Thursday, November 24, 2022

Portrait of an Intellectual

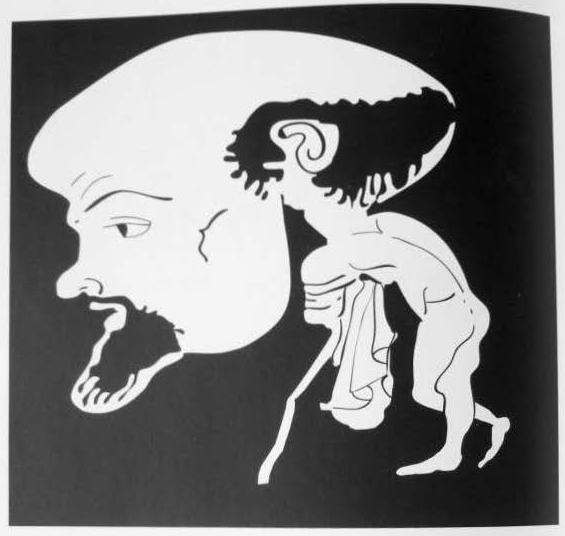

Red-figure askos (Paris, Louvre G 610):

Paul Zanker, The Mask of Socrates: The Image of the Intellectual in Antiquity, tr. Alan Shapiro (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995 = Sather Classical Lectures, 59), p. 33 (note omitted):

Newer› ‹Older

On a small red-figure askos, for example, of ca. 440 B.C., a naked, emaciated little man with an enormous head leans far forward on his slender staff and seems to be simply lost in contemplation. Just so, we are told, Socrates could stand still for hours, concentrating on a problem (fig. 20). The vase probably caricatures one of the leading thinkers of the day. The creature's bare skull, swelling out in all directions, seems about to burst with all the profound thoughts churning inside it. He is nevertheless an Athenian citizen, and not a member of one of those categories of inferiors like slaves or barbarians, as we can infer from the characteristic pose of resting on the staff and short mantle.Alexandre G. Mitchell, "Humour in Greek Vase-Painting," Revue Archéologique 37 (2004) 3-32 (at 18, notes omitted):

On one side a bald deformed man leans on a staff; the other side shows a roaring lion. The man’s body is absurdly small compared to his enormous head, larger than the whole body. He is leaning on a staff; his cloak is folded under his left arm and hangs off the staff. This bald man is strikingly caricatured. His attitude is that of many nonchalant strollers at the palaestra. With such a huge head and pensive attitude, this figure could be a caricature of a sophist; not a sophist in particular but what the common artisan in the Potters quarter thought of sophists, who spent their time thinking, or chatting at the palaestra. Views on sophists, or philosophers in antiquity were diverse. In Clouds Aristophanes gives a very critical and comical view of what was probably thought of intellectuals and "wandering wonder-workers" in Athens by most Athenians: "Bah! Good-for-nothings, I know. You're talking about those vagabonds, those pallid faces, those barefooted wanderers"; "lazy, supplied with food for doing nothing"; "who never went to the baths to wash". Socrates himself, in a discussion on the needs of the philosopher, clearly despises the body, while holds in the highest regard the soul. According to D. Metzler the lion is as symbol of hoplite virtue routing out the sophist parasite.There is a drawing of the intellectual based on this vase in Alexandre G. Mitchell, Greek Vase-Painting and the Origins of Visual Humour (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), p. 246, fig. 125: From Eric Thomson via email:

The egg-head's glabrous pate conforms in shape to the rounded convexity of the askos, and what does the banquet parasite do after a skinful but spout? The head is oriented in just that direction. The fact that the askos was originally a wine-skin is a bonus.