Thursday, July 31, 2025

Desire for Retirement

Thomas Jefferson, letter to James Madison (June 9, 1793):

There has been a time when these [sc. feelings] were very different from what they are now: when perhaps the esteem of the world was of higher value in my eye than every thing in it. But age, experience & reflection, preserving to that only it’s due value, have set a higher on tranquility. The motion of my blood no longer keeps time with the tumult of the world. It leads me to seek for happiness in the lap and love of my family, in the society of my neighbors & my books, in the wholesome occupations of my farm & my affairs, in an interest or affection in every bud that opens, in every breath that blows around me, in an entire freedom of rest or motion, of thought or incogitancy, owing account to myself alone of my hours & actions.

Sunday, July 27, 2025

Eternal War

Dio Cassius 38.39.2 (speech of Caesar; tr. Earnest Cary):

Against this prosperity many are plotting, since everything that lifts people above their fellows arouses both emulation and jealousy; and consequently an eternal warfare is waged by all inferiors against those who excel them in any way.

πολλοὶ γὰρ ἐπιβουλεύουσιν αὐτῇ· πᾶν γὰρ τὸ ὑπεραῖρόν τινας καὶ ζηλοῦται καὶ φθονεῖται, κἀκ τούτου πόλεμος ἀίδιός ἐστιν ἅπασι τοῖς καταδεεστέροις πρὸς τοὺς ἔν τινι αὐτῶν ὑπερέχοντας.

Thursday, July 24, 2025

A Foul-Tongued Man

Catullus 98 (tr. F.W. Cornish, rev. G.P. Goold):

You if any man, disgusting Victius, deserve what is said about chatterboxes and idiots. With a tongue like that, if need arose, you could lick arses and rustics' clogs. If you wish to destroy us all utterly, Victius, just open your mouth: you'll utterly do what you wish.In the spirit of Bowdler, F.W. Cornish left out "culos et" from his translation:

in te, si in quemquam, dici pote, putide Victi,

id quod verbosis dicitur et fatuis.

ista cum lingua, si usus veniat tibi, possis

culos et crepidas lingere carpatinas.

si nos omnino vis omnes perdere, Victi, 5

hiscas: omnino quod cupis efficies.

1, 5 Victi V: Vitti Haupt: Vetti Statius

6 hiscas Vossius: discas V; dehiscas Hendrickson

You if any man, disgusting Victius, deserve what is said about chatterboxes and idiots. With a tongue like that, given the chance you might lick a rustic's clogs. If you wish to destroy us all utterly, Victius, just utter a syllable: you'll utterly do what you wish.John Nott, The Poems of Caius Valerius Catullus, in English Verse, vol. II (London: J. Johnson, 1795), p. 155:

Foul-mouth'd Vectius! did any deserve the disdainRobinson Ellis ad loc.:

To conceit, and to talkative ignorance due,

'Tis thyself; whose rank tongue's only fit to lick clean

The most filthy of parts, or some hind's stinking shoe.

If thou'rt anxious to blast ev'ry friend thou mayst meet;

Do but open thy lips, and the wish is compleat!

It is doubtful to whom this epigram alludes. The MSS have Victi, one or two inferior ones Vitti: and this may represent the name Vettius, or Vectius. The history of Catullus' time contains one notorious person of this name, L. Vettius the informer, Vettius ille, ille noster index as he is called by Cicero Att. ii. 24. 2. His first appearance is in B.c. 62 when he accused J. Caesar of being an accomplice of Catiline, Suet. Iul. 17; later, in 59 B. c. he gave information to the younger Curio of a plot to assassinate Pompeius, was brought before the Senate and there produced a list of supposed conspirators, including Brutus and C. Bibulus the consul. This list he afterwards expanded, omitting Brutus and adding others not mentioned before, Lucullus, C. Fannius, L. Domitius, Cicero's son-in-law C. Piso, and M. Iuventius Laterensis. Cicero was not included; but was indicated as an eloquent consular who had said the occasion called for a Servilius Ahala or a Brutus. (Att. ii. 24, in Vatin. x, xi.) Vettius was not believed and was thrown into prison, where he was shortly afterwards found dead.

Cicero (in Vat. x. sqq.) asserts that Vettius was brought to the Rostra to make a public statement on this alleged conspiracy by Vatinius, and that as he was retiring he was recalled by Vatinius and asked whether he had any more names to add. An informer who did not scruple to charge some of the noblest and best men in Rome with so monstrous a design would naturally be hated, and this hatred would be increased by his connexion with Vatinius, the object of universal disgust. There is therefore nothing improbable in the view put forward doubtfully by Schwabe but accepted by Westphal, that the epigram of Catullus is directed against this L. Vettius. If the young Iuventius of the poems belonged to the family of Iuventius Laterensis, Catullus would have a personal motive in addition to public and general grounds of dislike: but public feeling alone would be enough to prompt the epigram. The persistency with which Cicero attaches the words index indicium to Vettius was doubtless meant to convey a slur; while the words of Catullus Ista cum lingua etc., find a practical commentary in Cicero's language ibi tu indicem Vettium linguam et uocem suam sceleri et menti tuae praebere uoluisti x. 24, just as Si nos omnino uis omnes perdere, Vetti is well illustrated by Cicero's ciuitatis lumina notasset xi. 26.

1. putide, 'disgusting,' XLII. 11.

2. fatuis, see on LXXXIII. 2. Fatui or idiots were sometimes kept in Roman houses Sen. Ep. 50. 1.

3. Ista cum lingua, 'as owner of that vile tongue,' Pers. iii. 1. 68 Cum hac dote poteris uel mendico nubere. Phorm. iii. 1. 1 Multimodis cum istoc animo es uituperandus. si usus ueniat tibi, 'should you ever have the opportunity,' Cato R. R. 157 Et hoc, si quando usus uenerit, qui debilis erit, haec res sanum facere potest. Mil. Glor. i. 1. 3 ubi usus ueniat.

4. Culos. Your tongue is so foul that it might well be employed as a peniculus for the filthiest purposes: either as a sponge to clean the posteriors (Paul. Diac. p. 208 M., Mart. xii. 48. 7) or a brush for removing the dirt from a rustic's shoe (Festus p. 230). carpatinas, or as it is sometimes spelt carbatinas, is explained by Hesych. μονόπελμον καὶ εὐτελὲς ὑπόδημα ἀγροικικόν, where Rich supposes μονόπελμον to mean having the sole and upper-leather all in one. Perhaps like the old English startup.

5. omnino omnes, Varro Bimarc. fr. ii Riese, 45 Bücheler Τρόπων τρόπους qui non modo ignorasse me Clamat, sed omnino omnis heroas negat Nescisse.

6. Hiscas, 'just speak.' Mayor on Phil. ii. 43. 111 Respondebisne ad haec aut omnino hiscere audebis? and cf. Sen. de vita beata 20 cited on CVIII. 3. omnino, 'by all means;' the two senses may be kept up by translating 'if you wish quite to kill all of us, just speak; you'll quite succeed in doing what you wish.' The word is perhaps taken from Vettius' speeches.

Labels: noctes scatologicae

The Romans

Josephus, Jewish War 3.72-75 (tr. H. St. J. Thackeray):

[72] For their nation does not wait for the outbreak of war to give men their first lesson in arms; they do not sit with folded hands in peace time only to put them in motion in the hour of need. On the contrary, as though they had been born with weapons in hand, they never have a truce from training, never wait for emergencies to arise. [73] Moreover, their peace manœuvres are no less strenuous than veritable warfare; each soldier daily throws all his energy into his drill, as though he were in action. [74] Hence that perfect ease with which they sustain the shock of battle: no confusion breaks their customary formation, no panic paralyses, no fatigue exhausts them; and as their opponents cannot match these qualities, victory is the invariable and certain consequence. [75] Indeed, it would not be wrong to describe their manœuvres as bloodless combats and their combats as sanguinary manœuvres.

[72] οὐ γὰρ αὐτοῖς ἀρχὴ τῶν ὅπλων ὁ πόλεμος, οὐδ᾿ ἐπὶ μόνας τὰς χρείας τὼ χεῖρε κινοῦσιν ἐν εἰρήνῃ προηργηκότες, ἀλλ᾿ ὥσπερ συμπεφυκότες τοῖς ὅπλοις οὐδέποτε τῆς ἀσκήσεως λαμβάνουσιν ἐκεχειρίαν οὐδὲ ἀναμένουσιν τοὺς καιρούς. [73] αἱ μελέται δ᾿ αὐτοῖς οὐδὲν τῆς κατὰ ἀλήθειαν εὐτονίας ἀποδέουσιν, ἀλλ᾿ ἕκαστος ὁσημέραι στρατιώτης πάσῃ προθυμίᾳ καθάπερ ἐν πολέμῳ γυμνάζεται. [74] διὸ κουφότατα τὰς μάχας διαφέρουσιν· οὔτε γὰρ ἀταξία διασκίδνησιν αὐτοὺς ἀπὸ τῆς ἐν ἔθει συντάξεως, οὔτε δέος ἐξίστησιν, οὔτε δαπανᾷ πόνος, ἕπεται δὲ τὸ κρατεῖν ἀεὶ κατὰ τῶν οὐχ ὁμοίων βέβαιον. [75] καὶ οὐκ ἂν ἁμάρτοι τις εἰπὼν τὰς μὲν μελέτας αὐτῶν χωρὶς αἵματος παρατάξεις, τὰς παρατάξεις δὲ μεθ᾿ αἵματος μελέτας.

Tuesday, July 22, 2025

A Dedicated Tutor

François Rabelais (1494-1553), Gargantua and Pantagruel I.23 (he = Gargantua, his tutor = Ponocrates; tr. J.M. Cohen):

Then he went into some private place to make excretion of his natural waste-products, and there his tutor repeated what had been read, explaining to him the more obscure and difficult points.

Puis il allait aux lieux secrets excréter le produit des digestions naturelles. Là, son précepteur répétait ce qu'on avait lu et lui expliquait les passages les plus obscurs et les plus difficiles.

Labels: noctes scatologicae

Mirth

Laurence Sterne (1713-1768), Tristram Shandy, Dedication to Mr. Pitt:

I live in a constant endeavour to fence against the infirmities of ill health, and other evils of life, by mirth; being firmly persuaded that every time a man smiles,—but much more so, when he laughs, it adds something to this Fragment of Life.

Monday, July 21, 2025

The Ritual of Greek Drinking

C.M. Bowra (1898-1971), Greek Lyric Poetry from Alcman to Simonides, 2nd rev. ed. (1961; rpt. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2000), p. 158 (Alcaeus, fragment 346; notes omitted):

πώνωμεν· τί τὰ λύχν᾿ ὀμμένομεν; δάκτυλος ἀμέρα.

κὰδ δἄερρε κυλίχναις μεγάλαις αἶψ' ἀπὺ πασσάλων.

οἶνον γὰρ Σεμέλας καὶ Δίος υἶος λαθικάδεον

ἀνθρώποισιν ἔδωκ᾿. ἔγχεε κέρναις ἔνα καὶ δύο

πλήαις κὰκ κεφάλας, <ἀ> δ᾿ ἀτέρα τὰν ἀτέραν κύλιξ

ὠθήτω.

Let us drink. Why do we wait for the lamps? The day has but an inch to go. Lift down the big cups at once from the pegs. For the son of Semele and Zeus gave wine to men to forget their cares. Mix one of water and two of wine, pour them in to the brim, and let one cup jostle another.

Here is the essential ritual of Greek drinking—the mention of the time of day, the drill of taking the cups from their pegs, the justification of wine because it gets rid of cares, the precise proportions of wine and water, and the call to keep the proceedings going by emptying thc cups quickly and calling for more. All is in order, but not quite usual. The drink is a good deal stronger than normally. When Alcaeus says ἔνα καὶ δύο he can only mean one part of water to two of wine, since in such phrases the water comes first and the wine second. This is evidently a special occasion when the wine is not only abundant but taken strong.

Saturday, July 19, 2025

Perjury

Erwin Rohde (1845-1898), Psyche, tr. W.B. Hillis (1925; rpt. Chicago: Ares Publishers, Inc., 1987), p. 54, n. 85:

It should be remembered also that no legal penalties against perjury existed in Greece, any more than in Rome. They were unnecessary in face of the general expectation that the deity whom the perjurer had invoked against himself would take immediate revenge upon the criminal.Related post: Offenses Against Gods.

Teetotallers

Caesar, Gallic War 4.2.6 (of the Suebi, a German tribe; tr. James J. O'Donnell):

They do not let wine be imported to them, for they think it softens men for hard work and makes them womanly.

vinum ad se omnino importari non sinunt, quod ea re ad laborem ferendum remollescere homines atque effeminari arbitrantur.

Thursday, July 17, 2025

Freeloader

Euripides, Rhesus 325-326 (tr. Richmond Lattimore):

He is here for the feasting, but he was not here

with spear in hand to help the huntsmen catch the game.

ἥκει γὰρ ἐς δαῖτ᾽, οὐ παρὼν κυνηγέταις

αἱροῦσι λείαν οὐδὲ συγκαμὼν δορί.

Wednesday, July 16, 2025

The Multitude

Euripides, Iphigenia at Aulis 1357 (tr. David Kovacs):

The multitude are a terrible bane.

τὸ πολὺ γὰρ δεινὸν κακόν.

Tuesday, July 15, 2025

An Evening's Entertainment

Xenophon, Anabasis 6.1.5-13 (tr. Robin Waterfield):

[5] They poured libations and sang a paean, and then two Thracians were the first to get to their feet. Still in their armour, they danced to the accompaniment of the pipes, lightly leaping high off the ground and thrusting with their swords. In the end one of them struck the other, and everyone thought the man had been wounded, though he fell in a somewhat contrived fashion. [6] The Paphlagonians shouted out loud at the sight. Then the first man stripped the other of his arms and armour and left, singing the Sitalces, while other Thracians carried the fallen man away as though he were dead, although in fact he was completely unscathed.

[7] Next, some Aenianians and Magnesians stood up and began a dance in armour called the karpaia, [8] which goes like this: one man puts down his weapons and starts to sow grain and drive a team, while constantly turning this way and that as though in fear; a robber approaches and the farmer spots him, grabs his weapons, goes to meet him, and fights him to stop him stealing his team of oxen. They keep time throughout with the music of the pipes. In the end the robber ties up the farmer and steals the oxen, but sometimes the farmer ties up the robber and then puts him under the yoke next to the oxen with his hands tied behind his back and drives him on.

[9] Next, a Mysian stepped forward with a light shield in each hand. As he danced, sometimes he pretended that he was fending off two opponents, but at other times he wielded both shields as though he were fighting just one man. Then he whirled and turned somersaults while keeping the shields in his hands, which made a beautiful display. [10] Finally, he performed the Persian dance, which involved clashing his shields together, while squatting and rising up again. He kept time throughout with the music of the pipes.

[11] After the Mysian it was the turn of the Mantineans to step forward, and others from elsewhere in Arcadia also got to their feet. Dressed in the most splendid armour they could muster, they paraded in time with a martial tune played on the pipes, chanted a paean, and performed the same dance they put on during their religious processions.

The Paphlagonians found it strange that all the dances they had seen involved armour, [12] and the Mysian, seeing how surprised they were, persuaded one of the Arcadians, who owned a dancing-girl, to let him dress her in the most beautiful costume he could find, give her a light shield, and then bring her on.

[13] She performed an elegant version of the Pyrrhic dance and received loud applause. The Paphlagonians asked whether the women fought alongside them, and the Greeks said that these were the very women who had put the king to flight from his camp. And so the evening came to an end.

[5] ἐπεὶ δὲ σπονδαί τε ἐγένοντο καὶ ἐπαιάνισαν, ἀνέστησαν πρῶτον μὲν Θρᾷκες καὶ πρὸς αὐλὸν ὠρχήσαντο σὺν τοῖς ὅπλοις καὶ ἥλλοντο ὑψηλά τε καὶ κούφως καὶ ταῖς μαχαίραις ἐχρῶντο· τέλος δὲ ὁ ἕτερος τὸν ἕτερον παίει, ὡς πᾶσιν ἐδόκει πεπληγέναι τὸν ἄνδρα· ὁ δ᾽ ἔπεσε τεχνικῶς πως. [6] καὶ ἀνέκραγον οἱ Παφλαγόνες. καὶ ὁ μὲν σκυλεύσας τὰ ὅπλα τοῦ ἑτέρου ἐξῄει ᾁδων τὸν Σιτάλκαν: ἄλλοι δὲ τῶν Θρᾳκῶν τὸν ἕτερον ἐξέφερον ὡς τεθνηκότα· ἦν δὲ οὐδὲν πεπονθώς.

[7] μετὰ τοῦτο Αἰνιᾶνες καὶ Μάγνητες ἀνέστησαν, οἳ ὠρχοῦντο τὴν καρπαίαν καλουμένην ἐν τοῖς ὅπλοις. [8] ὁ δὲ τρόπος τῆς ὀρχήσεως ἦν, ὁ μὲν παραθέμενος τὰ ὅπλα σπείρει καὶ ζευγηλατεῖ, πυκνὰ δὲ στρεφόμενος ὡς φοβούμενος, λῃστὴς δὲ προσέρχεται· ὁ δ᾽ ἐπειδὰν προΐδηται, ἀπαντᾷ ἁρπάσας τὰ ὅπλα καὶ μάχεται πρὸ τοῦ ζεύγους· καὶ οὗτοι ταῦτ᾽ ἐποίουν ἐν ῥυθμῷ πρὸς τὸν αὐλόν· καὶ τέλος ὁ λῃστὴς δήσας τὸν ἄνδρα καὶ τὸ ζεῦγος ἀπάγει·

[9] ἐνίοτε δὲ καὶ ὁ ζευγηλάτης τὸν λῃστήν: εἶτα παρὰ τοὺς βοῦς ζεύξας ὀπίσω τὼ χεῖρε δεδεμένον ἐλαύνει. μετὰ τοῦτο Μυσὸς εἰσῆλθεν ἐν ἑκατέρᾳ τῇ χειρὶ ἔχων πέλτην, καὶ τοτὲ μὲν ὡς δύο ἀντιταττομένων μιμούμενος ὠρχεῖτο, τοτὲ δὲ ὡς πρὸς ἕνα ἐχρῆτο ταῖς πέλταις, τοτὲ δ᾽ ἐδινεῖτο καὶ ἐξεκυβίστα ἔχων τὰς πέλτας, ὥστε ὄψιν καλὴν φαίνεσθαι. [10] τέλος δὲ τὸ περσικὸν ὠρχεῖτο κρούων τὰς πέλτας καὶ ὤκλαζε καὶ ἐξανίστατο· καὶ ταῦτα πάντα ἐν ῥυθμῷ ἐποίει πρὸς τὸν αὐλόν.

[11] ἐπὶ δὲ τούτῳ ἐπιόντες οἱ Μαντινεῖς καὶ ἄλλοι τινὲς τῶν Ἀρκάδων ἀναστάντες ἐξοπλισάμενοι ὡς ἐδύναντο κάλλιστα ᾖσάν τε ἐν ῥυθμῷ πρὸς τὸν ἐνόπλιον ῥυθμὸν αὐλούμενοι καὶ ἐπαιάνισαν καὶ ὠρχήσαντο ὥσπερ ἐν ταῖς πρὸς τοὺς θεοὺς προσόδοις.

ὁρῶντες δὲ οἱ Παφλαγόνες δεινὰ ἐποιοῦντο πάσας τὰς ὀρχήσεις ἐν ὅπλοις εἶναι. [12] ἐπὶ τούτοις ὁρῶν ὁ Μυσὸς ἐκπεπληγμένους αὐτούς, πείσας τῶν Ἀρκάδων τινὰ πεπαμένον ὀρχηστρίδα εἰσάγει σκευάσας ὡς ἐδύνατο κάλλιστα καὶ ἀσπίδα δοὺς κούφην αὐτῇ. ἡ δὲ ὠρχήσατο πυρρίχην ἐλαφρῶς.

[13] ἐνταῦθα κρότος ἦν πολύς, καὶ οἱ Παφλαγόνες ἤροντο εἰ καὶ γυναῖκες συνεμάχοντο αὐτοῖς. οἱ δ᾽ ἔλεγον ὅτι αὗται καὶ αἱ τρεψάμεναι εἶεν βασιλέα ἐκ τοῦ στρατοπέδου. τῇ μὲν νυκτὶ ταύτῃ τοῦτο τὸ τέλος ἐγένετο.

How to Live

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), Die fröhliche Wissenschaft, Book IV, § 338 (tr. Walter Kaufmann):

Live in seclusion so that you can live for yourself. Live in ignorance about what seems most important to your age. Between yourself and today lay the skin of at least three centuries. And the clamor of today, the noise of wars and revolutions should be a mere murmur for you.

Lebe im Verborgenen, damit du dir leben kannst! Lebe unwissend über Das, was deinem Zeitalter das Wichtigste dünkt! Lege zwischen dich und heute wenigstens die Haut von drei Jahrhunderten! Und das Geschrei von heute, der Lärm der Kriege und Revolutionen, soll dir ein Gemurmel sein!

Monday, July 14, 2025

Attacks on Citizenship Status

K.J. Dover (1920-2010), Greek Popular Morality in the Time of Plato and Aristotle (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1974; rpt. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 1994), p. 32:

The ingredients of these diatribes can be shown to be the common property of comedy and oratory.To the list add Akestor, nicknamed Sakas, from Aristophanes, Birds 30-35 (tr. Jeffrey Henderson):

(i) One or both of the opponent's parents are of foreign and/or servile birth, and he has improperly become an Athenian citizen.

So Aiskhines alleges (ii 78) that Demosthenes is 'descended on his mother's side from the nomad Scythians' or (iii 172) that he is 'on his mother's side a Greek-speaking Scythian barbarian' (ii 180). So does Deinarkhos i 14; cf. Lys. xxx 2 on Nikomakhos. Compare Kleon as a 'Paphlagonian' in Aristophanes' Knights, Kleophon as a 'Thracian' (Frogs 678ff., cf. Plato Comicus fr. 60), Hyperbolos as a 'Phrygian' (Polyzelos 5) or 'Lydian' (Plato Comicus fr. 170), and similar accusations of foreign birth against Lykon (Pherekrates fr. 11, Eupolis fr. 53), Arkhedemos (Eupolis fr. 71), Khaireas (Eupolis fr. 80) and Dieitrephes (Plato Comicus fr. 31); this list is only selective.

You see, gentlemen of the audience, we're sick with the opposite of Sacas' sickness: he's a non-citizen trying to force his way in, while we, being of good standing in tribe and clan, solid citizens, with no one trying to shoo us away, have up and left our country with both feet flying.Nan Dunbar on line 31 (student edition, pp. 116-117): D. Holwerda, ed., Scholia Vetera et Recentiora in Aristophanis Aves (Groningen: Egbert Forsten, 1991), p. 12:

ἡμεῖς γάρ, ὦνδρες οἱ παρόντες ἐν λόγῳ,

νόσον νοσοῦμεν τὴν ἐναντίαν Σάκᾳ·

ὁ μὲν γὰρ ὢν οὐκ ἀστὸς εἰσβιάζεται,

ἡμεῖς δὲ φυλῇ καὶ γένει τιμώμενοι,

ἀστοὶ μετ᾿ ἀστῶν, οὐ σοβοῦντος οὐδενὸς

ἀνεπτόμεθ᾿ ἐκ τῆς πατρίδος ἀμφοῖν τοῖν ποδοῖν.

Sunday, July 13, 2025

Mismatch Between Text and Translation

Caesar, The Gallic War. With an English Translation by H.J. Edwards (1917; rpt. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006 = Loeb Classical Library, 72), pp. 16-17 (1.11.4):

Eodem tempore [Aedui] Ambarri, necessarii et consanguinei Aeduorum, Caesarem certiorem faciunt sese depopulatis agris...In the Latin text Edwards indicated by square brackets that Aedui should be excised, but he included it in his translation. According to René Du Pontet's Oxford Classical Text edition, Bernhard Dinter proposed the excision, although the Budé and Teubner editions attribute the deletion to Alphonsus Ciacconius.

At the same time the Aedui Ambarri, close allies and kinsmen of the Aedui, informed Caesar that their lands had been laid waste...

Labels: typographical and other errors

The Illusion of Progress

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), The Will to Power, Book 1, § 90 (tr. Walter Kaufmann and R.J. Hollingdale):

Let us not be deceived! Time marches forward; we'd like to believe that everything that is in it also marches forward — that the development is one that moves forward.Related post: Progress.

The most level-headed are led astray by this illusion. But the nineteenth century does not represent progress over the sixteenth; and the German spirit of 1888 represents a regress from the German spirit of 1788.

Dass wir uns nicht täuschen! Die Zeit läuft vorwärts, wir möchten glauben, dass auch Alles, was in ihr ist, vorwärts läuft, — dass die Entwicklung eine Vorwärts-Entwicklung ist.

Das ist der Augenschein, von dem die Besonnensten verführt werden. Aber das neunzehnte Jahrhundert ist kein Fortschritt gegen das sechszehnte: und der deutsche Geist von 1888 ist ein Rückschritt gegen den deutschen Geist von 1788.

Saturday, July 12, 2025

Birds of a Feather

Liddell-Scott-Jones, s.v. ὁμόπτερος (9th ed., p. 1227):

A. of or with the same plumage, κίρκος A.Supp.224, cf. Pl.Phdr.256e; οἱ ἐμοὶ ὁ. my fellow-birds, birds of my feather, Ar.Av.229: then generally, comrades, fellows, Stratt.78. 2. metaph., of like feather, closely resembling, βόστρυχος ὁ. A.Ch.174, cf. E.El.530; νᾶες ὁ. consort-ships (or, as others, equally swift), A.Pers.559 (lyr., but λινόπτεροι is prob. cj.); ἀπήνα ὁ., i.e. the two brothers, Eteocles and Polynices, E.Ph.328(lyr.).

The Garrulous and the Reticent

Giacomo Leopardi (1798-1837), "Detti memorabili di Filippo Ottonieri," chap. 4, Operette Morali (tr. Giovanni Cecchetti):

Sometimes he said, smiling, that those people who are accustomed to communicating continuously their thoughts and their feelings to others will cry out even when they are alone if a fly bites them or if a flower vase overturns or if it slips from their hands whereas those who are used to living by themselves and to self-restraint will not utter a sound in the company of others, even if they have an apoplectic stroke.Related posts:

Diceva alle volte ridendo, che le persone assuefatte a comunicare di continuo cogli altri i propri pensieri e sentimenti, esclamano, anco essendo sole, se una mosca le morde, o che si versi loro un vaso, o fugga loro di mano; e che per lo contrario quelle che sono usate di vivere seco stesse e di contenersi nel proprio interno, se anco si sentono cogliere da un'apoplessia, trovandosi pure in presenza d'altri, non aprono bocca.

- Hide It in Darkness

- Letting It Out, versus Keeping It In

- It is Unmanly to Complain

- Complaining

- On Keeping a Stiff Upper Lip

- Grosse Seelen Dulden Still

- Hiding Troubles

- Nietzsche on Emotional Incontinence

- Buckled Lips

- Emotional Incontinence

- On Concealing One's Misfortunes

Sunday, July 06, 2025

Sourpuss

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), Die fröhliche Wissenschaft, Book III, § 239 (tr. Walter Kaufmann):

Joyless.— A single joyless person is enough to create constant discouragement and cloudy skies for a whole household. and it is a miracle if there is not one person like that. Happiness is not nearly so contagious a disease. Why?

Der Freudlose.— Ein einziger freudloser Mensch genügt schon, um einem ganzen Hausstande dauernden Missmuth und trüben Himmel zu machen; und nur durch ein Wunder geschieht es, dass dieser Eine fehlt!— Das Glück ist lange nicht eine so ansteckende Krankheit,—woher kommt das?

Saturday, July 05, 2025

Sickbed Reading

Gilbert Highet (1906-1978), Poets in a Landscape (1957; rpt. New York: New York Review Books, 2010), p. 86:

Sextus Propertius is one of the strangest of Latin poets. I remember that, when I was at college, I fell ill and was in hospital for many weeks. In order to keep my Latin from growing rusty, as soon as I began to be able to sit up and read, I asked my parents to send in a plain text of Propertius—the poems alone, without explanatory notes. I expected to read slowly and meditatively through it, without the interference of any editor, as one might read Keats or Lamartine.Id., p. 88:

Lying in the hospital, between the daily clinical tests and the visits of the doctor and desultory games of chess with the patient in the next bed, I thought about Propertius's peculiar way of writing poetry, and read on slowly through his book, mystified in almost every poem by the jagged ideas and obscure references which nevertheless seemed to accompany genuine experience and intense emotion. No other Latin poet I had ever read had prepared me for this cabalistic type of poetry. His emotions were strange enough—in particular, his blend of strong sexual passion with something like puritanism. His style was bold, elliptical, uncom-promising, intended for a small intelligentsia. But the most difficult thing to understand, even to sympathize with, was his habit of breaking suddenly away from violent personal emotion and introducing a remote Greek myth, not even as an interesting tale to be told, but as a decoration, which every reader was apparently expected to understand and appreciate.

We're the Greatest

Giacomo Leopardi (1798-1837), Zibaldone, tr. Kathleen Baldwin et al. (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013), p. 1773 (Z 4120-4121):

Not only, as I said elsewhere [→Z 646], did any barbarous century think themselves to be so, but every century thought and thinks it is the non plus ultra as far as the progress of the human mind is concerned, and that it is hard and nearly impossible for future centuries, certainly not past ones, to surpass it in knowledge of things, discoveries, etc., and especially in civilization....Likewise there is no nation or small community so barbarous or savage that [4121] it does not think it is first among nations, and its state, the most perfect, civilized, happy, and that that of all the other nations is worse the more it is different from its own. See Robertson, Storia d’America, Venice 1794, tome 2, pp. 126, 232-33. Likewise nations half or imperfectly civilized, even in Europe, etc. And it was ever thus.From Eric Thomson:

Non solo, come ho detto altrove, nessun secolo barbaro si credette esser tale, ma ogni secolo si credette e si crede essere il non plus ultra dei progressi dello spirito umano, e che le sue cognizioni, scoperte ec. e massime la sua civilizzazione difficilmente o in niun modo possano essere superate dai posteri, certo non dai passati....Così non v’è nazione nè popoletto così barbaro e selvaggio che [4121] non si creda la prima delle nazioni, e il suo stato, il più perfetto, civile, felice, e quel delle altre tanto peggiore quanto più diverso dal proprio. V. Robertson Stor. d’America, Venez. 1794. t.2. p. 116. 232-33. Così le nazioni mezzo civili, o imperfette, anche in Europa ec. E così sempre fu.

‘Any’ in ‘any barbarous century’ belongs to the class of NPIs (negatively oriented polarity-senstive items) but is inappropriate in this context. The translators seem to have fallen into the trap of hypercorrect avoidance of what seems on the surface multiple negation but isn't. 'Not only' affects the proposition "No barbarous century thinks themselves (sic) to be so” only as far as subject-verb inversion is concerned. The absolute negator 'no' is required, just as in 'Not only is no man an island …’ (Not only is *any* man an island’). End of quibble. Zibaldone is full of quibbles.

Friday, July 04, 2025

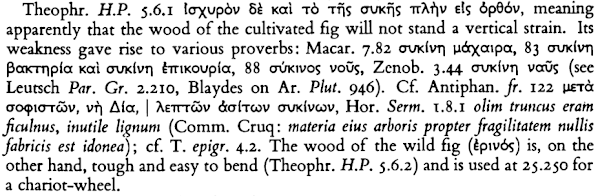

Inutile Lignum

Jeffery Henderson on Aristophanes, Lysistrata 110 (σκυτίνη ᾽πικουρία):

A play on the proverbial expression συκίνη ἐπικουρία, used of inadequate or unreliable help (so Σ): fig-wood was cheap and fragile, cf. Theokr. 10.45 σύκινοι ἄνδρες, and compare Hdt. 6.108 (of military aid) ἐπικουρίη ψυχρή, 'cold comfort'.Arthur Palmer on Horace, Satires 1.8.1 (inutile lignum):

The wood of the fig-tree was considered useless, because it was easily broken (εὔκλαστον), Schol. on Theocr. 25.248, quoted by Schütz; hence the proverb συκίνη ἐπικουρία = 'a broken reed': so σύκινοι ἄνδρες, Theocr. 10.45, 'good-for-nothing men': γνώμη συκίνη, Luc. adv. Indoct. 6.A.F.S. Gow on Theocritus 10.45 (σύκινοι ἄνδρες):

Companions

Theognis 115-116 (tr. J.M. Edmonds):

Many, for sure, are cup-and-trencher friends,T. Hudson-Williams ad loc.:

but few a man's comrades in a grave matter.

πολλοί τοι πόσιος καὶ βρώσιός εἰσιν ἑταῖροι,

ἐν δὲ σπουδαίωι πρήγματι παυρότεροι.

Religion

Christopher Marlowe (1564-1593), The Jew of Malta, Prologue 14-15 (spoken by Machiavel):

I count religion but a childish toy,

And hold there is no sin but ignorance.

Thursday, July 03, 2025

A Waste of Time

Walter Savage Landor (1775-1864), "Pericles and Aspasia," CIV, Imaginary Conversations:

What a deal of time we lose in business!

Wednesday, July 02, 2025

A Missing Modifier

Euripides, Helen, Phoenician Women, Orestes. Edited and Translated by David Kovacs (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002 = Loeb Classical Library, 11), pp. 396-397 (Phoenician Women 1764-1766):

Newer› ‹Older

ὦ μέγα σεμνὴ Νίκη, τὸν ἐμὸνThe translation omits μέγα σεμνὴ (greatly revered), modifying Νίκη (Victory). The same lines occur at the end of Euripides' Iphigenia Among the Taurians (1497-1499) and Orestes (1691-1693). Kovacs includes the modifier in his translation of Iphigenia Among the Taurians:

βίοτον κατέχοις

καὶ μὴ λήγοις στεφανοῦσα.

Victory, may you have my life in your charge and never cease garlanding my head!

O most august lady Victory, may you have my life in your charge and never cease garlanding my head!