrières, is said to come from the Latin campi putridi, the 'fields of putrescence'.

Monday, September 19, 2022

Lampons!

Camillo P. Merlino, "Some Old French Words in Current English," in Herbert H. Golden, ed., Studies in Honor of Samuel Montefiore Waxman (Boston: Boston University Press, 1969), pp. 56-65 (at 61):

LAMPOON. Clearly derived from lampons, first-person plural of the Old French lamper, a nasal formation from the Anglo-Saxon lapian, "to lap up, to guzzle," lampoon came to mean a drinking song; it is from the refrain lampons "let's drink," frequently recurring in ribald and satirical songs. From this background emerges our familiar lampoon in all its connotations. In modern French there still remains the popular lampée (f.) grande gorgée de liquide qu'on hume d'un coup, such as une lampée de vin. But lampons, strangely enough, has fallen by the wayside.The first thing that sets off my bullshit detector is the claim that an Old French word is derived from an Anglo-Saxon word. Unlikely. See Calvert Watkins, The American Heritage Dictionary Indo-European Roots (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1985), p. 34:

lab-. Lapping, smacking the lips; to lick. Variant of leb-2. 1. Germanic *lapjan in Old English lapian, to lap up: LAP2. 2. Nasalized form *la-m-b- in: a. Germanic *lamp- in French lamper, to gulp down: LAMPOON; b. Latin lambere, to lick: LAMBENT. [Pok. lab- 651.]Second, I'm not sure what is meant by the assertion that "lampons ... has fallen by the wayside." As a verb it survives as a toast: see e.g. Richard Olney, Lulu's Provençal Table (London: Grub Street, 2013), page number unknown:

The animated discussions at table turn around the food, the wines, and their relations to one another. As euphoria gains ground, Lucien may ask everyone to stand while he solemnly intones the ritual toast to "notre chère Méduse," figurehead of the Provençal wine confraternity, after which all present drain their glasses ("Lampons!") and exclaim "Alléluia! Alléluia!"On the etymology of lampoon, see Leo Spitzer, "Anglo-French Etymologies," Studies in Philology 41.4 (October, 1944) 521-543 (at 525-527).

Deserters

Homer, Iliad 5.532 = 15.564 (tr. A.T. Murray, rev. William F. Wyatt):

From those that flee springs neither glory nor any defence.The same (tr. Peter Green):

φευγόντων δ᾽ οὔτ᾽ ἂρ κλέος ὄρνυται οὔτέ τις ἀλκή.

Runaways get no glory, win no battles.

The Affair of the Vultures

Plutarch, Life of Marius 17.3 (tr. Bernadotte Perrin):

The affair of the vultures, however, which Alexander of Myndus relates [fragment 26 Wellmann], is certainly wonderful. Two vultures were always seen hovering about the armies of Marius before their victories, and accompanied them on their journeys, being recognized by bronze rings on their necks; for the soldiers had caught them, put these rings on, and let them go again; and after this, on recognizing the birds, the soldiers greeted them, and they were glad to see them when they set out upon a march, feeling sure in such cases that they would be successful.W. Geoffrey Arnott, Birds in the Ancient World from A to Z (London: Routledge, 2007), p. 92:

τὸ δὲ περὶ τοὺς γῦπας θαύματος ἄξιον Ἀλέξανδρος ὁ Μύνδιος ἱστόρηκε. δύο γὰρ ἐφαίνοντο πρὸ τῶν κατορθωμάτων ἀεὶ περὶ τὰς στρατιὰς καὶ παρηκολούθουν γνωριζόμενοι χαλκοῖς περιδεραίοις· ταὐτὰ δὲ οἱ στρατιῶται συλλαβόντες αὐτούς περιῆψαν, εἶτα ἀφῆκαν· ἐκ δὲ τούτου γνωρίζοντες ἠσπάζοντο αὐτούς οἱ στρατιῶται καὶ φανέντων ἐπὶ ταῖς ἐξόδοις ἔχαιρον ὡς ἀγαθὸν τι πράξοντες.

Their habit of flocking near armies on the march or in battle (Aristotle HA 563a5–12, Alexander of Myndos fr. 26 Wellmann, Aelian NA 2.46) was interpreted as implying that the birds realised battles produced corpses to eat, but is better explained by the fact that pack animals with provisions of meat always accompanied armies.See M. Wellmann, "Alexander von Myndos," Hermes 26.4 (1891) 481-566 (fragment 26 on p. 553).

Tendentious Misreadings of Antiquity

Brent Shaw, "A Groom of One's Own?" The New Republic (July 24, 1994), a review of John Boswell, Same-Sex Unions in Premodern Europe (New York: Villard Books, 1994):

The data of the past may not be all that happy for the liberationist movements of our time. Why else would those movements come into being? But what the sources record is, for better or for worse, what the sources record. A good part of what they record, certainly, is made up of systematic and successful repressions; but tinkering with the moral balance of the past is a disservice to the study of history and to the reform of society. The past is dead. We cannot change it. What we can change is the future; but the way to a better future requires an unsentimental and accurate understanding of what happened in the past, and why. A more civil and humane modernity will not be achieved by tendentious misreadings of antiquity.

Sunday, September 18, 2022

A Rural Retreat

Amphis, fragment 17 (tr. S. Douglas Olson):

Then isn't isolation as good as gold?

The fundamental source of a good life for human beings is a piece of land;

it's the only thing capable of concealing poverty.

Whereas the city is a theatre full of patent bad luck.

εἶτ' οὐχὶ χρυσοῦν ἐστι πρᾶγμ' ἐρημία;

ὁ πατήρ γε τοῦ ζῆν ἐστιν ἀνθρώποις ἀγρός,

πενίαν τε συγκρύπτειν ἐπιστάται μόνος·

ἄστυ δὲ θέατρον ἀτυχίας σαφοῦς γέμον.

2 πατήρ codd.: δοτήρ Elter: σωτήρ Kock

Beatitudes

An Anthology of Sanskrit Court Poetry: Vidyākara's "Subhāṣitaratnakoṣa" translated by Daniel H.H. Ingalls (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1965 = Harvard Oriental Series, 44), p. 425 (number 1621):

Happy are they who pass childhood, youth and ageRelated post: Recipes for Happiness.

gamboling in the dirt, in sensual pleasures and in peace;

playing ever in a lap

of mother, of lotus-eyed enchantress and of holy rivers,

where in each several case they drink their fill

of breast, of lower lip, of stream.

Luther on His Impending Death

Analecta Lutherana et Melanthoniana. Tischreden Luthers und Aussprüche Melanthons, ed. Georg Loesche (Gotha: Friedrich Andreas Perthes, 1892), p. 384 (§ 609, Luther to his wife, my translation, with help from a friend):

Indeed, it is as I've often said; I'm the ripe turd and the world is the gaping arsehole. So we will certainly be separated.

Es ist doch, wie ich offt gesagtt habe; ich bin der reiffe Dreck; so ist die wellt das weitte Arschloch. Darumb sein wir wol zu scheiden.

Labels: noctes scatologicae

Words, But No Deeds

Sophocles, Electra 319 (tr. H.D.F. Kitto):

He promises—and that is all he does.The same (tr. David Grene):

φησίν γε· φάσκων δ᾽ οὐδὲν ὧν λέγει ποεῖ.

He says he is—but does nothing of what he says.

A Loudmouth

Plutarch, Life of Alcibiades 26.6 (tr. Bernadotte Perrin):

He had a helper, too, in Thrasybulus of Steiris, who went along with him and did the shouting; for he had, it is said, the biggest voice of all the Athenians.

συνέπραττε δ᾿ αὐτῷ καὶ Θρασύβουλος ὁ Στειριεὺς ἅμα παρὼν καὶ κεκραγώς· ἦν γάρ, ὡς λέγεται, μεγαλοφωνότατος Ἀθηναίων.

Saturday, September 17, 2022

If You Really Want to Know

Aristophanes, Wasps 85-86 (tr. Jeffrey Henderson):

You're getting nowhere with all this hot air; you'll never find the answer.

If you really want to know, then be quiet.

ἄλλως φλυαρεῖτ᾽· οὐ γὰρ ἐξευρήσετε.

εἰ δὴ 'πιθυμεῖτ᾽ εἰδέναι, σιγᾶτέ νυν.

Who?

An Anthology of Sanskrit Court Poetry: Vidyākara's "Subhāṣitaratnakoṣa" translated by Daniel H.H. Ingalls (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1965 = Harvard Oriental Series, 44), p. 423 (number 1615):

He has crossed all rivers of desire

and contemned all pain.

With grief at parting from his joys assuaged

and impure thoughts removed,

he has reached happiness at last and with closed eyes

attains complete contentment. Who?

Why, a fat old corpse in a graveyard.

Overcoming Fear

Plutarch, Life of Marius 16.2 (tr. Bernadotte Perrin):

For he considered that their novelty falsely imparts to terrifying objects many qualities which they do not possess, but that with familiarity even those things which are really dreadful lose their power to affright.

ἡγεῖτο γὰρ πολλὰ μὲν ἐπιψεύδεσθαι τῶν οὐ προσόντων τὴν καινότητα τοῖς φοβεροῖς, ἐν δὲ τῇ συνηθείᾳ καὶ τὰ τῇ φύσει δεινὰ τὴν ἔκπληξιν ἀποβάλλειν.

Friday, September 16, 2022

An Ancient Lynching

Diodorus Siculus 1.83.6-9 (tr. C.H. Oldfather):

[6] And whoever intentionally kills one of these animals is put to death, unless it be a cat or an ibis that he kills; but if he kills one of these, whether intentionally or unintentionally, he is certainly put to death, for the common people gather in crowds and deal with the perpetrator most cruelly, sometimes doing this without waiting for a trial. [7] And because of their fear of such a punishment any who have caught sight of one of these animals lying dead withdraw to a great distance and shout with lamentations and protestations that they found the animal already dead. [8] So deeply implanted also in the hearts of the common people is their superstitious regard for these animals and so unalterable are the emotions cherished by every man regarding the honour due to them that once, at the time [60 or 59 B.C.] when Ptolemy their king had not as yet been given by the Romans the appellation of "friend" and the people were exercising all zeal in courting the favour of the embassy from Italy which was then visiting Egypt and, in their fear, were intent upon giving no cause for complaint or war, when one of the Romans killed a cat and the multitude rushed in a crowd to his house, neither the officials sent by the king to beg the man off nor the fear of Rome which all the people felt were enough to save the man from punishment, even though his act had been an accident. [9] And this incident we relate, not from hearsay, but we saw it with our own eyes on the occasion of the visit we made to Egypt.Anne Burton ad loc.:

Herodotus, II, 65 says that the unintentional killing of a hawk or an ibis meant death. Wiedemann, Herodots zweites Buch, p. 282, suggests that this varied from nome to nome, depending on which animals were considered sacred locally. But since the hawk and ibis (Horus and Thoth) were held to be sacred throughout most of Egypt, Herodotus is probably substantially correct. Presumably Diodorus includes the cat because he himself saw the incident he describes. This must have happened in a district where the cat was held to be particularly sacred, and it is therefore reasonable to assume that Diodorus visited Bubastis.Alexander Meeus, "Life Portraits: Royals and People in a Globalizing World," in Katelijn Vandorpe, ed., A Companion to Greco-Roman and Late Antique Egypt (Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2019), pp. 89-99 (at 94):

Since this is one of very few such personal experiences that Diodorus has included in his work, it is clear that it must have made a great impression on him. Although it has been observed that Diodorus' attitude toward Egypt was more positive than that of many of his contemporaries (Isaac 2004, p. 359; Muntz 2017, pp. 228–231), the event may have made such an impression because the animal worship appeared so bizarre to him (cf. Smelik and Hemelrijk 1984):As for the various services which these animals require, the Egyptians not only do not try to avoid them or feel ashamed to be seen by the crowds as they perform them, but on the contrary, in the belief that they are engaged in the most serious rites of divine worship, they assume airs of importance, and wearing special insignia make the rounds of the cities and the countryside. (Diodorus Siculus 1.83.4, translation Oldfather, Loeb Classical Library)Was this the embassy of which Cicero would have been a member, had he accepted the invitation to join (Cicero, Epistulae ad Atticum 2.5.1)? At any rate, we would love to know how the Senate reacted to the execution of a Roman ambassador over the killing of a cat, and one wonders whether Cicero was thinking — among other things — of this episode when he asked some 15 years later:Who does not know of the custom of the Egyptians? Their minds are infected with degraded superstitions and they would sooner submit to any torment than injure an ibis or asp or cat or dog or crocodile, and even if they have unwittingly done anything of the kind there is no penalty from which they would recoil. (Cicero, Tusculanae disputationes 5.78, translation King, Loeb Classical Library)

Self-Expression

Kenneth Dover, The Greeks, 3rd ed. (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1989), p. 62:

'Self-expression', a term which has no Greek equivalent, would have meant to the Greek artist the freedom to choose and dispose the elements which in combination satisfied the community's demand, or his patron's demand, for a particular theme to fulfil a particular social and religious function. The notion that self-expression is of any value in itself was quite alien to the Greeks. If the quality of the self which was being expressed was acknowledged to be high, they would be willing to give it a look or a hearing; but if it expressed itself in a style which was technically slovenly or insufficiently subjected to self-criticism, they would soon lose patience and say, 'Go away, and don't come back until you can express yourself in a way we can respect.'

Delusion

Aeschylus, Agamemnon 222-223 (tr. Herbert Weir Smyth):

On the sentence see Andrej Petrovic and Ivana Petrovic, Inner Purity and Pollution in Greek Religion, Vol. I: Early Greek Religion (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), pp. 136-138.

D.R. Shackleton Bailey dedicated two of his books to cats. The Petrovics' book is dedicated to their dog (p. ix):

For mankind is emboldened by wretched delusion, counsellor of ill, primal source of woe.παρακοπά (παρακοπή, "delusion") is the subject, from παρακόπτω, "strike awry." Both of the compound adjectives αἰσχρόμητις ("counselling shameful acts") and πρωτοπήμων ("bringing the start of sufferings") are hapax legomena. More literally, "For wretched delusion, counselling shameful acts, bringing the start of sufferings, emboldens mortals."

βροτοὺς θρασύνει γὰρ αἰσχρόμητις

τάλαινα παρακοπὰ πρωτοπήμων.

On the sentence see Andrej Petrovic and Ivana Petrovic, Inner Purity and Pollution in Greek Religion, Vol. I: Early Greek Religion (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), pp. 136-138.

D.R. Shackleton Bailey dedicated two of his books to cats. The Petrovics' book is dedicated to their dog (p. ix):

Woodrow Wilson is attributed with the following saying: 'If a dog will not come to you after having looked you in the face, you should go home and examine your conscience.' Over the past eight years our wonderful dog Mr Miyagi has been inspiring us in many ways to think about inner purity. Even though he has not penned a single word of this book, his help was nevertheless endless. Hence, in gratitude, we dedicate this book to Mr Miyagi, a true creature of ϕιλοϕροσύνη. Κύον πιστότατε, ϕρὴν καθαρωτάτη, σοὶ τόδε βιβλίον τίθεμεν.

Thursday, September 15, 2022

Hills and Woods

An Anthology of Sanskrit Court Poetry: Vidyākara's "Subhāṣitaratnakoṣa" translated by Daniel H.H. Ingalls (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1965 = Harvard Oriental Series, 44), p. 422 (number 1606):

Let be a kingdom of the earth with all its cares,

I value not, oh Lord, an universal empire at a straw.

My heart turns rather to the hills and woods

where herds of antelopes lie down in fearless sleep.

[ŚILHAṆA COLLECTION]

Against Our Enemies

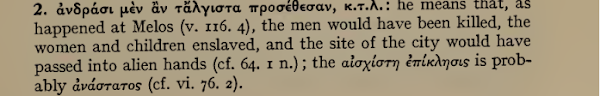

Thucydides 7.68.1-2 (speech of Gylippus; tr. Jeremy Mynott):

In the face, then, of such disarray and the failed fortunes of our bitterest enemies, let us engage them with real passion. Remember the general rule that against one's enemies you have a wholly legitimate right to satisfy your heart's desire in punishing the aggressor; such revenge, as the saying goes, is the sweetest of all pleasures and it is now within our grasp.A.W. Gomme et al. ad loc.:

That they are our enemies, and the worst of enemies, you all know: they came to our land to enslave us; and had they succeeded they would have inflicted the most terrible suffering on our men, gross indignities on our women and children, and on the city as a whole the ultimate brand of shame.

πρὸς οὖν ἀταξίαν τε τοιαύτην καὶ τύχην ἀνδρῶν ἑαυτὴν παραδεδωκυῖαν πολεμιωτάτων ὀργῇ προσμείξωμεν, καὶ νομίσωμεν ἅμα μὲν νομιμώτατον εἶναι πρὸς τοὺς ἐναντίους οἳ ἂν ὡς ἐπὶ τιμωρίᾳ τοῦ προσπεσόντος δικαιώσωσιν ἀποπλῆσαι τῆς γνώμης τὸ θυμούμενον, ἅμα δὲ ἐχθροὺς ἀμύνασθαι ἐκγενησόμενον ἡμῖν καὶ τὸ λεγόμενόν που ἥδιστον εἶναι.

ὡς δὲ ἐχθροὶ καὶ ἔχθιστοι, πάντες ἴστε, οἵ γε ἐπὶ τὴν ἡμετέραν ἦλθον δουλωσόμενοι, ἐν ᾧ, εἰ κατώρθωσαν, ἀνδράσι μὲν ἂν τἄλγιστα προσέθεσαν, παισὶ δὲ καὶ γυναιξὶ τὰ ἀπρεπέστατα, πόλει δὲ τῇ πάσῃ τὴν αἰσχίστην ἐπίκλησιν.

Wednesday, September 14, 2022

Counterclockwise

Karl Maurer, Interpolation in Thucydides (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1995 = Mnemosyne, Suppl., 150), p. 74, n. 28:

Perhaps it is just worth mentioning that Thucydidean catalogues seem often, for some reason, to proceed geographically in a counterclockwise spiral, towards the west and the south, to east and north east, ending in the far north west. Thus e.g., very consistently, much of the great list of allies at Syracuse in 7.57.James M. Scott, "Luke's Geographical Horizon," in David W.J. Gill and Conrad H. Gempf, edd., The Book of Acts in its First Century Setting, Vol. 2: Graeco-Roman Setting (1994; rpt. Eugene: Wipf and Stock Publishers, , 2000), pp. 483-544 (at 526):

1 Chronicles 1 lists the nations of the world 'in a circle' which proceeds counterclockwise—from the North, to the West, to the South, and to the East—with Jerusalem in the center.

Fame

Valerius Maximus, Memorable Doings and Sayings 8.14 ext. 3 (D.R. Shackleton Bailey):

Glory is not neglected even by such as attempt to inculcate contempt for it, since they are careful to add their names to those very volumes, in order to attain by use of remembrance what they belittle in their professions.John Briscoe, ed., Valerius Maximus, Facta et Dicta Memorabilia, Book 8: Text, Introduction, and Commentary (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2019), p. 219, provides no sources, but says:

ceterum gloria ne ab his quidem, qui contemptum eius introducere conantur, neglegitur, quoniam quidem ipsis voluminibus nomina sua diligenter adiciunt, ut quod professione elevant usurpatione memoriae adsequantur.

V. somewhat bizarrely implies that those who professed to despise glory should have published their books anonymously or under a pseudonym.The sentiment wasn't unique to Valerius Maximus. Cf. Cicero, In Defense of Archias 26:

Philosophers themselves, even in the books which they write about despising fame, sign their own names.and Cicero, Tusculan Disputations 1.14.34:

ipsi illi philosophi, etiam in iis libellis quos de contemnenda gloria scribunt, nomen suum inscribunt.

Do not our philosophers, in the very books which they write about despising fame, sign their own names?See also Tacitus, Histories 4.6:

nostri philosophi nonne in iis libris ipsis, quos scribunt de contemnenda gloria, sua nomina inscribunt?

Even by wise men the desire for fame is laid aside last of all.

etiam sapientibus cupido gloriae novissima exuitur.

Tuesday, September 13, 2022

He Is Still There When I Come Back to Him

Kenneth Dover, The Greeks, 3rd ed. (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1989), pp. 34-35, with note on p. 136:

Thucydides describes this critical battle:The Greek:When the Athenians came up against the barrier, with the impetus of that first onslaught they overpowered the ships stationed in front of the barrier and tried to break through what held them in. Thereupon the Syracusans and their allies bore down on them from every quarter; and now the fighting was no longer only at the barrier, but in every part of the harbour.29I suppose that by now I must have read this part of Thucydides' text more than a hundred times; I have published a commentary on books vi and vii, which involved me in some six thousand hours of work altogether, much of it on the minutiae of chronology, grammar, and textual criticism (for example, I once looked up all six hundred examples of a certain common preposition in the whole of Thucydides in order to elucidate the precise sense of one passage). Yet I still cannot read the words 'thereupon the Syracusans and their allies bore down on them from every quarter' without feeling the hair on the back on my neck stand on end, as when in a war-film a great attacking force suddenly begins to move, full of vengeful confidence. Perhaps that is why I don't mind interrupting Thucydides to talk about prepositions and the like. He is still there when I come back to him.

29. Thucydides vii 70.2 ...

ἐπειδὴ δὲ οἱ ἄλλοι Ἀθηναῖοι προσέμισγον τῷ ζεύγματι, τῇ μὲν πρώτῃ ῥύμῃ ἐπιπλέοντες ἐκράτουν τῶν τεταγμένων νεῶν πρὸς αὐτῷ καὶ ἐπειρῶντο λύειν τὰς κλῄσεις· μετὰ δὲ τοῦτο πανταχόθεν σφίσι τῶν Συρακοσίων καὶ ξυμμάχων ἐπιφερομένων οὐ πρὸς τῷ ζεύγματι ἔτι μόνον ἡ ναυμαχία, ἀλλὰ καὶ κατὰ τὸν λιμένα ἐγίγνετο.

Monday, September 12, 2022

Apples

Christopher Morley (1890-1957), Mince Pie: Adventures on the Sunny Side of Grub Street (New York: George H. Doran Company, 1919), pp. 171-173:

As we walked homeward under a frosty sparkle of sky we mused upon all the different kinds of apples we have encountered. There are big glossy green apples and bright red apples and yellow apples and also that particularly delicious kind (whose name we forget) that is the palest possible cream color—almost white. We have seen apples of strange shapes, something like a pear (sheepnoses, they call them), and the Maiden Blush apples with their delicate shading of yellow and debutante pink. And what a poetry in the names—Winesap, Pippin, Northern Spy, Baldwin, Ben Davis, York Imperial, Wolf River, Jonathan, Smokehouse, Summer Rambo, Rome Beauty, Golden Grimes, Shenango Strawberry, Benoni!Related post: Imperfections.

We suppose there is hardly a man who has not an apple orchard tucked away in his heart somewhere. There must be some deep reason for the old suspicion that the Garden of Eden was an apple orchard. Why is it that a man can sleep and smoke better under an apple tree than in any other kind of shade? Sir Isaac Newton was a wise man, and he chose an apple tree to sit beneath. (We have often wondered, by the way, how it is that no one has ever named an apple the Woolsthorpe after Newton's home in Lincolnshire, where the famous apple incident occurred.)

An apple orchard, if it is to fill the heart of man to the full with affectionate satisfaction, should straggle down a hillside toward a lake and a white road where the sun shines hotly. Some of its branches should trail over an old, lichened and weather-stained stone wall, dropping their fruit into the highway for thirsty pedestrians. There should be a little path running athwart it, down toward the lake and the old flat-bottomed boat, whose bilge is scattered with the black and shriveled remains of angleworms used for bait. In warm August afternoons the sweet savor of ripening drifts warmly on the air, and there rises the drowsy hum of wasps exploring the windfalls that are already rotting on the grass. There you may lie watching the sky through the chinks of the leaves, and imagining the cool, golden tang of this autumn's cider vats.

Excisions

William Wyse, The Speeches of Isaeus (Cambridge: At the University Press, 1904), pp. xl-xli:

S.A. Naber and H. van Herwerden following the lead of their illustrious master, Cobet, ply the knife without mercy. Apparently they think it sound criticism to excise everything which is not indispensable to a trained scholar scrutinising a speech in his study.

Smitten

Chariton, Callirhoe 2.4.3 (tr. G.P. Goold; he = Dionysius; her, she = Callirhoe):

In his mind he was at the shrine of Aphrodite, and he recalled every detail: her face, her hair, how she had turned round and looked at him, her voice, her figure, her words; her very tears were setting him on fire.

ὅλος δὲ ἦν ἐν τῷ τῆς Ἀφροδίτης ἱερῷ καὶ πάντων ἀνεμιμνήσκετο, τοῦ προσώπου, τῆς κόμης, πῶς <ἐπ>εστράφη, πῶς ἐνέβλεψε, τῆς φωνῆς, τοῦ σχήματος, τῶν ῥημάτων· ἐξέκαε δὲ αὐτὸν καὶ τὰ δάκρυα.

Sunday, September 11, 2022

Prayer

An Anthology of Sanskrit Court Poetry: Vidyākara's "Subhāṣitaratnakoṣa" translated by Daniel H.H. Ingalls (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1965 = Harvard Oriental Series, 44), pp. 421-422 (number 1605):

I pray that I may have before me songsters,

beside me tasteful poets from the South

and behind me girls whose graceful bracelets

jingle as they wave the flywhisk.

If this should be, be greedy, heart,

to taste the world.

If it, however, should not be,

then enter highest brahma.

UTPALARĀJA [BHARTṚHARI COLLECTION]

Rejuvenation

Aristophanes, Frogs 341-349 (chorus of initiates; tr. Stephen Halliwell):

Iakchos, hail Iakchos,Alan H. Sommerstein ad loc.:

Our light-bringing star for nocturnal rites!

The meadow blazes with flames of gleaming torches.

Even old men's knees flex in dance.

They shake off all their cares

And the heavy weight of copious years

To join the sacred worship.

Ἴακχ᾽ ὦ Ἴακχε,

νυκτέρου τελετῆς φωσφόρος ἀστήρ.

φλογὶ φέγγεται δὲ λειμών·

γόνυ πάλλεται γερόντων· 345

ἀποσείονται δὲ λύπας

χρονίους τ᾽ ἐτῶν παλαιῶν ἐνιαυτοὺς

ἱερᾶς ὑπὸ τιμᾶς.

343 brilliant star of our nocturnal rites: cf. Soph. Ant. 1146-8 (of Dionysus-Iacchus) "leader of the dance of the stars breathing fire, master of the voices heard by night" (tr. Lloyd-Jones).Plato, Laws 2.666b-c (tr. R.G. Bury):

345-9 old men's knees leap ... thanks to thy holy worship: likewise in Eur. Ba. 188-190 the power of Dionysus makes old men forget their years (cf. Pl. Laws 666b), and rejuvenation is a recurrent theme of Old Comedy too (e.g. Knights 1321ff, Wasps 1066-7, 1299ff, Peace 349-353, Lys. 667-671, Eccl. 848-850), often taking the form of the recovery of sexual potency by an old man (Dicaeopolis, Demos, Philocleon, Trygaeus, Peisetaerus, Blepyrus).