Sunday, July 31, 2022

Of Men and Mice

Boethius, Consolation of Philosophy 2.6.4 (tr. P.G. Walsh):

And what is this desirable, glorious power which you men seek? Being living creatures of the earth, you presumably give thought to those you see as your subjects, and to your own role as masters? Imagine your reaction if you saw a colony of mice, and one of them was claiming lawful dominion over the rest; that would be good for a belly-laugh!

quae vero est ista vestra expetibilis ac praeclara potentia? nonne, o terrena animalia, consideratis quibus qui praesidere videamini? nunc si inter mures videres unum aliquem ius sibi ac potestatem prae ceteris vindicantem, quanto movereris cachinno!

Home of Eber and Raps

Thanks to Eric Thomson for these photographs of the so-called Temple of Concordia in Agrigento, Sicily:

Mauro Serìo and Chiara Niccoli, edd., The Valley of the Temples of Agrigento and Heraclea Minoa: Guide, tr. Sylvia Notini (Milan: Skira, 2018), pp. 26-27, 32-33:

From the Temple of Juno, head down the Via dei Templi in a westward direction and you'll reach the so-called Temple of Concordia. The identification is actually false and was formulated on the basis of a marble inscription from the first Roman imperial period (mid-1st century AD) with a dedication in Latin that reads CONCORDIAE AGRIGENTINORUM SACRUM [...]. The inscription, now preserved in the "Pietro Griffo" Regional Archaeological Museum, was observed in Agrigento by the Dominican historian and theologian Tommaso Fazello (1498-1570), who related it to a "temple not far from that of Hercules" in De Rebus Siculis decades duae.The inscription is Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum X 7192:

Since then, the temple has been indicated as dedicated to Concordia, in spite of the fact that scholars have for some time now held that the inscription is unrelated to it, and should instead be referred to a lost artefact, perhaps a statue or an altar. The deity to which the edifice, which was built in the second half of the 5th century BC, was originally dedicated is still unknown today. Many hypotheses have been advanced by the experts, none of which has been proven; nonetheless, they all have one element in common, that is, they identify two gods as having been destined for worship. Hence, the Dioscuri, the twins Castor and Pollux, sons of Leda and Zeus (in Greek Dioscuri means "sons of Zeus", the Jupiter of the Romans), at times Hercules and Mercury, at others Hercules and Triptolemus. It is also worthy of note that a double dedication is suggested for the temple, not so much based on the events that involved the building in ancient times (which we have no knowledge of), but rather on those that occurred later when, in the late 6th century AD, the temple was turned into a Christian church consecrated to Saints Peter and Paul. The artificer of this transformation and ensuing dedication was Gregory, Bishop of Agrigento from 591 to 630, after he had liberated the ancient building from the demons of Eber and Raps, who had chosen to dwell in the temple, as reported by the monk Leontius in Vita del vescovo agrigentino Gregorio (Life of Saint Gregory, Bishop of Agrigento). In essence, there are some scholars who, going back in time, wonder if there could be a relationship berween the dedication to two saints, Peter and Paul, and the older one, as would be suggested by the news of the pair of demons expelled by the bishop. As we await further discoveries to be made, the large and best-preserved temple on the hill of ancient Agrigento continues to be described as dedicated to Concordia.

Built between 440 and 430 BC from local limestone, the Doric temple (19.75 x 42.23 metres) rises up on a tall four-step crepidoma, which in turn lies on a massive foundation created to even out the earth below it. The temple has six columns on each of its short sides, and thirteen on each of its long ones. Each column has a shaft that tapers at the top, and is characterized by twenty flutes and four drums, the lowest one of these set directly on the stylobate. Each column, including the capital, reaches a height of almost seven metres.

Unique among the temples of Agrigento, its entablature is intact, formed by a smooth architrave and a frieze that is clearly recognizable from the typical alternating metopes (sixty-eight in number) and triglyphs (seventy-two in number), an element typical of the Doric order. Furthermore, note how the metopes and the triglyphs located at the farthest ends of the four friezes, are wider (1.67 metres) than the others: this is so as to solve the so-called "corner conflict" (a problem typical of Doric architecture related to the need to structurally and visually reinforce the points of contact between the different segments of the entablature). On the short sides, above the frieze, the horizontal cornice (called geison in Greek) projects outwards, together with the two oblique cornices framing the tympanum, thus constituting the pediment. The total absence of any trace of supports both inside the metopes of the frieze, and outside the two tympana on the pediments, has led to the hypothesis that they were all devoid of a sculptural decoration. Clearly visible is the fact that the columns are not perfectly vertical, but rather inclined a few millimetres inwards towards the monument; also visible at a third of the height of each shaft is a slight swelling (or entasis). Lastly, each intercolumniation (the space between the columns) gradually narrows from the centre to the corners of the peristasis, thereby creating a particular optical effect that makes up for the distorted vision of the temple when it is observed from a distance. After entering the temple and crossing the ambulatory, you reach the cella, which is set on a base with one step leading up to it. This is divided into a pronaos, a naos and an opisthodomos, the first and last distili in antis (that is, each with two columns situated between the antae). In the pronaos, to either side of the entrance to the naos, two pylons rise up inside which two flights of stairs were built, making it possible to climb up to the roof of the sacred building to carry out maintenance work. Nothing remains of the roof which was traditionally double-gabled, supported by wooden trusses, and covered with terracotta tiles. As for the naos and the opisthodomos, these two spaces, which in ancient times were never connected, were instead made into a single space to allow for entry from the west when Gregory, Bishop of Agrigento, transformed the temple into a church in the late 6th century. In addition to reorienting the entrance to the building, the intercolumniation of the outer colonnade was walled shut, while six round arches were made in the masonry of the long sides of the naos. Hence, the entire building now resembled a church, characterized by the division of the internal space into three naves. This new use was recorded until 1748, when the church was deconsecrated. Later, in 1788, thanks to the intervention of the Prince of Torremuzza authorized by the Bourbons, the space between the columns of the peristasis was freed, and the original appearance of the exterior of the building was restored, while inside the ancient naos the side arches were left intact. Still today, they constitute an evident trace of the transformation of the ancient temple into a church. To this regard, we should not overlook the fact that we owe this 5th-century-BC temple's exceptional state of conservation to its repurposing. That could explain why, in May 2005, the Catholic Church Congregation for Divine Worship proclaimed Saint Gregory II of Agrigento (Bishop Gregory rose to the honour of the altars in the 15th century) patron saint of conservators of archaeological and architectural heritage.

Concordiae Agrigentinorum sacrum res publica Lilybitanorum dedicantibus M(arco) Haterio Candido proco(n)s(ule) et L(ucio) Cornelio Marcello q(uaestore) pr(o) pr(aetore)Here is an image of the inscription: On Eber and Raps see Wilhelm Alzinger, "Raps, Eber und der Concordiatempel in Akragas," Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 14 (1974) 295-299.

People in High Places

Salvian, On the Governance of God 4.4.21 (tr. Jeremiah F. O'Sullivan):

As regards people in high places, of what does their dignity consist but in confiscating the property of the state? As regards some whose names I do not mention, what is a political position, but a kind of plunder? There is no greater pillaging of poor states than that done by those in power. For this, office is bought by the few to be paid for by ravaging the many. What can be more disgraceful and wicked than this? The poor pay the purchase price for positions which they themselves do not buy. They are ignorant of the bargain, but know the amount paid. The world is turned upside down that the light of a few may become illustrious. The elevation of one man is the downfall of all the others.I would remove "the light of" from the translation.

quid est enim aliud dignitas sublimium quam proscriptio civitatum? aut quid aliud quorundam, quos taceo, praefectura quam praeda? nulla siquidem maior paupercularum est depopulatio quam potestas; ad hoc enim honor a paucis emitur, ut cunctorum vastatione solvatur: quo quid esse indignius quid iniquius potest? reddunt miseri dignitatum pretia, quas non emunt: commercium nesciunt et solutionem sciunt: ut pauci inlustrentur, mundus evertitur: unius honor orbis excidium est.

Sounding the Alarm

J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings, Part 3: The Return of the King (VI.8: The Scouring of the Shire):

Then he heard Merry change the note, and up went the Horn-cry of Buckland, shaking the air.

Awake! Awake! Fear, Fire, Foes! Awake!

Fire, Foes! Awake!

Saturday, July 30, 2022

The Best Part of Life?

Thomas Mann, The Magic Mountain, chapter 3 (Hans Castorp speaking; tr. James E. Woods):

I don't understand how someone can not be a smoker—why it's like robbing oneself of the best part of life, so to speak, or at least of an absolutely first-rate pleasure. When I wake up I look forward to being able to smoke all day, and when I eat, I look forward to it again, in fact I can honestly say that I actually only eat so that I can smoke, although that's an exaggeration, of course. But a day without tobacco—that would be absolutely insipid, a dull, totally wasted day. And if some morning I had to tell myself: there's nothing left to smoke today, why I don't think I'd find courage to get up, I swear I'd stay in bed.

Ich verstehe es nicht, wie jemand nicht rauchen kann, — er bringt sich doch, sozusagen, um des Lebens bestes Teil und jedenfalls um ein ganz eminentes Vergnügen! Wenn ich aufwache, so freue ich mich, daß ich tagüber werde rauchen dürfen, und wenn ich esse, so freue ich mich wieder darauf, ja ich kann sagen, daß ich eigentlich bloß esse, um rauchen zu können, wenn ich damit natürlich auch etwas übertreibe. Aber ein Tag ohne Tabak, das wäre für mich der Gipfel der Schalheit, ein vollständig öder und reizloser Tag, und wenn ich mir morgens sagen müßte: heut gibt's nichts zu rauchen, — ich glaube, ich fände den Mut gar nicht, aufzustehen, wahrhaftig, ich bliebe liegen.

Enjoy

Greek Anthology 11.51 (tr. W.R. Paton):

Enjoy the season of thy prime; all things soon decline:Related post: The Apolausticks.

one summer turns a kid into a shaggy he-goat.

τῆς ὥρας ἀπόλαυε· παρακμάζει ταχὺ πάντα·

ἓν θέρος ἐξ ἐρίφου τρηχὺν ἔθηκε τράγον.

Replacement

Susanna Morton Braund, ed., Juvenal, Satires, Book I (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), pp. 183-184 (on 3.58-125):

Umbricius' next complaint is that true Romans have been displaced by foreigners. This section is an extravaganza of xenophobia directed chiefly against the Greeks of the eastern Mediterranean (hence the numerous Greek names and nouns: 61, 62, 63, 64, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 7 4, 76, 77, 81, 98, 99, 100, 103, 115, 118, 120; cf. sarcastic Graeculus 78), with a side-swipe at Semites (62-6, introduced by Syrus . . . Orontes, developing from the prologue, 13-14). This standard theme in satirical attacks on the city has parallels in Lucilius (e.g. a Syrophoenician 540-1 W, a Syrian 652-3 W, a Hellenomaniac 87-93W), Horace (e.g. Sat. 2.2.11) and Persius (e.g. 1.70, 6.38-40). It should not be taken as evidence for Trajanic/Hadrianic Rome, in which Greeks were much better integrated than some other foreign groups whose arrival was more recent; for a different view, however, from a Greek perspective see Lucian De merc cond. Athenaeus at Deipn. 1.20b-c praises Rome as an epitome of the civilised world: 'Even entire nations are settled there en masse, like the Cappadocians, the Scythians, the Parthians, and more besides.'

An Unenlightened Mind

Russell Kirk, Confessions of a Bohemian Tory: Episodes and Reflections of a Vagrant Career (New York: Fleet Publishing Corporation, 1963), p. 23:

Mine was not an Enlightened mind, I now was aware: it was a Gothic mind, medieval in its temper and structure. I did not love cold harmony and perfect regularity of organization; what I sought was variety, mystery, tradition, the venerable, the awful. I despised sophisters and calculators; I was groping for faith, honor, and prescriptive loyalties. I would have given any number of neo-classical pediments for one poor battered gargoyle. The men of the Enlightenment had cold hearts and smug heads; now their successors were in the process of imposing a dreary conformity upon all the world, with Efficiency and Progress and Equality for their watchwords—abstractions preferred to all those fascinating and lovable peculiarities of human nature and human society which are the products of prescription and tradition.

Who Appointed You Judge?

Salvian, On the Governance of God 4.2.12 (tr. Jeremiah F. O'Sullivan):

From this it can be realized how wickedly and improperly severe we are on others, but how indulgent with ourselves. We are most harsh to others, most lenient with ourselves. We punish others, but forgive ourselves for the same crime— an act of intolerable arrogance and presumption. We are unwilling to acknowledge guilt in ourselves, but we dare to arrogate to ourselves the right to judge others. What can be more unjust and what more perverse?

hinc ergo agnosci potest, quam inique ac pravissime aliis severissimi sumus, nobis indulgentissimi; aliis asperi, nobis remissi. in eodem crimine punimus alios, nos absolvimus: intolerabilis prorsus et contumaciae et praesumptionis. nec agnoscere volumus in nobis reatum et audemus de aliis usurpare iudicium. quid esse iniustius nobis aut quid perversius potest?

Friday, July 29, 2022

Self-Deception

Galatians 6:3 (KJV):

For if a man think himself to be something, when he is nothing, he deceiveth himself.Hans Dieter Benz ad loc.:

εἰ γὰρ δοκεῖ τις εἶναί τι μηδὲν ὤν, φρεναπατᾷ ἑαυτόν.

The form as well as content of this sententia are known from the diatribe literature, and even from Plato.76 Two examples from Epictetus may suffice as illustrations: κἂν δόξῃς τις εἶναί τισιν͵ ἀπίστει σεαυτῷ ("and if you think you are somebody for some, distrust yourself");77 and δοκεῖς τις εἶναι, μωρὸς παρὰ μωροῖς ("you think you are somebody—fool among fools!").78 Another example from Lucian shows the anti-rhetorical background of the saying: σκόπει γοῦν ὁπόσοι τέως μηδὲν ὄντες ἔνδοξοι καὶ πλούσιοι καὶ νὴ Δία εὐγενέστατοι ἔδοξαν ἀπὸ τῶν λόγων ("just look how many who previously were nobodies have come to be famous and rich, and by God, even noblemen, all from their eloquence").79

The contrast between what one "appears to be" and what one "really is" was a standard topic of diatribe philosophy,80 from which the language used here comes. Paul sees in the "pneumatics" this very danger of believing oneself to be something of importance, while in reality one is "nothing." It is probably no accident that we find similar sayings at several places in 1 Corinthians (3:18; 8:2; 10:12; 14:37).81 There is nothing wrong with being "nothing" or a "nobody," because that is what one actually is. It is wrong, however, to be deluded into thinking one is "somebody." The anthropological tradition in which Paul stands goes back to early Greek thought. Usually we find it in the diatribe tradition82 in connection with the interpretation of the Delphic maxim "know yourself." Human beings must learn to accept that they really are "nothing."83 Applied to 6:3, Paul tells the Galatians: if you think you are "pneumatics" but are not, you are caught up in a dangerous and preposterous illusion. The verb φρεναπατάω ("deceive") is a hapax legomenon in primitive Christian literature.84 Hesychius85 gives as a synonym χλευάζω ("scoff at somebody"), but the meaning here might not be much different from 1 Cor 3:18: μηδεὶς ἑαυτὸν ἐξαπατάτω ("let no one deceive himself"); or from Jas 1:26: ἀπατῶν καρδίαν ἑαυτοῦ ("deceive one's own heart").86

76 See Plato Apol. 21B/C, 41B, E, and often.

77 Ench. 13; cf. also the anecdote about Socrates Diss. 2.8.24f; 4.6.24; Ench. 33.12; 48.2-3. Cf. R. Hillel, "Do not trust yourself until the day you die" ('Abot 2.5).

78 Diss. 4.8.39.

79 Lucian Rhet. praec. 2; cf. Merc. cond. 16; Dial. mort. 12.2, and often.

80 See Teles' diatribe Περὶ τοῦ δοκεῖν καὶ τοῦ εἶναι ("About appearing and being") in Teletis Reliquiae, Frag. I (ed. Otto Hense (Tübingen: Mohr,2 1909]); Chadwick, Sextus, 64. A similar saying in Midr. Qoh. 9.10 (42b) (see Str-B. 3.578) from the 3rd. c. A.D. could point to diatribe influence upon the rabbis.

81 The closest parallel is I Cor 3:18, but contrast Phil 3:4; cf. Jas 1:26.

82 See the bib. above; also Chadwick, Sextus, 97ff.

83 Cf. Paul's "confession" 2 Cor 12:11: οὐδέν εἰμι ("I am nothing"); for the interpretation of this doctrine, see Betz, Paulus, 118ff. For more references see Wettstein on Gal 6:3.

84 For later instances in Christian literature, see PGL, s.v. The noun φρεναπάτης (LSJ, s.v.: "soul-deceiver") occurs in Titus 1:10. Cf. also Bauer, s.v.

85 Lexicon (ed. Mauricius Schmidt, vol. 3; Jena: Sumptibus Frederici Maukii, 1861) 257, no. 57.

86 Cf. also Epicurus' phrase ταῖς κεναῖς δόξαις ἑαυτὸν ἀπατᾶν ("deceive oneself by empty opinions") 298, 29 Usener; and the term κενόδοξος ("boastful") in Gal 5:26.

The History of a Lost Cause

Richard Weaver (1910–1963), "Up From Liberalism," Modern Age 3 (Winter 1958–1959) 22-32 (at 25):

I am now further convinced that there is something to be said in general for studying the history of a lost cause. Perhaps our education would be more humane in result if everyone were required to gain intimate acquaintance with some coherent ideal that failed in the effort to maintain itself. It need not be a cause which was settled by war; there are causes in the social, political, and ecclesiastical worlds which would serve well. But it is good for everyone to ally himself at one time with the defeated and to look at the "progress" of history through the eyes of those who were left behind. I cannot think of a better way to counteract the stultifying "Whig" theory of history, with its bland assumption that every cause which has won has deserved to win, a kind of pragmatic debasement of the older providential theory. The study and appreciation of a lost cause have some effect of turning history into philosophy. In sufficient number of cases to make us humble, we discover good points in the cause which time has erased, just as one often learns more from the slain hero of a tragedy than from some brassy Fortinbras who comes in at the end to announce the victory and proclaim the future disposition of affairs.

Thursday, July 28, 2022

The Life of Study

A.G. Sertillanges (1863-1948), The Intellectual Life, tr. Mary Ryan (Westminster: The Newman Press, 1960), p. 4:

The life of study is austere and imposes grave obligations. It pays, it pays richly; but it exacts an initial outlay that few are capable of. The athletes of the mind, like those of the playing field, must be prepared for privations, long training, a sometimes superhuman tenacity. We must give ourselves from the heart, if truth is to give itself to us. Truth serves only its slaves.

That Passed, This Can Too

Tom Shippey, The Road to Middle-Earth, rev. ed. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2003), p. 328:

I would say that what hangs over the end of all Tolkien's fiction is not 'And so they all lived happily ever after', but the line from the Old English poem Déor, þæs ofereode, þisses swa mæg. This could be translated bluntly, 'That passed, this can too', but Tolkien translated it — see BLT 2, p. 323, for its importance to him and his writing — 'Time has passed since then, this too can pass'.BLT = The Book of Lost Tales, where Christopher Tolkien wrote:

In the great Anglo-Saxon manuscript known as the Exeter Book there is a little poem of 42 lines to which the title of Déor is now given. It is an utterance of the minstrel Déor, who, as he tells, has lost his place and been supplanted in his lord's favour by another bard, named Heorrenda; in the body of the poem Déor draws examples from among the great misfortunes recounted in the heroic legends, and is comforted by them, concluding each allusion with the fixed refrain þæs ofereode; þisses swa mæg, which has been variously translated; my father held that it meant 'Time has passed since then, this too can pass'.Kemp Malone, ed., Déor, 3rd ed. (London: Methuen & Co Ltd, 1961), pp. 23-24:

G. Shipley, Gen. Case p. 18, explains þæs and þisses as instrumental genitives, or, alternatively, genitives of measure, but it seems better to call them genitives of reference, or respect. Oferēode is used impersonally; see Shipley pp. 18 and 50. Ofergän is to be understood after mæg.Morton W. Bloomfield, "The Form of Deor," PMLA 79.5 (December, 1964) 534-541 (at 535, where "lines" = the repeated refrain):

There have been possibly over a hundred different translations—as has been estimated—for these lines. It seems hard to believe that these five words of rather simple OE should give rise to so many variant translations, but it is nevertheless true.Id. (at 536):

Literally then the words mean "in respect to that it passed away; in respect to this it likewise can or will (pass away).".... I render the whole refrain, polishing the literal translation, as "That passed away; so will ("shall" or "can") this."Craig Williamson translated the refrain as "That passed over—so can this." Here are some lines from Déor without the refrain, translated by Williamson:

A man sits alone in the clutch of sorrow,I haven't yet looked at:

Separated from joy, thinking to himself

That his share of suffering is endless.

The man knows that all through middle-earth,

Wise God goes, handing out fortunes,

Giving grace to many—power, prosperity,

Wisdom, wealth—but to some a share of woe.

- Theodor von Grienberger, "Deor," Anglia 45 (1921) 398-399

- Knud Schibsbye, "þæs ofereode, þisses swa mæg," English Studies 50 (1969) 380-381

- Murray F. Markland, "Deor: þæs ofereode, þisses swa mæg," American Notes and Queries 3 (November, 1972) 35-36

- Jon Erickson, "The Deor Genitives," Archivum Linguisticum n.s. 6 (1975) 77-84

- Gwang-Yoon Goh, "Genitive in Deor: Morphosyntax and Beyond," Review of English Studies 52 (2001) 485-499

Wednesday, July 27, 2022

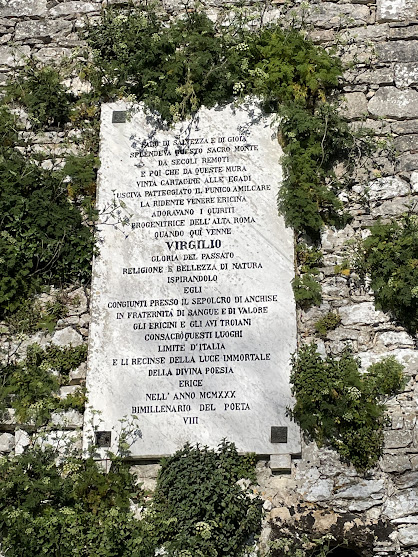

An Inscription at Erice

Thanks to Eric Thomson for sending me this photograph of an Italian inscription from Erice, Sicily, composed by Giuseppe Pagoto and erected in 1930:

Here is a mixed-case transcription with my tentative punctuation (line numbers also added):

Faro di salvezza e di gioia,Here is my very rough first attempt at a translation:

splendeva questo sacro monte,

da secoli remoti

e poi che da queste mura,

vinta Cartagine alle Egadi, 5

usciva patteggiato il punico Amilcare.

La ridente Venere Ericina

adoravano i Quiriti,

progenitrice dell'alta Roma,

quando quì venne 10

Virgilio,

gloria del passato,

religione e bellezza di natura

ispirandolo

egli. 15

Congiunti presso il sepolcro di Anchise

in fraternità di sangue e di valore

gli Ericini e gli avi Troiani.

Consacrò questi luoghi,

limite d'Italia, 20

e li recinse della luce immortale

della divina poesia.

Erice,

nell' anno MCMXXX,

bimillenario del poeta, 25

VIII.

Beacon of salvation and joyA few notes:

this holy mountain gleamed

from centuries remote

and then when from these walls

(Carthage having been defeated at the [Battle of the] Aegates)

the Punic Hamilcar came forth to sue for peace.

The Quirites worshipped

the laughing Venus Erycina,

ancestress of lofty Rome,

when hither came

Vergil,

glory of the past,

religion and beauty of nature

inspiring him.

Joined together at the tomb of Anchises,

in brotherhood of blood and valor,

(were) the inhabitants of Erice and the Trojan ancestors.

He (Vergil) consecrated these places,

outpost of Italy,

and surrounded them with the immortal light

of divine poetry.

At Erice

in the year MCMXXX,

bimillennary of the poet,

(year) VIII (of the Fascist Era).

5 vinta Cartagine alle Egadi — the Battle of the Aegates (241 B.C.) marked the end of the First Punic War.Related post: Hail!

7 la ridente Venere Ericina — cf. Horace, Odes 1.2.33: Erycina ridens.

16-17 Congiunti ... gli Ericini e gli avi Troiani — cf. Vergil, Aeneid 5.293: undique conveniunt Teucri mixtique Sicani (at the funeral games for Aeneas' father Anchises).

Riddles of Pythagoras

Athenaeus 10.452d-e (tr. Charles Burton Gulick):

The riddles of Pythagoras, again, are of such a kind as the following, as Demetrius of Byzantium says in the fourth book On Poetry: 'Eat not thy heart,' instead of 'Cultivate apathy to pain.' 'Poke not the fire with a knife,' instead of 'Wrangle not with an angry man'; for anger is fire, and wrangling is a knife. 'Step not over the beam of the balance,' instead of 'Avoid and hate all mean advantage, and seek for equality.' 'Walk not on the main-travelled roads' instead of 'Follow not the opinion of the many'; for every man answers too rashly, as it happens to please him; but one should go the straight road, using reason as his guide. 'Sit not over a quart-measure,' instead of 'Consider not merely the things of to-day, but be ready for the day to come.' 'When on a journey turn not back at the boundaries'; for the bounds and limit of life is death; death, then, he forbids us to approach with pain and worry.

καὶ τὰ Πυθαγόρου δὲ αἰνίγματα τοιαῦτά ἐστιν, ὥς φησι Δημήτριος ὁ Βυζάντιος ἐν τετάρτῳ περὶ ποιημάτων· 'καρδίαν μὴ ἐσθίειν' ἀντὶ τοῦ ἀλυπίαν ἀσκεῖν. 'πῦρ μαχαίρᾳ μὴ σκαλεύειν' ἀντὶ τοῦ τεθυμωμένον ἄνδρα μὴ ἐριδαίνειν· πῦρ γὰρ ὁ θυμός, ἡ δὲ ἔρις μάχαιρα. 'ζυγὸν μὴ ὑπερβαίνειν' ἀντὶ τοῦ πᾶσαν πλεονεξίαν φεύγειν καὶ στυγεῖν, ζητεῖν δὲ τὸ ἴσον. 'λεωφόρους ὁδοὺς μὴ στείχειν' ἀντὶ τοῦ γνώμῃ τῶν πολλῶν μὴ ἀκολουθεῖν· εἰκῇ γὰρ ἕκαστος ὅ τι ἂν δόξῃ ἀποκρίνεται· τὴν δ᾽ εὐθεῖαν ἄγειν ἡγεμόνι χρώμενον τῷ νῷ. 'μὴ καθῆσθαι ἐπὶ χοίνικα' ἀντὶ τοῦ μὴ σκοπεῖν τὰ ἐφ' ἡμέραν, ἀλλὰ τὴν ἐπιοῦσαν ἀεὶ προσδέχεσθαι. 'ἀποδημοῦντα ἐπὶ τοῖς ὅροις μὴ ἐπιστρέφεσθαι'· ὅρια γὰρ καὶ πέρας ζωῆς ὁ θάνατος· τοῦτον οὖν οὐκ ἐᾷ μετὰ λύπης καὶ φροντίδος προσίεσθαι.

That Most Lovely and Loveable Country

Samuel Butler, Alps and Sanctuaries of Piedmont and the Canton Ticino (London: David Bogue, 1882), p. 4:

Via Samuel Butler, Erice, Sicily

Hat tip: Eric Thomson.

But who does not turn to Italy who has the chance of doing so? What, indeed, do we not owe to that most lovely and loveable country? Take up a Bank of England note and the Italian language will be found still lingering upon it. It is signed "for Bank of England and Compa." (Compagnia), not "Compy." Our laws are Roman in their origin. Our music, as we have seen, and our painting comes from Italy. Our very religion till a few hundred years ago found its headquarters, not in London nor in Canterbury, but in Rome. What, in fact, is there which has not filtered through Italy, even though it arose elsewhere?

Hat tip: Eric Thomson.

Tuesday, July 26, 2022

Asyndetic Triplets with Privative Prefixes

Calvert Watkins (1933-2013), How to Kill a Dragon: Aspects of Indo-European Poetics (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), p. 113:

The figure of anaphora, repetition of a sound, word, or phrase at the beginning of successive verses or other units is very common in Vedic. RV 8.70.11 combines a phonetic anaphora in a(nya-) 'other-' and a(va) 'off with a semantic one in a- 'un-', and concludes with the repetition of the same word at the end of pādas c and d, a sort of 'cataphora' known as punaḥpadam (chap. 4 n.8), which runs through 6 verses of the hymn. The strophe is bṛhatī, 8/8/12/8 syllables:I don't have access to J.N. Adams, Asyndeton and its Interpretation in Latin Literature: History, Patterns, Textual Criticism (Cambridge University Press, 2021), but I extracted the following images from a digital copy on Google Books (pp. 99-102 in the hard copy book, I think):anyávratam ámānuṣamFor the anaphora of privative compounds of similar semantics compare Il. 9.63-4:

áyajvānam ádevayum

áva sváḥ sákhā dudhuvīta párvataḥ

sughnā́ya dásyum párvataḥ

Him who follows another commandment, the non-man,

non-worshipping godless one,

may his (your?) friend the mountain shake down,

the mountain the barbarian, the easier to slay.ἀφρήτωρ ἀθέμιστος ἀνέστιός ἐστιν ἐκεῖνοςThis figure can be securely posited for the poetic grammar of the protolanguage.

ὃς πολέμου ἔραται ἐπιδημίου ὀκρυόεντος.

Clanless, lawless, hearthless is he

that lusts for chilling war among his own people.

Labels: asyndetic privative adjectives

Fruitless and Futile

Salvian, On the Governance of God 3.1.5 (tr. Jeremiah F. O'Sullivan):

It is fruitless and futile labor where a perverse listener will not accept proofs.

infructuosus quippe est et inanis labor, ubi non recipit probationem pravus auditor.

Monday, July 25, 2022

Men and Beasts

Greek Anthology 11.46 (by Automedon [or Antimedon] of Cyzicus; tr. tr. W.R. Paton):

We are men in the evening when we drink together, but when day-break comes, we get up wild beasts preying on each other.

ἄνθρωποι δείλης, ὅτε πίνομεν· ἢν δὲ γένηται

ὄρθρος, ἐπ᾽ ἀλλήλους θῆρες ἐγειρόμεθα.

Temptation

A.G. Sertillanges (1863-1948), The Intellectual Life, tr. Mary Ryan (Westminster: The Newman Press, 1960), pp. xiii-xiv:

Are we perhaps ourselves exposed to the temptation of disparaging, envying, unjustly criticizing others, of disputing with them? We must then remember that such inclinations, which disturb and cause dissension, injure eternal truth and are incompatible with devotion to it.

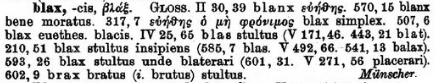

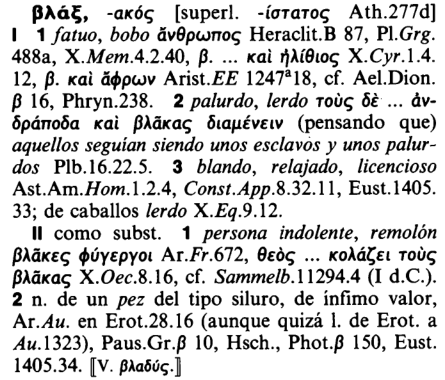

Blas and Blax

A.G. Rigg, ed., The Poems of Walter of Wimborne (Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 1978), p. 77 (De Mundi Vanitate, stanza 25, with the editor's note):

Ante litem enodeturMy translation:

iudicique demonstretur

pera feta cominus;

qui contendit sine pera

blas et bos est et chimera,

truncus, caper, asinus.

25/5 blas 'dolt'

Before trial let a full purse be untied and shown to the judge up close; he who goes to law without a purse is a dolt and an ox and a monster, a blockhead, a goat, an ass.Id., p. 328:

blas MV 25/5 fool (C, DC: Gr. βλάξ)Thesaurus Linguae Latinae, s.v. blax (2:2052): Diccionario Griego–Español, s.v. βλάξ (4:719):

Sunday, July 24, 2022

Memento Mori

Greek Anthology 11.38 (by King Polemo; tr. Charles Neaves, rev. Frederick Parkes Weber):

The poor man's armour see! this flask and bread,Greek dictionaries cite only this poem for ἀρτολάγυνος, so one might assume that it's a hapax legomenon, but cf. Thesaurus Linguae Latinae 2:710: D.R. Shackleton Bailey, ed., Cicero, Epistulae ad Familiares, vol. II: 47-43 B.C. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977; rpt. 2004), pp. 345 and 573: On the poem, see Évelyne Prioux, "Poetic Depictions of Ancient Dactyliothecae," in Maia Wellington Gahtan and Donatella Pegazzano, edd., Museum Archetypes and Collecting in the Ancient World (Leiden: Brill, 2015), pp. 54-71 (at 69-70), with the following illustration on p. 70:

This wreath of dewy leaves to deck the head;

This bone, too, of a dead man's brain the shell,

The soul's supreme and holy citadel.

The gem proclaims: 'Drink, eat, and twine your flowers;

This dead man's state will presently be ours.'

ἡ πτωχῶν χαρίεσσα πανοπλίη, ἀρτολάγυνος

αὕτη, καὶ δροσερῶν ἐκ πετάλων στέφανος,

καὶ τοῦτο φθιμένοιο προάστιον ἱερὸν ὀστεῦν

ἐγκεφάλου, ψυχῆς φρούριον ἀκρότατον.

πῖνε, λέγει τὸ γλύμμα, καὶ ἔσθιε καὶ περίκεισο 5

ἄνθεα· τοιοῦτοι γινόμεθ' ἐξαπίνης.

Imagine

Michael Warren Davis, The Reactionary Mind: Why "Conservative" Isn't Enough (Washington: Regnery Gateway, 2021), pp. 3-5:

Imagine a land where the average citizen lives on about twelve acres of land, and the poorest of the poor get by with just one. None of them have ever seen the road darkened by a skyscraper or heard the air split by the sound of a passing airplane. Nearly 100 percent of the population lives and works in the great outdoors. Their skin is a healthy bronze; their hands are strong and calloused; their muscles are hard, taut, and eminently practical, earned through long days of wholesome labor.

There are no pesticides or growth hormones in this country. All the meat and vegetables they eat are totally organic. Their furniture is what we would call antique, fashioned by master craftsmen in the local style and passed down from father to son over generations. To heat their homes, they burn wood in the fireplace. Of course, they chop the wood themselves.

Here, nothing is disposable—and nothing need be. When a man's trouser catches a nail, his wife can darn the tear in a matter of minutes. In fact, she herself made the trousers from wool her husband sheared from his own sheep. If a chair breaks, her husband fells a tree and carves a new one. Tinkering at these pleasant little chores under the shade of an oak tree might even be a definition of happiness.

For the most part, these folks walk everywhere they need to go. It keeps them fit and limber. Besides, they're never far from town: everything they need is, at most, a few miles from the front door. Not one of them has ever seen a throughway or a byway, and no tractor trailer has ever disturbed the quiet of this little domain. The only sounds a man hears are the whistle of the scythe as his son mows the barley, the low of the heifer as she brushes away flies with her tail, and the voice of his wife calling him in for lunch.

Of course, the routine changes slightly as the year goes on. Life here is tied to the seasons.

In spring, the men stay up all night drinking craft beer, roasting pigs and lambs for the Easter feast. This they'll eat with apples and plums and wild strawberries. The boys will crown the girls with garlands of wildflowers and woo them with memorized poetry. Broods of children will chase rabbits through the briar. Someone will play the guitar and the people will dance.

Come autumn, the men will hunt deer and geese. The harvest feast will be marked with hearty vegetable stews, tart cider or warm brandy, and all sorts of homemade cheeses. The men will build a great bonfire; the people will sing and dance; and when the celebration ends, families will walk home to their cottages. There's perfect silence over the valley. An owl hoots somewhere deep in the forest; a badger chitters in the brush.

Here, there are no streetlamps or strip malls. Once the sun sets, all is dark. Every living thing looks up and sees the same pale moon looming amid a crowd of stars. The road ahead is lit by these heavenly bodies. How could it be otherwise?

Welcome to a day in the life of a serf.

That's a slightly romanticized view…but only slightly. Our view of the Middle Ages has been clouded by centuries of bad history piled on top of one another.

An Imperfection of the Human Mind

Salvian, On the Governance of God 1.10.46 (tr. Jeremiah F. O'Sullivan, with his note):

We praise more the things that are gone than those of the present; not that, if we had the opportunity to choose, we would prefer to possess them forever, but because it is a well known imperfection of the human mind to want what it has not. As the proverb says:27 'Another's goods please us, and ours please others more.'

27 Syrus v. 28 (ed. Ribbeck).

nos magis laudamus illa quae tunc fuerunt quam ista quae nunc sunt, non quia si eligendi facultas esset, semper habere illa mallemus, sed quia usitatum hoc humanae mentis est vitium, illa magis semper velle quae desunt...ut ille ait, aliena nobis, nostra plus aliis placent.

Saturday, July 23, 2022

Nunnation

Tom Shippey, The Road to Middle-Earth, rev. ed. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2003), pp. 272-274, with note on p. 376 (on Tolkien's Smith of Wootton Major):

There is furthermore one element which seems to me a clear case of Tolkienian private symbolism, and that is the name of Smith's main antagonist throughout the work, the rude and incompetent Master Cook, Nokes. As I have said repeatedly, Tolkien was for some time perhaps the one person in the world who knew most about names, especially English names, and was most deeply interested in them. He wrote about them, commented on them, brought them up in conversation. With all the names in the telephone book to draw on, Tolkien is unlikely to have picked out just one name without considering what it meant: and 'Nokes' contains two clues as to its meaning. One is reinforced by the names of Smith's wife and son and daughter, Nell and Nan and Ned, all of them marked by 'nunnation', the English habit of putting an 'n' in front of a word, and especially a name, which originally did not have one, like Eleanor and Ann and Edward.4 In Nokes's case one can go further and observe place-names, as for instance Noke — a town in Oxfordshire not far from Brill — whose name is known to have been derived from Old English æt þam ácum, 'at the oaks'. This became in Middle English *atten okes, and in Modern English, by mistake, 'at Noke' or 'at Nokes'. There is no doubt that Tolkien knew all this, for there is a character called 'old Noakes' in the Shire, and Tolkien commented on his name, giving very much the explanation above, in his 'Guide to the Names in The Lord of the Rings', written probably in the late 1950s. Tolkien there wrote off the meaning of 'Noakes' as 'unimportant', as indeed it is for The Lord of the Rings, but it would be entirely characteristic of him to remember an unimportant philological point and turn it into an important one later.

The second clue lies in the derivation from 'oak'. 'Oak' had a special meaning for Tolkien, pointed out by Christopher Tolkien in his footnote to Shadow, p. 145.† In his early career as Professor at the University of Leeds, Tolkien had devised a system of splitting the curriculum of English studies into two separate groups or 'schemes', the 'A-scheme' and the 'B-scheme'. The A-scheme was for students of literature, the B-scheme for the philologists. Tolkien clearly liked this system, and tried unsuccessfully to introduce it to Oxford in 1930 with similar nomenclature (see 'OES', p. 780). But in his private symbolism 'A' was represented by the Old English rune-name ác, 'oak', 'B' by Old English beorc, 'birch'. Oaks were critics and birches philologists, and Tolkien made the point perfectly clear in Songs for the Philologists, for which see below. As must surely be obvious from chapters 1 and 2 of this work, oaks were furthermore the enemy: the enemy of philology, the enemy of imagination, the enemy of dragons. I do not think that Tolkien could ever have forgotten this.

† As often, I am amazed that did not at first recognise this, for at the time of my first comments on Smith I was still holding Tolkien's former position at the University of Leeds, and was in charge of the B-scheme, still in existence (though now no more). The B = birch equation, however, was no longer current.

4 Compare 'the skin o' my nuncle Tim' in Sam's 'Rhyme of the Troll', LOTR, p. 201. Many years before Tolkien had noted 'naunt' for 'aunt' in Sir Gawain; and Haigh's Huddersfield glossary of 1928 (see above) showed that saying 'aunt' instead of 'nont' was considered affected by his older informants. As often, old English survived only as vulgar modern English.

Wicked

Plato, Phaedo 115e (tr. Reginald Hackforth):

Then turning to Crito, 'My best of friends,' he continued, 'I would assure you that misuse of language is not only distasteful in itself, but actually harmful to the soul.'πλημμελής = out of tune, off-key, hence inappropriate, harmful, outrageous, from πλήν + μέλος.

εὖ γὰρ ἴσθι, ἦ δ᾽ ὅς, ὦ ἄριστε Κρίτων, τὸ μὴ καλῶς λέγειν οὐ μόνον εἰς αὐτὸ τοῦτο πλημμελές, ἀλλὰ καὶ κακόν τι ἐμποιεῖ ταῖς ψυχαῖς.

The Israelites in the Wilderness

Salvian, On the Governance of God 1.9.43 (tr. Jeremiah F. O'Sullivan):

Consider that the men felt in no parts of their bodies the increases and decreases natural to human beings; their nails did not grow, their teeth did not decay, their hair remained at one length, their feet were not inflamed, their clothing was not torn, their shoes were not worn, and thus the dignity of the men was so conspicuous that it enhanced their mean garments.Amazing.

adde homines in nullis membrorum suorum partibus accessus et decessus humanorum corporum sentientes, ungues non auctos, dentes non imminutos, capillos semper aequales, non adtritos pedes, non scissas vestes, calciamenta non rupta, redundantem hominum honorem usque ad induviarum vilium dignitatem.

Friday, July 22, 2022

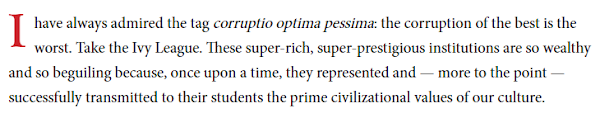

Corruption

Roger Kimball, "The Ivy League scolds come for Amy Wax," Spectator (July 20, 2022):

From Kenneth Haynes:

I have always admired the tag corruptio optima pessima: the corruption of the best is the worst.I don't admire a garbled Latin sentence. Read corruptio optimi pessima. Screen capture taken today: You can find hundreds of Google hits for Kimball's version, as well as many occurrences in books, but it's still wrong. On the proverb see Renzo Tosi, Dictionnaire des sentences latines et grecques, tr. Rebecca Lenoir (Grenoble: Jérôme Millon, 2010), #11, pp. 52-53: Tosi's earliest citation is from 1722, but there are many earlier examples. The earliest I can find is Delle Relationi Vniversali di Giovanni Botero Benese. Terza Parte (Rome: Georgio Ferrari, 1595), p. 57.

From Kenneth Haynes:

The earliest occurrence I know of "corruptio optimi pessima" in the familiar proverbial form comes from Nicholas of Lyra's Postilla Moralis (1339) on I Kings 13 (to judge on the basis of an early printed text). Here is a snapshot from a Google Books copy said to be from 1478: Expanding abbreviations and adding punctuation, I think that would make it:Idem dicendum de prelato malo et multo plus, quia regit in spiritualibus, que temporalibus preferuntur; corruptio enim optimi pessima iudicatur.

"The same is said of an evil prelate and much more, since he rules in spiritual things, which surpass temporal things; for the corruption of the best is judged the worst."

Labels: typographical and other errors

Goodbye

Juvenal 3.21-30 (tr. Susanna Braund, with her notes):

It was here that Umbricius then spoke: "There's no room in Rome for respectable skills and no reward for hard work. Today my means are less than yesterday, and tomorrow will wear away a bit more from the little that's left. That's why I have resolved to head for the place where Daedalus stripped off his tired wings.8 While my white hair is still new, while my fresh old age still stands upright, while Lachesis9 still has something to spin, and while I can walk on my own two feet without the help of a stick in my hand, I must say goodbye to my fatherland. Let Artorius and Catulus10 live there. Let the men who turn black into white stay on..."I wish someone would compile a Repertory of Conjectures on Juvenal.

8 Cumae.

9 One of the three Fates.

10 Possibly upstarts of the Augustan-Tiberian period.

hic tunc Vmbricius 'quando artibus' inquit 'honestis

nullus in urbe locus, nulla emolumenta laborum,

res hodie minor est here quam fuit atque †eadem† cras

deteret exiguis aliquid, proponimus illuc

ire, fatigatas ubi Daedalus exuit alas, 25

dum nova canities, dum prima et recta senectus,

dum superest Lachesi quod torqueat et pedibus me

porto meis nullo dextram subeunte bacillo.

cedamus patria. vivant Artorius istic

et Catulus, maneant qui nigrum in candida vertunt...'

23 eadem codd.: itidem Damsté: ideo Buecheler: fames Herwerden

Some Opposites

Calvert Watkins, "Some Celtic Phrasal Echoes," in A.T.E. Matonis and Daniel F. Melia, edd.,

Celtic Language, Celtic Culture: A Festschrift for Eric P. Hamp (Van Nuys: Ford & Bailie, 1990), pp. 47-56, rpt. in his Selected Writings, ed. Lisi Oliver, Vol. II: Culture and Poetics (Innsbruck: Institut für Sprachwissenschaft der Universität Innsbruck, 1994 = Innsbrucker Beiträge zur Sprachwissenschaft, 80), pp. 741-750 (at 745):

In 1967, resuming an oral presentation of 1958, Reinhold Merkelbach demonstrated that the virtually identical oaths on two papyri of the first and third centuries C.E. (respectively, P[ubbl.] S[oc.] I[tal.] 1290 and 1162) represent the oath of the Isis mysteries. It begins with a dualistic litanyI don't have access to Pubblicazioni della Società italiana per la ricerca dei papiri greci e latini in Egitto, but I find the Greek in Albert Bernabé, ed., Poetae Epici Graeci: Testimonia et Fragmenta, Pars II: Orphicorum et Orphicis Similium Testimonia et Fragmenta, Fasciculus 2 (Munich: K.G. Saur, 2005), p. 197, fragment 621, lines 10-19 (here without dots beneath doubtful letters):I swear ([ὀμν]ύω) by the one who divided and separated earth from heaven, and darkness from light, and day from night, and sunrise from sunset, and life from death, and birth from corruption, and black from white, and dry from wet, and sea from land, and bitter from sweet, and flesh from spirit,and continues ἐπόμνυμαι δὲ καὶ οὓς π[ροσκυνῶ θ]εοὺς,and I swear by the gods whom I worship (that I will preserve and protect the mysteries vouchsafed to me).

[Ὀμν]ύω κατὰ τοῦ διχάσαντος κ[αὶ κρί-] 10The object of συντηρήσειν καὶ φυλάξειν appears in the similar opening of the fragment (Bernabé, p. 194, lines 6-7):

ναντος τὴν γῆν ἀπ' οὐρανοῦ κα[ὶ σκότος]

[ἀπὸ] φωτὸς καὶ ἡμέραν ἐκ νυ[κτὸς]

[καὶ ἀ]νατολὴν ἀπὸ δύσεως καὶ [ζωὴν]

[ἀπὸ] θανάτου καὶ γένεσιν ἀπ[ὸ φθορᾶς]

[καὶ μ]έλαν [ἀ]πὸ λευκρῦ καὶ ξηρὸ̣[ν ἀπὸ] 15

[ὑγρ]οῦ καὶ ἔν̣[υδ]ρον ἀπὸ χερσ[αίου καὶ]

[πικ]ρὸν ἀπὸ γλυκέως καὶ σάρκ[α ἀπὸ]

[ψυχ]ῆς, ἐπόμνυμαι δὲ καὶ οὓς π[ροσκυνῶ]

[θεο]ὺς συντηρήσειν καὶ φυλά[ξειν]

[τὰ παραδεδ]ομένα μοι μυστή-Related post: Opposites.

[ρια καὶ τιμήσειν τὸν] πατέρα Σαραπίωνα.

Thursday, July 21, 2022

Loss of Vigor

Greek Anthology 11.30 (by Philodemus), tr. Richard Thomas in "'Death', Doxography, and the 'Termerian Evil' (Philodemus, Epigr. 27 Page = A.P. 11.30)," Classical Quarterly 41 (1991) 130-137 (at 130):

I who in time past was good for five or nine times, now, Aphrodite, hardly manage once from early night to sunrise. The thing itself, already often only at half-strength, is gradually dying. That's the last straw. Old age, old age, what will you do later when you come to me, if even now I am as languid as this?In his Loeb Classical Library translation, W.R. Paton resorts to the decent obscurity of Latin for the first couplet:

ὁ πρὶν ἐγὼ καὶ πέντε καὶ ἐννέα, νῦν, Ἀφροδίτη,

ἓν μόλις ἐκ πρώτης νυκτὸς ἐς ἠέλιον.

οἴμοι καὶ τοῦτ' αὐτὸ κατὰ βραχύ, πολλάκι δ᾽ ἤδη

ἡμιθαλές, θνῄσκει· τοῦτο τὸ Τερμέριον.

ὦ γῆρας γῆρας, τί ποθ᾽ ὕστερον ἢν ἀφίκηαι 5

ποιήσεις, ὅτε νῦν ὧδε μαραίνομεθα;

3 οἴμοι καὶ τοῦτ' αὐτὸ Jacobs: οἴμοι καὶ τοῦτο P

4 ἡμιθαλές Page: ἡμιθανές P

Qui prius ego et quinque et novem fututiones agebam, nunc, O Venus, vix unam possum ab prima nocte ad solem. And alas, this thing (it has often been half-dead) is gradually dying outright. This is the calamity of Termerus2 that I suffer. Old age, old age, what shalt thou do later, if thou comest, since already I am thus languid?

2 A proverbial expression for an appropriate punishment. The robber Termerus used to kill his victims by butting them with his head, and Heracles broke his head.

Unwelcome Among the Dead

Juvenal 2.153-158 (tr. G.G. Ramsay):

But just imagine them to be true — what would Curius and the two Scipios think? or Fabricius and the spirit of Camillus? What would the legion that fought at the Cremera think, or the young manhood that fell at Cannae; what would all those gallant hearts feel when a shade of this sort came down to them from here? They would wish to be purified; if only sulphur and torches and damp laurel-branches were to be had. Such is the degradation to which we have come!In his translation of these lines Peter Green omits all the proper names:

sed tu vera puta: Curius quid sentit et ambo

Scipiadae, quid Fabricius manesque Camilli,

quid Cremerae legio et Cannis consumpta iuventus, 155

tot bellorum animae, quotiens hinc talis ad illos

umbra venit? cuperent lustrari, si qua darentur

sulpura cum taedis et si foret umida laurus.

illic heu miseri traducimur.

159 illic PVGKLZ: illuc AHYU: istinc O

But just imagine it's true — how would our great dead captains

greet such a new arrival? And what about the flower

of our youth who died in battle, our slaughtered legionaries,

those myriad shades of war? If only they commanded

sulphur and torches in Hades, and a few damp laurel-twigs,

they’d insist on being purified. Yes: even among the dead

we're paraded to public scorn.

Wednesday, July 20, 2022

Degeneration

Juvenal 2.126-128 (tr. G.G. Ramsay):

O Father of our city,pater urbis = Romulus, Gradive = Mars.

whence came such wickedness among thy Latin shepherds?

How did such a lust possess thy grandchildren, O Gradivus?

o pater urbis,

unde nefas tantum Latiis pastoribus?

unde haec tetigit, Gradive, tuos urtica nepotes?

Advice to Cincius

Greek Anthology 11.28 (by Argentarius; tr. W.R. Paton):

Dead, five feet of earth shall be thine and thou shalt not look on the delightsThe same, tr. J.W. Mackail:

of life or on the rays of the sun.

So take the cup of unmixed wine and drain it rejoicing,

Cincius, with thy arm round thy lovely wife.

But if thou deemest wisdom to be immortal, know that Cleanthes

and Zeno went to deep Hades.

πέντε θανὼν κείσῃ κατέχων πόδας, οὐδὲ τὰ τερπνὰ

ζωῆς, οὐδ᾽ αὐγὰς ὄψεαι ἠελίου·

ὥστε λαβὼν Βάκχου ζωρὸν δέπας ἕλκε γεγηθώς,

Κίγκιε, καλλίστην ἀγκὰς ἔχων ἄλοχον.

εἰ δέ σοι ἀθανάτου σοφίης νόος, ἴσθι Κλεάνθης 5

καὶ Ζήνων ἀίδην τὸν βαθὺν ὡς ἔμολον.

Five feet shalt thou possess as thou liest dead, nor shalt see the pleasant things of life nor the beams of the sun; then joyfully lift and drain the unmixed cup of wine, O Cincius, holding a lovely wife in thine arm; and if philosophy say that thy mind is immortal, know that Cleanthes and Zeno went down to deep Hades.

In the Early Morning

Eduard Mörike (1804-1875), "In der Frühe," tr. David Luke:

No slumber soothes my burning eyes,

And at my window, in the skies,

The day's already bright.

Torn to and fro in its debates

My busy doubting mind creates

Dark phantoms of the night.

— Oh my soul, now cease

This self-torment, be at peace

And rejoice! now here, now there, the morning

Bells chime out, from their own sleep returning.

Kein Schlaf noch kühlt das Auge mir,

Dort gehet schon der Tag herfür

An meinem Kammerfenster.

Es wühlet mein verstörter Sinn

Noch zwischen Zweifeln her und hin

Und schaffet Nachtgespenster.

– Ängste, quäle

Dich nicht länger, meine Seele!

Freu dich! schon sind da und dorten

Morgenglocken wach geworden.

Tuesday, July 19, 2022

So Much the Better

Daniel Roche, The People of Paris: An Essay in Popular Culture in the 18th Century, tr. Marie Evans (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987), p. 201:

Sébastien Mercier saw everywhere valets who could read and erected this into a positive act of faith in the illuminating virtues of books: 'These days, you see a waiting-maid in her back-room, a lackey in an anteroom reading pamphlets. People can read in almost all classes of society — so much the better. They should read still more. A Nation that can read carries within it a particular and happy strength which can defy or confound despotism . . .'.13

13. L.-S. Mercier, La Tableau de Paris, vol. 9, p. 334.

Monday, July 18, 2022

Malice

Thomas Mann, The Magic Mountain, chapter 3 (tr. James E. Woods):

"Ha ha ha. What a sarcastic man you are, Herr Settembrini."

"Sarcastic? You mean malicious. Yes, I am a little malicious," Settembrini said. "My great worry is that I have been condemned to waste my malice on such miserable objects. I hope that you have nothing against malice, my good engineer. In my eyes it is the brightest sword that reason has against the powers of darkness and ugliness. Malice, sir, is the spirit of criticism, and criticism marks the origin of progress and enlightenment."

»Ha, ha, ha! Ich finde Sie aber spöttisch, Herr Settembrini.«

»Spöttisch? Sie meinen: boshaft. Ja, boshaft bin ich ein wenig —«, sagte Settembrini. »Mein Kummer ist, daß ich verurteilt bin, meine Bosheit an so elende Gegenstände zu verschwenden. Ich hoffe, Sie haben nichts gegen die Bosheit, Ingenieur! In meinen Augen ist sie die glänzendste Waffe der Vernunft gegen die Mächte der Finsternis und der Häßlichkeit. Bosheit, mein Herr, ist der Geist der Kritik, und Kritik bedeutet den Ursprung des Fortschrittes und der Aufklärung.«

Battle of the Teutoburg Forest

The Plague Will Spread

Juvenal 2.78-81 (tr. G.G. Ramsay):

This plague has come upon us by infection, and it will spread still further, just as in the fields the scab of one sheep, or the mange of one pig, destroys an entire herd; just as one bunch of grapes takes on its sickly colour from the aspect of its neighbour.Susanna Braund ad loc.:

dedit hanc contagio labem

et dabit in plures, sicut grex totus in agris

unius scabie cadit et porrigine porci 80

uvaque conspecta livorem ducit ab uva.

78 contagiŏ: of various sorts of infection or pollution, e.g. Plin. Ep. 10.96.9 superstitionis istius contagio; cf. Hor. Ep. 1.12.14 inter scabiem tantam et contagia lucri, Luc. 3.322 scelerum contagia. On the prosody see Introduction §8. labem 'stain', cf. Tac. Hist. 3.24 abolere labem prioris ignominiae.E. Courtney, "The Interpolations in Juvenal," Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies 22 (1975) 147-162 (at 158):

79 grex: a herd of any domesticated animals, here pigs (porci 80).

80 'dies because of the scab and mange of a single pig'. For the combination of scabies and porrigo cf. Lucil. 1115 W = 982 M corruptum scabie et porriginis plenum, of an old lion, and figuratively at Fronto 2 p. 112 (Haines) = 159 (van den Hout) scabies porrigo ex eiusmodi libris concipitur. Both words denote forms of eczema (itchy, blistering skin), cf. J. 8.34-5 canibus pigris scabieque uetusta leuibus. On the contagiousness of scabies see Otto scabies 1.

81 'the bunch of grapes takes on discoloration from the sight of another bunch', conspectā ... ab unā lit. 'from a bunch of grapes having been seen', J.'s (per)version of a proverb, uua uuam uidendo uaria fit (see Otto uua). For uua ... liuorem ducit cf. Virg. Ecl. 9.49 duceret ... uua colorem. liuor denotes a bluish colour generally caused by bruising, cf. J. 16.11 nigram infacie tumidis liuoribus offam and OLD 1, interpreting the present passage as 'a taint'. Although liuidus can be used to describe the normal process of grapes ripening (Hor. Od. 2.5.10 with Nisbet and Hubbard), the emphasis here is on disease.

The scholiast on 81 quotes a proverb uva uvam videndo varia fit, corresponding to the Greek βότρυς πρὸς βότρυν πεπαίνεται. This Greek proverb refers to envious emulation, which is not in point here; but this notion apparently suggested to Juvenal the word livor, which often indicates envy, but here refers to the colour of ripening grapes (so Prop. 4.2.13, Hor. Odes 2.5.9-12). Yet it is desirable for grapes to ripen, and I wonder if the line is spurious; Wirz, Philol. 37 (1877) 300 showed some uneasiness.Courtney refers to Hans Wirz, "Beiträge zur kritik und erklärung des Iuvenalis," Philologus 37 (1877) 293–301.

Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme!

Greek Anthology 11.25 (by Apollonides; tr. W.R. Paton):

After writing the above, I found J.W. Mackail's translation, in Select Epigrams from the Greek Anthology, 3rd ed. (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1911), p. 288:

Thou art asleep, my friend, but the cup itself is calling to thee:Paton's translation of μὴ τέρπου μοιριδίῃ μελέτῃ (line 2) doesn't seem quite right to me, nor does Hermann Beckby's "Reiß die Angst vor dem Tod dir aus dem Herzen!" Sleep is a rehearsal for death, and I would translate, "don't delight in this rehearsal of death," i.e. don't take pleasure in sleep. Cf. philosophy as μελέτη θανάτου (Plato, Phaedo 81a). Sleep and Death are brothers (Homer, Iliad 16.672, Hesiod, Theogony 756).

"Awake, and entertain not thyself with this meditation on death."

Spare not, Diodorus, but slipping greedily into wine,

drink it unmixed until thy knees give way.

The time shall come when we shall not drink—long, long time; but come, haste thee;

the age of wisdom is beginning to tint our temples.

ὑπνώεις, ὦ ᾿ταῖρε· τὸ δὲ σκύφος αὐτὸ βοᾷ σε·

ἔγρεο, μὴ τέρπου μοιριδίῃ μελέτῃ.

μὴ φείσῃ, Διόδωρε· λάβρος δ᾿ εἰς Βάκχον ὀλισθών,

ἄχρις ἐπὶ σφαλεροῦ ζωροπότει γόνατος.

ἔσσεθ᾿ ὅτ᾿ οὐ πιόμεσθα, πολὺς πολύς· ἀλλ᾿ ἄγ᾿ ἐπείγου· 5

ἡ συνετὴ κροτάφων ἅπτεται ἡμετέρων.

After writing the above, I found J.W. Mackail's translation, in Select Epigrams from the Greek Anthology, 3rd ed. (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1911), p. 288:

Thou slumberest, О comrade; but the cup itself cries to thee, ‘Awake; do not make thy pleasure in the rehearsal of death.' Spare not, Diodorus; slipping greedily into wine, drink deep, even to the tottering of the knee. Time shall be when we shall not drink, long and long; nay, come, make haste; prudence already lays her hand on our temples.

Sunday, July 17, 2022

One Road

Greek Anthology 11.23 (by Antipater of Sidon or Thessalonica; tr. W.R. Paton, with his note):

Men learned in the stars say I am short-lived.Robert A. Rohland, "Highway to Hell: AP 11.23 = Antipater of Thessalonica 38 G-P," Mnemosyne 72 (2019) 459-470 (at 460):

I am, Seleucus, but I care not.

There is one road down to Hades for all, and if mine is quicker,

I shall see Minos all the sooner.

Let us drink, for this is very truth, that wine is a horse for the road,

while foot-travellers take a by-path to Hades.3

3He will go by the royal road and mounted (on wine); the pedestrians are those who do not drink.

ὠκύμορόν με λέγουσι δαήμονες ἀνέρες ἄστρων·

εἰμὶ μέν, ἀλλ᾽ οὔ μοι τοῦτο, Σέλευκε, μέλει.

εἰς ἀίδην μία πᾶσι καταίβασις· εἰ δὲ ταχίων

ἡμετέρη, Μίνω θᾶσσον ἐποψόμεθα.

πίνωμεν καὶ δὴ γὰρ ἐτήτυμον, εἰς ὁδὸν ἵππος

οἶνος, ἐπεὶ πεζοῖς ἀτραπὸς εἰς ἀίδην.

This paper argues that the meaning of the last couplet becomes clearer, if it is understood as a playful allusion to a passage from Odyssey 11: as Antipater is faced with a prophecy to die young like Homer's Achilles, he looks for the one method that allows for the speediest and most sympotic katabasis in Homer and finds it in the wine-drinking of Odysseus' comrade Elpenor.

It's Hard

Juvenal 1.30 (tr. G.G. Ramsay):

It is hard not to write satire.Id. 1.79:

difficile est saturam non scribere.

Though nature say me nay, indignation will prompt my verse.Id. 1.87:

si natura negat, facit indignatio versum.

For when was Vice more rampant?Id. 1.147-149:

et quando uberior vitiorum copia?

To these ways of ours Posterity will have nothing to add; our grandchildren will do the same things, and desire the same things, that we do. All vice is at its acme.

nil erit ulterius, quod nostris moribus addat

posteritas: eadem facient cupientque minores.

omne in praecipiti vitium stetit.

Truth by Committee Vote

Theodore C. Blegen, The Kensington Rune Stone: New Light on an Old Riddle (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1968), p. 90:

Questions of history are not settled by juries or the votes of committees. They are not disposed of by resolutions of historical institutions. Sometimes they are not solved at all and continue to puzzle generation after generation. It may happen that new evidence or new discoveries on some disputed problems can add sources of knowledge not previously used. And it is possible that fresh analyses of old sources, made by newer scholarship with the aid of new evidence or altered perspectives, or both, may help to clarify questions that have defeated scholars in the past.

Saturday, July 16, 2022

Philology

Ludwig Traube (1861-1907), "Ein Nachruf auf Rudolf Schöll," Neue Jahrbücher für das klassische Altertum, Geschichte und Deutsche Literatur 19 (1907) 727-731 (at 728; tr. DeepL Translator):

My German is weak. I took two semesters of elementary German with Herr Hall at the University of Maine many years ago, and that is the extent of my formal instruction. I love the language, but I'm not very good at it. Anything I say about German should be taken with a grain of salt. Anything I say about anything should be taken with a grain of salt.

F.A. Wolf said that a good philologist must also have a pure character. Lachmann and Haupt were the strictest representatives of this ethical demand on themselves and others. Indeed, the many small things that the philologist, in order to get to the big picture, is forced to do every day, easily leads to pettiness, the quarrel about things easily leads to a quarrel about words, the power that man has or thinks he has over the dead letter easily leads to despotism and develops other ugly instincts. On the other hand, there is also a great moral power in philology. Among the sciences, it represents one of the purest strivings for truth for truth's sake; in itself there is no secondary purpose; it wants to understand and to advance to knowledge. Whether this knowledge can be put to practical use is of equal importance. We do not read Aristotle's Athenian state in order to be able to politicize and reform in our state. We are guided only by man's innate impulse to ask how things were, to separate the true from the false, appearance from reality.DeepL Translator did a good job here, but I'm not sure that "is of equal importance" gets the meaning of "gilt ihr gleich" quite right. Cf. gleichgültig. I might even go so far as to render it "is of little importance," or "is a matter of indifference."

F.A. Wolf sagte, ein guter Philolog müsse auch einen reinen Charakter haben. Lachmann und Haupt waren die strengsten Repräsentanten dieser ethischen Forderung an sich und andere. In der Tat führt das viele Kleine, das der Philologe, um zum großen Ganzen vorzudringen, täglich zu verrichten sich gezwungen sieht, leicht zum Kleinlichen, führt der Streit um Dinge leicht zum Streit um Worte, führt die Macht, die der Mensch dem toten Buchstaben gegenüber hat oder zu haben glaubt, leicht zum Despotismus und entwickelt andere häßliche Instinkte. Demgegenüber liegt aber auch eine große sittliche Kraft in der Philologie. Sie stellt in den Wissenschaften mit am reinsten das Streben nach Wahrheit um der Wahrheit willen dar; in ihr selbst liegt kein Nebenzweck, sie will verstehen und zur Erkenntnis vordringen. Ob diese Erkenntnis praktisch sich verwerten läßt, gilt ihr gleich. Wir lesen den Staat der Athener des Aristoteles nicht, um in unserem Staat politisieren und reformieren zu können. Uns leitet allein der dem Menschen eingeborene Trieb, zu fragen, wie die Dinge waren, das Wahre vom Falschen, den Schein von der Wirklichkeit zu scheiden.

My German is weak. I took two semesters of elementary German with Herr Hall at the University of Maine many years ago, and that is the extent of my formal instruction. I love the language, but I'm not very good at it. Anything I say about German should be taken with a grain of salt. Anything I say about anything should be taken with a grain of salt.

Progress and Politics

Gustave Flaubert (1821-1880), Bouvard and Pécuchet, chapter 6 (tr. anon.):

Bouvard mused: "Hey! progress! what humbug!" He added: "And politics, a nice heap of dirt!"

Bouvard songeait: «Hein, le Progrès, quelle blague!» Il ajouta: «Et la Politique, une belle saleté!»

Maternal Language

Einar Haugen (1906-1994), "The Mother Tongue," in Robert L. Cooper and Bernard J. Spolsky, edd., The Influence of Language on Culture and Thought: Essays in Honor of Joshua A. Fishman's Sixty-Fifth Birthday (Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 1991), pp. 75-84 (at 82):

In conclusion, I would suggest as a reasonable hypothesis that the term "mother tongue" has passed through three phases. In the early Middle Ages it was a primarily pejorative term to describe the unlearned language of women and children. It was in contrast with the "father's language" which was Latin. We cannot be sure whether it arose in Latin or German, but its presence in the Romance languages suggests that it may have been Latin. There is no reason to place it farther back than 1100. It arose to describe the new contrast between men's and women's language.Haugen in the same article (p. 80) translates two stanzas from the poem "Muttersprache" (1814) by Max von Schenkendorf (1783-1817):

A second stage came with the Renaissance and the Reformation, when the mother tongue became also the language of God, speaking through the Bible. Thanks to Wycliffe in England and Luther in Germany and their Scandinavian followers, the mother tongue became a force to be reckoned with. But it remained to a great degree limited to the religious sphere.

Not until the Romantic eighteen hundreds did it become a concern of the heart that came home to every man and woman. After people like Dante, Shakespeare, and Holberg had created a public for the vulgari eloquentia, it became a point of honor to promote and care for the folk language in country after country. Then writers like Schenkendorf and Grundtvig could write lyrics to the mother tongue. Mother had been promoted from being a mere wet nurse to becoming the spokesman of God and finally a human being.

Oh mother tongue, oh mother sound,Related posts:

How blissful, how beloved:

The first word to me reechoed,

The first sweet word of love,

The first tune I ever babbled,

It rings forever in my ear.

Alas, how sad at heart am I

When I in foreign lands reside,

When in foreign tongues I speak,

Have to use the foreign words

That I can never really love,

That do not ever reach my heart!

Muttersprache, Mutterlaut,

wie so wonnesam, so traut!

Erstes Wort, das mir erschallet,

süßes, erstes Liebeswort,

erster Ton, den ich gelallet,

klingest ewig in mir fort.

Ach, wie trüb ist meinem Sinn,

wenn ich in der Fremde bin,

wenn ich fremde Zungen üben,

fremde Worte brauchen muß,

die ich nimmermehr kann lieben,

die nicht klingen als ein Gruß!

- The Sound of One's Mother-Tongue

- Forsaking One's Native Language

- The Mother Tongue

- Muttersprache

- Our National Language

- We are Born Inside a Language

Friday, July 15, 2022

Conversation

Greek Anthology 7.33 (by Julian, Prefect of Egypt; tr. W.R. Paton):

A. "You died of drinking too much, Anacreon." B. "Yes, but I enjoyed it,

and you who do not drink will come to Hades, too."

α. πολλὰ πιὼν τέθνηκας, Ἀνάκρεον. β. ἀλλὰ τρυφήσας·

καὶ σὺ δὲ μὴ πίνων ἵξεαι εἰς Ἀΐδην.

The Memory of the Age That Is Gone

J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings, Part 3: The Return of the King (VI.9: The Grey Havens):

[Y]ou will read things out of the Red Book, and keep alive the memory of the age that is gone, so that people will remember the Great Danger and so love their beloved land all the more.

Gold

Euripides, fragment 324 Kannicht (from Danaë; tr. Charles Burton Gulick):

O Gold, fairest gift welcomed by mortals! For neither a mother, nor children in the house, nor loved father can bring such delights as thou and they that own thee in their halls. If the glance which shines from Kypris' eyes is like thine, no wonder that countless loves attend her.Latin translation by Seneca, Letters to Lucilius 115.14:

ὦ χρυσέ, δεξίωμα κάλλιστον βροτοῖς,

ὡς οὔτε μήτηρ ἡδονὰς τοιάσδ᾽ ἔχει,

οὐ παῖδες ἐν δόμοισιν, οὐ φίλος πατήρ,

οἵας σὺ χοἰ σὲ δώμασιν κεκτημένοι.

εἰ δ᾽ ἡ Κύπρις τοιοῦτον ὀφθαλμοῖς ὁρᾷ,

οὐ θαῦμ᾽ Ἔρωτας μυρίους αὐτὴν ἔχειν.

pecunia ingens generis humani bonum,See Ioanna Karamanou, Euripides Danae and Dictys: Introduction, Text and Commentary (Munich: K.G. Saur, 2006), pp. 78-82.

cui non voluptas matris aut blandae potest

par esse prolis, non sacer meritis parens.

tam dulce siquid Veneris in vultu micat,

merito illa amores caelitum atque hominum movet.

5 amores Erasmus: mores codd.

Thursday, July 14, 2022

The Little Red Hen

Calvert Watkins (1933-2013), How to Kill a Dragon: Aspects of Indo-European Poetics (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), p. 91:

Consider from our own culture the tale beginning 'Once upon a time, long, long, ago, there lived in a house upon a hill a pig, a duck, a cat, and a little red hen...' The diction is formulaic, invariant, and the rhetoric and poetics of the prose narrative, its division into balanced cola, polished and precise. The genre, wisdom literature cast as beast fable, is far older than Aesop. I do not know how old 'The Little Red Hen' is, nor how long English speakers have been telling a tale to children in this form or something like it. But it is striking that the whole story does not seem to contain a single Romance or even Scandinavian loanword, nor a single Latin loanword with the exception of mill, which probably entered the language prior to the Anglo-Saxon migration from the Continent to Britain.I can't find a version matching Watkins'. Cf. St. Nicholas, Vol. 1, No. 11 (September, 1874), pp. 680-681 (paragraph divisions added):

About twenty-five years ago my mother told me the story of the little red hen. She told it often to me at that time; but I have never heard it since. So I shall try to tell it to you now from memory:

There was once a little red hen. She was scratching near the barn one day, when she found a grain of wheat. She said, "Who will plant this wheat?" The rat said, "I wont;" the cat said, "I wont;" the dog said, "I wont;" the duck said, "I wont;" and the pig said, "I wont." The little red hen said, "I will, then." So she planted the grain of wheat.

After the wheat grew up and was ripe, the little red hen said, "Who will reap this wheat?" The rat said, "I wont;" the cat said, "I wont;" the dog said, "I wont;" the duck said, "I wont;" and the pig said, "I wont." The little red hen said, "I will, then." So she reaped the wheat.

Then she said, "Who will take this wheat to mill to be ground into flour?" The rat said, "I wont;" the cat said, "I wont;" the dog said, "I wont;" the duck said, "I wont:" and the pig said, "I wont." The little red hen said, "I will, then." So she took the wheat to mill.

When she came back with the flour, she said, "Who will make this into bread?" The rat said, "I wont;" the cat said, "I wont;" the dog said, "I wont;" the duck said, "I wont;" and the pig said, "I wont." The little red hen said, "I will, then." So she made it into bread.

Then she said, "Who will bake this bread?" The rat said, "I wont;" the cat said, "I wont;" the dog said, "I wont;" the duck said, "I wont;" and the pig said, "I wont." The little red hen said, "I will, then."

When the bread was baked, the little red hen said, "Who will EAT this bread?" The rat said, "I WILL;" the cat said, "I WILL;" the dog said, "I WILL;" the duck said, "I WILL;" and the pig said, "I WILL." The little red hen said, "No, you WONT, for I am going to do that myself." And she picked up the bread and ran off with it.

Work

Thomas Mann, The Magic Mountain, chapter 2 (tr. James E. Woods):

Newer› ‹Older

As things stood, work had to be regarded as unconditionally the most estimable thing in the world—ultimately there was nothing one could esteem more, it was the principle by which one stood or fell, the absolute of the age, the answer, so to speak, to its own question. His respect for work was, in its way, religious and, so far as he knew, unquestioning. But it was another matter to love it. And as much as he respected it, he could not love it—for one simple reason: it did not agree with him. The exertion of hard work was a strain on his nerves, tiring him quickly, and he quite candidly admitted that he much preferred his leisure—when time passed easily, unencumbered by the leaden weight of toil, and lay open before you, instead of being divided into a series of hurdles that you had to grit your teeth and take.

Wie alles lag, mußte sie ihm als das unbedingt Achtungswertste gelten, es gab im Grunde nichts Achtenswertes außer ihr, sie war das Prinzip, vor dem man bestand oder nicht bestand, das Absolutum der Zeit, sie beantwortete sozusagen sich selbst. Seine Achtung vor ihr war also religiöser und, soviel er wußte, unzweifelhafter Natur. Aber eine andere Frage war, ob er sie liebte; denn das konnte er nicht, so sehr er sie achtete, und zwar aus dem einfachen Grunde, weil sie ihm nicht bekam. An gestrengte Arbeit zerrte an seinen Nerven, sie erschöpfte ihn bald, und ganz offen gab er zu, daß er eigentlich viel mehr die freie Zeit liebe, die unbeschwerte, an der nicht die Bleigewichte der Mühsal hingen, die Zeit, die offen vor ihm gelegen hätte, nicht abgeteilt von zähneknirschend zu überwindenden Hindernissen.